Outcome of discussions

advertisement

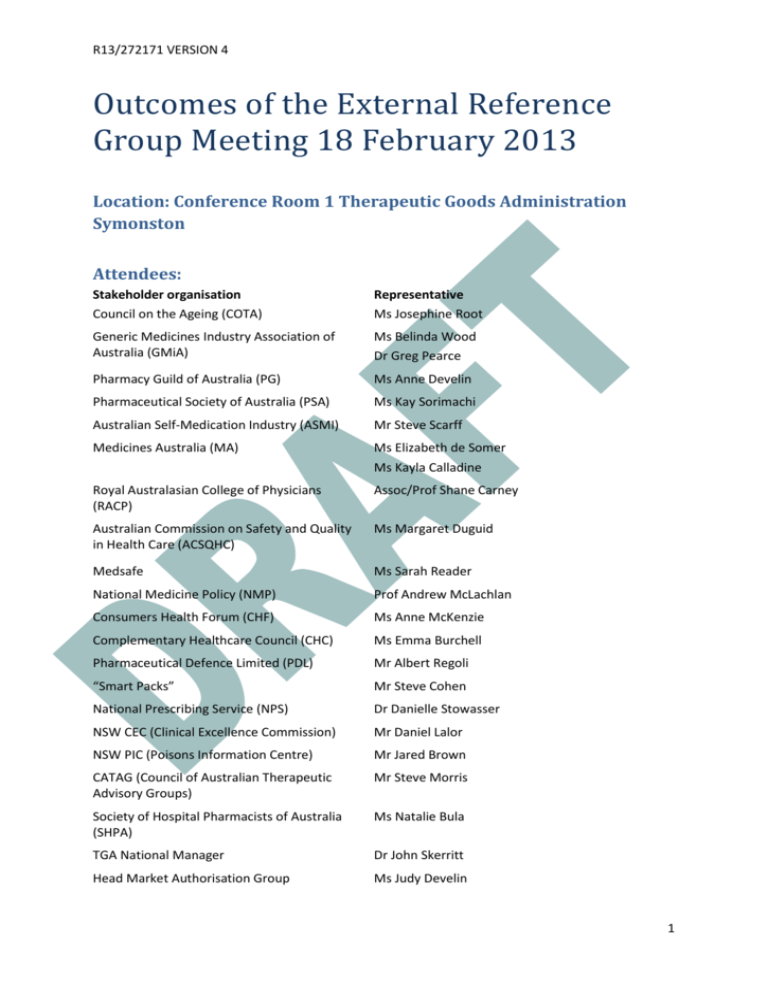

R13/272171 VERSION 4 Outcomes of the External Reference Group Meeting 18 February 2013 Location: Conference Room 1 Therapeutic Goods Administration Symonston Attendees: Stakeholder organisation Council on the Ageing (COTA) Representative Ms Josephine Root Generic Medicines Industry Association of Australia (GMiA) Ms Belinda Wood Dr Greg Pearce Pharmacy Guild of Australia (PG) Ms Anne Develin Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA) Ms Kay Sorimachi Australian Self-Medication Industry (ASMI) Mr Steve Scarff Medicines Australia (MA) Ms Elizabeth de Somer Ms Kayla Calladine Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) Assoc/Prof Shane Carney Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) Ms Margaret Duguid Medsafe Ms Sarah Reader National Medicine Policy (NMP) Prof Andrew McLachlan Consumers Health Forum (CHF) Ms Anne McKenzie Complementary Healthcare Council (CHC) Ms Emma Burchell Pharmaceutical Defence Limited (PDL) Mr Albert Regoli “Smart Packs” Mr Steve Cohen National Prescribing Service (NPS) Dr Danielle Stowasser NSW CEC (Clinical Excellence Commission) Mr Daniel Lalor NSW PIC (Poisons Information Centre) Mr Jared Brown CATAG (Council of Australian Therapeutic Advisory Groups) Mr Steve Morris Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia (SHPA) Ms Natalie Bula TGA National Manager Dr John Skerritt Head Market Authorisation Group Ms Judy Develin 1 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Office head (Office of Medicines Authorisation) Dr Peter Bird Project Manager Ms Suzanne Swensson Meeting Facilitator (Chair) Emeritus Professor Lloyd Sansom Office Head (Office of Scientific Evaluation) Dr Mark McDonald Director Committee Support Unit (TGA) Ms Kylie Barsley Office Head ( Office of Complementary Medicines) Ms Trisha Garrett TGA Chief Medical Officer Dr Anthony Hobbs DoHA Assistant Secretary Pharmaceutical Policy Branch PBD Mr StephenWaldegrave (morning only) DoHA Director National medicines Policy Mr Adrian White (afternoon only) Background: The Labelling and Packaging review is primarily concerned with the presentation of the information on the medicine containers or on the boxes within which they are supplied. Of particular interest are the visual aspects that contribute to the usability of the information provided and facilitate the safe use of the medicine by health care professionals and consumers. The key issues to be addressed by this review were determined through collation and analysis of previous consultations with key stakeholders on proposed updates to the legal instrument specifying labelling and packaging requirements for medicines in Australia, Therapeutics Goods Order 69 (TGO 69). The objective of the review of the requirements for medicine labels and packaging is to develop appropriate regulatory solutions that effectively address the consumer safety risks posed by the following issues: information about the active ingredient(s) contained in the medicine is not always easy to find; use of the same brand name for a range of products with different active ingredients resulting in look-alike medicine branding (this is known as brand extension or trade name extension); medicine names that look-alike and sound-alike that can lead to use of the incorrect medicine; medicine containers and packaging that looks like that of another medicine; lack of a standardised format for information included on medicines labels and packaging; dispensing stickers that cover up important information; information provided on blister strips; information included on small containers; information provided in pack inserts. 2 R13/272171 VERSION 4 However, it is recognised that any changes to be implemented must be affordable by industry and not undo positive aspects of product familiarity with names and packaging that patients have (i.e. association of product names with indications and packaging colours). For example, the trade name “Valium” has a long association with being a prescription anxiolytic and “Panadol”, with the accompanying green red and white packaging, an OTC analgesic. A consultation paper released in May 2012 sought comments on recommendations to change the presentation of information on the labels and packages of medicines. In response to the consultation, 110 submissions from interested stakeholders were received. The submissions were made by individual consumers, consumer representative groups, health care professionals and their organisations, academics and industry. An initial analysis identifying the key issues raised in the submissions as well as the proposed next steps was published on the TGA website. In January 2013, a document “Labelling and packaging practices: A summary of some of the evidence” was also published on the TGA website. As part of further consultation with stakeholders, a meeting of the External Reference Group was held on 18 February 2013 to discuss possible changes to the labelling and packaging for prescription and non-prescription (registered over-the-counter and registered complementary) medicines. An options paper was prepared which formed the basis of the discussion at the External Reference Group meeting. The options, presented below, were based on submissions to the Labelling and Packaging Review for the consultation process from May to August 2012. A summary of discussions and their outcomes is below. The discussion assisted in clarifying the views of the participants and the organisations they represented and in focussing options for further development from a list of alternatives down to two or three options. The next steps will be to work with relevant stakeholders to further fine tune options and undertake consumer testing of a limited number of shortlisted label options. Any cost impacts to industry would be taken into account when preparing the Regulation Impact Statement (RIS), which must be completed before any change can be implemented. Introduction: The Chair welcomed participants and opened the meeting by noting that labelling and packaging is primarily a quality use of medicines issue. He provided a summary to the background of the Labelling and Packaging Review (as above) and noted that there were two ways by which individual changes to labelling and packaging requirements could occur, the first by changes to the legislative basis of the Therapeutic Goods Order (TGO) and the second by industry participants using best practice guidelines that support the quality use of medicines. Key initial points made in the introduction included: Labelling and packaging of medicines can be improved, for the benefit of consumers and health professionals, in Australia. But it should also be noted that there are in the marketplace labelling and packaging examples that demonstrate good quality use of medicines principles. Labelling and packaging should be considered through the whole life cycle of the product, starting with being part of the drug development program of a company. For consumers, the 3 R13/272171 VERSION 4 point of sale, access and use in the home and, if required, appropriate disposal, are all important considerations. There is genuine concern from health professionals and consumers that without mandating particular requirements, avoidable medicines errors and challenges in identifying the substances involved in accidental poisonings and deliberate overdoses will continue to occur in Australia. International harmonisation should also be a consideration, including the upcoming formation of the Australia and New Zealand Therapeutic Products Agency (ANZTPA), when considering labelling and packaging issues. Labelling and packaging should not be considered in isolation as a tool for improving medicines safety. Consumer education is also very important and education programs should be provided to support any labelling and packaging changes to encourage quality use of medicines by consumers. Timeframes for implementation of any changes is noted to be an important issue for industry, with the need for significant periods to enable transition and avoid the need to discard current packaging inventory and to familiarise consumers with changes. Consumers must be central to the final agreed framework but it is recognised that the proposed solutions must be workable and be able to be implemented by industry in the context of their normal business cycles of refreshing product labels. At commencement of the meeting a letter was tabled from