Enhancing support for the mental health of parents and

advertisement

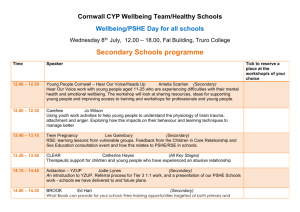

DisabilityCare Australia Enhancing support for the mental health of parents and carers of children with disability A Practical Design Fund Project Delivered by the McCaughey VicHealth Centre for Community Wellbeing, University of Melbourne and the Royal Children’s Hospital. Davis E, Gilson KM, Corr L, Stevenson S, Williams K, Reddihough D, Waters E, Herrman H & Fisher J. Enhancing support for the mental health of parents and carers of children with disability, Practical Design Fund, May 2013 Authors: Dr. Elise Davis Dr. Kim Michelle Gilson Lara Corr Shawn Stevenson Prof. Katrina Williams Prof. Dinah Reddihough Prof. Elizabeth Waters Prof. Helen Herrman Prof. Jane Fisher Stakeholder Reference Group: Kym Phillips, parent Joan Gains, parent Luke Nelson, Youth Disability Advocacy Service Stacey Smith, Medicare Local Gippsland Tina Thomas, LifeLine Carmel Brown, Yooralla Kristen Moeller-Saxon University of Melbourne Dr. Elise Davis, McCaughey Centre, University of Melbourne Lara Corr, McCaughey Centre, University of Melbourne Prof. Katrina Williams, Royal Children’s Hospital Prof. Dinah Reddihough, Royal Children’s Hospital Prof. Helen Herrman, University of Melbourne Dr. Christie Bolch, University of Melbourne Dr. Kim-Michelle Gilson, McCaughey Centre, University of Melbourne Shawn Stevenson, McCaughey Centre, University of Melbourne Funding: DisabilityCare Australia Practical Design Fund Acknowledgements Thank you to all of the parents, health and disability professionals and stakeholder reference group members who shared their valuable time, experience and expertise to develop this resource. Thanks also to Alana Pirrone-Savona who designed and formatted the resources. ii Table of Contents Executive Summary................................................................................................................................. 1 Aims .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology....................................................................................................................................... 2 Key findings ......................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommendations .................................................................................................................................. 2 Background ............................................................................................................................................. 4 What is wellbeing? .................................................................................................................................. 4 The importance of parent and carer wellbeing ...................................................................................... 4 The mental health and wellbeing of carers ............................................................................................ 4 What resources currently exist? ............................................................................................................. 5 Aims and Objectives................................................................................................................................ 7 Methodology........................................................................................................................................... 7 Stakeholder Reference Group............................................................................................................. 7 Ethics approval .................................................................................................................................... 7 Recruitment Strategy .......................................................................................................................... 7 Participants ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Interview Approach............................................................................................................................. 8 Procedure............................................................................................................................................ 8 Resource Development....................................................................................................................... 8 Data Collection and Data Analysis ...................................................................................................... 9 Project Outcomes and Results ................................................................................................................ 9 Interview Participants ......................................................................................................................... 9 Parent and key informant insights into developing the mental health resource ............................... 9 Developing the Mental Wellbeing Resource for Parents and Carers ................................................... 18 Evaluating the Mental Wellbeing Resource .......................................................................................... 19 What was valued? ............................................................................................................................. 20 Resource refinement ........................................................................................................................ 22 Limitations ............................................................................................................................................ 23 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................ 23 Conclusions ........................................................................................................................................... 24 Citations ................................................................................................................................................ 25 Appendices............................................................................................................................................ 28 iii Executive Summary The current disability system places an unreasonable reliance on family carers and one objective of the NDIS is to change that imbalance. The Commission considers that there should be greater assistance for (unpaid) carers through properly funded training and counselling services.(1) Mental wellbeing of parents of children, adolescents and youth with a disability is extremely important to the parent, the child and the whole family. Mental wellbeing is “a dynamic state that refers to individuals’ ability to develop their potential, work productively and creatively, build strong and positive relationships with others and contribute to their community.”(2) While all parents have heightened needs for support during their child’s life, parents and carers of children and young people with a disability experience additional challenges and stressors. These extra challenges are likely to require targeted action to help protect, promote and increase their mental wellbeing. Parents of children with a disability are at risk of poor mental health. There are high rates of clinically significant depressive symptoms (3, 4) with stress, anxiety and poor sleep commonly reported.(5-7) The higher rates of poor mental health are related to stressors such as unmet service needs, the severity of the child’s disability and behavioural difficulties, limited social support and poor family functioning.(8-10) It has been reported that parents and carers of children and young people with a disability often have substantial yet unmet mental health needs.