Causation, Grounding and Abstracta: the Unity of

advertisement

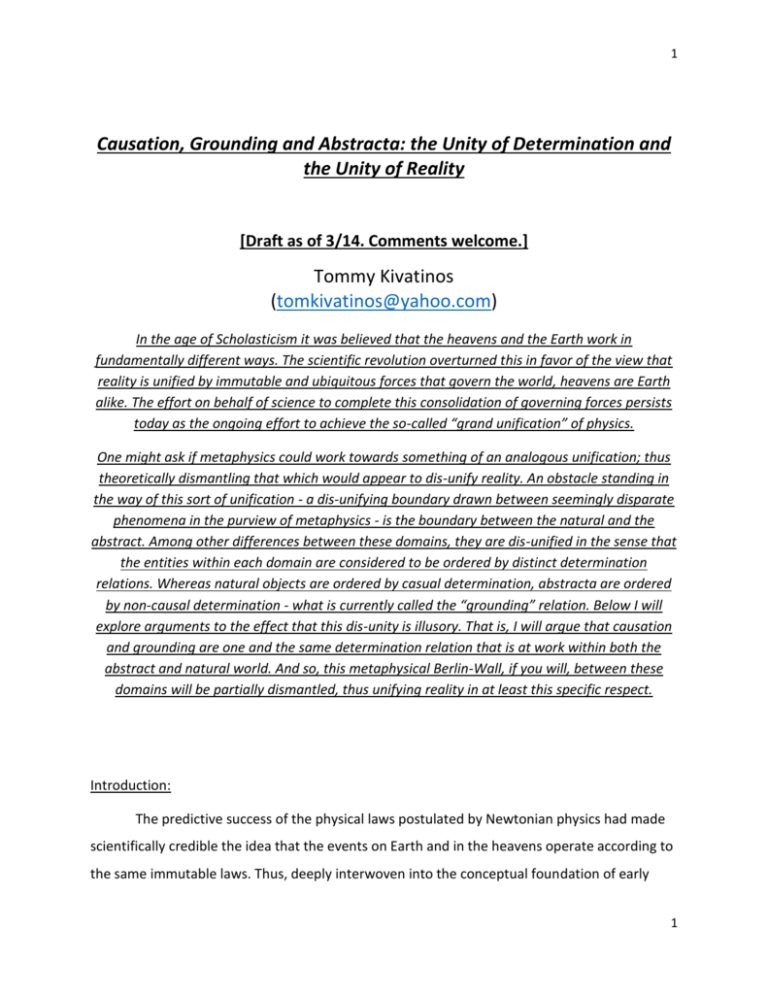

1 Causation, Grounding and Abstracta: the Unity of Determination and the Unity of Reality [Draft as of 3/14. Comments welcome.] Tommy Kivatinos (tomkivatinos@yahoo.com) In the age of Scholasticism it was believed that the heavens and the Earth work in fundamentally different ways. The scientific revolution overturned this in favor of the view that reality is unified by immutable and ubiquitous forces that govern the world, heavens are Earth alike. The effort on behalf of science to complete this consolidation of governing forces persists today as the ongoing effort to achieve the so-called “grand unification” of physics. One might ask if metaphysics could work towards something of an analogous unification; thus theoretically dismantling that which would appear to dis-unify reality. An obstacle standing in the way of this sort of unification - a dis-unifying boundary drawn between seemingly disparate phenomena in the purview of metaphysics - is the boundary between the natural and the abstract. Among other differences between these domains, they are dis-unified in the sense that the entities within each domain are considered to be ordered by distinct determination relations. Whereas natural objects are ordered by casual determination, abstracta are ordered by non-causal determination - what is currently called the “grounding” relation. Below I will explore arguments to the effect that this dis-unity is illusory. That is, I will argue that causation and grounding are one and the same determination relation that is at work within both the abstract and natural world. And so, this metaphysical Berlin-Wall, if you will, between these domains will be partially dismantled, thus unifying reality in at least this specific respect. Introduction: The predictive success of the physical laws postulated by Newtonian physics had made scientifically credible the idea that the events on Earth and in the heavens operate according to the same immutable laws. Thus, deeply interwoven into the conceptual foundation of early 1 2 physics was the basic idea that the entirety of nature is unified by ubiquitous causal mechanisms described by these laws. Though the evolution of physics had pushed Newtonian Theory to the theoretical wayside this basic idea remains in its foundation still to this day. This is perhaps most obviously evidenced in the effort of contemporary physics to achieve a “grand unification”: the formulation of a single framework that captures the complete set of the immutable forces that govern nature, both at the macro level of Relativity and the micro level of Quantum Mechanics.1 One might ask; can metaphysics work towards something of an analogous unification? That is, one might wonder if the variegated phenomena within the purview of metaphysics could be coherently described as governed by the very same apparatuses, roughly speaking. If the attempt was made to take steps towards such a unification, one of the obstacles standing in the way of this would hinge upon the topic of abstracta. This is what my discussion below addresses: an ontological boundary - a sort of metaphysical Berlin-Wall, if you will - is thought to stand between the natural world and the world of the abstract. I will argue that this wall can be partially dismantled. Despite persisting Humean concerns about causation,2 the notion of causal determination remains one that philosophers still commonly appeal to as that which imposes an ontological ordering on natural objects: it’s not an unfamiliar idea that events are caused by other events and thus events and the concreta involved in these events can be made intelligible by virtue of this ontological ordering. Likewise, philosophical discourse often portrays abstracta as bearing determination relations that imposes an ordering upon them: the existence of a set is sometimes thought to be determined by its members;3 a proposition’s truth is sometimes thought to be determined by its truthmaker;4 a number’s identity is sometimes thought to be determined by its location in a mathematical structure;5 a proposition’s meaning is sometimes thought to be determined by the meanings of the words that compose it;6 etc. However, it’s thought that whatever causation amounts to, it cannot take abstracta as its relata. So despite 1 For an overview see Morrison (2013). For an overview see Schaffer (2013). 3 For instance, see Fine (1994). 4 For instance, see any of the papers in Beebee and Dodd (2005). 5 For instance, see Horsten (2012); section 4.2. 6 For instance, Szabó (2013). 