key organisations (including the Australasian Society of Clinical and Experimental Pharmacologists and Toxicologists (ASCEPT), Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA), Council of Australian Therapeutic Advisory groups (CATAG), Australian Pharmaceutical Science Association (APSA), Australian Medical Association (AMA), Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia (SHPA) and the Royal Australian College of Physicians (RACP)) indicating strong support and commitment to specific proposed labelling and packaging changes. This letter is at Attachment A. A. Active Ingredient Prominence – Prescription and non-prescription registered medicines Original options proposed 1. Introduce specific and mandatory requirements for display of active ingredient names A. Active ingredient name - font size and style The active ingredient MUST be presented as the same size as the brand name; or The active ingredient(s) MUST be presented in “due prominence” relative to the brand name, consistent with MHRA requirements in the UK1. This may be achieved by means including text size, colour, “white space”, bolding or contrasting font; 1 Best Practice Guidance on the Labelling and Packaging of Medicines, Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, May 2012 http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Howweregulate/Medicines/Labelspatientinformationleafletsandpackaging/Overview oflabelspatientinformationleafletsandpackagingformedicines/index.htm 4 R13/272171 VERSION 4 or The active ingredient must be displayed in font not less than 50% the size of the brand name with a minimum font size of 2 mm. B. Active ingredient – lettering case Active ingredient names should be presented in all lower case, consistent with the Australian Medicines Terminology (AMT) (Table 144: Appendix A - Capitalisation rules) but noting the need for use of capitalisation in Latin binomials when organisms are the active ingredient. Active ingredient names should be presented with similar prominence and contrast against the background as brand names. C. Active ingredient - location The active ingredient(s) is to appear in a standardised location on the main panel of a medicine label, immediately above the brand name; or The active ingredient(s) is to appear in a standardised location on the main panel of a medicine label, immediately below the brand name. Details regarding justification, font style and colour are at the sponsor’s discretion. Where space permits, the brand name and active ingredient(s) should appear on 3 nonopposing faces of a medicine box. Discussion The discussion applied to prescription and non-prescription registered medicines. Three issues were identified as problems with regards to the active ingredient: prominence, location and size. Consumers and health professional representatives proposed that the font size of the active ingredient for both prescription and non-prescription medicines should be at least the same font size as the brand name, particularly if there is one ingredient, and be in a standard location. The active ingredient and brand name should also be displayed on the packet on at least three non-opposing sides for prescription medicines but could remain as is for nonprescription medicines. Industry (ASMI) argued that “due prominence”, which is the MHRA requirement, was sufficient for non-prescription medicines, and that use of the same size lettering would decrease the importance of brand recognition and therapeutic indication, potentially creating confusion. Prescription and non-prescription medicines industry representatives considered that harmonisation with overseas jurisdictions to be important, as a large percentage of packages were manufactured overseas for the Australian market. It was noted that the MHRA UK Guidelines specified that the active ingredient should be given “due prominence” which would be generally determined by the relative size of the text but that other factors such as colour of text, the font used and other graphic elements 5 R13/272171 VERSION 4 on the pack would be considered. The MHRA UK Guidelines also specify that the information hierarchy is important and critical information should appear in the order stated. The current TGA guidelines also state that active ingredient should have “due prominence” but that this was often not adhered to by manufacturers. Examples of widely differing interpretation of “due prominence” were discussed. It was noted that the US FDA did prescribe a minimum font size for information on medicine labels, including active ingredient name. It was suggested by industry that mock ups of various size options for active ingredient/brand be tested although several participants indicated that there is already sufficient evidence in the literature and from clinical practice to support equal size for active ingredient/brand name, particularly for products with single ingredients. However, it was acknowledged that there may need for different requirements for medicines with multiple ingredients. A reduction in font size for each active ingredient for products with multiple ingredients may be needed if the total size of the active ingredient and brand name are required to be equal. In late 2012, TGA had undertaken to carry out targeted, independent label testing and discussion of the results with stakeholders prior to proposing specific label changes to government. It was noted that any changes should also be accompanied by education programs for consumers. Outcome of discussions For prescription and non-prescription medicines: The majority view was that any changes agreed to by government should be specified in the TGO, rather than as guidelines. The majority view was that for products containing a single ingredient, the brand name and the active ingredient must be at least equal in font size and prominence. The majority view but not unanimous was that for products containing two or three active ingredients the space shared by the active ingredients should be the same size as the brand name. The majority but not unanimous view was that these practices should apply for both prescription and registered over-the-counter (OTC) medicines. Several issues remain to be resolved: o Font styles for active ingredients in OTC non-prescription medicines should be in black sans serif font, lower case, consistent with Australian Medical Terminology (AMT) and consistent with the current TGA Best Practice Guideline on Prescription Medicine Labelling. o Font styles for trade names could incorporate colours and designs and not have limitations on font style of capitalisation, to provide continued brand recognition. o Achievement of equal prominence. For products containing more than three active ingredients, the current TGO requirements should apply i.e. the names can be included on a side or rear panel or side or rear label of the primary pack. 6 R13/272171 VERSION 4 There should be a consistent approach to the location of the active ingredient with respect to the brand name i.e. above or below the brand name. (The active ingredient name is currently placed under the brand name for prescription medicines). It was felt that a consistent approach should be applied to registered OTC medicines, with the active ingredient name appearing close to the trade name and in a consistent position. There was the need to determine the hierarchy for display of the information including symptoms/ indications for non-prescription medicines. It is recognised that the symptoms/indications was an important part of the process of consumer self-medication choice. Consumer testing will be required to assess the impact of these options. 