(8, 11) These unmet needs may influence the care they can provide for children with disability and limit their participation in and contribution to social and economic life. It is important that the wellbeing of parents and carers is addressed alongside the wellbeing of their children. In its review of Disability Care and Support 2011, the Productivity Commission recommended that supporting the mental health of parents and carers of people with a disability be recognised and funded as part of DisabilityCare Australia - a major reform that includes the establishment of a National Disability Insurance Scheme.(1) Aims The aim of this project was to produce a practical resource to prepare the disability services workforce to support the wellbeing of parents and carers of children (0-25 years) with 1 disability by raising greater awareness of strategies and activities to promote greater wellbeing. Methodology Interviews were conducted with 20 parents and carers of children, adolescents and young people with a disability; 13 representatives from health and disability organizations; and guidance from our stakeholder reference group. Two resources were produced, including a resource for parents and one for local area coordinators (LACs). The resource was evaluated by 28 parents and health professionals, as well as the stakeholder reference group. Key findings Parents voiced the need for a resource that is specifically targeted towards their wellbeing. They acknowledged many of the existing resources on wellbeing focused on their child’s wellbeing rather than their own. Parents and health professionals recommended that the following was included: o Strategies for looking after yourself o Ways to improve social support o Opportunities for action/self-reflection o Activities and strategies to promote wellbeing o Awareness of what can affect a person’s wellbeing o Barriers to wellbeing o Complexity of respite o Importance of counseling Two resources were produced, which included a Resource for parents about their mental wellbeing, and a Support Guide for LACs to ensure they have a good understanding of the resource and how to use it. Recommendations The resource is evaluated for cultural appropriateness and sensitivity, and as appropriate, adapted and translated for use with parents and carers of different cultural and linguistic backgrounds. 2 LACs receive basic training to ensure the resource is effectively delivered including working with interpreters to discuss issues in the resource. The impact and effectiveness of the resource is evaluated to ensure it is meeting its aims and whether additional steps are needed to support parent and carer mental wellbeing. Consideration of a website or section of a website for parents - collaborating with Raising Children’s Network etc. Other options: smart phone application, online videos etc. The resource is reviewed and updated on an annual or biannual basis. There is a complementary resource tailored to supporting the wellbeing of siblings of children and young people with a disability and their unique circumstances and needs. There is a complementary resource tailored to the needs of parents of young adults with a disability. 3 Background Under DisabilityCare Australia (National Disability Insurance Scheme), local area coordinators (LACs) will be the primary contact for families of children and young people with a disability. LACs will not only focus on the needs of children and young people with disabilities, they will also examine and support the needs of the family. In order for DisabilityCare Australia to support parents and carers to receive the individualised care and support they need, their wellbeing needs to be supported. What is wellbeing? Mental wellbeing is “a dynamic state that refers to individuals’ ability to develop their potential, work productively and creatively, build strong and positive relationships with others and contribute to their community.”(2) The importance of parent and carer wellbeing Raising a child with a disability can place strain on the physical, social and emotional wellbeing of parents and carers. The wellbeing of parents and carers is of high priority given that their wellbeing can affect their capacity to provide quality care (12, 13) and is a risk factor for a number of poor outcomes in the child.(14) A substantial proportion of parents with poor subjective wellbeing consider their health to be of low priority or are reluctant to use services for themselves.(15) It is therefore essential to promote greater awareness and knowledge of the importance of wellbeing in parents and carers. The mental health and wellbeing of carers Research on the mental health and wellbeing of carers consistently shows parents who care for their child with a disability have poorer subjective mental health than other carers. Several studies have shown that mothers and fathers report greater parenting stress and depressive symptoms compared to mothers and fathers of typically developing children.(1618) Research has also documented compromised physical health in parents of children with a disability, with reports of back pain, migraine headaches and digestive complaints.(19, 20) 4 A substantial proportion of the literature has focused on the mother as the primary caregiver of a child with a disability. These studies highlight that mothers have higher levels of chronic stress, depressive symptoms, fatigue as well as poor sleep quality compared to mothers of typically developing children.(12, 13, 19-21) A review of international studies showed that mothers of children with a disability have consistently higher rates of clinically significant depressive symptoms. These ranged from 6 to 49% of participants, with an estimated average of 23.6% experiencing clinically significant depression levels.(3) There are common determinants that have been consistently shown to predict poor mental well-being in parents. Multiple studies support child specific characteristics, which include the severity of the disability, the child’s emotional functioning and behavioural disturbance as significant predictors of high parental stress,(22) poor mental and physical health (9, 23) and poor health related quality of life.(24) Low levels of self-esteem and perceived control are also commonly associated with poor maternal mental health.(8, 25) Other work has shown emotion focused coping and the level of social and family support are significantly related to poor parental wellbeing.(3) In contrast, key predictors of positive mental health have included maternal empowerment or mastery over the caregiving situation and participation in health promoting activities, both of which have positive association with subjective mental health in mothers. Although there is considerable research on the mental wellbeing of parents raising a child with a disability, there are few practical-based educational resources that promote awareness of mental wellbeing in this subsample of caregivers. Such a resource could indirectly impact the mental wellbeing of parents and carers by encouraging them to seek help or to learn more about what they can do to improve their wellbeing. What resources currently exist? In an extensive online search of the mental health and wellbeing resources specifically designed for parents and carers of children and young people with a disability, the results showed that very few resources currently exist. Three resource-related criteria were used in the search: 1) the resource is specifically aimed towards parents and carers of children with disability, 2) the resource has a primary focus on mental health and wellbeing, 3) the resource was available online as a downloadable pdf. One resource was identified as 5 meeting all three specific search criteria. This resource, developed by the Association for Children