Origins of Slavery Documents 9/16

advertisement

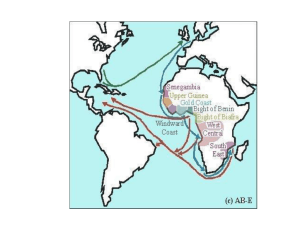

Origins of Slavery in colonial America Primary and Secondary Sources Source A (Primary): Excerpt from a Letter by John Rolfe of Jamestown, VA January 1620 About the latter end of August, a Dutch man of Warr* of the burden of a 160 tons arrived at Point-Comfort, the Commanders name Capt. Jope… He brought not anything but 20. And odd Negroes, which the Governor and Cape Marchant bought for victualle** (whereof he was in greate need as he portended) at the best and easiest rate they could. He had a lardge and ample Comyssion from his Excellency to range and to take purchase in the West Indyes. *A Man of War is a type of ship **Victuals means food or provisions Source B (Secondary): Life of Anthony Johnson In some ways he was a lucky man. To be sure, finding yourself in bondage on a Virginia tobacco plantation was not the result of good luck, but Anthony Johnson would rise above his low status and undoubtedly become the envy of many colonists. Anthony Johnson first arrived in Virginia in 1621. Referred to as "Antonio a Negro" in early records, Anthony went to work on a tobacco plantation. It's not clear whether he was an indentured servant (a servant contracted to work for a set amount of time) or a slave. Anthony nearly lost his life in the spring of 1622. Virginia's Powhatan Indians, threatened by the encroachments of tobacco planters, staged a carefully-planned attack that took place on Good Friday. By the middle of the day, over three hundred and fifty colonists were dead. On the plantation where Anthony worked, fifty-two were killed. Only Anthony and four other men survived. Anthony's luck continued. Several years later, "Mary a Negro" was brought in to work on the plantation -- she was the only woman on the plantation. At the time, Virginia was populated almost exclusively by men. Still, Anthony and Mary became husband and wife, and they had four children. Anthony and Mary eventually bought their way out of bondage. They acquired their own land. During the 1640s Anthony and Mary lived at their own place, raising livestock. By the 1650s, their estate had grown to 250 acres. For any ex-servant -black or white -- to own his own land was uncommon, despite the promise made by the Virginia Company to give a tract of land to each servant at the end of service. For an ex-servant to own 250 acres was rarer still. In 1665 Anthony and his family sold their 250 acres and moved to Maryland, where they leased a 300-arce tract of land. Anthony died five years later, in the spring of 1670; Mary renegotiated the lease for another 99 years. That same year, a court back in Virginia ruled that, because "he was a Negro and by consequence an alien," the land owned by Johnson (in Virginia) rightfully belonged to the Crown. Anthony Johnson lived a long life when, in America, disease and violent death by cruel overseers and Indian attacks resulted in low life expectancies. Court records reveal that he had the respect of his community -- a respect that would be denied African Americans in the years to come. Source C (Primary): Punishment for Runaway Servants July 9, 1640 Whereas Hugh Gwyn hath by order from this Board Brought back from Maryland three servants formerly run away from the said Gwyn, the court doth therefore order that the said three servants shall receive the punishment of whipping and to have thirty stripes apiece one called Victor, a dutchman, the other a Scotchman called James Gregory, shall first serve out their times with their master according to their Indentures, and one whole year apiece after the time of their service is Expired. By their said Indentures in recompense of his Loss sustained by their absence and after that service to their said master is Expired to serve the colony for three whole years apiece, and that the third being a negro named John Punch shall serve his said master or his assigns for the time of his natural Life here or elsewhere. Source D (Secondary): Africans in Court There were no laws in early in 17th-century Virginia that defined the rights, or lack of rights, of blacks. Four cases that came before Virginia courts illustrate their flexibility in the early decades of the colony -- a flexibility that would disappear as the end of the century approached. . . • John Graweere Case: In 1641, John Graweere appeared before the court, asking for permission to buy the freedom of his child in order that he could raise the child as a Christian. Even though the child's mother was a slave, the court granted Graweere permission. • Elizabeth Key Case: The illegitimate daughter of an enslaved black mother and a free white settler father, Elizabeth Key spent the first five or six years of her life at home. Then in 1636, ownership of Elizabeth was transferred to another white settler, for whom she was required to serve for nine years before being released from bondage. At some point, ownership was transferred again, this time to a justice of the peace. When this owner died in 1655, Elizabeth, through her lawyer, petitioned the court, asking for her freedom; by this time she had already served 19 years. The court granted her her freedom. Unfortunately, the decision was appealed to a higher court. The court overturned the decision, ruling that Elizabeth was a slave. Elizabeth and her lawyer didn't stop there. They petitioned the General Assembly, which appointed a committee to look into the matter. The committee sent the case back to the courts for retrial. Elizabeth was ultimately freed. Source E (Primary): Virginia Hereditary Bondage Laws December 1662 Whereas some doubts have arisen whether children got by any Englishman upon a Negro woman should be slave or free, be it therefore enacted and declared by this present Grand Assembly, that all children born in this country shall be held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother; and that if any Christian shall commit fornication with a Negro man or woman, he or she so offending shall pay double the fines imposed by the former act. September 1667 Whereas some doubts have risen whether children that are slaves by birth, and by the charity and piety of their owners made partakers of the blessed sacrament of baptism, should by virtue of their baptism be made free, it is enacted and declared by this Grand Assembly, and the auhority thereof, that the conferring of baptism does not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedom; that diverse masters, freed from this doubt may more carefully endeavor the propagation of Christianity by permitting children, though slaves, or chose of greater growth if capable, to be admitted to that sacrament. Source F (Secondary): Virginia’s Slave Codes The status of blacks in Virginia slowly changed over the last half of the 17th century. The black indentured servant, with his hope of freedom, was increasingly being replaced by the black slave. In 1705, the Virginia General Assembly removed any lingering uncertainty about this terrible transformation; it made a declaration that would seal the fate of African Americans for generations to come... "All servants imported and brought into the Country...who were not Christians in their native Country...shall be accounted and be slaves. All Negro, mulatto and Indian slaves within this dominion...shall be held to be real estate. If any slave resist his master...correcting such slave, and shall happen to be killed in such correction...the master shall be free of all punishment...as if such accident never happened." The code, which would also serve as a model for other colonies, went even further. The law imposed harsh physical punishments, since enslaved persons who did not own property could not be required to pay fines. It stated that slaves needed written permission to leave their plantation, that slaves found guilty of murder or rape would be hanged, that for robbing or any other major offence, the slave would receive sixty lashes and be placed in stocks, where his or her ears would be cut off, and that for minor offences, such as associating with whites, slaves would be whipped, branded, or maimed. For the 17th century slave in Virginia, disputes with a master could be brought before a court for judgement. With the slave codes of 1705, this no longer was the case. A slave owner who sought to break the most rebellious of slaves could now do so, knowing any punishment he inflicted, including death, would not result in even the slightest reprimand.