Employee Engagement Instruments-A Review of the

advertisement

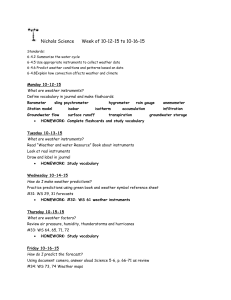

Running head: EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 1 Employee Engagement Instruments: A Review of the Literature Sowath Rana* University of Minnesota ranax031@umn.edu Alexandre Ardichvili University of Minnesota ardic001@umn.edu *Corresponding author Submission Type: Working Paper Stream: Employee Engagement Submitted to the UFHRD Conference 2015, University College Cork, Ireland EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 2 Abstract Purpose: The purpose of this study is to conduct a comprehensive literature review of the major instruments used to measure employee engagement. Methodology: We conducted a structured review of published instruments measuring employee engagement in the current literature. Findings: This study provides numerous significant findings with regard to what scales are available, what their properties are, and how they have been used. Implications: Our findings suggest that the instruments require more rigorous testing and that more evidence of validity and reliability for the scales is needed. In addition, scholars and practitioners should pay specific attention to the appropriateness of the scales before employing any of them. Originality/Value: We believe that this paper can make a significant contribution to the literature on engagement. It aims to provide a comprehensive review of the major engagement instruments as regards a specific set of assessment criteria. Keywords: Employee engagement, work engagement, instrument, measurement, operationalization EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 3 Employee Engagement Instruments: A Review of the Literature Employee engagement has generated great interest among Human Resource Development scholars over the past few years (Kim, Kolb, and Kim, 2012; Rana, Ardichvili, and Tkachenko, 2014; Rurkkhum and Bartlett, 2012; Shuck, Reio, and Rocco, 2011; Shuck and Wollard, 2010; Soane, Truss, Alfes, Shantz, Rees, and Gatenby, 2012; Wollard and Shuck, 2011). Engagement is defined as the “harnessing of organization members’ selves to their work roles” (Kahn, 1990, 694). When engaged, organizational members express themselves cognitively, behaviorally, and emotionally during role performance (Kahn, 1990; Shuck and Wollard, 2010). In contrast, personal disengagement refers to the “uncoupling of selves from work roles,” during which process people withdraw and defend themselves physically, cognitively, or emotionally while performing those tasks (Kahn, 1990, p. 694). Over the past two decades, significant efforts have been made by scholars to study engagement and by practitioners to develop organization development (OD) related interventions to raise the levels of engagement among organizational members. Such strong interest is not surprising, given that engagement has been shown to be related to a number of important organizational outcomes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment (Saks, 2006), organizational citizenship behavior (Rurkkhum and Bartlett, 2012; Saks, 2006); intention to turnover (Shuck et al., 2011); and performance (Kim et al., 2012). Despite the attention, a debate still exists among engagement scholars over the operationalization and measurement of the construct. Kahn (1990, 1992), whose work has been largely credited with laying a foundation that undergirds much of the engagement research, did not offer an operationalization of the construct. The Maslach-Burnout Inventory (MBI), developed by Maslach and Leiter (1997), has been heavily criticized for measuring engagement EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 4 along the same continuum as the three dimensions of the burnout construct: exhaustion, cynicism, and efficacy (Schaufeli, Salanova, Gonzalez-Roma, and Bakker, 2002). Later, the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES), developed by Schaufeli et al. (2002), has become one of the most widely used instruments in engagement research. However, despite its popularity, questions still arise over the issue of “construct redundancy” between engagement and burnout (Cole, Walter, Bedeian, and Boyle, 2012, p.1576). Cole et al. (2012) found that the UWES is “empirically redundant with a long-established, widely employed measure of job burnout (viz, MBI)” (p.1576). Finally, Soane et al.’s (2012) study – seemingly the only publication in the HRD literature that has attempted to develop an engagement instrument – took a slightly different route and proposed the Intellectual, Social, Affective Engagement Scale (ISA Engagement Scale), which comprised of three components of engagement: intellectual, social, and affective engagement. The aforementioned examples demonstrate that despite the intuitive appeal of the engagement concept, there is little agreement as to how the construct should be measured. Therefore, it is especially important for HRD scholars, practitioners, and students to understand the strengths and shortcomings of the various popular engagement instruments in order to advance research on the topic. The purpose of this study, therefore, is to conduct a comprehensive literature review of the major instruments used to measure employee engagement. The overarching research questions for this study are: (1) What instruments are available for measuring employee engagement? (2) What are the