with a Disability was a 30 page document, titled “Helping You and Your Family: Information, support and advocacy for parents of children with a disability in Victoria” 2nd edition (2009). This was written by parents for parents of children with a disability and contains major themes related to wellbeing such as: disability diagnosis and it’s emotional impact, the emotional ups and downs, your support network, family and friends, and looking after yourself. Outside the specific search criteria, a number of broader resources specifically designed for parents and carers were identified that contained subsections of material on wellbeing and mental health. Common themes included in these subsections were often around: tips on how parents could take better care of themselves (e.g. activities and strategies), access to counseling and the benefits of this, the importance of support groups and friendships, and useful contacts and helplines. For example, the Raising Children Network website provided downloadable information on the feelings associated with parenting a child with disability and tips for how to cope with these. It also contained a large section on information about the impact of disability on family relationships, and the importance of talking to others about your child’s disability. Another resource that contained comprehensive material on wellbeing for parents and carers was within the booklet “Parent to Parent” developed by Deakin University and the Department of Human Services in 2003. This contained a specific chapter titled “Looking after yourself”, which included many perspectives of parents and various strategies around promoting self-care and taking respite. Further parent and carer resources that contained important information on wellbeing within their specific subsections are listed in Appendix 1. In summary, only one resource was identified that was specific to parents and carers on mental health and wellbeing. A number of other resources that contained subsections of material on wellbeing were identified and used to guide resource development in this project. 6 Aims and Objectives The aim of this project was to produce a practical resource to support the wellbeing of parents and carers of children (0-25 years) with disability by raising greater awareness of strategies and activities to promote greater wellbeing. To accompany the practical resource and prepare the disability services workforce, a further aim was to produce a support guide for LACs that will assist them in the delivery of the resource. Methodology Stakeholder Reference Group The stakeholder reference group (SRG) for this project consisted of parents of children with disability and representatives from Youth Disability Advocacy Service (YDAS), Lifeline, Yooralla, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, and the University of Melbourne. The stakeholder reference group provided support with recruitment of participant families and advice regarding design, implementation and development of recommendations gained through evaluation to be incorporated in the final resource. Ethics approval The project received ethics approval from University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 1237362). Recruitment Strategy Parent participants were recruited by a Chief Investigator (CI), a paediatrician at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, Victoria. The CI informed parents and carers of a child or young adult (aged 0-25 years) with a disability about the study and emphasised that neither their relationship with the hospital or their child’s treatment would be impacted by their choice to participate or to not to participate. If participants were interested in the study the contact details were provided to a researcher who contacted the parent or carer to explain the study in detail, receive consent and to arrange a time for the first interview to take place. 7 Professional participants were recruited through existing disability and health contacts, internet searches and recommendations from contacts. Stakeholders were sent an email inviting them to take part in the study, with a consent form to return to the researcher via email or post. If a participant was interested a researcher made contact with the participant to explain the interview process, receive consent to participate and arrange a time for the first interview to take place. Participants A sample of twenty parents and carers of a child or young person (aged 0-25 years) with a disability and thirteen stakeholders from disability and mental health organisations participated in the study. Interview Approach Interviews were performed across two phases of the study: Phase one interviews guided resource development while phase two interviews focused on how well the resource was received by participants and asked for suggestions for further improvement. Phase two interviews took place after a trial period of the resource. The same participants took part in both phases of the interviews. Different interview questions were formed for parents/carers and stakeholders. Questions for parents and carers facilitated the development of a resource designed for them. Procedure Interviews took place over the telephone or in person and participants were provided the opportunity to complete the interview outside of standard work hours. All interviews aimed to take approximately 30 minutes and were conducted by a female research psychologist and a male researcher from the University of Melbourne. Written and informed consent was received from all participants before the interviews commenced. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Resource Development Both resources were developed through a number of steps: 1) background literature reviews on the mental wellbeing of parents and carers who care for a child with disabilities, and on the existing resources that target mental wellbeing for this subgroup of parents and carers; 2) stakeholder reference group meetings; and 3) interviews with carers and 8 stakeholders. A psychologist and parent author were used in the final design and writing of the resource for parents. Data Collection and Data Analysis Interviews were recorded using a digital recorder and the sound file was then transcribed verbatim using an external transcription service. The transcriptions were then subject to thematic analysis by generating codes that were grouped into key themes. Analysis was conducted by two researchers and themes compared and consensus achieved. Project Outcomes and Results Interview Participants Parent participants included 15 mothers and 5 fathers of children aged from 2 to 18 years old. The children had a range of diagnoses including Cerebral Palsy, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Intellectual Disability, Neurodegenerative Disorder, Down syndrome, and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. The professional interview participants included 6 Psychologists, 2 Occupational Therapists, 1 Specialist Nurse, 1 CEO, 2 Family counselors and a Paediatrician. Parent and key informant insights into developing the mental health resource Acknowledge that the Grieving Process is Normal Parents described a range of emotions they felt when their child was first diagnosed with a disability or multiple disabilities. Grief, anger and different ways of ‘processing’ the news were key themes that parents wanted acknowledged and normalised in the resource. “A child being diagnosed with a disability usually has a grieving process associated with it and I think it's quite important for any document that having a grieving process is natural and normal and especially if it's a diagnosis that was delayed or late. And then different people would deal with that