2 2 3 the fact that both the abstract and the natural domains contain determination relations, these ordering apparatuses are considered to be somehow fundamentally distinct. The boundary drawn between these determination relations is thus one of the boundaries drawn between the purportedly dis-unified domains of the natural and the abstract. Contrary to this picture, below I criticize arguments to the effect that the determination relation which holds between abstracta and causation are distinct. In turn, I will argue that both the abstract and the natural world are unified in the respect that they are governed by the same, single kind of determination relation. In section 1 I provide an outline of grounding – the determination relation that takes abstracta as its relata in addition to natural phenomena. In section 2 I will criticize the basic argument that grounding and causation ought to be considered distinct in virtue of the fact that grounding can take abstracta as relata whereas causation cannot. In section 3 I address a connected issue: the issue that determination relations between abstracta obtain atemporally whereas determination relations between concreta obtain temporally. I argue that this difference does not justify the distinction between grounding and causation. In section 4 I end by suggesting a positive reason to consider these relations to be one and the same based upon my suggested method of individuating relations. Section 1: Non-Causal Determination - Grounding A notion of determination that is thought to take abstracta as its relata has received tremendous attention recently. This is the notion of grounding; which I will frame my discussion below in terms of. Though some accounts regiment grounding as a sentential operator,7 I will follow Schaffer (2009)’s influential account and thus present grounding as a relation that holds between entities of arbitrary ontological categories. 7 Correia (2009); Fine (2001). 3 4 Grounding can be understood in various ways. It is often presented in terms of its connection to the notion of fundamentality. That is, grounding is often understood as the relation that connects the fundamental and the derivative levels of reality: the fundamental grounds the derivative. For example, the macroscopic is often thought to be derivative of the microscopic which thus grounds the macroscopic.8 Alternatively, grounding is often linked to the notion of metaphysical explanation whereby grounding amounts to some kind of noncausal explanatory connection.9 To illustrate, fact F1 that someone has knowledge that P holds can be explained by appeal to the fact F2 that this person has justified true belief that P holds (assuming a simple JTB account of knowledge for the sake of illustration). Thus F2 serves to metaphysically explain and thus ground F1.10 Most useful for the discussion below; grounding is sometime presented simply as asymmetric non-causal determination.11 To illustrate, grounding is thought to be the sort of relation that is involved in such examples as moral facts being determined by natural facts; mental states being determined by neural states; modality being determined by actuality; dispositional properties being determined by categorical properties; etc.12 Despite the tremendous attention recently placed upon grounding,13 a profound assumption entertained by nearly accounts of the matter has yet to be challenged. This is the assumption that grounding is somehow distinct from causation.14 Indeed, the similarity between the two is striking: both can be understood as asymmetrical and explanatory relations whereby something happening or holding depends upon something else happening or holding. In fact, the comparison between grounding and causation is one of the most common tools that authors in the relevant literature use in order to introduce the concept to their readers. As Schaffer (2012) introduces the concept of grounding at the very outset of discussion 8 deRosset (2013); Von Solodkoff (2011). Audi (2012); Fine (2012). 10 I take this example from Trogdon (2013). 11 See Daly (2012); Fine (2012). 12 For a host of more helpful examples, see Rosen (2010). 13 For an overview, see Clark and Liggins (2012) or Trogdon (Forthcoming; 2013a). 14 Amongst those who explicitly hold the relations to be distinct, are the following: deRosset (2013); Fine (2012); Trogdon (2012); Rosen (2010); Schaffer (2012); Von Solodkoff (2011). 