What is the bindi?

advertisement

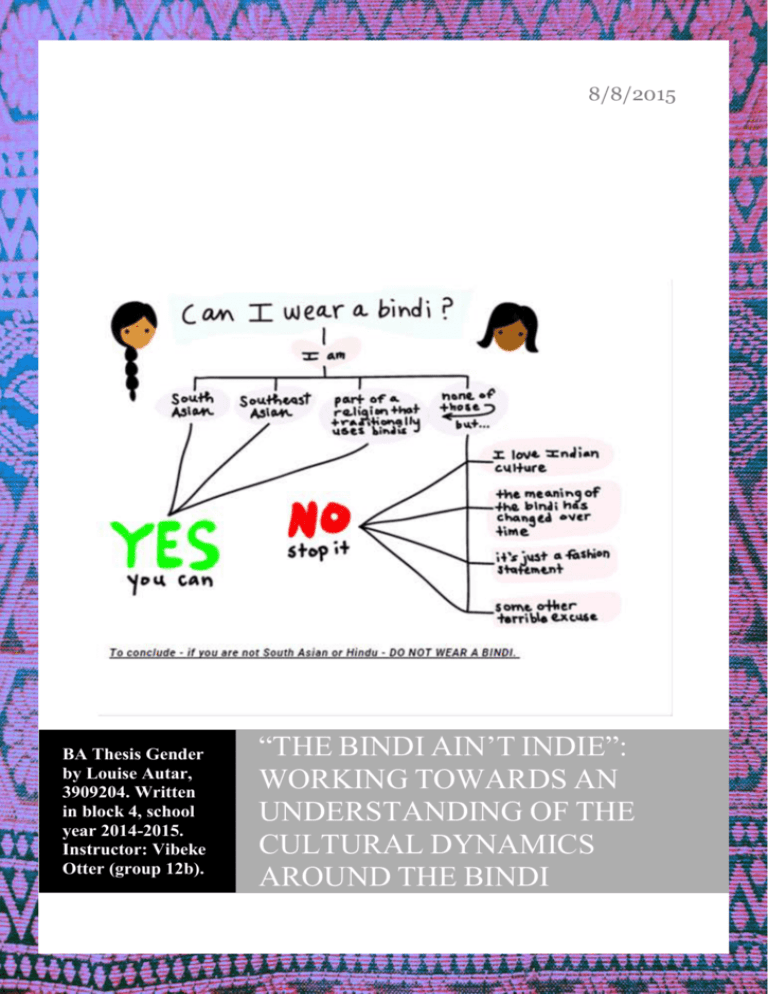

8/8/2015 BA Thesis Gender by Louise Autar, 3909204. Written in block 4, school year 2014-2015. Instructor: Vibeke Otter (group 12b). “THE BINDI AIN’T INDIE”: WORKING TOWARDS AN UNDERSTANDING OF THE CULTURAL DYNAMICS AROUND THE BINDI Abstract Cultural appropriation is emerging as an academic field of research, as well as getting more attention in mainstream media. Many objectors to cultural appropriation have taken onto the internet to express their criticism, with blogging website Tumblr being one of the platforms. In the first half of 2015, Tumblr became home to the Reclaim the Bindi-campaign. The bindi is a South Asian ornamental dot worn between the eyebrows, worn traditionally for socio-cultural and religious reasons. Yet, recently, the bindi has been worn by many white girls, who disregard these traditional reasons in order to improve their look. The Coachella festival in the United States of America was one of such event which saw such appropriation on a wide scale. The RTBcampaign was held in April 2015 as a direct retaliation against the appropriation of cultural items like the bindi, and lasted for the same amount of time as the Coachella festival. During this campaign, primarily girls of desi descent, living in western countries, posted pictures of themselves wearing bindi’s or Indian clothing. These blog-posts often also contained text, in which the participants repeated the general slogans (‘the bindie ain’t indie’, ‘my culture is not an accessory’ or ‘#Coachellashutdown’) of the campaign or shared personal experiences about the bindi. Big debates have since been held on who gets to wear the bindi and who does not. This thesis sets out to gain a better understanding of the cultural dynamics that took place during the campaign. I will do so by analyzing seventeen of the most popular posts with text. In analyzing these personal textual narratives using critical discourse analysis, I will answer the following question: To what extent can we develop a better understanding of the current debates around the bindi, through the concept of cultural appropriation? 2 Content Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 What is the bindi? ...................................................................................................................... 6 The traditional significance of the bindi. ............................................................................ 6 The bindi beyond ‘borders’ (of geography and traditional significance). ........................... 6 What is cultural appropriation? ................................................................................................. 9 Methodology..............................................................................................................................12 Reclaim the Bindi-week .....................................................................................................12 Participants of the RTB-week ............................................................................................13 The selection of posts. ........................................................................................................13 Critical Discourse Analysis ................................................................................................14 How can we better understand how the participants of the RTB-week discuss bindi issues through the concept of cultural appropriation? ........................................................................16 Discrimination ...................................................................................................................16 Cultural dominance ........................................................................................................... 17 Assimilation and internalization. ...................................................................................... 17 Cultural exploitation ......................................................................................................... 18 Abstraction and commodification of cultural means ........................................................19 Cultural appropriation: between cultural dominance and exploitation? ......................... 