grieving process in different ways and then it's okay to grieve.” Richard father of Zac age 11 Health and disability professionals also recognised these strong emotions in parents and 9 described how parents went through stages of grieving associated with their child’s diagnosis/es. They echoed parent’s desires for the resource to acknowledge and normalise common feelings of parents and carers. “…the initial sort of shock and grief when there's a diagnosis for the disability, which might happen straight away or might not happen for a long time and so the grief around that but also at different stages of a child's life that grief is registered in different ways.” Hannah, Psychologist Strategies for Looking after yourself Participants emphasised that information around ‘looking after yourself’ could help to inform their thinking about mental wellbeing. They presented a range of issues that could be addressed in the resource to promote the overall wellbeing of parents and carers of children and young people with a disability. These themes included the promotion of physical as well as mental health and providing tips on what is important for wellbeing. It was felt that parents focus heavily on their children and that their own wellbeing was often overlooked, therefore a section on why looking after themselves is important, for both parents and the children’s outcomes. “An emphasis on how important the carers are for the individual [child or young adult with a disability] and how they should feel good about themselves as well. You never get recognised for that, so just hearing it or you know seeing it, “you're doing a good job,” that's all you need to hear sometimes, "just keep going, you're doing a good job.”” Paul, father of Jack 2 and Nicholas 4 Understanding and acknowledging the complexity of parent and family life was a highly relevant message that needed to be considered throughout the resource. Parents also highlighted the need for important messages that could motivate them to take action. The messages needed to give permission that asking for help and taking time to think about themselves was okay. Parents also mentioned the importance of gentle messages such as “it is okay to do things at your own pace.” Parents emphasised that these messages would have the greatest impact if they came from parents own experiences. 10 “It's really asking for that help and if somebody doesn't help you, then keep asking, go somewhere else and pass it over, give it to somebody.” Alison mother “I found myself burning the candle at both ends and I guess having a resource there for families to say… don't try and do everything at once.” “You need to go and seek help for yourself even if you don't feel that you need it.” Brenda mother of Jack 2 and Nicholas 4 Messages to avoid were also highlighted. They largely pertained to presenting tips or information in a simplistic and directive or ‘telling’ way: “There is no point in telling people, "You've got to look after yourself.”” Lyn mother Health and disability professionals commented that it was important to write ‘without assumptions’ as much as possible to avoid the resource being prescriptive about how a parent should feel. “So I think in anything that's written you just have to be so careful about canvassing all the options and not us making predictions that people feel this now and then they'll feel this ...” Diane Psychologist Emphasise the importance of social support Social support is essential for mental wellbeing and this was well recognised by parents and carers in the study. Support groups were frequently suggested as a source of emotional support and as ways to connect with other parents and families in similar situations: “To me support groups, as in other mothers going through it have been a big help and the parent network to me were my emotional thing.” Mary parent of Sam However, finding the right fit in these social groups was sometimes a challenge and it cannot be presumed that parent support groups are suitable for all parents. Regardless of the common ground concerning their child’s disability type, some parents felt that these groups were not helpful to them and focused too much on disability, in fact, for some 11 parents general community groups were more effective for their mental wellbeing. These natural variations and preferences needed to be captured in the resource. Parents described not only the benefits of connecting with other people socially but also as a source of meaning in helping or supporting other parents of children with a disability. Further, local support groups and those with children diagnosed with similar disabilities were useful in terms of finding out local information and hearing recommendations for services and programs, which could reduce the burden on parents. Provide opportunities for action and self-reflection Several parents suggested that the resource could include an action component as well as information, such as empowerment to make a decision or take the next step concerning their wellbeing. They spoke about helping to shift parents into a proactive stage of thinking. As one parent reflected “I would much rather see something that moved me towards making an action or making a choice or making a decision.” Dani Mother of Alexandre 17 The importance of self-reflection was also emphasised by both parents and health and disability professionals. Parents recommended that a checklist be included in the resource to help parents reflect on their mental health and wellbeing and to promote self-awareness. The checklist should include things for parents to ‘look out for’. “Maybe questions on "Have you cried much today?" or "Are you looking forward to tomorrow?" and those sorts of questions and then maybe lead into "If you feel like this you should maybe be contacting your GP or maybe contact your local gym to start some exercises," those sorts of things.” April mother of Stacey Pathways and flowcharts were also highlighted as user-friendly ways to work through their mental health needs and appropriate strategies for the stage they were at, such as various options for help-seeking and additional support. 12 Activities and Strategies to promote wellbeing Parents recommended a number of strategies for increasing wellbeing that could be included in the resource. Strategies ranged from personal approaches to improving wellbeing to specific activities that could be undertaken. Taking a pro-active approach was described, however they also cautioned that parents allow planning time and keep activities and expectations simple and realistic (often starting out quite small), as to not be discouraged. “Making that list of things to do but at the same time saying to yourself "I don't have to do all of those in one day…" "I'm going to make that phone call and then go out for coffee.”” Jin mother Connecting with family, friends and creating new social circles through volunteering or attending a community activity were mentioned as ideas for parents to try. It was thought that parents should also be prompted to think about or explore joining in activities that they enjoy, make them feel happy, useful or ‘in control’. These activities may be outside of their usual parenting role and even relate to things they used to enjoy in the past. “For me it's been really important to have something outside of that which for me has been painting all these years, fitness recently, but painting because when I've had a good session or whatever it just gives me something outside of that that helps me, it basically feeds me in a different way but it also helps me not be life and death about every little up and down in his health.” Gloria mother Lastly, though it was seen by some as a chore or impossible to accommodate, the