New Ways to Use Less Energy at Home Concrete countertops

advertisement

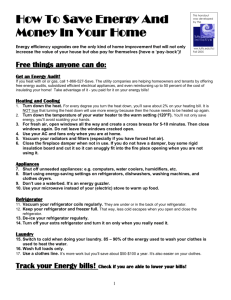

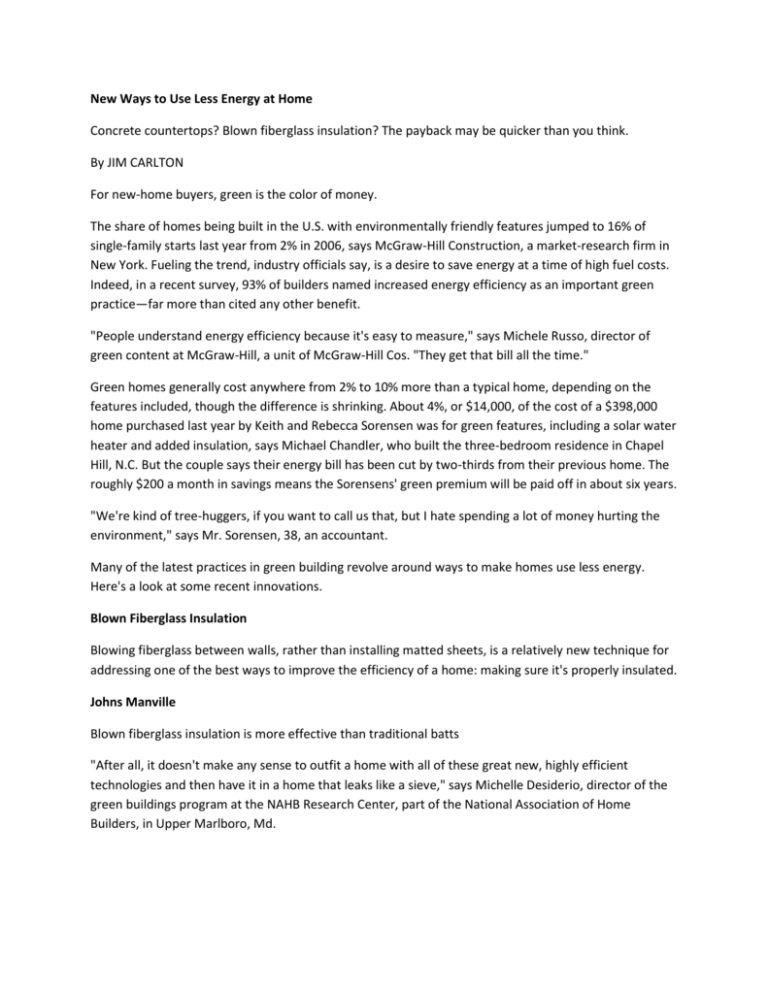

New Ways to Use Less Energy at Home Concrete countertops? Blown fiberglass insulation? The payback may be quicker than you think. By JIM CARLTON For new-home buyers, green is the color of money. The share of homes being built in the U.S. with environmentally friendly features jumped to 16% of single-family starts last year from 2% in 2006, says McGraw-Hill Construction, a market-research firm in New York. Fueling the trend, industry officials say, is a desire to save energy at a time of high fuel costs. Indeed, in a recent survey, 93% of builders named increased energy efficiency as an important green practice—far more than cited any other benefit. "People understand energy efficiency because it's easy to measure," says Michele Russo, director of green content at McGraw-Hill, a unit of McGraw-Hill Cos. "They get that bill all the time." Green homes generally cost anywhere from 2% to 10% more than a typical home, depending on the features included, though the difference is shrinking. About 4%, or $14,000, of the cost of a $398,000 home purchased last year by Keith and Rebecca Sorensen was for green features, including a solar water heater and added insulation, says Michael Chandler, who built the three-bedroom residence in Chapel Hill, N.C. But the couple says their energy bill has been cut by two-thirds from their previous home. The roughly $200 a month in savings means the Sorensens' green premium will be paid off in about six years. "We're kind of tree-huggers, if you want to call us that, but I hate spending a lot of money hurting the environment," says Mr. Sorensen, 38, an accountant. Many of the latest practices in green building revolve around ways to make homes use less energy. Here's a look at some recent innovations. Blown Fiberglass Insulation Blowing fiberglass between walls, rather than installing matted sheets, is a relatively new technique for addressing one of the best ways to improve the efficiency of a home: making sure it's properly insulated. Johns Manville Blown fiberglass insulation is more effective than traditional batts "After all, it doesn't make any sense to outfit a home with all of these great new, highly efficient technologies and then have it in a home that leaks like a sieve," says Michelle Desiderio, director of the green buildings program at the NAHB Research Center, part of the National Association of Home Builders, in Upper Marlboro, Md. The old standard in walls was fiberglass sheets, or "batts," but they often didn't keep rooms sealed very tightly. That led to a slew of competing products in recent years, such as cellulose, or recycled paper, and polyurethane spray foam, which provide more insulation because they are blown in to fill all the nooks and crannies between walls, Ms. Desiderio says. The fiberglass industry has fought back with new products that have insulation values rivaling cellulose and spray foam, without the potentially harmful chemicals they may contain. (Officials of those latter two industries say that toxicity is an issue only when the materials are being installed, and that workers are instructed to wear appropriate safety equipment to avoid exposure.) One technique has been to design a system of blowing fiberglass into wall cavities, such as the JM Spider Custom Insulation System from Denver-based Johns-Manville Corp. Builders who have switched back to fiberglass say that while the blowing technique costs as much as 40% more than using the batts, it's up to 50% cheaper than using spray foam. Cellulose costs about the same as blown-in fiberglass, but unlike the Spider fiberglass it can hold moisture, says Stephen Crouch, a residential market manager for Johns-Manville. Green-building experts say the higher insulation costs will eventually be offset by the home's overall energy savings, which can vary widely depending on what other green features are included. Mr. Crouch says Johns-Manville's Spider sales have continued to increase during the housing slowdown. Cellulose and spray foam have both continued to gain share in