PSYC-674 - Advanced Biological Psychology

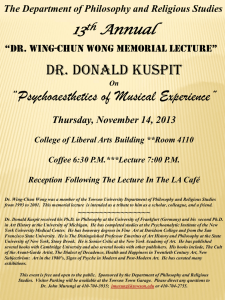

advertisement

ADVANCED BIOLOGICAL PSYCHOLOGY PSYC.674.101 Fall, 2014 INSTRUCTOR: Bryan D. Devan, Ph.D. CLASS MEETING: College of Liberal Arts Bldg, LA 2150, Thur 4:20 PM – 6:50 PM OFFICE AND PHONE: CLA; LA 3146; 410.704.3727 OFFICE HOURS: Mon-Thur: 3:20-4:20PM; OR BY APPOINTMENT EMAIL: bdevan@towson.edu CLASS WEBSITE: http://pages.towson.edu/bdevan/Adv_biopsych.htm MAC FRIENDLY HOMEPAGE: http://pages.towson.edu/bdevan HOMEPAGE: http://pages.towson.edu/bdevan/Welcome.htm (internet explorer) LABORATORY WEBSITE: http://pages.towson.edu/bdevan/LCN.htm (internet explorer) Background Resources Brain Facts A Primer on the Brain and Nervous System http://www.sfn.org/index.aspx?pagename=brainfacts © 2008, Society for Neuroscience Neuroscience: Science of the Brain An Introduction for Young Students www.sfn-montreal.ca/baw/brainbee/Eng.pdf © 2003, British Neuroscience Association Course Objectives Provide a primer of knowledge as the basis for more advanced critical thinking Review some of the major research methods, findings and theories in the field of biological psychology (obviously not an exhaustive account but the psychological interests of the students will be taken into consideration) Understand important brain-behavior relations and some contemporary problems that biopsychologists are attempting to answer Survey and evaluate the literature on a specific topic in the field Design and propose a novel research project OPTION 1: conduct the research study and report on the results OPTION 2: A Take home final exam will replace option 1, in which all material covered in class may be used to develop follow-questions that the students may independently work on for the period between the final class meeting and the scheduled final exam. The exam will require significant research that not only draws upon course content but should include 2 significant work, at the graduate level, that expands on and includes topics not covered in the course. Description As outlined above, the main objectives of this course are twofold: 1) to review specific content in the field of biopsychology and 2) to critically evaluate contemporary research and conduct a novel study in this broad area of investigation. Readings from the journal articles, books, lecture material and multimedia presentations will focus on key questions that neuroscientists ask about the brain and behavior. During the first few weeks, students will do a literature search and select a topic involving the relationship between brain and behavior (or more generally biologypsychological function) to present to the class for consideration in developing group research projects (see below). A five page written summary of the topic (with APA citations and at least – the absolute minimum requirement – 5 references to journal articles) should be submitted by midterm (week 8). Some prospective topics and methods will be presented during the first few weeks, along with a list of research articles that may be helpful in developing ideas for individual topics and the research projects. Each student will give a 10-15 minute presentation on their chosen research topic, followed by group discussion (led by the presenter) of some general ideas for research (including hypotheses, experimental design and methodology). Participation in class discussion is an integral part of planning each research project; therefore, part of your course grade will be based on class participation. For the research component of the course, students may work in groups (2-4 individuals) on a research project (laboratory experiment or field study) that is based on the former class presentations and discussion. Individuals within a group will work together on developing a formal research proposal using resources available in the department. A tour of laboratory facilities will be given at this time as each group considers the available options. Each group will then meet with me to formalize their plans and subsequently present a summary of the proposal to the class for further consideration and fine-tuning. Each group will write up a short proposal/research protocol and fill out the required forms that must be submitted and approved by the Towson