PP11 Heat Networks (PDF 226KB)

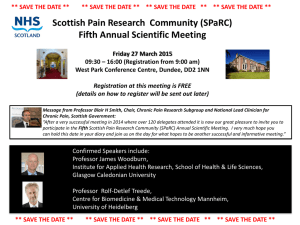

advertisement

Main Issues Report Addendum 2014 Position Paper 11 Heat Networks 1. Introduction 1.1 The need to heat and cool spaces is increasingly being recognised as one of the largest contributors to energy use and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the built environment. Modelling has suggested that in Scotland, heating spaces and heat use in industrial process accounts for over 44% of all energy consumption and 47% of Scotland’s total GHG emissions. Considering that heat alone is responsible for nearly half of GHG emissions, it is therefore a logical step to address the problem of energy efficiency in heat to achieve larger sustainability and carbon reduction goals. The Scottish Government has consequently begun to develop an emerging policy on heat, emphasising the need for “decarbonisation of heat” in Scotland, with heat mapping and heat networks as key components to deliver decarbonisation. The new Scottish Planning Policy (SPP), published in June 2014, is amongst the first of finalised policies that promotes heat efficiency. 1.2 The purpose of this Position Paper will be to understand the full requirements of Aberdeenshire Council’s Local Development Plan (LDP) in light of emerging national and regional policies on heat. It will seek firstly to understand the background to heat mapping and heat networks, exploring the national legislative and policy context that has led to the creation of this policy. It shall then explore the position taken in the current Scottish Planning Policy, and the Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Plan (SDP) before considering the current position on heat promoted by Aberdeenshire Council and the existing LDP. Finally, this Position Paper will draw on the above information to produce a series of recommendations for consideration in the Main Issues Report addendum, to be published in August 2014 that will inform the policy content on heat for the next LDP in 2017. 2. National Policy Context 2.1 The need for a review of the existing policies on heat derives from changes that have occurred at the national level. Although the 2010 SPP considered heat (as part of its policies on Climate Change, Town Centres, Renewable Energy and Waste policies), little specific guidance was made. Instead, references were made to heat in regard to carbon reduction targets and as a consideration in new developments, though the content was non-specific and generalised. The 2014 SPP promotes a fuller heat policy that comprises of both heat mapping and supporting the development of heat networks. As touched upon briefly above, the underlying reason for creating a new policy on heat derives from the need to address climate change. While there is no need to discuss climate change in full in this paper, it is still worthwhile exploring this topic briefly as part of the background to the heat policies that are currently emerging from the Scottish Government (a full discussion has been taken in Position Paper on Climate Change produced for the previous Main Issues Report). 2.2 Both the UK and Scottish Governments accept the scientific consensus on climate change and its anthropogenic sources. In Scotland, it has led to the Government adopting sustainability as a primary purpose, which is “to make Scotland a more successful country, with opportunities for all to flourish, through increasing sustainable economic growth”. A central objective of this strategy is to transition Scotland into a “low carbon economy”. The Scottish Government (2011) argues that long term economic growth can only be achieved through promoting environmental sustainability and delivering a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. As part of this move to a low carbon economy, the Scottish Government has pledged to invest in initiatives to improve the energy efficiency of Scotland’s housing stock and to tackle fuel poverty. This fits into the broader strategic purposes of the Government Economic Strategy to achieve economic growth and reduce emissions, whilst also achieving specific social goals that will contribute to the future economic resilience of Scotland. 2.3 Legislatively, the drive for heat mapping and heat networks helps to contribute towards the Scottish Government’s targets to reduce emissions as set out in the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009. This Act set some of the most ambitious emissions and carbon reduction targets seen globally. The Act sets out that GHG emissions must be reduced by 42% by 2020 and by 80% by 2050. From a planning perspective, there is an obligation for all planning authorities to contribute to sustainable development through the Planning etc. (Scotland) Act 2006. This includes policies in all Local Development Plans to deliver both climate change mitigation and adaptation as part of a wider drive for sustainable development. 