20 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................21 3 Introduction In 2013 , Selena Gomez gave a seductive performance of her song ‘Come and Get It’ at the MTV Awards while wearing a bindi. Her use of the bindi, a sacred adornment worn on the forehead by South-Asian women, led to quite a controversy (Bull & Smart, 2013). A significant critique came from the Universal Society of Hinduism. Its leader, Rajan Zed, an Indo-American Hindu statesman, stated that the bindi “is not meant to be thrown around for seductive effects or as a fashion accessory aiming at the mercantile greed” (Bull & Smart, 2013). Indian actress and singer Priyanka Chopra, however, saw things differently, exclaiming that the growing popularity of the bindi is great. The adornment, according to her, is not limited to its traditional purposes, but also a popular fashion accessory (Jadav, 2013). Selena Gomez’ application of the bindi is not an isolated event, though. The emergence of the bindi as a mainstream fashion item in the West has been observed by Sunaina Maira since the beginning of the 21st century. Maira mapped and analyzed the emergence of ‘indo-chic’ as a style, declaring that the bindi is becoming a commercialized mainstream fashion accessory in the West (Maira, 2000. P.331). This development has been recognized as cultural appropriation by Maira, amongst others, who therefore criticized this development (Maira, 2000. Pp.331-333). Maira’s critique fits into a growing body of work that criticizes cultural appropriation. Bruce Ziff and Pratima V. Rao define cultural appropriation as “the taking- from a culture that is not one’s own- of intellectual property, cultural expressions or artifacts, history and ways of knowledge” (1997. P.1). The easiest rebuttal to this definition is the paradigm that culture is always ‘fluid’, ‘evolving’ (Scafidi, 2005. P.ix) and a process of renegotiation (Mendoza et al, 2002. P. 319). An interesting development around cultural appropriation is the fierce retaliation by the ethnic groups that practice and inherit the cultures that are appropriated. This especially shows on the internet, where digital communities on, for instance Tumblr.com and Facebook.com attack such practices. In doing so, these objectors seem to raise cultural borders and fences, which make explicit who does and does not belong to a certain community or culture and as such, who does and does get to wear the bindi (Brown, 2003. Pp. 3-6). In the case of the bindi, the criticism has taken on an interesting manifestation with the online protest-campaign ‘Reclaim the Bindi’ (RTB)-week on Tumblr.com. This campaign was a direct reaction to the cultural appropriation that takes place at 4 the annual Coachella festival. Generally, the Coachella festival is a musical festival spread out over two weekends in April. Yet, the festival has also become a ‘must’ for so-called ‘trend-watchers’, who get their inspiration for summer wardrobes from the event (Hutchings, 2015). The Coachella festival is important enough to the fashion world to have influential magazines like Vogue reporting the event. In recent years however, the festival has also gained attention due to the frequent appearances of culturally appropriated objects, such as the Native American headdress, and more recently the bindi (Hutchings, 2015). The RTB-week took place at the same time as the Coachella festival and was a conscious protest against the deemed appropriation of the bindi. As the name implies, the goal is to reclaim the bindi from its commercialized mainstream status as a fashion accessory. During the week of the campaign, (diasporic) South Asian girls posted pictures of themselves with bindi’s on, as well as stories of the personal experiences that motivated them to participate. What becomes clear in these individual, personal stories is that the bindi, for them, becomes a sign of the ‘traditional’ culture, but simultaneously also gains new meanings, which makes the the appropriation of the bindi difficult. This thesis, then, seeks to research how the participants of the RTB-week discuss the dynamics around the bindi. This will be done by focusing on seventeen selected desi diasporic participants of the RTB-week, that occurred in the second and third week of April 2015. The umbrella-category of desi includes those who identify as those with ancestors from India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and their diasporas. The word desi has partly derived from des, meaning the home village or country (Vaidhyanathan, 2000; Ausman, 2012. P.1). Simultaneously, however, it also plays with the word pardesi, which means foreigner or stranger, making the desi both familiar and estranged with the country or countries of its ancestors (Ausman, 2012. P.1). The term desi also transcends the national or religious affiliations, drawing together on a shared culture and history of South Asians, even with other differences like religion (Vaidhyanathan, 2000). By relying on both literary research as well as critical discourse analysis on the posts from the selected participants of the Reclaim-the-Bindi week, I hope to answer the following question: To what extent can we develop a better understanding of the current debates around the bindi, through the concept of cultural appropriation? 