2. Introduction of specific requirements for generic medicines Original options proposed New generic medicines be marketed only by the active ingredient, i.e. no brand name. Product differentiation will be achieved using the sponsor’s name. For example: “amoxycillin- Chemist Brand”; or Maintain the ability for brand names to be nominated by generic sponsors, but require that the sponsor name MUST NOT be included as a prefix before the active ingredient to create a brand name. (Rationale: Due to the use of drop down menus for electronic prescribing and the way medicines are stacked on pharmacists’ shelves, this practice creates a heightened risk of medicine confusion). Discussion The discussion applied only to prescription medicines. It was noted that the UK does not allow brand names for generic medicines. On the packaging, the active ingredient is followed by the strength then the manufacturer’s name. It was also noted that doctors prescribe generically in the UK. Generic medicines industry representatives requested that sponsors have the option of choosing a brand name. However it was acknowledged that choosing a brand name for generic products was sometimes difficult and was often rejected by the TGA because the name was considered inappropriate or unsuitable. Industry thought that in time the naming of generics may decrease due to this difficulty. Generic industry considered that by having the choice of brand name that this would allow a more level playing field for generic companies with innovator companies. There was discussion about removing the brand name of innovator medicines once a generic medicine became available, but this was not considered practical as both patients and doctors recognise their medicines by brand, and generic prescribing is not as widely embraced in Australia as it is in the UK, particularly in private GP practice. It was also noted by industry that sponsors of innovator medicines consider a brand name to be an important factor in product recognition and use, and that this was agreed by many at the meeting. 7 R13/272171 VERSION 4 There was also discussion about how the potential removal of brand names for generics would affect electronic prescribing and dispensing software and whether this may provide difficulties in choosing the right product and also create problems with respect to brand substitution. It was noted that some patients may be prescribed a particular brand of medicine (e.g. for the treatment of epilepsy), which may be either an innovator or generic medicine, and if there was no brand name, this may result in another brand being substituted, which might not be appropriate for some patients. The issue of placement of active ingredient either above or below the brand name was not a big issue for consumers, so long as placement was consistent. There was discussion whether the size of the lettering for the active ingredient should be larger than the brand name for generic medicines but the group considered that the preferred option should be that the active ingredient name be “at least” the same size as the brand name and specified as such in the TGO. There was general agreement that company acronyms such as prefixes and suffixes should not be used as it confuses patients and prescribers and may potentially cause errors when using electronic prescribing. However, this is integral to some generic companies’ long-established branding practices and further discussion may be required. It was noted that the UK had an accepted list of suffix abbreviations, such as those used for longer acting medications e.g. controlled release, sustained release, and the group considered that any list available in Australia should be consistent with international requirements. Outcome of discussions For prescription medicines only: Allow sponsors of generic products to propose brand names for their products. Move away from allowing prefixes and suffixes in the brand name that identify the company, noting further industry negotiation will be required here. The brand name, the active ingredient and strength must be at least equal in font size and prominence. The TGA to review the list of suffix abbreviations allowed to represent dose form (e.g. sustained release), taking into account international requirements for harmonisation. 3. Introduce specific requirements for Similar Biological Medicinal Products (SBMPSs also known as biosimilars) Original options proposed SBMPs should use only unique brand names and not names composed of active ingredient name and the sponsor name. (Rationale: Unlike small molecule generic medicines, SBMPs are not identical to the originator product at the molecular level). Use of unique brand names allows the tracing of these high risk medicines for adverse drug reactions. Active ingredient names must be registered with the Australian Biological Names Committee and comply with the naming convention set out in the draft Guideline for the Evaluation of Similar Biological Medicinal Products. 8 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Discussion The discussion applied only to prescription medicines. The group considered that the same requirement for the font size of active ingredient and brand name be applied to SMBPs i.e. the font size of the active ingredient be at least equal to the font size of the brand name and have the same prominence. The group noted that SMBPs are not considered to be interchangeable by regulators worldwide and are often identified by prescribers by their brand name. Outcome of discussion For prescription medicines only: The brand name and the active ingredient must be at least equal in font size and prominence. Brand names should consistently be used for similar biological medical products. Original option proposed 4. Retain the current requirements as set out in TGO 69 and the Best Practice Guideline for prescription medicine labelling. The TGO 69 mandates what should be specified on the main label and the Best Practice Guideline states that the active ingredients names and strength should be prominently and equally displayed on the packet on at least three sides, including two end panels. Outcome of discussions The group considered that this was not an option and recommended changes to the active ingredient size and prominence as outlined above which should be incorporated into the TGO, as well as recommending that the current TGA Best Practice Guideline for Prescription Medicine Labelling be updated in accordance with changes recommended for TGO 69. Other matters discussed: Is there a need to include complete details of the salt for an active ingredient or is it sufficient for this to be included in the CMI and PI? Or is there an internationally accepted and appropriate abbreviation style that can be adopted? Discussion The group discussed whether it is important to include the salt of the active ingredient on the packaging and noted an example where different salts of a medicine had different strengths but contained the same amount of base medicine e.g perindopril (perindopril arginine 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg/equivalent to perindopril erbumine 2 mg, 4 mg and 8 mg respectively). In this case, if the salt was not included in the active ingredient name the consumer might think that they had to take more of one (erbumine) to be equivalent to the other (arginine) salt. Therefore, in cases like this, it was considered that the salt should form part of the active ingredient name to avoid confusion. 9 R13/272171 VERSION 4 The group also noted that the way the AAN (Australian approved name) may be expressed differently on the label, i.e. including the salt in the active ingredient name or as expressed as the free base e.g. perindopril (base) (as arginine) Outcome of discussions The group noted that the TGA approved name includes the salt of the active ingredient and that including this in the name of the active ingredient would not be a hazard to consumers and may assist consumers in understanding differences between medications. Therefore, the TGO should be changed to specify that the active ingredient name should include the salt if relevant. How can requirements for active ingredients be accommodated on small containers or ampoules? Outcome of discussions The group considered that further discussion should take place with various health professional groups (such as The Pharmacy Guild, the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia and the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia) regarding the provision of consistent standards for the labelling of small containers so that significant information on prescription medicines in small containers is not covered when a dispensing label is applied. Should there be different requirements for specialised products, for example vaccines, or antivenoms? Outcome of discussions The group considered that the above principles should apply to specialised products such as vaccines or anti-venoms but noted that the sponsor can apply for an exemption where compliance with the TGO cannot be met. Should guidelines be developed for the use of colour to differentiate products or different doses in a sponsor’s range? Outcome of discussions The group considered that Guidelines similar to the National Patient Safety Agency’s “Guide to the Graphic Design of Medication Packaging” should be adopted or developed, particularly to clearly differentiate the numerous strengths of a medicine and that the differentiation of the strengths should be significant. The group considered that it might be appropriate for the ACSQHC to investigate the development of graphic design guidelines in collaboration with the TGA. Is it preferable to express the concentration of oral liquid medicines as mg/mL and/or by ratios or as a percentage? For injectable medicines, should there be a consistent format for the presentation of strength? 