9 4 5 on the topic, he says “[g]rounding is something like metaphysical causation. Roughly speaking, just as causation links the world across time, grounding links the world across levels.” Trogdon (2014) introduces the concept of grounding by contrasting causal explanation with the kind of explanation that grounding corresponds to; thus drawing on the explanatory similarity between the relations. And Audi (2012) describes grounding as a “non-causal relation of determination” thus drawing on the determinative similarity between the relations in order to make clear the basic concept of grounding to his readers. Hence a natural question that this similarity raises is; exactly what is the feature of grounding or causation that they are distinct in virtue of? There are many features that are worthy of assessing as such a candidate feature. Below, I wish to assess one specific feature of grounding in order to argue that it fails to serve as a convincing basis for treating grounding and causation as distinct. This is the feature of grounding such that grounding does or can hold between abstracta whereas causation does not and cannot. Section 2: The Fallacy of the Argument from Abstracta The purported claim that grounding holds between abstracta whereas causation cannot allows for an argument in favor of the distinction between these relations that I will call the “argument from abstracta.” This argument can be formulated as follows: Premise 1: Causation can hold only between natural relata and thus cannot hold between abstract relata.15 Premise 2: Grounding can hold between abstract relata. Conclusion: Causation and grounding are distinct. 15 The widespread endorsement of this claim is illustrated by comments in Swoyer (2008) which offers a delineation of the general and traditional conception of abstracta held by philosophers: “… the philosophically important features of the paradigm examples of [abstracta]… are pretty clear. They are atemporal, non-spatial and acausal – i.e. they do not exist in time or space (or space-time), they cannot make anything happen, nothing can affect them, and they are incapable of change.” P. 13-14. 5 6 In short, the problem with the argument is that it requires a false assumption. The conclusion of the argument follows from premises 1 and 2 only if a particular assumption is true – an assumption I will call the “abstracta segregation assumption” and abbreviate as “AB-S-A.” This assumption runs as follows: AB-S-A: A relation kind cannot have tokens of two sets such that the relation tokens in one set take natural relata and the relations tokens in the other set take abstract relata. The falsity of AB-S-A is easily illustrated by considering counter examples; such as the identity relation. All identity relation tokens belong to the same relation kind despite the fact that some of these tokens take natural relata whereas some take abstract relata. If we accept AB-S-A we would be committed to treating identity relation tokens that take natural relata to belong to a different relation kind than identity relations tokens that take abstract relata. But accepting this seems obviously a mistake: identity relation tokens are all tokens of the same kind - identity - despite the difference in the ontological status of their relata. This falsifies the AB-S-A. Another counter example is supervenience. Some supervenience relations hold between abstracta and some hold between natural relata. If we accept AB-S-A we would be committed to treating supervenience relation tokens that take natural relata to belong to a different relation kind than supervenience relations tokens that take abstract relata. But accepting this seems obviously a mistake: supervenience relation tokens are all tokens of the same kind - supervenience - despite the difference in the ontological status of their relata. Thus AB-S-A is false: it’s false that any single relation kind cannot have some tokens that take physical relata and some tokens that take abstract relata. The argument from abstracta therefore fails. Hence, just as identity (or supervenience) takes relata of different ontological statuses yet is the same relation in all cases, the same could hold for grounding / causation. Section 3: The Fallacy of the Argument from Atemporality 6 7 My discussion thus far has focused on the ontological status of the relata taken by grounding and causation. But underlying the purported fact that grounding holds between abstracta whereas causation does not is yet an entirely different reason to think that the relations are distinct. This is the following reason: what obtains in the abstract domain obtains atemporally whereas what obtains in the natural domain obtains temporally. Thus underlying the issue concerning the difference in the ontological status of relata is this issue concerning a difference in the temporal conditions under which the relations obtain.16 This difference allows for another argument in favor of the distinction between grounding and causation, which I will call the “argument from atemporality.” This argument can be formulated as follows: Premise 1*: Grounding obtains atemporally, given that it obtains between abstract relata.17 Premise 2*: Causation obtains temporally, given that it obtains