characteristics of those instruments? and (3) What are the strengths and weaknesses of these instruments? EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 5 The seven instruments reviewed in this study are: the Gallup Workplace Audit (GWA; Harter, Schmidt, and Hayes, 2002), the UWES (Schaufeli et al., 2002), the Psychological Engagement Measure (May, Gilson, and Harter, 2004), the Job and Organization Engagement Scales (Saks 2006), the Job Engagement Measure (Rich, LePine, and Crawford, 2010), the Employee Engagement Survey (James, McKechnie, and Swanberg, 2011), and the ISA Engagement Scale (Soane et al., 2002). The unit of analysis for the study is the instrument; thus, reasonable attempts were made to obtain a full copy of the instruments reviewed along with any relevant full-text publications. We believe that this paper can make a significant contribution to the literature on engagement. It aims to provide a comprehensive review of the major engagement instruments as regards the assessment criteria discussed above. In addition, findings from this study will offer important insights and implications to HRD scholars and practitioners who are interested in conducting engagement research. Methodology We conducted a structured review of published instruments measuring employee engagement. We searched various databases including Google Scholar, Eric, Emerald, PsycInfo, and ABI/Inform. We also reviewed academic journals such as Academy of Management Journal, Human Resource Development International, Human Resource Development Review, Journal of Applied Psychology, Journal of Organizational Behavior, books, and other relevant publications. These journals were selected because of their recognized status as leading HRD, management, and applied psychology journals that regularly publish engagement-related literature. Finally, we traced the list of references of the publications in order to identify potential relevant instruments. EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 6 Search terms included: employee engagement, work engagement, engagement, tool, assessment, instrument, or evaluation. The tools had to be available in English and accessible to scholars and researchers, designed for quantitative analysis. Furthermore, information had to be available on psychometric and other evaluations, including validity and/or reliability. We limited our searches to after 1990 because the term ‘engagement’ was first coined by William Kahn in his publication in the Academy of Management Journal in 1990. Upon identifying the available instruments, we sought to obtain a copy of each publication of the instruments. The measures and their corresponding publications were carefully reviewed by the authors of this paper. The assessment framework for the review of engagement instruments centers around a set of criteria: (a) instrument description, (b) psychometric properties, and (c) criticisms of the instrument. The description criterion focuses on the instrument’s constitutive definition of engagement, development (how it was developed; e.g., through building on other instruments), development date, intended purpose, dimensions, and population tested. The psychometric properties focus specifically on evidence of validity and reliability provided by the publication authors. Finally, the study also discusses any documented comments or criticism of the instruments. Results Our review of the literature yielded seven relevant instruments aimed at measuring the engagement construct. As Table 1 suggests, we identified the types of the instruments and sample items of the measures. We also provided a summary of the purpose of the publication of each instrument, the definition(s) of engagement used, and the theoretical framework that undergirds the development of each measure. We also summarized the population and samples of each study and reported the reliability and validity of each instrument. 7 Tool and Reference The Gallup Workplace Audit (GWA) Harter, Schmidt, and Hayes (2002) The Utrecht Work Engagem ent Scale (UWES) Schaufeli, Salanova, GonzalezRoma, and Bakker (2002) May et al.’s Psychologi cal Engageme nt Measure 12-item questionnaire; five-point scale ranging from ‘Strongly Disagree’ to ‘Strongly Agree’ Sample items: I know what is expected of me at work. The mission or purpose of my company makes me feel my job is important. Publication’s intended purpose Using meta-analysis to explore the relationship between “employee satisfactionengagement” and various outcomes – customer satisfaction, productivity, profit, employee turnover, and accidents (p. 268). Definition of engagement “Individual’s involvement and satisfaction with as well as enthusiasm for work” (p. 269) 17-item questionnaire; seven-point scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘always/everyday’ To examine the factorial structure of a new instrument to measure engagement Sample items: When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work. (Vigor) I am enthusiastic about my job. (Dedication) When I am working, I forget everything else around me. (Absorption) 13-item questionnaire measuring engagement (cognitive, emotional, and physical); five-point scale ranging from ‘Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree’ To assess the relationship between engagement and burnout and examine the factorial structure of the MaslachBurnout InventoryGeneral Survey (MBI-GS) To explore the