10 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Outcome of discussions The group considered that it would be preferable to have the concentration of oral liquids expressed consistently as mg/mL. The current TGO states that where the goods are a liquid and include an active ingredient which is a liquid, the quantity of active ingredient must be expressed as the appropriate amount of the active ingredient, either by weight or volume, in a stated volume of the goods. This could be made more explicit in the current TGO. The group considered that for injectable medicines it is preferable to have the strength expressed in mg (or unit used)/mL (or unit used) as well as total amount/vial. This may decrease errors in hospitals. The group considered that it should be mandatory to specify both on the label, which would require the current TGO to be modified. The group noted that for single use vials the current TGO requires quantity per volume only. Is there a need to review and update the list of excipients included in the First Schedule to TGO 69 which are required to be declared on the label of medicines? Outcome of discussions The list of excipients in the First Schedule of the current TGO 69 should be reviewed and updated. The TGO should be updated with regard to the expiry date for eye preparations. The group noted that the current required expiry date of 4 weeks in the TGO no longer applies to all products, as there are now products available with preservatives that enable longer expiry dates after opening. B. Look-alike sound-alike names (LASA) – Prescription and nonprescription registered medicines Original option proposed 1. Incorporate FDA/EMA-style requirements for proposed names into a revised Therapeutic Goods Order2. Proposed names should not: a. Be phonetically (sound like) or visually (look like) similar to existing medicine names or names pending approval; b. Convey promotional, misleading, unsubstantiated, or inappropriate claims. Additional guidance would be required to support these requirements, including how they would be assessed by the regulator and in what instances additional information can be required. In general, proposed names should not be confused with the invented name of another medicinal product when in print, handwritten or spoken. When assessing the potential for confusion, product 2 Guidance for Industry, Contents of a Complete Submission for the Evaluation of Proprietary Names, US Department of Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, February 2010. www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm075068.pdf Guideline on the Acceptability of Names for Human Medicinal Products Processed Through The Centralised Procedure, European Medicines Agency, December 2007. www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Regulatory_and_procedural_guideline/2009/10/WC500 004142.pdf 11 R13/272171 VERSION 4 characteristics such as indication, dosage form, route of administration, patient and prescriber population should also be taken into consideration. 2. Develop and introduce electronic screening of proposed medicine names, consistent with the US FDA Phonetic and Orthographic Computer Analysis (POCA) software. The FDA has made the source code and the supporting technical documentation for the POCA tool available on disk to public parties for further development3. Discussion The discussion applied to both prescription and non-prescription medicines. The group noted that Health Canada requires the sponsor to provide a risk assessment of the proposed medicine brand name which can include phonetic/orthographic computer analysis (POCA) screening of the name. It was noted that POCA is available royalty-free to other regulators to use or modify for any purpose. The FDA does not provide technical support for the software program. The group considered that it should be mandatory for sponsors to screen for phonetically or visually similar existing medicine names and that this should be included in the dossier section of how to submit to the TGA evaluation process. It was noted that there may be difficulties for the sponsor to compare their name of medicine with one pending approval by the regulator, but that in Canada the regulator screens the proposed name against any pending name approvals. The group acknowledged that POCA may not be current for all available medicine names and would also have to be adapted to Australian conditions, taking into account phonetic differences in speech and pronunciation between the US and Australia. For registered non-prescription medicines: The group considered that it may be unclear what is meant by “promotional” in option 1b and that there would be differences in the naming requirements for prescription and nonprescription medicines. The group discussed various examples of what is promotional and/or misleading. The group considered that if the same medicine was labelled individually in separate products for a series of different uses, such as migraine, back pain and period pain, this could be considered promotional and result in the consumer taking an overdose of the same medicine, as they may not realise it is the same active ingredient packaged for use for different indications. However, this was not an issue if the indications were provided together on the one product (See umbrella branding discussion). The group, however, considered that a descriptive word in the brand name, such as “Osteo” to describe a different use for a paracetamol product was not promotional as it focuses use of the medicine for a particular indication, noting also that the dosage and strength of the active ingredient for this product is higher than other products containing only paracetamol. In this case, use of the term “Osteo” should be valuable in discouraging its use for other indications, such as common headache, where a lower dose is recommended. 3 Federal Register, Vol. 74, No 30, Tuesday, February 17, 2009, Notices. www.fda.gov/OHRMS/DOCKETS/98fr/E9-3170.pdf 12 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Outcome of discussions For prescription and non-prescription medicines. The requirement that proposed names “MUST NOT” (instead of “should not”) be phonetically or visually similar to existing names or names pending approval should be made mandatory and included in the TGO (Option 1a). This should apply to both prescription and non-prescription medicines. It was proposed that the sponsor would ensure that names are not phonetically or visually similar to names of products that are already on the ARTG but that the TGA would screen names of medicines that are pending registration against the proposed names. A guideline should be available which explains what is meant by phonetically or visually similar to existing or pending names. This guideline should be established in consultation with Medicines Australia, Generic Medicines Industry Australia and Australian Self Medication Industry. The TGA should investigate the use of POCA. The group agreed that promotional, misleading, unsubstantiated, or inappropriate claims should not be conveyed on prescription medicines. Regarding non-prescription medicines, the group agreed that clarification is needed as to what is considered “promotional” in a brand name, as consumers self select nonprescription products by symptoms described on the packaging as well as brand name. Therefore, further discussion with stakeholders, including ASMI and the Consumer Health Forum is necessary. Original option proposed 3. Use of ‘Tall Man Lettering ‘in a dispensing setting but not on the main label of the medicine, except in limited and specific circumstances. A standardised national ‘tall man lettering’ (TML) approach for improving medication safety has been released by the Australian Commission for Quality and Safety in Health Care (the Commission)4. Implementation of this option would require developing guidelines for adding names to the list, notifications and thresholds for confusion. Options include: a. Adoption of the guidelines in a dispensing setting only rather than on the main label of a medicine; and/or b. Require certain products to have Tall Man lettering. It may be appropriate for products identified as high risk, for example due to a narrow therapeutic window or patient dependency, to be required to have Tall Man Lettering to reduce the risk of confusion, however this may be best addressed on a case-by-case basis. For example, in the UK Tall Man Lettering is advocated for use on medicines which contain cephalosporins5. 