between natural relata. Conclusion: Grounding and causation are distinct. This argument fails for the same reason that the argument from abstracta fails: the argument requires a false assumption. The conclusion of the argument follows from premises 1* and 2* only if a particular assumption is true. I will call this assumption the “atemporality segregation assumption” and abbreviate it as “AT-S-A.” This assumption runs as follows: AT-S-A: A relation kind cannot have tokens of two sets such that the relation tokens in one set obtain temporally and the relations tokens in the other set obtain atemporally. Mirroring the line of thought in the previous section, the falsity of AT-S-A is easily illustrated by considering counter examples, such as those mentioned above - identity or supervenience. All token identity relations are of the same kind despite the fact that some of these token identity relations obtain temporally - between natural relata - whereas some token 16 This connection between the ontological status of something as abstract and it being atemporal is illustrated by the same quote by Swoyer (2008) presented above in footnote 14. 17 Said more carefully, Premise 1* is: In the cases in which grounding obtains between abstract relata, it obtains atemporally. Stated this way, Premise 1* is sensitive to the fact that grounding obtains temporally in the cases such that it obtains between concreta. 7 8 identity relations obtain atemporally - between abstract relata. This falsifies the AT-S-A, as would running the same line of thought about supervenience or any relation that holds both between both the natural and the abstract. In turn, just as was the case with the issue of the purported difference in the ontological status of the relata of grounding and causation, the purported difference in these conditions under which they obtain fails to justify the distinction between the relations. Section 4: Individuating Relation Kinds [SECTION TO BE ADDED] References Audi, Paul (ed.) (Forthcoming). The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, third edition. (Forthcoming). — (2012). A Clarification and Defense of the Notion of Grounding. In Correia et al. (2012). Batterman, Robert (ed.) (2013). Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Physics. Oxford University Press. New York. Beebee, Helen and Dodd, Julian (ed.s) (2005). Truthmakers: The Contemporary Debate. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Correia, Fabrice and Schnieder, Benjamin (eds.) (2013). Metaphysical Grounding – Understanding the Structure of Reality. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Clark, Michael J. and David Liggins (2012). Recent work on grounding. Analysis 72, no. 4: 812823. Daly, Chris (2012). Skepticism About Grounding. In Correia et al. (2012). deRosset, Louis (2013). Grounding Explanations. Philosophers’ Imprint, 13(7):1-26. Fine, Kit (2012). Guide to Ground. In Correia et al. (2012). — (2001). The Question of Realism. Philosopher’s Imprint 1: 1-30. — (1994). Essence and Modality. Philosophical Perspectives 8: 1–16. 8 9 Hoeltje, Miguel, Benjamin Schnieder, and Alexander Steinberg (ed.s) (2013). Varieties of Dependence. Basic Philosophical Concepts, Philosophia Verlag (2013). Hale, Bob and Hoffman, Aviv (eds.) (2010). Modality: Metaphysics, Logic, and Epistemology. Oxford University Press. Horsten, Leon (2012). Philosophy of Mathematics, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), forthcoming URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2012/entries/philosophy-mathematics/>. Morrison, Margaret (2013). Unification in Physics. In (ed.) Batterman (2013) pp. 381-416. Rosen, Gideon (2010). Metaphysical Dependence: Grounding and Reduction. In Hale et al. (2010). pp. 109-36. Schaffer, Jonathan (2009). On what Grounds What. In Chalmers et al. (2009) pp. 347-383. — (2012). Grounding, Transitivity and Contrastivity. In Correia et al. (2012) — (2013). "The Metaphysics of Causation", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2013/entries/causation-metaphysics/> Sider, Theodore, with John Hawthorne and Dean W. Zimmerman (eds.) (2008). Contemporary Debates in Metaphysics. Malden: Blackwell. Swoyer, Chris (2008). Abstract Entities. In Sider et al. (2008). pp. 11-32. Szabó, Zoltán Gendler (2013).Compositionality. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2013/entries/compositionality/>. Trogdon, Kelly (Forthcoming). Grounding. In (ed.) Audi (Forthcoming). — (2013a). An Introduction to Grounding. In Hoeltje et al (2013) pp. 97-122. — (2013b). Grounding: Necessary or Contingent? Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 94/4: 465-485. Von Solodkoff, Tatjana, (2011). Setting Priority Straight. Philosophical Studies. Volume 161, Issue 3, pp. 391-401. 9 10 10