importance of physical activity for boosting wellbeing was highlighted by many parents. “I felt like I was getting quite anxious and more low in my moods, less moments of joyfulness and picking up my physical fitness has been really good.” Gloria mother 13 “...a walking group, something that's not just about "let's sit and talk about our problems over a cup of coffee" but let's enjoy a shared common leisure activity that's not just about the disability” Keri mother of Angelina 13 Awareness of what can affect parents’ wellbeing There was widespread belief that the resource needs to convey acknowledgement, be awareness raising and normalise the way having a child with a disability influences parent and carer wellbeing. Emotional health was often compromised during major transitions in the child’s life, however it was recognised that the fluctuation of stress and emotional health was a normal part of living. Parents spoke of having periods of very poor mental health and of being overwhelmed and unable to think clearly and objectively about their situation. “A disability is like a major stressor to everybody and the emotional reaction to that stressor is wide and varied and so the parents are dealing with a lot of this stuff also as well.” Richard father of Zac 7 “...when she was littler I couldn't see past what we were dealing with at home.” Mary mother Parents wanted the resource to acknowledge that the meaning of wellbeing is different for everyone and but regardless to include education about what wellbeing can look like and what the benefits are to working to improving wellbeing. “I think it would be good to list areas of wellbeing because people may not think of some areas, whether it be social, whether it be seeking counselling, whether it be seeking marriage counselling, whether it be thinking about the issues your other children may be facing.” Karina mother 14 It was clear that after acknowledging wellbeing issues parents needed to be shown pathways to action to ensure they have an idea of potential ‘next steps’. “...acknowledgement of being in a difficult place but then that support needs to come through very quickly after that so that the mindset of the person reading it is taken to a positive place and can see a pathway of action.” Kristy mother of Tom 17 Barriers to wellbeing/accepting help A number of barriers prevented parents from acting, seeking and accepting help or support for their mental wellbeing. These included feeling: defensive; unsupported; unsure of the future; isolated; unable to ask for help; like there was insufficient time to spend on self; and the stigma of experiencing poor mental health. It was seen as important for the resource to acknowledge these types of feelings as well as other real and perceived barriers to helpseeking or improving wellbeing. Being on a low income was a very real barrier to promoting wellbeing for many parents. It affected their ability to pay for additional services or engage in leisure pursuits and strained mental health in a variety of ways. “We’re both on Centrelink. So we have very limited sources of income and that limits I think our abilities to seek additional help for ourselves, just certain things that we would love to do or be able to access but we don't have the money to do that.” Erin mother It was often said that asking for help was difficult, even from family. Further, when help was suggested, it was often seen as, or indeed was, unrealistic, given the family context. “It's a bit frustrating if you're told [what to do] and you've got no real way of doing it or some of the options that are given to you like there's cheap or free gym membership Monday mornings or something. You can go to this parents' support group, they're meeting in the pub on a Friday night and you sort of think "Yeah, right, I'm a single parent, what do I do with my children"?” Veronica mother of Charlie 13 15 Complexity of Respite Respite was a complex and highly emotive topic for parents. A variety of barriers to using respite were shared such as discomfort with taking up respite, poor perception of care quality particularly compared with parental care, and parent/family need for respite. It was, however, generally agreed that good quality respite could be very useful in providing parents and carers with a much needed break and opportunity to increase their wellbeing. “So that has been life changing for myself, having the in-home care because I had three children with autism so that is harder than they think. It had saved my marriage in some sense because I actually get time off.” Lyn mother of Warren 2 The complexity of emotion and circumstances surrounding the use of respite needed to be acknowledged and straightforward information about respite opportunities provided. As guilt was a major issue for some parents, giving permission to use respite was seen as essential to the resource. “Absolutely don't feel guilty and you feel grateful instead because I think it is a gift to your family if you can accept the help because you're all going to benefit.” George father of Sarah 17 Importance of Counselling Given the influence of caring for a child or young person with a disability on parents, the importance of gaining extra emotional support through counselling was frequently advocated by participants. Again, giving parents permission to seek this support was important for the resource. “Don't let it build up. Recognise that there's a problem and it's okay to get counselling.” Lori mother of Xavier 4 It was also highlighted that accessing counsellors has its challenges. These included finding the right personal match with a counsellor as well as cost and time barriers. Including partners in counselling was recommended, though often difficult to achieve for a variety of 16 reasons including the partner’s willingness to be involved and the practicality of having both parents unavailable for caring. “I mean if I could I'd add couples counselling but that takes two to tango” and “I think it would be fantastic if it was almost compulsory, not compulsory but if it was made really easy because men tend to be more reluctant."” Lynn mother of Valerie 14 Tone and Format of the Resource Parents underlined that a warm and friendly tone must be taken throughout the resource, and that using a patronising or condescending tone would be a huge limitation. Parents wanted the resource to be encouraging and positive, but to also normalise and validate their stressful experiences and strong emotions. Parents consistently highlighted that the inclusion of parent perspectives would be critical to a meaningful and relevant resource. This included advice and quotes from parents, some of which that normalised the experience and pressures associated with caring for a child or young person with a disability. “...parents talking to each other or passing on their own tips and information would probably be the best way to go. Sort of how someone else in the same situation, how do they do it.” Vicky mother of Simon 13 “...have [quotes/stories] dotted through it "Mary cares for her son who blah, blah, blah and this is her situation." Just little examples. Because I think it makes you feel a bit less alone and more normal.” Karen mother of Chris 14 Parents also described using photos as a way to identify the resource was ‘for them’ and helped them to feel connected with the resource: “...maybe a picture, it doesn't have to be a big one, probably at the beginning somewhere, that would attract my attention "yes, I can identify that this mum, she's ordinary and loving caring type of mum.” Phoebe mother of Jackson 3 17 Professional representatives also expressed the need for the resource to be evidence-based, accurate and reliable in its information. “... accurate