Local Opportunity Structures and Intergenerational Neighborhood

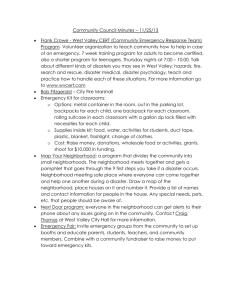

advertisement