University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, vertebrate animals) or Institutional Research Board (IRB, human subjects) prior to beginning the research. Given time constraints on obtaining approval, completing the research and reporting the results, you are encouraged to use noninvasive (or less invasive, i.e., nonsurgical) methods for the course investigation. Research leading to follow-up study using more invasive procedures may be considered if individuals are committed to using such methods in their thesis research or other outside work (this should be discussed with me). At the end of the course each group will submit a manuscript, written in APA journal format. If Option 2 above is chosen individual students will be given a Take home examination covering material presented in class but also requiring significant knowledge that may be gained through follow-up research of peer-reviewed scholarly journals and books. COURSE SCHEDULE (Subject to change as necessary) Week Date 1 Aug 28 2 Sept 4 3 Sept 11 Topics/discussion Localization of brain functions Biopsychology as a neuroscience Neuroanatomy: structure of the brain Sex, stress, and spatial navigation Neurophysiology & Synaptic transmission Psychopharmacology and Dopamine theories of Schizophrenia Assignments Literature review Literature review Literature review 3 4 Sept 18 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Sept 25 Oct 2 Oct 9 Oct 16 Oct 23 Oct 30 Nov 6 Nov 13 Nov 20 Nov 27 15 Dec 4 16 Dec 11 Epi-gentics, nutrition and brain health Endogenous psychopharmacology Psychosurgery and neuroimaging Brainstorming (food for thought) V.S. Ramachandran: neurodetective Brain transplant (MPTP-induced PD) Ghosts in your genes Group proposal presentations Animal minds: intelligence Animal minds: emotions Statistical results and interpretation Thanksgiving Final report presentations Alternative assignment given Final written report due (APA format) Presentations Presentations D-day (design/decision) IACUC/IRB submission Introduction/Method Introduction/Method Group proposal presentations Data collection Data collection Data collection and analysis No Class Final report presentations or Take-home final exam Final class meeting Final exam due GRADES Individual component (120 points) Literature review (topic of your choice but must include brain-behavior content) Presentation (lit review summary and general research proposal) – 40 points Written summary in APA format (5 pages, minimum of 5 references) – 60 points Participation in class discussion – 20 points Option 1 Group component (80 points) Group proposal presentation – 20 points (one grade is earned by all group members) Final report presentation – 20 points (same as above) Final paper in APA format – 40 points (same as above) Option 2(80 points) 10 Essay questions – You choose 8 of the 10 questions to answer, each worth 10 points (at least 5 peer-reviewed scholarly references/question must be included and provided electronically) Total points = 200 Change in Grading System for Graduate Courses Following approvals from the Graduate Studies Committee and the University Senate (at its February meeting), the system of grading graduate courses will change effective with the Fall 2010 Semester. The previous system used was A/B/C/F. The new system is: A = 4.00 / A- = 3.67 / B+ = 3.33 / B = 3.00 / C = 2.00 / F = 0.00 As before, a 3.00 average is required to remain in good academic standing and to graduate. Also, as before, a student’s overall graduate program can include no more than two grades of C. ACADEMIC INTEGRITY EXPECTATIONS: Towson University’s full policy to address the variety of behaviors that represent a breach of academic integrity can be found in Appendix F of the University Catalog. In addition, if you type in “Academic Integrity Policy” in the search box in the upper right-hand corner of the Towson University webpage, you will be taken to a page of links. Click on “Towson University Policies” and open the “Academic Affairs” link. You will find a link to the full Academic Integrity Policy at that location. The site can be access by clicking the following link: 4 https://inside.towson.edu/generalcampus/tupolicies/documents/0301.00%20Student%20Academic%20Integrity%20Policy.pdf PLAGIARISM AND CHEATING: Plagiarism and cheating will