4 Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, National Standard for the Application of Tall Man Lettering. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, Sydney 2011. 5 www.mhra.gov.uk/SearchHelp/GoogleSearch/index.htm?q=Guidelines%20for%20tallman%20lettering 13 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Discussion The discussion regarding Tall Man lettering only applied to prescription medicines. The group noted that FDA had a Tall Man lettering list and that the UK list only included cephalosporins. Currently the ACSQHC has a list which includes 100 medicines and that the list should be kept to about that number of medicines, otherwise the measure may not be effective. The group considered that at this stage it is too premature to implement Tall Man lettering. Outcome of discussions For prescription medicines only: Since the most powerful use of Tall Man lettering is at the prescribing and dispensing stage, that Tall Man lettering not be used on “retail” packaging of prescription medicines at this time. The ACSQHC to consider a national list for dispensing and prescribing software as Tall Man lettering is more effective in preventing mistakes by health professionals rather than consumers. Original option proposed 4. Provided that changes are made to active ingredient prominence and generic medicines/SBMP naming, take no additional specific action. Improvements in active ingredient prominence would have an impact on consumer recognition of both the active ingredient and brand. It is anticipated that proposed recommendations for generic medicines will contribute to reducing medicine confusion resulting from LASA names. Outcome of discussions The group considered that this was not an option for either prescription or non-prescription medicines as changes to active ingredient prominence and generic/SBMP naming was not seen as sufficient to address problems with look-alike sound-alike names. C. Look-alike packaging – Prescription and non-prescription registered medicines Original option proposed 1. Incorporate new requirements for proposed packaging into a revised Therapeutic Goods Order. Proposed packaging should: a. Not be visually (look like) similar to existing medicine packaging; b. Be readily differentiated from other products in a sponsors portfolio, particularly where a range of different strengths or methods for administration are available. 14 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Other ways of decreasing the likelihood of dispensing errors include bar code scanners and automation in dispensing. A revised Therapeutic Goods Order (or Guidance) could be based on the graphic design of medication packaging developed by the National Patient Safety Agency in the UK6 to address issues with look-alike packaging. Original option proposed 2. Provided that changes are made to active ingredient prominence and generic medicines naming, take no additional specific action. Discussion The discussion included prescription and non-prescription medicines. Industry noted that corporate branding across a range of products - while still common for both prescription and registered non-prescription medicines - was now being discouraged by industry, health professionals and consumer groups. This is because it was widely acknowledged that confusion could be caused by some applications of this type of packaging. Industry also noted that it could be problematic if two different sponsors are preparing submissions to the TGA and would not be aware of the others packaging, which may, by chance, be similar. The TGA would need to be proactive in identifying this potential problem. The group noted a report of confusion when a manufacturer changed the colours used to identify water for injection and saline from the usual accepted standard of blue and green respectively. The group considered that standardisation of colours would help reduce errors in hospitals. Currently, colours are standardised by convention rather than regulation or guideline. For non-prescription medicines, the group noted that the brand was an inherent part of marketing strategy and corporate image is considered by industry one way consumers identify the product. However, the issue of same packaging across a product range is intrinsically linked to umbrella branding where the same product name and similar packaging might be used for multiple products, and contain the same or completely different active ingredients. The group considered that different requirements may be needed when assessing nonprescription medicines for look-alike packaging, due to corporate and umbrella branding and that further discussion will be needed with industry (ASMI and CHC) to determine what is acceptable when the TGA assesses the product for registration (See also discussion on umbrella branding). The group considered that “no action” was not an option for both prescription and nonprescription medicines as changes to active ingredient prominence and generic/SBMP naming was not seen as sufficient to address problems with look-alike packaging. 6 Design for Patient Safety, A Guide to the Graphic Design of Medication Packaging, National Patient Safety Agency, NHS, 2007. www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?EntryId45=63053 15 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Outcome of discussions Incorporate option 1a and 1b into a revised TGO to pertain to prescription medicines i.e. that proposed packaging should: a. Not be visually (look like) similar to existing medicine packaging; b. Be readily differentiated from other products in a sponsors portfolio, particularly where a range of different strengths or methods for administration are available. Further discussion is needed for non-prescription medicines for look-alike packaging (ASMI, CHC and other stakeholders) to determine what is acceptable when the TGA assesses the product for registration. Develop guidelines in conjunction with industry for accepted practice for packaging which could be based on the National Patient Safety Agency “Design for Patient Safety: A Guide to the Graphic Design of Medication Packaging”. This work could be undertaken by the ACSQHC. D. Blister strip labelling – Prescription and non-prescription registered medicines Original option proposed 1. Mandate that the brand name, active ingredient and strength must be displayed over each dosage unit. 2. Mandate that the batch number and expiry date should be printed, rather than embossed, in a location on the blister strip that will not be disturbed during the use of the product. Printing rather than embossing allows consumers and health professional to more clearly see the batch number and expiry dates. This would be of greatest benefit to those who are vision impaired, including the elderly. However, embossing the batch number and expiry dates during the production process was claimed in the submissions to be the most efficient method of providing this information on the blister pack. There are blister strips available on the Australian market with the batch number and expiry date printed on the blister pack. Discussion The discussion included both prescription and non-prescription medicines. The group noted the current requirement of TGO 69 for blister packs is that the brand names, active ingredient and strength must be displayed over every second unit in the blister pack. The group noted that it is a particular issue for hospitals where small quantities are dispensed and the batch number and expiry date may not remain on the blister pack. It is also a problem for consumers who may cut their blisters packets into smaller pieces when travelling. 