Economic Growth in India and Bangalore

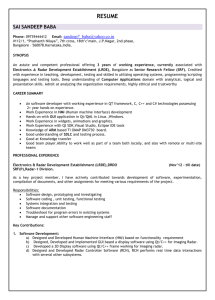

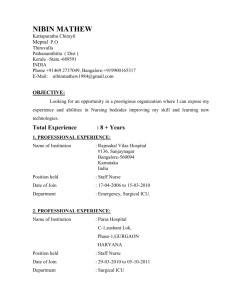

advertisement