2.4 To meet these ambitious targets requires both short-term and long-term actions across all sectors of the Scottish economy and Scottish society. Heat has been specifically targeted for action by the Scottish Government due to the high energy demand and high GHG emissions that are produced through its generation. Figure One below shows the total final energy consumption in Scotland, where it can be seen that heat is the largest consumer of energy, larger than transport and electricity production combined. The Scottish Government definition of heat is broader than just keeping homes and offices warm; it also includes energy to cool properties, to produces hot water, to cook food, to cool food, and to manufacture goods in industrial processes. Of the 55% of energy consumed in Scotland for heating, 40% is consumed domestically and 60% in industrial processes and the commercial sector. Figure One: Total final energy consumption in Scotland, 2011 2.5 As shown in Figure Two, energy supply and production is the largest contributor to GHG emissions in Scotland in 2012. As heat is the largest consumer of energy in Scotland, there is a clear need to tackle inefficiencies in heat production and to reduce the amount of GHG emissions produced. Energy supply is also followed by residential and business and industrial processes which also contribute high proportions of GHG emissions. Again, a proportion of these emissions will be attributable to heat production. A particular inefficiency identified by the Scottish Government pertains to heat supply. In Scotland, heat is not bought and sold as a commodity, unlike many other European countries. Rather, electricity or fuels (such as gas, oil or solid fuels) are bought and on-site appliances are used to provide heating or cooling, such as boilers, kilns, furnaces, electrical heaters and ventilation systems. A 2009 report by Pöyry Energy for the UK Department for Energy and Climate Change found that district heating carbon savings were greater for all types of district heating networks than traditional individual boiler systems, or alternative technologies (e.g.) solar thermal heating and air heat source pumps. Therefore if a mix of alternative sources of heat can be used, the total energy demand from carbonbased fuels can be reduced and lead to a significant reduction in the GHG emissions from energy production. Figure Two: Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, 2012 (Values in MtCO2e) 2.6 As well as the environmental benefits of heat networks, there are also social benefits that may be derived from the use of heat networks. It was found in Aberdeen City Council that buildings connected to district heating schemes have seen a reduction in fuel bills by up to 50 per cent. In addition, there is the added benefit of energy security and independence that comes from a wider energy mix and more efficient use of resources. This may help build the overall resilience of communities in response to the diminished supplies of finite fossil fuels in the future. However, the Pöyry report for the Department for Energy and Climate Change found that less than 2 per cent of the UK’s heat demand was provided by district heating, compared with other European countries where demand was much higher, with Finland meeting 40% of heat demand through district heating, and 60% in Denmark. Clearly then, there is great scope for the use of district heating in the UK. 2.7 In light of the social and environmental benefits associations with heat networks, the Scottish Government has created a vision for the heat industry in Scotland. This vision is: “A largely decarbonised heat system by 2050, with significant progress made by 2030. An ambition which will be realised through a number of means, reducing heat loss, increasing heat generation efficiency through systems such as district heating (where appropriate) and including renewables, An ambition, based on the fundamental first principles of keeping demand to a minimum, most efficient use of energy, recovering as much “unused excess” heat as practically possible, and at least cost to consumers.” 2.8 Central to achieving this vision is the concept of the heat hierarchy. The heat hierarchy (Figure Three) sets out the increasing priorities for achieving a decarbonised heat system in Scotland by 2050. The first priority is to reduce the need for heat. This can be achieved by the suitable insulation, taking advantage of passive heating and cooling and through behavioural change. The second priority is to supply heat efficiently. This can be achieved within buildings (with low temperature radiators) and between buildings with district heat supplies. Finally, the last priority is to use renewable and low carbon heat sources to deliver low carbon heat efficiently. While planning system may have some input into the first priority (e.g. higher energy efficiency standards for new buildings or energy efficiency measures in listed buildings or conservation areas) it is likely that the main area that planning can make a difference within the heat hierarchy is by encouraging heat networks in the second and third priorities. 2.9 The Scottish Government’s (2013) “Outline for a Draft Heat Vision” makes it clear that to pursue this vision for heat will require “holistic” and “cross-cutting” actions to achieve each of the priorities. This includes utilising UK and Scottish Government grants and financing schemes for both domestic and non-domestic energy use, providing advice and also supporting retrofitting of existing housing stock. More relevantly for Aberdeenshire Council’s Local Development Plan is the need to build new housing stock to very low carbon standards. Additionally, there is also a need to implement mapping to understand how heat is distributed spatially – where it is produced and where it is needed. There is also a need to understand and map fuel poverty to allow a more socially sustainable approach to be taken to match the environmentally sustainable decarbonisation approach. Finally, the Scottish Government also emphasises the need for more efficient district heating approaches and micro-generation. Figure Three: The Scottish Government’s Heat Hierarchy 3. Scottish Planning Policy 3.1 SPP 2014 has made decarbonising of heat a national priority for the planning system and is the main pathway through which the Scottish Government’s heat policies are promoted in planning. SPP expects that every planning authority to contribute towards the Scottish Government’s heat priorities. The priorities for the local planning authorities regarding heat as set out in SPP are summarised below in paragraphs 3.2-3.5. These are also supported by the objectives of the National Planning Framework 3, which highlights the potential for developing heat networks as part of a more decentralised pattern of energy generation and supply in the preparation of development plans. 