not be tolerated. There are several types of plagiarism. The most obvious variety occurs when an individual presents someone else’s ideas as his/her own. This plagiarism can be avoided simply by giving credit to the appropriate source. A second type occurs when credit has been given but the individual uses the same wording or nearly the same wording as the source. This also is plagiarism and can be avoided by substantially recasting the idea in your own words. Looking at someone else’s paper during an exam or giving aid to someone else during an exam will be interpreted as cheating. The first instance of either plagiarism or cheating will result in an automatic zero for the examination or assignment in question. The second instance will result in an automatic failure of the course and possible suspension from the University. ATTENDANCE: Regular attendance is expected and is necessary for good performance. Attendance will be taken on a regular basis and will be considered in the case of a borderline grade. You are responsible for any material or information presented in class, whether you attend or not. I strongly recommend that you make arrangements with others in the class ahead of time to find out what you will miss if you cannot attend class. REPEATING THIS COURSE: University policy states that a student may not repeat a course more than once without specific prior permission from the Academic Standards Committee. If you have taken this course twice before and have not received written permission from the Academic Standards Committee to take the course a third time, you should not be registered in this course - please consult the Registrar's office about the procedure for petitioning the Academic Standards Committee. SPECIAL NEEDS: For any student who may need an accommodation due to a disability, please make an appointment to see me during my office hours. A memo from Disability Support Services authorizing your accommodations will be required. EMERGENCY STATEMENT: In the event of a University-wide emergency, course requirements deadlines and grading schemes are subject to changes that may include alternative delivery methods, alternative methods of interaction with the instructor, class materials, and/or classmates, a revised attendance policy, and a revised semester calendar and/or grading scheme. In the case of a University-wide emergency, please refer to the following about changes in this course: Course web page (see above) Instructor’s email (see above) Emergency telephone number (i.e., my mobile # -- 410/446-1425) For general information about any emergency situation, please refer to the following: 1) Towson University’s Website: www.towson.edu 2) TU Text Alert System: This is a service designed to alert the Towson University community via text messages to cell phones when situations arise on campus that affect the ability of the campus to function normally. Sign up: http://www.towson.edu/adminfinance/facilities/police/campusemergency/ Please note: I will attempt to communicate with you via your Towson e-mail address, the course webpage (given above) and/or the course Blackboard site. GENERAL INFORMATION: Please turn off cell phones and other electronic devices that emit audible sounds during class. This syllabus is subject to change at the discretion of the instructor. Journal Articles (check the class website weekly for the posting of journal articles for discussion) The below references may be of use in developing research projects. In addition, several reference sources will be provided electronically to each student for gaining background and pursuing research topics. 5 Astur, R. S., Ortiz, M. L., & Sutherland, R. J. (1998). A characterization of performance by men and women in a virtual Morris water task: a large and reliable sex difference. Behav Brain Res, 93, 185-190. Astur, R. S., Tropp, J., Sava, S., Constable, R. T., & Markus, E. J. (2004). Sex differences and correlations in a virtual Morris water task, a virtual radial arm maze, and mental rotation. Behav Brain Res, 151, 103-115. Beiko, J., Lander, R., Hampson, E., Boon, F., & Cain, D. P. (2004). Contribution of sex differences in the acute stress response to sex differences in water maze performance in the rat. Behav Brain Res, 151, 