and consistent information. So often there's a lot of information that might be out dated or inaccurate.” Simone Psychologist Parents described the need to have information that was in very plain language, and clearly structured with subheadings that they could easily return to. “I guess making something that's also in very plain language that families can understand because sometimes we get caught up in a lot of jargon.” Beth mother of Jordan 4 Overall, reports by parents and professionals about how they would like information to be presented in the resource were consistent with evidence from a study by Mitchell and Sloper (26) on good information practice for parents and carers looking after children with disability. This study identified the need for clearly written, easy to read information that had a chatter manner and reassuring tone (i.e., “It is OK to ask for help”). Developing the Mental Wellbeing Resource for Parents and Carers Based on the perspectives of parents and health professionals, the following areas were included in the resource: What is wellbeing? Why is self-care important? Thinking about your own wellbeing Identifying when you’re not okay How you can improve your wellbeing Avoiding being too hard on yourself Planning time for yourself Taking a break from caring Building social relationships 18 Talking about how you feel Useful resources The Resource was written by the team, and led by a psychologist and a parent of a child with a disability. Developing a Support Guide for LACs Given that the mental health of parents of children with a disability is a sensitive issue that can be difficult to raise and difficult to respond to, our team felt that LACs would benefit from having a support guide for the dissemination of the mental health resource. Key topics covered in this resource guide include: Background on the mental wellbeing of parents and carers What things are related to parents and carers having good mental health? Poor mental health and wellbeing in parents and carers Mental illness When are the most stressful times for parents and carers? Using the Wellbeing Resource Introducing the Resource Trust and listening skills Do’s and Don’ts when discussing the Resource What to do if a parent becomes distressed or needs immediate help? Protecting your wellbeing The content for the Support Guide was based on a few existing resources, including those developed by the R U Okay website and material from clinical psychology resources. Evaluating the Mental Wellbeing Resource During Stage 2 of this project, parents and health professional participants shared their perspectives on the draft resource with a researcher during 28 individual interviews (17 parents, 11 health professionals) that ranged from 5 to 44 minutes in length. They responded to a brief series of questions (see Appendix 2 and 3) to reveal their views on the 19 content and form of the resource and importantly, what they liked or felt could be improved. The findings, featured here in brief, were used to refine resource development and lead to the final resource. What was valued? Overall, participants were pleased with the resource content and tone. Positive feedback focused on sections addressing wellbeing, common emotions, strategies to improving wellbeing and accessing support. The general structure of the resource and the inclusion of fathers were also well received. Wellbeing: Parent, carer and professional participants commented that they liked the definition of wellbeing and that it was a valuable refresher on the subject. They felt it was framed in a supportive and positive way in which parents would be able to connect with. “I was surprisingly moved by it actually. I didn't expect to be, just sort of reading through it, I don't think it told me anything new but it reinforced things I knew that you don't think about. I just felt "oh my God, yes, I forgot about that, that is true.”" Sasha mother of Luke 13 Acknowledging common emotions: Emotions raised in “Think about Your Wellbeing” resonated with participants. Professionals, parents and carers all commented that for many there is a cycle of emotions and sometimes opposing emotions can be felt - pulling a person in opposing directions. “Every part of it resonated with me and this is what I meant when I said to you that I understand all of those feelings, the negative ones as well as the positive ones and I think that we go through that cycle all the time and I think that it's good to recognise that because that's one of the hardest things, for me anyway, to admit that I'm not coping at the time or I don't want to be doing this sometimes and that's a fleeting thing but it certainly is part of it all.” Allan father of Bryony Strategies to improve wellbeing: Parents and carers especially enjoyed the “brainstorm” tips to make time for themselves. Many participants commented that they found it preferable to more prescriptive methods they had encountered in the past. 20 “This point, that it may help you to brainstorm possible activities that could fit into your lifestyle. It's that sort of thing that rather than being prescriptive it's saying "look at what you could possibly do" and then to hear other parents say, so it's more indirect, so other parents say that when I do get to the gym or when I do work it does make me feel better. So it's going about it from that aspect is just much easier to swallow.”” Henrietta mother of Beth 17 Accessing support: Participants liked the information presented on asking for help and respite. Many participants spoke of how they felt when allowing another person to care for their child and how those feelings can be a significant barrier to accessing support. They felt the resource normalized those feelings which would help parents in their journey. Participants stressed the importance of including advice for planning for formal and informal respite in advance to support wellbeing, rather than only in times of crisis. The inclusion of information on Medicare funded programs was welcomed, as participants felt it was crucial for parents and carers to speak to a GP and LAC about the programs that they may be eligible for. They also felt it was important to include the section that highlighted how the need to access support varies widely, depending on parent and family needs. Structure: Many participants noted that because the information shared was presented using a structure of background or introductory information and strategies to improve mental wellbeing accompanied by parent quotes, gave them the feeling of empowerment that they could improve their self-care. “A lot of people are so busy focussing on what they can't do that they do forget about the little things that they do every day and I think that was really important when I read that. That's what I got the most out of this whole thing, that's something that I've learnt through reading this.” Ellen mother of Tom 11 “I really like the "taking time for yourself" because you never do that. You're always last to do anything for yourself and having some recognition that I am important, I am an important link in this chain so if I'm broken then pretty much the chain doesn't work.” James father of Zara 13 21 Including fathers: The inclusion of father specific information was well received. Many mothers and fathers were pleased feeling that the document was supportive of both, irrespective of who is the primary or secondary carer. “It's important that men get support as well. They have to deal with a lot. They have to go out and earn a wage and then when they come home they're exhausted and then they have to still go about their day-to-day tasks of being the father, especially being the father of a special needs child or children for that