16 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Industry stated that consumers should be educated to leave their medication inside the primary pack. Industry noted that the cost of changing to printing instead of embossing the batch and expiry on blister packs would be significant and that in the case of metal blister packs embossing is preferred as the print rubs off. Industry stated that good quality assurance of embossing ensures that the batch number and expiry can be easily identifiable and that the variability seen currently could be improved by better quality assurance. Outcome of discussions For prescription and non-prescription medicines. Not mandate that the brand name, active ingredient and strength be displayed over each dosage unit. Instead make no change to the current TGO requirement which states that the brand name, active ingredient and strength be displayed over every second dosage unit. Allow both embossing and printing of batch number and expiry dates but discuss ways to optimise embossing with industry. However, printing should be the preferred option for the batch number and expiry date with further discussion with industry regarding a reasonable solution, noting the costs involved. Encourage industry to specify the month on blister strip packaging by name rather by number (e.g. Dec or December rather than 12) Encourage consumers to leave medications inside the primary pack through education strategies. E. Small containers – Prescription and non-prescription registered medicines Original option proposed 1. Retain current TGO 69 requirements, (which requires the provision of a pack insert that provides detailed instructions for use if the directions cannot fit on the primary pack), but incorporate an increase in minimum font size for the active ingredient to 2mm (currently not less than 1.5 millimetres). 2. Mandate that, when detailed instructions for use cannot fit on a small container, the goods must be enclosed in a primary pack and a package insert included in the pack. 3. Incorporate relevant components from the UK NPSA Guidelines for labelling injectable medicines7 and similar requirements from anaesthetic labelling into TGO 69 to improve labelling of small containers in general. This could include the use of colour and other graphic elements as well as consumer testing. (Rationale: Injectable medicines and 7 Design for Patient Safety, A Guide to Labelling and Packaging of Injectable Medicines, National Patient Safety Agency, NHS Edition 1, 2008. www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?entryid45=59831 17 R13/272171 VERSION 4 medicines used in anaesthesia are often contained in small vials or ampoules. Therefore, using the principles of this guidance for labelling and packaging applicable to these types of containers may be useful for improving the legibility of small containers in general). Discussion The discussion included both prescription and non-prescription medicines. Industry stated that an increase in font size for much of the label content on small containers would increase production costs and that proposed changes must be practical. The impact to industry would be taken into account when preparing the Regulation Impact Statement (RIS), which must be completed before any change can be implemented. Outcome of discussions For prescription and non-prescription medicines. F. The font size of active ingredient only should be increased to 2 mm (approximately 6 point) but that font sizes for other information would not be mandated. Mandate that, when detailed instructions for use cannot fit on a small container, the goods must be enclosed in a primary pack and a package insert included in the pack (option 2 above). ACSQHC to work with the TGA to develop guidelines similar to the UK NPSA Guidelines for consistency. Determine the impact of cost to industry of an increase in font size when developing the RIS. Undertake further discussion with industry regarding: o The impact of increased font size on the available space on the primary container and how the mandatory requirement might be met. o Whether there should be different requirements for prescription and nonprescription with regards to small containers. o The possible use of smartphone QR codes, as some information which may not fit on the primary container could be provided in a QR code. Pack Inserts – Prescription and non-prescription registered medicines Original option proposed 1. Include a statement in TGO 69 describing what advertising material will not be permitted to be included as a separate pack insert or incorporated into an approved pack insert. (Rationale: advertising of prescription medicines direct to consumers is not allowed under current legislation). 2. Include a statement in TGO 69 that a pack insert must be in a form separate to the packaging i.e. it cannot be printed on the inside of the carton. 18 R13/272171 VERSION 4 3. Use Quick Response (QR) codes that enable the consumer, with use of their smartphone, to access larger amounts of information which could be more easily read. 4. Retain the current requirements as set out in TGO 69 which states that if there is insufficient space on the label of the container or on the primary pack to include directions for use, a statement should be included in a label on that container or primary pack to the effect that those directions for use are set out on a leaflet inserted in the primary pack. Discussion The discussion included both prescription and non-prescription medicines. Industry considered that promotional advertising material was already not allowed and that there were sufficiently clear provisions in Industry Codes of Conduct. It was noted that patient support programs are also monitored under this Code. The group therefore agreed that it was not necessary to have a statement in the TGO about advertising material as this was duplication. There was discussion regarding a pack insert being printed on the inside of the pack. There was general agreement that this was not preferred as the packet may be torn or discarded by the consumer and therefore any instructions on the inside of the pack would be gone. The group considered that exemptions could possibly considered in exceptional cases. Outcome of discussions For prescription and non-prescription medicines. No change to the current requirements as set out in TGO 69: which states that if there is insufficient space on the label of the container or on the primary pack to include directions for use, a statement should be included in a label on that container or primary pack to the effect that those directions for use are set out on a leaflet inserted in the primary pack (option 4 above). No need to include a statement in TGO 69 regarding advertising material. Industry to supply further examples of directions for use inside packaging to examine whether this is appropriate or not and whether some exemptions might be considered. QR codes should be utilised where possible but not mandated. G. Labels and packaging advisory committee – Prescription and nonprescription registered medicines Original option proposed Maintain the Labels and Packaging External Reference Group. This Group could develop details regarding the terms of reference and guidelines for the establishment of a Labels and Packaging Advisory Committee. The Group would also provide 19 R13/272171 VERSION 4 advice regarding mandatory requirements as well as guidelines for Labelling and Packaging in accordance with current best practice for labels and packaging. Establish a Labels and Packaging Advisory Committee. It is envisaged that the role of the Labels and Packaging Advisory Committee would be to provide advice on medicine names as well as packaging presentations with regard to patient safety for both prescription and non-prescription medicines. This could be on a case by base referral basis from the TGA Delegate assessing a submission. In making these decisions the Committee would consider legislative requirements, promotional or misleading claims and safety concerns and confusion with another medicinal product. Discussion The group considered that a Committee for Labels and Packaging would be helpful. The group was advised that for this Committee to be established as a statutory Committee a change to the Regulations would be required. It was envisioned that the reference group would need to be retained for approximately one year while the Committee was being formally established. Outcome of discussions H. Agreement for the establishment of a Labels and Packaging Advisory Committee, noting that the reference group would continue in the interim until the completion of the establishment process. Dispensing Label Space – Prescription medicines only Original option proposed 1. Specify mandatory requirement for dispensing label space and its location (Prescription medicines only). Consistent with UK guidelines8, where space permits, the dispensing label space should be on the front label either directly below or immediately adjacent to the brand name and active ingredient. 