3.2 SPP states that Local Development Plans should use heat mapping to identify the potential for co-locating developments with a high heat demand with sources of heat supply. The following should be identified on the heat maps. Sources of heat supply may include: Harvestable woodlands; Sawmills producing biomass; Biogas production site; Heat recoverable from mine waters, aquifers and other bodies of water; Heat storage systems; Geothermal heat; and Developments producing unused excess heat. Sources of heat demand may include: High density developments; Communities off the gas grid; Fuel-poor areas; Anchor developments such as schools, hospitals and leisure centres; and Heat intensive industries. 3.3 SPP also states that Local Development Plans should support the development of heat networks in as many locations as possible. Initially, this includes supporting the development of carbon-based fuel powered heat networks if they can be converted to run on renewable or low carbon sources of fuel in the future. 3.4 Local Developments Plans should also identify where heat networks, heat storage and energy centres exist. Local Development Plans should identify where these may be appropriate and include policies for their implementation. Local Development Plans may include policies to require new development to include infrastructure for immediate or future connection to heat networks. This includes safeguarding pipeworks to the curtilage of development and within development sites. 3.5 Finally, SPP also states that where heat networks are not viable, micro-generation and heat recovery technologies for individual properties should be supported. 3.6 What may be concluded from the above paragraphs is that the Scottish Government envisions a threefold role that all planning authorities should fulfil. Firstly, the planning authority must map heat, focussing on demand, supply, fuel poverty and existing heat networks. Secondly, the planning authority must support the development of new and existing heat networks, by encouraging their inclusion within new developments through policy, and by safeguarding the required pipework infrastructures. Finally, the planning authority must be supportive of alternatives where heat networks are not appropriate. 3.7 This is supported by the planning note “Planning and Heat” which sets out opportunities for the use of heat maps and networks at different stages in the planning process. Figure Four below shows potential heat mapping components identified in “Planning and Heat”. For development plan policy it specifically suggests developing policy which supports the development of heat networks and heat from renewable sources and to develop policies which encourage proposed development to either connect to existing or heat distribution infrastructure or to be designed so they are capable of becoming so in the future. This mirrors the policies in SPP. For supplementary guidance, it specifically states that it should provide detailed guidance to support the consideration of heat related proposals including locating energy centres to fit with more effective layouts for homes and mixed-communities, handling noise and pollution control, and designing-in heat infrastructure required for district heating, such as thermal storage towers. Figure Four: Potential Heat Mapping Components 3.8 SPP policies on heat also sit within the wider policy group “A Low Carbon Place”, which aims to promote a low carbon economy and reduce GHG emissions. This includes the overarching need to reduce emissions and energy use in new buildings and from new infrastructure by enabling development in appropriate locations that contribute to energy efficiency, heat recovery, efficient energy supply and storage, energy and heat from renewable sources and energy and heat from non-renewable sources where GHG emissions can be significantly reduced. This policy context should also be considered in development of heat networks. SPP also expects that development plans should seek to ensure an area’s full potential for heat from renewable sources is achieved with regard to environmental, community and cumulative impact considerations. In regards to this, the Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Plan (SDP) will be expected to set this strategy. It is therefore important when setting out a position for Aberdeenshire Council to consider not only the position taken in SPP, but also what stated in the SDP. 4. The Strategic Development Plan 4.1 The Aberdeen City and Shire SDP was approved by Scottish Ministers on the 28th of March 2014 and subsequently replaced the Structure Plan. Although predating the publication of the SPP in June 2014, the SDP does make reference to heat mapping and networks. The issue of heat is first addressed in the objectives section of the SDP when it sets out its vision for Sustainable Development and Climate Change in the region. The topic is part of a wider vision to encourage energy efficiency in new and existing developments. Paragraph 4.7 of the SDP states: “All new developments must be designed and built to use resources more efficiently and be located in places where they have as little an effect on the environment as possible… developers will need to examine the scope for including combined heat and power schemes when preparing larger development proposals”. Paragraph 4.9 of the SDP also addresses the issue of energy supply, stating: “We also need to tackle the supply of energy during the plan period. This will involve increasing the supply of heat and power from renewable sources and reducing emissions of climate-change gases from existing power stations… there is considerable potential in … energy from waste... biomass, as well as ground, water and air source heat pumps. A more balanced mix of renewable energy sources will be needed if we are to meet our renewables targets.” 