matter.” Brenda mother of Jack 2 and Nicholas 4 Resource refinement As parents and health professionals had contributed significantly to the content, tone and structure of the resource, their evaluations resulted in only a small number of suggested changes to improve the resource. All suggestions were incorporated into the final resource, or when out of the scope of this project, have been included in the ‘Recommendations’ section at the end of the report for future consideration. Including an introduction on who created the document and where it came from. Interspersing contact information throughout the resource to introduce the service, resource or helpline to the reader. Reinforce that many help lines are there to offer support and reassurance and not only available for crisis. Ensure that parental stress is not implied to simply be the result of having a child with a disability, but rather acknowledge the logistical and other stressors encountered. Care to ensure that emotions described were not too heavy or ‘doom and gloom’ Highlight that GPs and Medicare can cover a range of services, not just counselling or psychology. So it is important to speak to your GP to see if there is a professional who can match with what you would like. Highlight the simplicity of obtaining a mental health plan from the GP to remove that barrier to accessing support. 22 Limitations This resource is based on the perspectives of parents and health professionals that participated in the study and thus needs to be interpreted within that context. Whilst we had a lot of parents of children and adolescents involved in the study, we only had a few parents of young adults involved in the study. Given the complexity of the issues for parents of young adults with a disability, it is recommended that further research is conducted to develop a resource specific for parents of young adults with a disability. Recommendations The resource is evaluated for cultural appropriateness and sensitivity, and as appropriate, adapted and translated for use with parents and carers of different cultural and linguistic backgrounds. LACs receive basic training to ensure the resource is effectively delivered including working with interpreters to discuss issues in the resource. The impact and effectiveness of the resource is evaluated to ensure it is meeting its aims and additional steps that could be taken to support parent and carer mental wellbeing. Consideration of a website or section of a website for parents- collaborating with Raising Children’s Network etc. Other options: smart phone application, online videos etc. The mental wellbeing of parents and carers is routinely discussed and monitored and that data is used to inform additional programs/initiatives to support wellbeing. The resource is reviewed and updated on an annual or biannual basis. There is a complementary resource tailored to supporting the wellbeing of siblings of children and young people with a disability and their unique circumstances and needs. There is a complementary resource tailored to the needs of parents of young adults with a disability. 23 Conclusions The wellbeing needs of parents and carers require greater recognition. Existing research has highlighted that there are high levels of poor mental health and wellbeing in this subgroup of caregivers and that their needs go unnoticed. This can impact the quality of care that they provide for their child or young person with a disability. This study produced an evidence-based resource to be used by LACs working with parents and carers of children and young adults with a disability. The resource aims to encourage awareness and action on the promotion of parent and carer mental health. The resource was developed through: reviewing the academic literature on parent/carer mental health and wellbeing; reviewing current resources targeting parent/carer mental health and wellbeing; seeking the perspectives and opinions of parents and carers and representatives from health and disability organizations; and in collaboration with a stakeholder reference group. 24 Citations 1. Productivity Commission. Disability Care and Support Productivity Commission Inquiry Report. Canberra 2011. p. 91. 2. Beddington J, Cooper CL, Field J, Goswami U, Huppert FA, Jenkins R, et al. The mental wealth of nations. Nature. 2008;455:1057-60. 3. Bailey DBJ, Golden RN, Roberts J, Ford A. Maternal depression and developmental disability: research critique. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2007; 13(4):321-9. 4. Singer GH. Meta-analysis of comparative studies of depression in mothers of children with and without developmental disabilities. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 2006; 111(3):155-69. 5. Grant S, Cross E, Wraith JE, Jones S, Mahon L, Lomax M, et al. Parental social support, coping strategies, resilience factors, stress, anxiety and depression levels in parents of children with MPS III (Sanfilippo syndrome) or children with intellectual disabilities (ID). Journal of Inherited Metabalic Disorders. 2013; 36(2):281-91. 6. Lovell B, Moss M, Wetherell MA. With a little help from my friends: Psychological, endocrine and health corollaries of social support in parental caregivers of children with autism or ADHD. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2012; 33(2):682-7. 7. Gallagher S, Phillips AC, Drayson MT, Carroll D. Parental caregivers of children with developmental disabilities mount a poor antibody response to pneumococcal vaccination. Brain Behavior and Immunity. 2009; 23(3):338-46. 8. Bourke-Taylor H, Pallant JF, Law M, Howie L. Predicting mental health among mothers of school-aged children with developmental disabilities: The relative contribution of child, maternal and environmental factors. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2012; 33(6):1732-40. 9. Raina P, O'Donnell M, Rosenbaum P, Brehaut J, Walter SD, Russell D, et al. The Health and Well-Being of Caregivers of Children With Cerebral Palsy. Pediatrics. 2005; 115(6):626-36. 10. Tsai SM, Wang HH. The relationship between caregiver's strain and social support among mothers with intellectually disabled children. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009; 18(4):539-48. 11. Herring S, Gray K, Taffe J, Tonge B, Sweeney D, Einfeld S. Behaviour and emotional problems in toddlers with pervasive developmental disorders and developmental delay: associations with parental mental health and family functioning. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006; 50(12):874-82. 25 12. Murphy NA, Christian B, Caplin DA, Young PC. The health of caregivers for children with disabilities: caregiver perspectives. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2007; 33(2):180-7. 13. Bourke-Taylor H, Howie L, Law M. Impact of caring for a school-aged child with a disability: understanding mothers' perspectives. Aust Occup Ther J. 2010; 57(2):127-36. 14. McLennan JD, Kotelchuck M. Parental Prevention Practices for Young Children in the Context of Maternal Depression. Pediatrics. 2000; 105(5):1090-5. 15. Beresford BA. Resources and strategies: how parents cope with the care of a disabled child. Journal Of Child Psychology And Psychiatry, And Allied Disciplines. 1994; 35(1):171-209. 16. Oelofsen N, Richardson P. Sense of coherence and parenting stress in mothers and fathers of preschool children with developmental disability. Journal Of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 2006; 31(1):1-12. 17. Smith LE, Seltzer MM, Tager-Flusberg H, Greenberg JS, Carter AS. A Comparative Analysis of Well-Being and Coping among Mothers of Toddlers and Mothers of Adolescents with ASD. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2008; 38(5):876-89. 