determinants and mediating effects of the three psychological conditions – meaningfulness, safety and “A positive, fulfilling, workrelated state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (p. 74) Instrument Description Development Developed based on studies of work satisfaction, motivation, supervisory practices, and work-group effectiveness Built on the burnout literature (particularly the MBI scale); argues that burnout and engagement should be measured independently with different instruments. Population Tested Reliability Validity This study was based on a Gallup database of 7,939 business units – not individual employees – in 36 companies. Cronbach’s α (overall instrument) at the business-unit level of analysis = .91 The items measure “processes and issues that are actionable at (i.e., under the influence of) the work group’s supervisor or manager” (p. 269) Sample 1: 314 undergrad students of the University of Castellon, Spain Sample 2: 619 employees from 12 Spanish private and public companies. Cronbach’s α for the three dimensions: Vigor: .78 (students) and .79 (employees) Dedication: .84 (students) and .89 (employees) Absorption: .73 (students) and .72 (employees) Utilized Kahn’s (1990) definition of engagement at work Built mainly on Kahn’s (1990) study. Psychological Engagement scales were developed to measure the three components of Kahn’s psychological engagement: cognitive, 213 employees at a large insurance firm located in Midwestern US Cronbach’s α (overall psychological engagement scale) = .77 “Both overall satisfaction and engagement showed generalizability across companies in their correlation with customer satisfaction–loyalty, profitability, productivity, employee turnover, and safety outcomes” (p. 273) Three scales were developed to measure the three engagement dimensions (vigor, dedication, and absorption), in accordance with the authors’ constitutive definition of the construct Results showed that the burnout and engagement scales were significantly and moderately negatively related Three scales were developed to measure the three dimensions (cognitive, emotional, and physical) dimensions of Kahn’s theorized psychological engagement 8 May, Gilson, and Harter (2004) Saks’ Job Engageme nt and Organizati on Engageme nt Scales Sample items: Performing my job is so absorbing that I forget about everything else. (Cognitive) I get excited when I perform well on my job. (Emotional) I exert a lot of energy performing my job. (Physical) Two six-item questionnaires for job engagement and organization engagement; five-point scale ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ to ‘Strongly agree’ Saks (2006) Sample items: I really “throw” myself into my job. (Job engagement) This job is all consuming; I am totally into it. (Job engagement) Being a member of this organization is very captivating. (Org. engagement) I am highly engaged in this organization.(Org. engagement) availability – developed by Kahn (1990) on employee engagement in their work To test a model of the antecedents and consequences of job and organization engagements based on social exchange theory emotional, and physical engagement. The author built on the definitions provided by various other well-known scholars Based on social exchange theory (SET) and review of existing literature Significantly related to the three psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability 102 employees working in a variety of jobs and organizations, mainly in Canada Cronbach’s α (Job engagement scale) = .82 Cronbach’s α (Organization engagement scale) = .90 A principal components factor analysis with a promax rotation resulted in two factors that corresponded to job and organization engagements. The two scales were developed to measure the two types of engagement, as proposed by the author. Results suggested that there is a meaningful difference between job and organization engagements. Significantly related to other constructs including perceived organizational support, procedural justice, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, intentions to quit, and organizational citizenship behavior. 9 Rich et al.’s Job Engageme nt Measure 18-item questionnaire; five-point scale ranging from ‘Strongly Disagree to ‘Strongly Agree’ Rich, LePine, and Crawford (2010) Sample items: At work, my mind is focused on my job. (Cognitive) I am enthusiastic in my job. (Emotional) I work with intensity on my job. (Physical) James et al.’s Employee Engageme nt Survey 8-item questionnaire; fivepoint scale ranging asking respondents the extent to which they agreed or disagreed James, McKechnie , and Swanberg (2011) Sample items It would take a lot to get me to leave Citisales. (Cognitive) I really care about the future of Citisales. (Emotional) I would highly recommend Citisales to a friends seeking employment. (Behavioral) To draw on Kahn’s (1990) work to “develop a theory that positions engagement as a key mechanism explaining the relationships among a variety of individual characteristics and organizational factors and job performance.” (p. 617) Utilized Kahn’s (1990) definition of engagement at work To examine six dimensions of job quality (supervisor support, job autonomy, schedule input, schedule flexibility, career development opportunities, and perceptions of fairness) for their impact on employee engagement among older and younger workers in a large retail setting. Utilized Kahn’s (1990) definition of engagement at work Drew on Kahn’s (1990) theory to describe how engagement “represents the simultaneous investment” of cognitive, affective, and physical energies” (p. 617) 245 full-time US firefighters and their supervisors Cronbach’s α (overall job engagement scale) = .95 Searched the literature for scales and items that fit Kahn’s definitions of the three engagement dimensions; developed a scale that measures those dimensions Utilized social exchange theory and the norm of reciprocity as framework Reviewed relevant literature on engagement, including Kahn (1990) and Schaufeli et al. (2002) The engagement measure was developed for Citisales by an external vendor 6047 Citisales employees in 352 stores in three regions of the U.S. Cronbach’s α (overall scale) = .91 Three scales were developed to measure the three dimensions (cognitive, emotional, and physical) dimensions of Kahn’s theorized psychological engagement Significantly related to job satisfaction, value congruence, perceived organizational support, core self-evaluations, task performance, and organizational citizenship behavior The scale sought to measure the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of engagement Engagement was significantly related to other constructs, specifically supervisor support and recognition, schedule satisfaction, career development and promotion, and job clarity 10 The Intellectual , Social, Affective Engageme nt Scale (ISA engagemen t Scale) Soane, Truss, Alfes, Shantz, Rees, and Gatenby (2012) Nine-item questionnaire; seven-point scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ Sample items: I focus hard on my work. (Intellectual) I share the same work values as my colleagues. (Social) I feel energetic in my work. (Affective) To develop an engagement model that has three requirements: a work-role focus, activation, and positive affect To operationalize this model using a new measure that comprises of three dimensions: intellectual, social, and affective engagement. Proposed that engagement has three underlying facets: Intellectual engagement: “the extent to which one experiences a state of positive affect relating to one’s work role” (p. 532) Affective engagement: “the extent to which one experiences a state of positive affect relating to one’s work role” (p. 532) Social engagement: “the extent to which one is socially connected with the working environment and shares common values with colleagues” (p. 532) Review of the literature and related instruments Study 1: 540 employees of a UKbased manufacturing company Study 2: 1486 UKbased employees working for a retail organization Cronbach’s α (overall construct) = 0.91 Three scales were developed to measure the three engagement facets (intellectual, affective, and social), in accordance with the authors’ constitutive definition of the construct Results confirmed associations between engagement and three organizational outcome variables: task performance, OCB, and turnover intentions. ISA Engagement Scale explained additional variance in the three outcome variables after controlling for the UWES measure. EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 11 Discussion In this section, we discuss the findings in relation to the criteria used to evaluate the instruments. Specifically, we provide a holistic overview of the main frameworks used, definitions, populations and samples, and purposes of the instrument publications. We also discuss the issues of reliability and validity and, where applicable, provide comments on the instruments based on our review of other literature sources. Instrument Descriptions, Definitions, Theoretical Frameworks, and Development All seven instruments included in our review are questionnaire surveys with the number of items ranging from 8 (James et al.’s Employee Engagement Survey) to 18 (Rich et al.’s Job Engagement Measure). As expected, the majority of the instruments were developed based on Kahn’s (1990) definition of engagement – the “harnessing of organization members’ selves to their work roles” (p.694). Interestingly, Harter et al. (2002) – employing the GWA – conceptualized engagement as “individual’s involvement and satisfaction with as well as enthusiasm for work” (p.269) whereas Schaufeli et al. (2002) defined engagement as a “state of mind” that is characterized by “vigor, dedication, and absorption” (p.74). With respect to the theories or frameworks upon which the development of the measures was based, Kahn’s (1990) psychological conditions of engagement – cognitive, emotional and physical engagement – serve as the foundational framework for the development of the majority of the instruments, particularly the Psychological Engagement Measure (May et al., 2004) and the Job Engagement Measure (Rich et al., 2010). Other literature sources include theories of motivation and job satisfaction (GWA), the burnout literature (UWES) and social exchange theory (Saks’ Job and Organization Engagement Scales; James et al.’s Employee Engagement Survey). EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 12 Interestingly, the population samples on which the instruments were originally tested are mainly Western samples, although studies attempting to validate some of the instruments in nonWestern contexts have been conducted (e.g. UWES in Japan; Shimazu, Schaufeli, Kosugi, Suzuki, Nashiwa, Kato, Sakamoto, Irimajiri, Amano, Hirohata, and Goto, 2008). In