5 In order to answer my main question, I will answer three sub-questions. Firstly, what is the bindi? Having answered that, I will form my definition of cultural appropriation for this particular case by reviewing various essays on the topic. Then, I will answer the following question: how can we better understand the way participants of the RTB-week discuss the bindi, through the concept of cultural appropriation? In answering these questions, I will be able to answer my main question sufficiently. In doing so, I aspire to shed more light on the difficult subject that is the cultural appropriation of the bindi, as well as why cultural appropriation itself is so hard to define and understand. What is the bindi? The traditional significance of the bindi. Throughout time, the bindi has taken on many significances and shapes. Traditionally, Mary Grace Anthony states, the bindi is “an ornamental dot (…) worn by Hindu women in the middle of the forehead”, that “has had religious connotations within the Indian cultural context” (Anthony, 2010. P. 347). The bindi is also a cosmetic item that enhances the appearance (Bajaj et al, 1989. P.99).This ‘dot’ can differ in color, shape and material, each playing an important role in its significance. Traditionally, the bindi is made from natural powders and dyes. More recently, storebought ‘sticker’ bindi’s have gained popularity as they come in many forms and colors, making them more fashionable (Gupta & Thappa, 2015). Wajihah Hamid explains that the meaning of the bindi can even differ regionally. In North India, for instance, the bindi is a red dot worn by married women only. In the South, however, women of all ages adorn their foreheads with a bindi. (Hamid, 2015. P. 105). In a religious sense, the bindi is also perceived as a third eye, as Hindus believe the center of the forehead, between the brows, is “the center of the created being, and a tool to balance one’s internal energies through meditation” (Anthony, 2010. P.347). This point between the brows is therefore also known as the ajna chakra (third eye), the sixth chakra according to the Yogic scriptures. The bindi beyond ‘borders’ (of geography and traditional significance). Interestingly, most of the literature on the bindi comes from medical disciplines that study allergies and dermatological issues around the bindi (Pandy & Kumar, 1985; 6 Shenoi & Prabhu, 2013; Gupta & Thappa, 2015) . Literature on the signification, but more importantly the resignification of the bindi is slowly emerging since 2000, with the articles of Sunaina Maira, M.G. Anthony and Wajihah Hamid containing the most relevant knowledge to this thesis. Though Anthony quotes Ashok, who states that the bindi is primarily a fashion item nowadays for both Indians and non-Indians alike (Ashok in Anthony, 2010. P. 347), other academics tend to disagree. Sunaina Maira has written extensively on the construction of culture by American ‘desi’s’ around the turn of the century. In her essay ‘Henna and Hip Hop’, published in 2000, she analyzes the identification process of a group of South Asian youngsters and the rise of ‘indo-chic’ as a fashion style. In her introduction, she states: “At certain moments, as when new style tribes emerge or the visual markers associated with one style subculture are taken on by another, these underlying "social values" come under scrutiny, or are simply absorbed into already existing "geographies of difference.” (Maira, 2000. P. 331). Plainly, Maira explains how the appropriation of a cultural object into another culture can force the ‘original’ culture to reconsider what it is that the object truly means to them. Similarly, the rise of ‘indo-chic’ items pushed South Asians to reconsider the value and significance they gave to the objects that were now becoming a fashion style. In this thesis, I maintain that the bindi is also one of such visual markers that brings about scrutiny over the underlying values and layers of significance once picked up by another style subculture. The interest of western countries in South Asian cultures and religions has long been part of history, with the aforementioned ‘indo-chic’ being one of its recent manifestations (Maira, 2000. P.331). In her essay from 2000, Maira offers a critique on the commodification and appropriation of and by Asian American youth cultures, describing how bindi’s became a fetishized symbol for white Americans, symbolizing new orientalism and mysticism (Maira, 2000. P. 359). More importantly, however, this dynamic reveals the hegemony of white femininity over South Asian femininity in western countries, as white women are regarded as trendy and (Indo-)chique in South Asian clothing and adornments, whereas an South Asian woman performing 7 ‘her’ culture would make her ‘Other’ (Anthony, 2010. P.359). It is this very dynamic that will be illustrated in the analysis. Vinay Bahl discusses the layers of significance of South Asian clothing, arguing that the Indian woman abroad must navigate