239-253. Benedetti, F., Colloca, L., Torre, E., Lanotte, M., Melcarne, A., Pesare, M., Bergamasco, B., & Lopiano, L. (2004). Placebo-responsive Parkinson patients show decreased activity in single neurons of subthalamic nucleus. Nat Neurosci, 7, 587-588. Benedetti, F., Lanotte, M., Lopiano, L., & Colloca, L. (2007). When words are painful: unraveling the mechanisms of the nocebo effect. Neuroscience, 147, 260-271. Benedetti, F., Mayberg, H. S., Wager, T. D., Stohler, C. S., & Zubieta, J. K. (2005). Neurobiological mechanisms of the placebo effect. J Neurosci, 25, 10390-10402. Bizon, J. L., LaSarge, C. L., Montgomery, K. S., McDermott, A. N., Setlow, B., & Griffith, W. H. (2009). Spatial reference and working memory across the lifespan of male Fischer 344 rats. Neurobiol Aging, 30, 646-655. Bliss, T. V. (1999). Young receptors make smart mice. Nature, 401, 25-27. Bruce, D. (2001). Fifty years since Lashley's In search of the Engram: refutations and conjectures. J Hist Neurosci, 10, 308-318. Caldarone, B. J., King, S. L., & Picciotto, M. R. (2008). Sex differences in anxiety-like behavior and locomotor activity following chronic nicotine exposure in mice. Neurosci Lett, 439, 187191. Clinton, L. K., Billings, L. M., Green, K. N., Caccamo, A., Ngo, J., Oddo, S., McGaugh, J. L., & LaFerla, F. M. (2007). Age-dependent sexual dimorphism in cognition and stress response in the 3xTg-AD mice. Neurobiol Dis, 28, 76-82. Corder, R. (2008). Red wine, chocolate and vascular health: developing the evidence base. Heart, 94, 821-823. Crews, W. D., Jr., Harrison, D. W., & Wright, J. W. (2008). A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of the effects of dark chocolate and cocoa on variables associated with neuropsychological functioning and cardiovascular health: clinical findings from a sample of healthy, cognitively intact older adults. Am J Clin Nutr, 87, 872-880. Driscoll, I., Hamilton, D. A., Yeo, R. A., Brooks, W. M., & Sutherland, R. J. (2005). Virtual navigation in humans: the impact of age, sex, and hormones on place learning. Horm Behav, 47, 326-335. Falk, D. (2009). New Information about Albert Einstein's Brain. Front Evol Neurosci, 1, 3. Gallop, G. G., Jr. (1970). Chimpanzees: self-recognition. Science, 167, 86-87. Gomez-Pinilla, F. (2008). Brain foods: the effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat Rev Neurosci, 9, 568-578. Hamilton, D. A., Akers, K. G., Johnson, T. E., Rice, J. P., Candelaria, F. T., & Redhead, E. S. (2009). Evidence for a shift from place navigation to directional responding in one variant of the Morris water task. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process, 35, 271-278. Hamilton, D. A., Akers, K. G., Johnson, T. E., Rice, J. P., Candelaria, F. T., Sutherland, R. J., Weisend, M. P., & Redhead, E. S. (2008). The relative influence of place and direction in the Morris water task. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process, 34, 31-53. Hamilton, D. A., Akers, K. G., Weisend, M. P., & Sutherland, R. J. (2007). How do room and apparatus cues control navigation in the Morris water task? Evidence for distinct contributions to a movement vector. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process, 33, 100-114. Hamilton, D. A., Johnson, T. E., Redhead, E. S., & Verney, S. P. (2009). Control of rodent and human spatial navigation by room and apparatus cues. Behav Processes, 81, 154-169. Healy, S. D., Braham, S. R., & Braithwaite, V. A. (1999). Spatial working memory in rats: no differences between the sexes. Proc Biol Sci, 266, 2303-2308. Hebb, D. O. (1959). Intelligence, brain function and the theory of mind. Brain, 82, 260-275. Hirstein, W., & Ramachandran, V. S. (1997). Capgras syndrome: a novel probe for understanding the neural representation of the identity and familiarity of persons. Proc Biol Sci, 264, 437444. Jonasson, Z. (2005). Meta-analysis of sex differences in rodent models of learning and memory: a review of behavioral and biological data. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 28, 811-825. 