line with this, researchers should proceed with caution when employing a Western engagement instrument in a non-Western context (Rothmann, 2014). In addition to the usual requirements of validity and reliability, one should take into account the construct equivalence and bias of engagement measures when conducting cross-cultural studies (Rothmann, 2014). Shimazu et al. (2008), for instance, found that in the Japanese context, the expected three dimensions of the UWES (vigor, dedication, and absorption) “collapsed and condensed into one engagement dimension” – which implies that in Japan, engagement should be considered a unitary construct (p.519). Moreover, the measurement accuracy of the Japanese version and the original Dutch version of the UWES was not similar, which was possibly due to the tendency of the Japanese people to suppress their positive affect and the likelihood of self-enhancement among the Dutch people (Shimazu, Schaufeli, Miyanaka, and Iwata, 2010). Hence, we should be careful when interpreting the low engagement scores among Japanese employees and high engagement scores among Western workers (Shimazu et al., 2010). Reliability Reliability refers to the extent to which a measure can produce stable and consistent results (Field, 2009; Fletcher and Robinson, 2014). For a measure to be reliable, the evaluator needs to ascertain that its results are reproducible and stable under different conditions and across different time periods. There are three most commonly used types of reliability: (a) testretest, (b) internal consistency, and (c) inter-rater. EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 13 Test-retest reliability means that if a respondent is to retake the test under similar conditions, his or her score would remain similar to the previous score (Fletcher and Robinson, 2014). Internal consistency reliability refers to the extent to which the test items measure the same construct of interest. Cronbach’s alpha is widely believed to be an indicator of internal consistency (Field, 2009). As a rule of thumb, a measure could be considered reliable if the Cronbach’s alpha value is around .80 (Field, 2009). Finally, inter-rater reliability refers to the degree to which the instrument yields similar results among different assessors; in other words, it explains the level of agreement among different raters of the instrument. The instruments reviewed in this study reported relatively high Cronbach’s alpha values in their corresponding publications, which implies that these measures have good levels of internal consistency reliability. However, it appears that only Cronbach’s alpha values were reported as indicators of good reliability in those publications, which can be insufficient. Indeed, the authors could have done more in terms of reporting the test-retest reliability as well as the inter-rater reliability of the instruments. On a related note, some scales developed outside of academia may not have undergone such rigorous testing of reliability (and validity); thus, the publishers of such instruments need to provide evidence that the scale is both reliable and valid, and that such measures are psychometrically acceptable (Fletcher and Robinson, 2014). Given that employee engagement has attracted a lot of attention from HR practitioners, it is imperative that these psychometric concerns be addressed if we are to develop projects or initiatives aimed at raising engagement levels of employees in the most effective and efficient way. EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 14 Validity The engagement research has been inundated with inconsistent operationalizations and measurements, resulting in confusion as to whether the construct is both conceptually and empirically different from other constructs (Albrecht, 2010; Christian, Garza, and Slaughter, 2011; Macey and Schneider, 2008; Truss, Delbridge, Alfes, Shantz, and Soane, 2014). In contemplating which engagement instrument to use, interested researchers and practitioners need to take into account three major types of validity (Fletcher and Robinson, 2014). First, ‘content validity’ is concerned with the extent to which the measure captures the construct it is intended to measure. Kahn (1990) argued that personal engagement represents a state, in which employees expresses themselves “physically, cognitive, and emotionally” in their work roles (p.692). Engagement, therefore, “should refer to a psychological connection with the performance of work tasks rather than an attitude toward features of the organization or the job” (Christian et al., 2011). Second, ‘convergent validity’ refers to the extent to which the construct is statistically correlated with other similar constructs. Finally, ‘convergent validity’ is concerned with the extent to which the engagement construct is “statistically distinct from other similar, yet different constructs” (Fletcher and Robinson, 2014, p.280). A measure such as the GWA has been heavily criticized for not conforming to Kahn’s conceptualization of engagement (content validity) (Christian et al., 2011). Instead of measuring state, as Kahn (1990) would argue, the GWA focuses on various work conditions, particularly job characteristics such as rewards, feedback, task significance, and development opportunities (Christian et al., 2011; Fletcher and Robinson, 2014; Macey and Schneider, 2008). As Macey and Schneider (2008) put it, the results