8 Best Practice Guidance on the Labelling and Packaging of Medicines, Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, May 2012. www.mhra.gov.uk/Howweregulate/Medicines/Labelspatientinformationleafletsandpackaging/Overviewoflabe lspatientinformationleafletsandpackagingformedicines/index.htm Design for Patient Safety, A Guide to the Graphic Design of Medication Packaging, National Patient Safety Agency, NHS, 2007. www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?EntryId45=63053 20 R13/272171 VERSION 4 On small containers or containers that cannot accommodate a dispensing label, dispensing pharmacists should use a clear flag label to create additional space for the dispensing sticker without obscuring information on the packaging. Products intended for use only in a hospital setting would be exempt from these requirements. 2. Mandate a change to the space for dispensing label size to be consistent with UK Guidelines 80 x 40 mm is the size of dispensing labels used in Australia. However, it has been proposed that the space available on packages and thus the label size should be harmonised with UK label size of 70 x 35 mm. Discussion The discussion included prescription medicines only. The group noted that only a small percentage of prescription medicine packaging had sufficient space for a dispensing label. Further, it was problematic to accommodate dispensing label space on small containers. The group agreed that decreasing the size of the label may potentially decrease the size of the font on the dispensing label and thus its readability. Consumers considered that the font size should be as large as possible as the majority of patients who are taking medicines are elderly and are more likely to have vision impairment. Industry noted that if the dispensing label size was changed to the UK standard size (70 x 35 mm) more products might be available with sufficient and dedicated dispensing label space. However, the group considered that the current dispensing label was already too small and that the current font size on dispensing labels was not considered to be consistent with quality use of medicines. The group discussed whether the use of bar codes might aid consumers access information by for example allowing “talking labels” or enlarged versions of the information. Industry noted that with the price margin pressures on generic medicines, bottles are once again becoming the predominant container used rather than packets. Space for a dispensing label was not as easy to accommodate on this type of container compared with medicines in packets/boxes. The discussion also focussed on problems of labelling of small containers in general with the group noting that important information is sometimes being masked by the dispensing label. The group noted that “butterfly” labels or clear flag labels could be used to alleviate the problem. The group agreed that standards for the labelling of small containers needed improvement. Outcome of discussions For prescription medicines only, further advice is needed from professional pharmacy groups (the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia, the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia and the Pharmacy Guild) before consideration of any change is made to the dispensing label size. 21 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Regarding labelling of medicines in small containers, further discussion should take place amongst professional pharmacy groups such as the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia regarding options on how best to label these containers. Encourage an update to the Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary (APF) so that definitive guidance is provided on how to label medicines during dispensing, with particular reference to how to label small containers. 22 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Non-prescription registered medicines only I. Standardised Information: Medicine Information Box Original option proposed 1. Utilise the medicines information box to include mandated information in a standardised format with agreed mandatory headings. In addition: The wording of the headings to be made more consumer focused, using headings such as “How to take” instead of “Directions”; 2. Require particular headings for information but not require a standardised box format and remove the need for the title “medicine information box”. 3. Feasibility of use of Quick Response (QR) codes that enable the consumer, with use of their smartphone, to access information about the product. Discussion The discussion included non-prescription registered medicines only. The group considered that a standardised format for the medicines information box would allow consumers to become familiar with the layout and enhance readability. Regarding QR codes, the group considered that these should be encouraged rather than mandated. There was concern, however, of how to regulate what the consumer will link to, as promotional material was considered to be inappropriate. There was also concern that use of electronic codes could cause crowding of the packaging and therefore use would be counterproductive to what was trying to be achieved by Labelling and Packaging reforms. It was noted that industry currently self regulates the content of the electronic codes. The group also noted that the bar codes are most commonly used to track product from the manufacturer to end destination but that electronic codes are also being used to inform consumers regarding use of the medicine, other treatment options and other organisations available for further information. Further work is also needed to ensure the use of standardised Australian Medical Terminology on all electronic coding. Outcome of discussions For non-prescription medicines only. Agreement was reached for a standardised medicine information box with mandatory headings similar to that used in the USA, with further discussion with stakeholders required on formatting and title headings. 23 R13/272171 VERSION 4 J. Encourage but not mandate QR codes so that information can be provided to consumers in this way, ensuring the information accessed via a QR code is compatible with the approved product information (if required) and non-promotional. The Code of Conduct Committee (not TGA) to investigate whether self regulation of promotional material that may be potentially linked through use of QR codes is appropriate or sufficient. Umbrella Branding (Look-alike medicine branding) “Umbrella” or “family” branding describes the situation where a sponsor markets different products under the one brand name (e.g. Strepsils lozenges, Strepsils mouthwash, Strepsils Family Cough Medicine). Original option proposed 1. Incorporate the current requirements for umbrella branding in the Australian Regulatory Guidelines for Over the Counter Medicines9 into a revised Therapeutic Goods Order to create enforceable requirements. (Currently, applications requesting to use a currently registered brand name for a new product containing different active ingredients for the same or different indication may not be accepted for registration as the duplicate use of the same brand name may cause significant consumer or health care practitioner confusion). 2. Adopt guidelines for umbrella branding from the UK or Canada. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Howweregulate/Medicines/Namingofmedicines/index.htm http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/brgtherap/applic-demande/guides/drugsdrogues/lasa_premkt-noms_semblables_precomm-eng.php These Guidelines allow a portion of the brand name (the umbrella segment) to be used to create a range of products only if there are no safety or efficacy concerns resulting from the products sharing the same portion of the brand name. The Guidelines encourage the development of new product names without umbrella segments for each product but will consider each application on its own merit. 3. Develop specific guidelines for Australia and New Zealand based on a combination of the guidelines of the UK or Canada. 