between the contradictory demands of authenticity, assimilation and self-protection (Bahl, 2005. Pp.85-91, 110). In his essay, Bahl remarks that clothing can symbolize defiance, assimilation, conformism, aesthetic, economic status, agency, and gender, cultural, social and religious politics (pp. 85-87). As such, to wear a bindi is a very conscious decision that instantly informs a person who shares the same language or set of codes. But even if there is no shared knowledge, the bindi informs others, if only of their ‘otherness’. Bahl discusses this when he describes the militant New Jersey group ‘dotbusters’, who terrorized desi Americans in the late 1980s. The group of mostly youngsters indulged in hate crimes when they recognized the targets of their violence by the bindi (pp. 108-109; Gutierrez, 1996. Pp. 30, 37). Whereas Maira focuses on the white American response to the bindi, Bahl focuses on various aspects that influence clothing choices of Indian women in India as well as abroad. M.G. Anthony goes a step further, and analyzes the bindi specifically as a “performative symbol to negotiate acceptance or rebellion among Indian and non-Indian women” (Anthony, 2010. P.352). Anthony concludes that the bindi denotes the intersection of different, occasionally rivaling hegemonies, namely religion, nation-state, tradition and fashion (p. 362). To wear, or not wear, a bindi, she argues, is to consciously conform or reject certain power structures, such as families, religions or patriarchies. The argument of the bindi functioning as an intersection between various hegemonies resounds with Wajihah Hamid, who wrote the latest addition to the limited discourse on the bindi. Hamid’s article investigates how the use of the bindi represents the changes in cultural identity of South Asians abroad, addressing the bindi as a marker of cultural identity and gender. Hamid concludes that cultural identity is not merely changed by a change in location, and that the choice to ‘bindify’ (wear the bindi) oneself can arise from moral and religious values, as well as a resistance to complete assimilation (Hamid, 2015. P. 114-115). It is from this point that this thesis departs its own research, looking at how the selected participants perceive the bindi through analyzing their active objections of its appropriation. 8 What is cultural appropriation? Debates about cultural appropriation and what does and does not count as cultural appropriation have slowly gained popularity and media coverage in recent years. Remarkably, however, the definition still varies for different people, which also makes the topic a difficult one to discuss. A first difficulty in approaching cultural appropriation is the difficulty of using suitable definitions of the components, culture and appropriation. Ziff and Rao illustrate this problem by attempting to properly define ‘culture’ and ‘appropriation’. In both cases, they find that one definition will ‘fit’ one casus, while failing the other. In his book Who Owns Native Culture? (2003), Michael F. Brown takes this issue on too, concluding that one cannot apply “grandiose one-size-fits-all models of heritage protection” (p.9) in cultural appropriation cases. Despite such problems, Ziff and Rao do establish three general conclusions about cultural appropriation: (1) appropriation deals with relationships between people, (2) appropriation can present itself in many forms and occasions, and (3) appropriation occurs very often (Ziff & Rao, 1997. P.3). Another difficulty that must be recognized in approaching cultural appropriation is how the concept, as well as its components, are results of what Rosemary J. Coombe calls “traditional Western understandings” (Coombe, 1993. P.249). Coombe explains that the way in which culture, identity and property are understood in the West, undermine, disentitle and disenfranchise the formerly colonized (Coombe, 1993. P. 249), or in Rogers’ words, the subordinate group (Rogers, 2006. P.477). By maintaining these current definitions that are strongly rooted in Western understandings, histories and discourses (Coombe, 1993. Pp.254-255), one will not be able to fully comprehend the implications and complications that cultural appropriation brings about. There are various definitions of cultural appropriation, which are similar overall, but still have little differences that have big implications. Helene Shugart gives one of the earliest definitions of cultural appropriation, stating that the term “refers to any instance in which means commonly associated with and/or perceived as belonging to another are used to further one’s own ends” (Shugart, 1997. Pp.210211). Shugart’s ‘means’ is quite vague, and thus easily applicable in many senses. Her definition focuses on discourse, relying on a body of knowledge or associations to place the ownership of the appropriated ‘means’ by someone. Furthermore, Shugart also includes the question of who the beneficiaries of appropriation are, implying 9 there is a specific goal to the appropriation, making appropriation a very conscious act. In Borrowed Power (1997), Bruce Ziff and Pratima Rao started their book with the following definition of cultural appropriation as the fundament: “the taking -from a culture that is not one’s own- of intellectual property, cultural expressions or artifacts, history and ways of knowledge” (1997. P.1). Ziff and Rao here specify what could be meant with Shugart’s ‘means’, but also use the word ‘taking’, which gives the concept a bad connotation. The authors acknowledge that this definition is broad, but also emphasize that cultural appropriation cannot be captured within one uniform definition that suits every casus. Richard A. Rogers starts his essay ‘From Cultural Exchange to Transculturation’ (2006) by defining cultural appropriation as “the use of a culture’s symbols, artifacts, genres, rituals, or technologies by members of another culture” (Rogers, 2006. P.474). Cultural appropriation, he argues, is inescapable when different cultures collide in any way possible. Remarkable in Rogers’ definition is his choice for the more neutral ‘use’, instead of Ziff and Rao’s ‘taking’. Yet, I would argue that this starting definition lacks at least an implication of power structures, making this particular definition not fully suitable yet for this thesis. Rogers recognizes four categories of cultural appropriation, namely (1) cultural exchange, (2) cultural dominance, (3) cultural exploitation, and (4) transculturation. These categories are defined by the conditions during which the appropriation occurs, as well as the power balance between the to be described groups. Rogers does not particularly focus on one group, instead distinguishing a dominant and a subordinate group. Cultural exchange, he explains, happens when two equally powered groups exchange any of the objects Rogers mentioned in his starting definition. Cultural dominance occurs when the appropriated means are imposed by a dominant culture onto a subordinated culture. The opposite process, in which elements of a subordinated culture are appropriated by the dominant culture without compensation, is cultural exploitation. Finally, transculturation problematizes the implications of the aforementioned categories (Rogers, 2006. Pp. 478-479). The most relevant categories for this work are cultural dominance and exploitation, since these in particular deal with power structures between the dominant and subordinate group. 10 Cultural dominance is characterized by what Rogers calls the “unidirectional imposition of elements of a dominant culture onto a subordinated (…) culture” (Rogers, 2006. P.479). The subordinate group does not really have a choice in ‘accepting’ the imposition, for the dominant culture has more power in whatever way (political, cultural, economical). Yet, though one cannot really resist explicitly, the subordinate may still find ways to reclaim their agency by negotiating the application of the imposition. An important category of cultural dominance is assimilation, in which the imposed culture are internalized, though without guarantee of acceptance within the dominant culture (Rogers, 2006. P.480). Cultural exploitation, on the other hand, entails the appropriation of “elements of a subordinated culture by a dominant culture in which the subordinated culture is treated as a resource to be ‘mined’ and ‘shipped home’ for consumption” (Rogers, 2006. P.486). A first characteristic to this form of appropriation, then, is the lack of reciprocation of any sort. The appropriated element solely serves the dominant culture for its own ends. The second characteristic is the way in which the power of the dominant culture is reinforced through the appropriation. The usage of the appropriated element does not alter the power imbalance but feeds it by emphasizing the structures on which it is built. In Borrowed Power (1997), Ziff and Rao recognized four issues cultural appropriation can bring about. The first is cultural degradation, which occurs when the exploited group is misrepresented and demeaned. The second is that cultural elements must be preserved, where they are best understood. Failing to do so could have debilitating effects and evoke disrespect. The third is the deprivation of material advantage, involving legal and ownership issues in relation to monetary compensations. The fourth is the failure to recognize sovereign claims. The fact that there is not a direct owner of this a cultural element enables its commodification, since the law cannot prohibit this. Commodification, in Rogers’ words, “abstracts the value of an object (or form or person) so that can enter systems of exchange (Rogers, 2006. P.488). As such, the appropriated