4.2 The SDP also addresses the role of heat when choosing suitable sites for waste treatment developments, highlighting that the “prospect of using any heat or electricity generated by the process” is an important factors for consideration. Finally, the SDP focuses on the role of masterplanning and supplementary guidance to promote heat, advocating the “use [of] master planning (and supplementary guidance) to consider the possible scope of combined heat and power schemes to contribute towards using energy more efficiently and in reducing the amount of energy used overall”. 4.3 The scope of the vision on heat in the SDP are more limited than in SPP and this is likely due to the fact that the proposed SDP predated the publication of draft SPP by a number of months. The SDP does, however, provide a clear vision regarding the location of waste to energy/heat plants and it does make recommendations regarding diversifying energy sources that are in line with the heat hierarchy set out in SPP. Further to this, the SDP sets the question of heat in the wider context of energy efficiency as part of its sustainability and climate change objectives. This provides a natural setting for this policy as it fits into the priorities of the heat hierarchy as shown in Figure Three above, which prioritises efficiency and reducing the need for heat before alternative energy supply sources. The SDP guidance on heat fits well with the approach taken by the Scottish Government, who also place their policy on heat within the overall planning outcome of “a low carbon place” which tackles the problem of carbon emissions and climate change adaptation. Therefore it is a logical conclusion to include any policy or supplementary guidance within policies addressing climate change and carbon reduction. 5. Local Development Plan 5.1 The existing 2012 Local Development Plan does not contain specific guidance on heat networks or heat mapping. It is therefore necessary to consider new policies to be added to the next local development plan to fulfil the expectations of the SPP. Despite this, Aberdeenshire Council has already made some moves towards decarbonising heat and establishing heat networks in the area. In their response to the consultation to the Scottish Government’s Draft Heat Generation Policy, Aberdeenshire Council highlighted their involvement from the outset of the Scottish Heat Map project, and they also highlighted the efforts that have been made by the Council in pioneering the promotion of biomass heating in the North East of Scotland. The previous Main Issues Report (MIR) recognised this policy gap and sought to close it with a policy on climate change. These topics were discussed as Main Issue 1 (a new policy for climate change), Main Issue 6 (other renewable energy developments) and Main Issue 9 (carbon neutrality in new developments). 5.2 The Position Papers for these MIR questions (published in 2013) previously considered the heat hierarchy and the scope for district heating in the Council area. It was highlighted in the Renewable Energy Position Paper that there has already been limited development of heat networks in Aberdeenshire, with small scale developments in Methlick, on the Haddo Estate and at Hill of Banchory, to which over 100 houses and some business units have connected. It is noted in this paper that although there are some successful district heating networks in Aberdeenshire, there are limitations to their successful use throughout the area, as district heating networks are most efficient in high-density urban areas. While it is supported in the Pöyry (2009) report that efficiency is greater in higher density developments, it is also worth noting that the Scottish Government heat map shows that the areas of greatest heat demand in Aberdeenshire are within the larger settlements. The scale and size of these settlements may allow further scope for the development of networks within these settlements than previously thought. Furthermore, SPP makes no reference to density in the heat policy, and states that heat networks should be supported “in as many locations as possible”. The implication of this is that heat networks should be considered in all locations, regardless of density. Higher density areas and developments remain logical locations however, and larger developments particularly should consider the use of heat networks. 5.3 The position paper on renewable energy also has set out the policy recommendations for district heating and heat and power from biomass. The paper recommends that the consideration of feasibility of district heating should be addressed as part of the meeting emissions reductions targets as part of the carbon reductions targets set in the Carbon Neutrality supplementary guidance (SG LSD 11 currently, but proposed in the MIR to be moved to the Climate Change and Carbon Reduction policy). Only where district heating is not feasible would an alternative approach to heating, such as through micro-generation, be approved. It is argued that this approach would accord with national policy and would give adequate scope for the proliferation of the number of district heating schemes and allow possibilities for the expansion of new and existing schemes into neighbouring development where possible. Biomass is also addressed in this policy, where as part of the Other Renewable Energy supplementary guidance (currently SG RD 3, proposed to be moved to the Climate Change and Carbon Reduction policy). Biomass is just one potential source of energy for district heating networks and therefore it is not necessary to make changes to the biomass policy. It was also argued in the Position Paper that, although there are currently ongoing heat-mapping exercises in Aberdeenshire, there is currently not a great enough evidence base to make heat networks mandatory based on this data (for example, we know where heat is generated, but we do not know if the owner is willing to supply the heat for other users). 