6 Lashley, K. S. (1950). In search of the engram, Society of Experimental Biology Symposium No. 4: Physiological mechanisms in animal behaviour (pp. 454-482). Cambridge, England. Levenson, J. M., & Sweatt, J. D. (2005). Epigenetic mechanisms in memory formation. Nat Rev Neurosci, 6, 108-118. Levy, L. J., Astur, R. S., & Frick, K. M. (2005). Men and women differ in object memory but not performance of a virtual radial maze. Behav Neurosci, 119, 853-862. McDonald, R. J., Hong, N. S., Craig, L. A., Holahan, M. R., Louis, M., & Muller, R. U. (2005). NMDA-receptor blockade by CPP impairs post-training consolidation of a rapidly acquired spatial representation in rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci, 22, 1201-1213. McDonald, R. J., & White, N. M. (1993). A triple dissociation of memory systems: hippocampus, amygdala, and dorsal striatum. Behav Neurosci, 107, 3-22. McGaugh, J. L. (1966). Time-dependent processes in memory storage. Science, 153, 1351-1358. Milner, P. M. (1993). The mind and Donald O. Hebb. Sci Am, 268, 124-129. Morris, R. G. M. (1981). Spatial localization does not require the presence of local cues. Learning and Motivation, 12, 239-260. Mueller, S. C., Jackson, C. P., & Skelton, R. W. (2008). Sex differences in a virtual water maze: an eye tracking and pupillometry study. Behav Brain Res, 193, 209-215. Newhouse, P., Newhouse, C., & Astur, R. S. (2007). Sex differences in visual-spatial learning using a virtual water maze in pre-pubertal children. Behav Brain Res, 183, 1-7. Nurk, E., Refsum, H., Drevon, C. A., Tell, G. S., Nygaard, H. A., Engedal, K., & Smith, A. D. (2009). Intake of flavonoid-rich wine, tea, and chocolate by elderly men and women is associated with better cognitive test performance. J Nutr, 139, 120-127. O'Keefe, J., & Nadel, L. (1978). The Hippocampus as a Cognitive Map. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Papini, M. R. (2008). Integrating learning, emotion, behavior theory, development, and neurobiology: the enduring legacy of Abram Amsel (1922-2006). Am J Psychol, 121, 661669. Plotnik, J. M., de Waal, F. B., Moore, D., 3rd, & Reiss, D. (2009). Self-recognition in the Asian elephant and future directions for cognitive research with elephants in zoological settings. Zoo Biol. Plotnik, J. M., de Waal, F. B., & Reiss, D. (2006). Self-recognition in an Asian elephant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 103, 17053-17057. Poldrack, R. A., Clark, J., Pare-Blagoev, E. J., Shohamy, D., Creso Moyano, J., Myers, C., & Gluck, M. A. (2001). Interactive memory systems in the human brain. Nature, 414, 546-550. Poldrack, R. A., & Packard, M. G. (2003). Competition among multiple memory systems: converging evidence from animal and human brain studies. Neuropsychologia, 41, 245-251. Pollo, A., Torre, E., Lopiano, L., Rizzone, M., Lanotte, M., Cavanna, A., Bergamasco, B., & Benedetti, F. (2002). Expectation modulates the response to subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinsonian patients. Neuroreport, 13, 1383-1386. Prior, H., Schwarz, A., & Gunturkun, O. (2008). Mirror-induced behavior in the magpie (Pica pica): evidence of self-recognition. PLoS Biol, 6, e202. Rahman, Q., & Koerting, J. (2008). Sexual orientation-related differences in allocentric spatial memory tasks. Hippocampus, 18, 55-63. Ramachandran, V. S., & Hirstein, W. (1998). The perception of phantom limbs. The D. O. Hebb lecture. Brain, 121 ( Pt 9), 1603-1630. Reul, J. M., & Chandramohan, Y. (2007). Epigenetic mechanisms in stress-related memory formation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 32 Suppl 1, S21-25. Roof, R. L., & Stein, D. G. (1999). Gender differences in Morris water maze performance depend on task parameters. Physiol Behav, 68, 81-86. Suddendorf, T., & Collier-Baker, E. (2009). The evolution of primate visual self-recognition: evidence of absence in lesser apes. Proc Biol Sci, 276, 1671-1677. Swartz, K. B. (1997). What is mirror self-recognition in nonhuman primates, and what is it not? Ann N Y Acad Sci, 818, 64-71. Tang, Y. P., Shimizu, E., Dube, G. R., Rampon, C., Kerchner, G. A., Zhuo, M., Liu, G., & Tsien, J. Z. (1999). Genetic enhancement of learning and memory in mice. Nature, 401, 63-69. Wu, A., Ying, Z., & Gomez-Pinilla, F. (2008). Docosahexaenoic acid dietary supplementation enhances the effects of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition. Neuroscience, 155, 751-759. Yuan, T. F. (2009). Einstein's brain: gliogenesis in autism? Med Hypotheses, 72, 753. Zeman, A. (2006). What do we mean by "conscious" and "aware"? Neuropsychol Rehabil, 16, 356-376.