(Word Version)

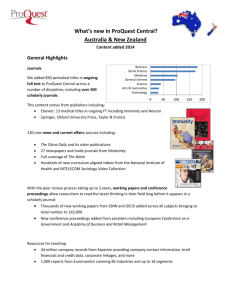

advertisement