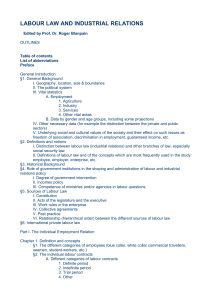

Short note

advertisement