from the GWA survey data “are used to infer that reports of these conditions signify engagement, but the state of engagement itself is not assessed” (p.7). EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 15 The validity of the UWES – one of the most widely used engagement instruments around the world – has also been under a lot of scrutiny (Saks and Gruman, 2014). Rich et al. (2010, 623), for instance, argued that the UWES includes items that “confound with the antecedent conditions” proposed by Kahn (1990) – particularly items that ask for respondent perceptions of meaningfulness and challenge of work – and thus do not precisely measure engagement as originally conceptualized by him. Similarly, Saks and Gruman (2014) argued that one item of the UWES’ dedication scale – “To me, my job is challenging.” – seems to overlap with some engagement predictors such as autonomy or skill variety. In addition, some of the items of the vigor scale are very similar to items measuring other constructs such as job satisfaction and commitment. Cole et al. (2012) also maintained that there have been questions over the issue of “construct redundancy” between engagement and burnout (p.1576). Cole et al. (2012) employed meta-analytic techniques to attempt to assess the extent to which job burnout and employee engagement are “independent and useful constructs”, and found that “construct redundancy” is a major challenge for understanding and advancing research on burnout and engagement (p.1576). They maintained that the UWES is, based on their findings, empirically redundant with the MBI. They also suggested that engagement researchers should avoid treating the UWES as an instrument that measures a distinct and independent construct, and that more effort vis-à-vis the conceptualization and operationalization of engagement is needed if we are to avoid further confusion and advance our understanding of the engagement phenomenon. It is important to note that our discussion focuses largely on the GWA and the UWES because of their ubiquitous use and because the other instruments have rarely been used elsewhere, and in most cases used only in one study (Saks and Gruman, 2014). Nevertheless, EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 16 there are also validity concerns with other instruments. For instance, James et al. (2011) only reported the face validity of the engagement scale in their publication. The authors claimed “the eight items in the scale, in terms of face validity, measure the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects of engagement” (James et al., 2011, p.182). However, items such as “I would like to be working for Citisales one year from now” and “Compared with other companies I know about, I think Citisales is a great place to work” may measure one’s commitment to the organization and not necessarily fully capture the cognitive aspect of engagement. The issue of ‘discriminant validity’ – whether engagement is simply ‘old wine in a new bottle’ – has also been a major concern for engagement researchers. Some scholars have argued that there is a lot of similarity between engagement and other well-established constructs such as job satisfaction, commitment, and job involvement, whereas others disagree and have found that engagement is a “novel and valuable” concept (Fletcher and Robinson, 2014, p.280). Clearly, more research is needed for us to advance our understanding of the construct and recognize the extent to which engagement is of value to HRD theory and practice. Limitations, Conclusion, and Implications for Future Research and Practice Our review of the literature is limited in several ways. First, there are various other engagement instruments that we did not review in this study, mainly because they exist outside the public domain and are not accessible. Second, there are a number of assessment criteria that we were not able to examine. For example, instrument feasibility (how difficult/convenient it is for responders as well as administrators). This omission is mainly due to the fact that such information is not presented in the instrument publications or that information associated with these other criteria is discussed in a very arbitrary and inconsistent manner by the authors of the publications. EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 17 Despite the limitations, we believe that this study provides useful insights to engagement scholars and practitioners with regard to what scales are available, what their properties are, and how they have been used. Our review illustrates that while various instruments have been developed to ‘measure’ engagement, not all scales have the same theoretical underpinnings or methodological rigor. In addition, certain scales (e.g. UWES, Job Engagement Measure) have been used and cited more frequently than others. It is important, therefore, that engagement scholars and researchers carefully review each instrument’s properties and methodological soundness before selecting an instrument to use for their research. Our review also offers a number of implications for both research and practice. First of all, it seems clear that all the instruments reviewed here require more rigorous testing. Indeed, scale development is an iterative process (Hagen and Peterson, 2014); thus, more evidence of validity and reliability for the scales is needed. In addition, given the popularity of the engagement