4. Retain some or all of the proposed recommendations in the consultation paper: not allow listed products to be marketed under the same name as a registered product; not allow a product containing the same active ingredient to be marketed for a subset of symptoms; and not allow the same brand name to apply to products that have different active ingredients. 9 Australian Regulatory Guideline for over-the-counter medicines, Appendix 3: Guidelines on presentation aspects of OTC applications, version 1.0, October 2012. www.tga.gov.au/industry/otc-argom-app3.htm 24 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Discussion The discussion included non-prescription medicines only (including registered complementary medicines). Industry proposed that there should be label testing prior to the implementation of any change and that change should be consistent with international best practice. (TGA has earlier committed to undertake label testing of major options). While the group considered that the minimum change would be to develop specific guidelines for umbrella branding for Australia and New Zealand as per option 3 above, the strong majority view of the group was that interpretation of any guideline would still be subjective and that the current challenges for consumers and healthcare professionals (including poison centres) would not be solved as there is already a lack of compliance with the current guideline in some cases. The group identified that umbrella branding of products may cause delays in the treatment of poisoning/overdose cases as patients usually only state the umbrella brand name on presentation to the emergency department. If there are multiple products with the same brand name, which may contain different active ingredients or different combinations of active ingredients, there may be a critical delay in treatment until the active ingredient/s can be identified. Emergency department presentations only very rarely bring the packets to hospital in accidental or deliberate overdose cases. If a brand name was unique to only one product it would be much easier to identify what a patient had taken. Consumer representatives considered that consumers were not aware that there may be a difference in efficacy between a listed product, which is not assessed for efficacy by the TGA, and a registered product. On the other hand, there may be a greater chance of adverse event as when a registered medicine is unexpectedly present in a product in an umbrella medicine range usually associated with listed complimentary medicines. A significant majority of the group considered that a product containing the same active ingredient should not be marketed for subsets of symptoms as this may lead to potential overdoses if consumers do not realise that they are taking the same active ingredient for different symptoms. This is especially an issue for paracetamol-containing products as, for example, the daily dose for osteoarthritis (4000 mg) is at the top of the acceptable total daily dose for this substance. Industry emphasised that branding was an important marketing tool and important in patient communication. It also represented a significant investment made over several years. However, the group considered that consumer safety should be foremost in use of brand names and that this must be foremost when selecting brand names and umbrella branding strategies, as certain branding poses risks to consumers as identified above. The ASMI representative considered that the best option was to develop specific guidelines for Australia and New Zealand as identified in option 3. However, the majority of the group considered that the component parts of option 4 should be further investigated as they would provide the best safety outcome for consumers as well as support quality use of medicines. 25 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Outcome of discussions For non-prescription medicines only: Further consultation with industry and other stakeholders to be undertaken prior to the implementation of the principles outlined in point 4 namely: o not allow listed products to be marketed under the same name as a registered product; o not allow a product containing the same active ingredient to be marketed for a subset of symptom in different presentations; and o not allow the same brand name to apply to products that have different active ingredients. It was agreed that an outright ban on umbrella branding was not warranted – for example, consumers value the recognition of Panadol as comprising differing paracetamol formulations, and that use of descriptors such as “rapid”, “osteo” and “forte” have genuine meaning to consumers in differentiating products. Further discussion is needed with industry and other stakeholders to enable a pragmatic approach to be developed in cases when umbrella branding poses a significant risk to consumer safety and therefore should not be used, and when it is acceptable (and potentially desirable) to use umbrella branding. Consideration should also be given to what is happening in the UK and Canada regarding umbrella branding. (For example, Health Canada’s latest draft guidance for look-alike soundalike attributes has reference to umbrella branding. It proposes eight criteria for initially reviewing proposed brand names). K. Warning statements (ingredient alert) for products containing paracetamol and ibuprofen Original option proposed 1. Implement the proposed regulatory change which requires a warning for paracetamol and ibuprofen on the front of the label which states “Contains ibuprofen/paracetamol X mg. Consult your doctor or pharmacist before taking other medicines for pain or inflammation”, with the following considerations a. Remove the requirement for the same warning to be repeated with the other medicine information. b. Work with stakeholders to ensure the adequacy of the warning statement to ensure that it is accessible to consumers - i.e. the wording and placement of the warning together with user testing. 2. Implement a warning statement that is more general about avoiding double-dosing or overdosing of medicines containing the same active ingredients. Discussion The discussion included non-prescription medicines only. 26 R13/272171 VERSION 4 Significant majority of the group agreed that both paracetamol and ibuprofen products should have a warning label as described above. The group noted that advice for pharmacists regarding these types of warnings is already included in the Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary (APF) for scheduled medicines. ASMI questioned why this type of warning should apply only to paracetamol and ibuprofen and not to a wider range of products. ASMI also noted that a similar warning is already on the back of the packet for products containing paracetamol and therefore to present it on the front may be repetitive. However, consumer representatives considered that the current warning on the back of the packaging is not sufficiently prominent and needed to be on the front, and noted that it is on the front in some countries. The group noted that these two medicines were predominant in reported poisonings to hospital emergency departments and in calls to poisons centres. Also it was not just double dosing that was of concern. Consumers often confused the two medicines thinking they are the same and it was noted that a NPS study indicated that consumers were often not aware of what active ingredient is present in the medicine, which may lead to overdosing, particularly in children. Also, consumers may inadvertently take medicines which may be contraindicated due to their medical condition because they are not aware what the active ingredient is. The group noted statistics from the NSW Poisons Information Centre which showed that there were about 4500 poisonings with paracetamol and 1000 with ibuprofen per year. The group considered that it was important that the consumer be made aware of the risks associated with taking too much of medicines such as ibuprofen and paracetamol, taking into account the numerous products containing these active ingredients available on the Australian market. Outcome of discussions Further discuss preferred options with consumer and industry stakeholders. Either: o Implement a warning statement for both paracetamol and ibuprofen with further discussion to take place about the actual wording; OR o Implement a more general warning statement about avoiding double-dosing of medicines containing the same active ingredient. At next revision, the APF be updated with regard to advisory warning labels to inform pharmacy practitioners how best to label these types of products. 27