18. Abbeduto L, Seltzer MM, Shattuck P, Krauss MW, Orsmond G, Murphy MM. Psychological well-being and coping in mothers of youths with autism, Down syndrome, or fragile X syndrome. Am J Ment Retard. 2004; 109(3):237-54. 19. Tong HC, Haig AJ, Nelson VS, Yamakawa KS, Kandala G, Shin KY. Low back pain in adult female caregivers of children with physical disabilities. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003; 157(11):1128-33. 20. Brehaut JC, Kohen DE, Raina P, Walter SD, Russell DJ, Swinton M, et al. The Health of Primary Caregivers of Children With Cerebral Palsy: How Does It Compare With That of Other Canadian Caregivers? Pediatrics. 2004; 114(2):182-91. 21. Gallagher S, Phillips AC, Carroll D. Parental stress is associated with poor sleep quality in parents caring for children with developmental disabilities. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010; 35(7):728-37. 22. Butcher PR, Wind T, Bouma A. Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of a child with a hemiparesis: sources of stress, intervening factors and long-term expressions of stress. Child: Care, Health & Development. 2008; 34(4):530-41. 23. Bourke-Taylor H, Pallant JF, Law M, Howie L. Predicting mental health among mothers of school-aged children with developmental disabilities: the relative contribution of child, maternal and environmental factors. Res Dev Disabil. 2012; 33(6):1732-40. 26 24. Khanna R, Madhavan SS, Smith MJ, Patrick JH, Tworek C, Becker-Cottrill B. Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life Among Primary Caregivers of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 2011; 41(9):1214-27. 25. Raina P, O'Donnell M, Rosenbaum P, Brehaut J, Walter SD, Russell D, et al. The health and well-being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2005; 115(6):626-36. 26. Mitchell W, Sloper P. Information that informs rather than alienates families with disabled children: developing a model of good practice. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2002; 10(2):74-81. 27 Appendices Appendix 1: Resource review tables Table 1. Australian resources that include information on mental health and well-being in carers or parents of children with a disability. No. 1 Resource Title Parent to Parent: Raising you child with special needs Organisation Joint production of the Department of Human Services and Deakin University Format Online and booklet form Subsection title Looking after yourself Headings (wellbeing content) Why self-care is important Ideas for looking after yourself Respite care Support groups 10 hot tips for staying cool 2 Kindergarten inclusion tip sheets: Looking after yourself Association for Children with a Disability Online Looking after yourself 3 Learning To Lead: A parent guide to planning supports for your child with a disability and family Association for Children with a Disability Online Building your support network - Through the Maze: An Overview of services and support for parents of children with a disability in Victoria There’s no such thing as a silly guide: A practical guide for families living with a child with chronic illness, disability Association for Children with a Disability 4 5 Identifying the Supports you need InterACT Online and booklet form Counselling and Support Booklet Where do we begin - Time to yourself Filling the time Accepting help Going back to work Counselling Siblings Respite Other support Circles of support Inviting people to join a circle of support Circle of support get-togethers - Informal and formal support Respite Care - Coping strategies - Respite - Key sources of support Family and friends Taking care of yourself Caring for the whole family The non-primary carers perspective Siblings Who will help us in the community How to give life balance - 28 No. 6 Resource Title Children with Disability: Family Life Organisation Raising Children Network Format Online website and pdf Subsection title Your feelings Family relationships – Talking about disability Headings (wellbeing content) - What to expect - Different relationships, different feelings - Tips for coping with your feelings - Why can it be hard to talk to others Who should I talk to and why? Tips for talking about the diagnosis Other wellbeing resources that have contributed to the development of the project resource, but were not specific to parents and carers are shown in the below table. Table 2. Summary of Australian resources that contain information on wellbeing and mental health not specific to parents and carers of children with a disability. Organisation Document Title Australian Government Taking a Break Feelings Taking Care of Yourself Carers Australia Talking it over Carers Victoria Look after yourself Carers Queensland National Carers Counselling Program Kids Matter All About Parent and Carer Mental Health beyondblue The beyondblue Guide for Carers – Supporting and caring for a person with depression, anxiety and/or a related disorder. How to Look After Your Mental Health Mental Health Foundation 29 Appendix 2: Interview Questions for parents and carers Stage 1: Resource development (Researcher to explain the process of the NDIS and the role of LACs. Researcher to also provide a brief overview of the term wellbeing) Questions: 1) What information would you like to see included in a resource that would assist and support your wellbeing? 2) Is there any information that you do not think would be helpful in a resource? 3) What format do you think the new resource needs to be in? A few examples of formats include an on-line downloadable document like a pdf, a website, an application or “app” on a mobile device, or a paper-based leaflet or brochure. 4) Are there any qualities in a resource that would make you more likely to use it? 5) Would you find it useful to receive assistance or support from a LAC when you use the resource, or would you prefer to use it alone? Stage 2: Resource appraisal (Researcher to circulate resource designed for parents/carers prior to interview) Questions: 1) How did you feel after reading this resource? Do you have any comments about how useful this was for you? 2) Are there any changes that you would like us to make to the information included in the resource? 3) Is there any information that you felt was missing in the resource? 30 Appendix 3: Interview Questions for health and disability professionals Stage 1: Resource development (Researcher to explain the process of the NDIS and the role of LACs) Questions: 1) What information do you think is important in a resource that aims to assist and support the wellbeing of parents and carers raising a child with a disability? 2) What do you think needs to be included in a resource intended for LACs to assist and support the wellbeing of parents and carers raising a child with a disability? 3) What format do you think would be most effective for the new LAC resource? Formats can include an on-line internet site, application on a mobile device or leaflet based. Is there another format that you consider helpful? 4) Are you aware of any current resources that LAC’s could use to help or support the wellbeing of parents and carers? If so, can you think of their strengths and weaknesses? 5) In what ways could a LAC provide assistance in terms of going through the resource with parents and carers? 6) Can you think of any specific skills that LACs need to have in order to go through the resource with parents and carers? Stage 2: Resource appraisal (Researcher to circulate new resource designed for LACs prior to interview) Questions: 1) How useful do you think this resource will be useful for parents and LACs? 2) Are there any changes that you would like us to make to the information included in the resource? 3) Is there any information that you felt was missing in the resource? 31