5.4 The conclusion of the position paper was that heat networks should be encouraged in large-scale developments, but not made mandatory, and that the LDP should require developers to “examine” and “consider” the inclusion of combined heat and power schemes in new developments. While this is noted, it may not entirely fulfil the requirements of the new heat policy in SPP. For example the Position Paper suggests that only larger developments should consider heat networks (in line with SDP). SPP, however, wishes heat networks to be “supported in as many locations as possible”, with no mention made regarding the scale of development. It may therefore be concluded that this includes all development – local, major and national. Furthermore, the SPP is supportive to the development of carbon-based fuel powered heat networks if they can be converted to run on renewable or low carbon sources of fuel in the future. The position paper makes no recommendation regarding this; however, the LDP must take this into consideration. The recommendations in the position paper do not fulfil the need to consider future connection to heat networks and policies should be made in the LDP to support the installation of appropriate infrastructure. Also, the position on heat mapping does not recommend its inclusion in the plan. Again, the SPP takes a differing view, stating that LDPs must include heat mapping and consider this when making appropriate policies and development management decisions. It is therefore clear that, although the recommendations would partially fulfil the requirements of SPP, further policy guidance will need to be made in the LDP, particularly in regard to heat mapping and heat infrastructure requirements in new developments. 6. Conclusions and Recommendations 6.1 This paper has sought to consider the issue of heat alone and has studied national, regional and Aberdeenshire Council documents to do so. Based on the above information, it is clear that changes must be made to Aberdeenshire Council’s current position on heat mapping and heat networks in the LDP. This must take into account national level policies, as pursued through SPP, and also regional level policies, as stated in the Aberdeen City and Shire SDP. The issue of heat was considered previously in the Position Papers published for the previous MIR. However, these papers only gave minimal consideration to the issue of heat as part of wider policy groups and did not consider the issue of heat as an individual topic. This reflects the policy context at the time of publication, which was prior to SPP 2014. While the recommendations in the Position Papers would partially fulfil the requirements of the new SPP, it was found that new policies will be required to ensure the LDP reflects the heat policy in SPP. 6.2 While new policies will be required, differing approaches may be taken. These options are present below: Option One: As the issue of heat networks has been considered and consulted upon as part of Main Issues 1, 6 and 9 of the previous MIR, it is not considered appropriate or necessary to create a separate policy on heat mapping and heat networks. Instead heat mapping should be incorporated into the Climate Change policy text that was proposed and supported in the previous MIR consultation. A map showing an indicative overview of heat demand and supply should also be provided in the plan and referenced in the policy text, as required by Scottish Planning Policy. As this is a dynamic data set and one proposed to increase in accuracy over time, details of how to access up-to-date heat mapping data should also be given. Analysis of Scottish Government heat map data will be made to allow the Local Development Plan to identify where heat networks may be appropriate. Heat networks will be supported through supplementary guidance on Carbon Neutrality in New Development, under the Climate Change policy. As proposed in the 2013 MIR, the supplementary guidance will include a requirement for all major developments to assess the feasibility of providing district heating infrastructure as part of the energy statement. This will include infrastructure for generation, supply, connection and distribution of heat. However, this policy should also be expanded to encourage assessments of the feasibility of district heating in smaller scale developments, particularly where they are located in areas identified as being potentially appropriate for heat networks. In the context of SPP, major development sites are considered to be locations where district heating may be appropriate, as are developments located close to suppliers of marketable heat. To encourage a realistic market for heat networks to develop, it will be required that all new major developments provide pipeworks within the curtilage of development for connection to heat networks (whether these currently exist or could be provided in the lifetime of the buildings) unless there are clear reasons why this should not be