the home insulation market, say officials of the two industries. And cellulose has "superior" moisture-handling capabilities, says Daniel Lea, executive director of the Cellulose Insulation Manufacturers Association, in Dayton, Ohio. Mr. Lea adds that cellulose is the "greenest of green" insulation, in part because it has such a high content of recycled materials including newspapers. Spray foam, meanwhile, has added benefits such as being able to reinforce the structural integrity of a house, says Kurt Riesenberg, executive director of the Spray Polyurethane Foam Alliance in Fairfax, Va. Heat Pump Water Heaters Heat pump water heaters have hit the residential market over the past two years as a way to slash bills on electric water heating. Made by companies including General Electric Co. and Rheem Manufacturing Co., the water heaters suck heat out of the air such as in a garage or basement, like a refrigerator running in reverse, and use it to help heat water in a house. The savings can be significant: In the case of the Rheem HP-50 heat pump water heater, Rheem officials say the average annual operating cost of the device is between $225 and $280, or about half that of standard electric water heaters. But the heaters aren't cheap. They cost up to $1,500 for a 50-gallon model, or three times as much as a comparable conventional electric water heater and five times as much as natural-gas-powered units (though natural gas isn't available everywhere). To pay back the higher investment would take three to four years, based on the annual savings. Another issue with the heat pump units is that homeowners could inadvertently end up paying more to heat the home if one is installed in the wrong place. "If you put it in the garage, that's OK, but if you put one in your basement, that will pull heat out of the basement—forcing you to put more heat back in," says Joe Wiehgen, a senior research engineer at the NAHB Research Center. He suggested that wouldn't be as much of an issue in more temperate climes. Electronic Monitoring Several companies have come out with home monitoring systems over the past year that let homeowners track their energy use so they can turn off electricity where it isn't needed. In February, France's Schneider Electric SA introduced the Wiser Energy Management System, which lets homeowners see a computerized display of their power consumption so they can make adjustments, such as shutting down power to unused appliances. Costing about $600 with installation, the Wiser system can take $60, or 20%, off a $300-a-month power bill, meaning a payback period of as little as a year, says Jeff Drees, president of Schneider's U.S. division. Similarly, Newton, Mass.-based Powerhouse Dynamics Inc. last year introduced the eMonitor, which costs about the same and advertises a comparable payback period. At the Sorensen residence in North Carolina, the builder, Mr. Chandler, says he included an eMonitor system in the home and has agreed to monitor power use for the family. "It shows you in a graphical format where there are spikes and stuff," says Mr. Sorensen, who shares the home with his wife and their three children. Concrete Countertops At least one green building technology costs less right out of the gate: concrete countertops. Inspired by "Concrete Countertops: Design, Forms and Finishes for the New Kitchen and Bath," a book by designer Fu-Tung Cheng of Berkeley, Calif., builders around the U.S. have taken to making countertops by mixing their own concrete on a home site. The technique is considered both greener and cheaper because the concrete doesn't have to be shipped like the more prevalent granite counters, says Mr. Chandler, who began building them last year. According to online calculators, it costs around $1,100 to make 50 square feet of concrete countertop, compared with $2,000 for granite. But the do-it-yourself approach has its drawbacks. "The challenge is getting the right training for your crew," Mr. Chandler says. "You have to know how to reinforce steel in the right way. It's not intuitive." Mr. Carlton is a staff reporter in The Wall Street Journal's San Francisco bureau. He can be reached at jim.carlton@wsj.com.