construct in many different countries, scholars and practitioners should pay specific attention to the appropriateness of the scales before applying any of them in a cross-cultural context. Needless to say, more attempts to validate the scales in non-Western contexts are needed. Third, the inconsistent definitions and theoretical underpinnings used by the developers of each scale could be a cause for concern. Therefore, scholars and practitioners need to review the information about the development of various scales to see which would fit well with their researcher questions and topics. EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 18 References ALBRECHT, S. L. (2010). Handbook of employee engagement: Perspectives, issues, research, and practice, MA, Edward Elgar Publishing. CHRISTIAN, M. S., GARZA, A. S. and SLAUGHTER, J. E. (2011) Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64, pp. 89-136. COLE, M. S., WALTER, F., BEDEIAN, A. G. and O’BOYLE, E. H. (2012) Job burnout and employee engagement: A meta-analytic examination of construct proliferation. Journal of Management, 38, pp. 1550-1581. FIELD, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS, Thousand Oaks, California, Sage. FLETCHER, L. and ROBINSON, D. (2014). Measuring and understanding engagement. In: TRUSS, C., DELBRIDGE, R., ALFES, K., SHANTZ, A. and SOANE, A. (eds.) Employee engagement in theory and practice. New York: Routledge, pp. 273-290. HAGEN, M. S. and PETERSON, S. L. (2014) Coaching scales: A review of the literature and comparative analysis. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 16, pp. 222-241. HARTER, J. K., SCHMIDT, F. L. and HAYES, T. L. (2002) Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A metaanalysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, pp. 268-279. JAMES, J. B., MCKECHNIE, S. and SWANBERG, J. (2011) Predicting employee engagement in an age-diverse retail workforce. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32, pp. 173-196. KAHN, W. A. (1990) Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. The Academy of Management Journal, 33, pp. 692-724. KAHN, W. A. (1992) To be fully there: Psychological presence at work. Human Relations, 45, pp. 321-349. KIM, W., KOLB, J. A. and KIM, T. (2012) The relationship between work engagement and performance: A review of empirical literature and a proposed research agenda. Human Resource Development Review, pp. MACEY, W. H. and SCHNEIDER, B. (2008) The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1, pp. 3-30. MASLACH, C. and LEITER, M. P. (1997). The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it, San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass. MAY, D. R., GILSON, R. L. and HARTER, L. M. (2004) The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77, pp. 11-37. EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 19 RANA, S., ARDICHVILI, A. and TKACHENKO, O. (2014) A theoretical model of the antecedents and outcomes of employee engagement. Journal of Workplace Learning, 26, pp. 249-266. RICH, B. L., LEPINE, J. A. and CRAWFORD, E. R. (2010) Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53, pp. 617-635. ROTHMANN, S. (2014). Employee engagement in a cultural context. In: TRUSS, C., DELBRIDGE, R., ALFES, K., SHANTZ, A. and SOANE, A. (eds.) Employee engagement in theory and practice. New York: Routledge, pp. 163-179. RURKKHUM, S. and BARTLETT, K. R. (2012) The relationship between employee engagement and organizational citizenship behaviour in Thailand. Human Resource Development International, 15, pp. 157-174. SAKS, A. M. (2006) Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, pp. 600-619. SAKS, A. M. and GRUMAN, J. A. (2014) What do we really know about employee engagement? Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25, pp. 155-182. SCHAUFELI, W. B., SALANOVA, M., GONZALEZ-ROMA, V. and BAKKER, A. B. (2002) The measurement of engagement and burnout: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, pp. 71-92. SHIMAZU, A., SCHAUFELI, W., MIYANAKA, D. and IWATA, N. (2010) Why Japanese workers show low work engagement: An item response theory analysis of the Utrecht Work Engagement scale. BioPsychoSocial Medicine, 4, pp. 17. SHIMAZU, A., SCHAUFELI, W. B., KOSUGI, S., SUZUKI, A., NASHIWA, H., KATO, A., SAKAMOTO, M., IRIMAJIRI, H., AMANO, S., HIROHATA, K. and GOTO, R. (2008) Work engagement in Japan: Validation of the Japanese version of the Utrecht work engagement scale. Applied Psychology, 57, pp. 510-523. SHUCK, B., REIO, T. G. and ROCCO, T. S. (2011) Employee engagement: An examination of antecedent and outcome variables. Human Resource Development International, 14, pp. 427-445. SHUCK, B. and WOLLARD, K. (2010) Employee engagement and HRD: A seminal review of the foundations. Human Resource Development Review, 9, pp. 89-110. SOANE, E., TRUSS, C., ALFES, K., SHANTZ, A., REES, C. and GATENBY, M. (2012) Development and application of a new measure of employee engagement: the ISA Engagement Scale. Human Resource Development International, 15, pp. 529-547. TRUSS, C., DELBRIDGE, R., ALFES, K., SHANTZ, A. and SOANE, A. (2014). Employee engagement in theory and practice, New York, Routledge. EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT INSTRUMENTS 20 WOLLARD, K. K. and SHUCK, B. (2011) Antecedents to employee engagement: A structured review of the literature. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 13, pp. 429-446.