done. This will be encouraged in smaller developments also. Pipeworks are likely to consist of high pressure water pipes at a size and scale that will allow full amenity for the occupiers of the development. In line with the conclusions drawn in the Issues and Actions papers from the previous MIR, it will not be mandatory to install new district heating facilities, or to connect to existing networks, however, where it is shown these are feasible, it will be encouraged that new developments utilise heat networks to meet carbon neutrality requirements. Finally, Micro-generation and heat recovery technologies will be promoted in areas where heat networks are not considered appropriate currently. Carbonbased fuel powered heat networks will also be supported if they can be converted to run on renewable or low carbon sources of fuel in the future and show a net reduction in GHG emissions or energy use than individual heating systems. Option Two: A separate Heat Policy can be made or a separate supplementary guidance may be made on heat as part of the Climate Change policy. These would include policy on all aspects of heat, including heat mapping and supporting heat networks. However, these options are not considered viable as it may lead to duplication of existing policies, and may also risk diluting the overarching carbon reduction purpose of this policy by separating it from the Carbon Neutrality in New Development supplementary guidance. Option Three: It may also be an option to make connection to heat networks, or the installation of new heat networks, mandatory in new developments where considered viable. However, as the heat data set is new and untested, this may be an unrealistic requirement to place on the development industry at this time. 6.3 Option Four: As it is not a statutory requirement, it may be an option not to include any policy on heat mapping or heat networks. However, given the environmental and social benefits that can be derived from heat networks (such as lower fuel bills, greater energy efficiency, increased energy security, lower GHG emissions etc.) it is not considered a favourable option. Furthermore, as the concept of district heating was relatively unchallenged and even supported in the previous MIR consultation, the principle accepting this policy is established and it would be difficult to justify a radical change in policy at this stage without considerable evidence as to why such a policy is undesirable. It is recommended that Option One above should be adopted by Aberdeenshire Council as their Preferred Option with the other options considered for inclusion in the Main issues Report addendum as Reasonable Alternative options. These should be considered and consulted upon before adoption as policies in the LDP. Option One is preferred as it will allow the requirements of the SPP to be fully realised in the next LDP, without dismissing the conclusions drawn from the last MIR. It will also avoid policies being duplicated and, by virtue of being part of the Carbon Neutrality supplementary guidance, the idea of heat networks will maintain their context as a carbon reduction method. By adopting this policy, Aberdeenshire Council will not only fulfil the letter of the policy, but also the spirit of the policy in that it will be both a specific guidance on heat networks and also a carbon reduction policy. It is the recommendation of this policy paper to adopt this approach, subject to consultation with the public and stakeholders. 7. Bibliography: Aberdeen City and Shire SDPA, 2014, Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Plan, Aberdeen, Aberdeen City and Shire SDPA Aberdeenshire Council, 2012, Aberdeenshire Local Development Plan 2012, Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire Council Aberdeenshire Council, 2013a, Main Issues Report 2013 Climate Change Position Paper, Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire Council Aberdeenshire Council, 2013b, Main Issues Report 2013 Renewable Energy Position Paper, Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire Council Aberdeenshire Council, 2013c, Main Issues Report 2013, Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire Council Aberdeenshire Council, 2014, Our Ref: Heat Policy Consultation [Online] May 2014. Available from: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/0045/00455159.pdf [Accessed: 30th July 2014] Department of Energy and Climate Change, 2013, Summary of Evidence on District Heating Networks in the UK, London, Department of Energy and Climate Change Pöyry Energy Consulting, 2009, The Potential and Costs of District Heating Networks: A Report to the Department of Energy and Climate Change, Oxford, Pöyry Energy Consulting Scottish Government, Government 2010, Scottish Planning Policy, Edinburgh, Scottish Scottish Government, 2011, The Government Economic Strategy, Edinburgh, Scottish Government Scottish Government, 2013a, Low Carbon Scotland: Meeting the emissions reduction targets 2013-2027, Edinburgh, Scottish Government Scottish Government, 2013b, Outline for a Draft Heat Vision, Edinburgh, Scottish Government Scottish Government, 2014a, Towards Decarbonising Heat: Maximising the opportunities for Scotland, Edinburgh, Scottish Government Scottish Government, 2014b, Scottish Greenhouse Gas Emissions 2012: An official statistics publication for Scotland, Edinburgh, Scottish Government Scottish Government, 2014c, Planning and Heat [Online] 2014. Available from: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/0042/00423580.pdf [Accessed 30th July 2014] Scottish Government, 2014d, Scottish Planning Policy, Edinburgh, Scottish Government Scottish Government, 2014e, National Planning Framework 3, Edinburgh, Scottish Government