commodity transforms into a fetish without intrinsic value (Ziff & Rao, 1997. Pp. 8-11; Rogers, 2006. Pp.486-488). In this thesis I will use cultural appropriation will mostly refer to the conscious exploitation of a subordinate culture’s symbols, artifacts, genres, rituals, or technologies by members of a dominant culture. More specifically, cultural appropriation in this thesis entails the conscious exploitation of the bindi as worn by 11 women of desi backgrounds, residing in Western hegemonic countries, by white women in countries with Western hegemony. As such, I mostly side with Rogers’ types of cultural appropriation, as he focuses on the power dynamics different forms of appropriation bring along, while also using Shugart’s addition of exploitation being a conscious process. Methodology Reclaim the Bindi-week The name Reclaim the Bindi has been coined by Tumblr-user Banglebanger, who runs a fashion blog that seeks to incorporate both Indian and American fashion in her looks (banglebanger.com/about). As aforementioned in the introduction, the RTBweek is primarily concerned with South Asian girls, who feel the need to reclaim the bindi in reaction to its recent usage by white girls on festivals. The RTB-week was held parallel to the Coachella festival in America (Hutchings,2015), which took place in the second and third week of April 2015. During this week, Tumblr-users who identified as ‘desi’ posted selfies wearing bindi’s, in reaction to what they deemed to be the cultural appropriation of the bindi by white girls. The participants of the RTB-week let the religious, cultural and geographical differences momentarily be of less importance than the desi online community that transcends these borders. The RTB-week had many participants, which I cannot all analyze in this relatively short thesis. Therefore, I have made a selection based on popularity in direct relation to the amount of text the participant has written. Some of the most popular posts only contain one or various photos with the slogans, like “the bindi ain’t indie” and “culture isn’t your accessory”. I have chosen to exclude these posts since this thesis does not rely that heavily on the visual aspects of the RTB-week, though this may be suitable for another research. Rather, this thesis will analyze the texts that the chosen participants have written to explain their motivations for participating. By selecting the most popular ones, I hope to analyze the posts that have found the most resonance with others, thus mapping out popular themes important to both the selected users, as well as the desi community on Tumblr. 12 Participants of the RTB-week The necessary information about the chosen participants can be found in a chart in appendix II. In this chart, I have assembled the username, country of residence, age and ‘notes’, derived from either the posts or the personal blogs of the participants. To answer the research question, I will be analyzing seventeen posts by seventeen Tumblr-users. All of selected participants of the RTB-week are female and have South Asian, or desi, roots. From charting the country of residence, the age of the participants and the ‘notes’ from the Tumblr-posts, some general conclusions can be made. Firstly, many of the selected participants are have been born or have moved to a Western country, where there is a western or white hegemony. Of the seventeen participants, the residence of five could not be found. Nine of the selected participants live in the United States of America, two of the selected participants live in the United Kingdom and one of them lives in Australia. More generally for the protest itself, very little participants reside in South Asia. It appears that the need to reclaim the bindi is especially felt by members of desi cultures who reside in western countries. From such a context, it is likely that the need to reclaim is a result of the cultural dynamics of such a country. Another note that can be made is that these participants are nearly all young adults, ranging from 16 to 20 years. This appears to be logical if one looks at the demographics of the website, where the group of 16 to 24 years olds makes up for nearly half of the total amount of users (Smith, 2013). Further academic work would be interesting to look at the relation between this particular generation and cultural appropriation. The selection of posts. In appendix III, I have attached the selected posts of the seventeen participants of the RTB-week. The choice for these seventeen posts is based on the ‘notes’. On Tumblr.com, the blogging-website where this campaign was held, every post has ‘notes’. In the appendix, the notes can be found as the number at the bottom left of every post (appendix II, figures 1-17). A post obtains a note when the post is ‘liked’ or ‘reblogged’. In the case of ‘liking’, the post is appreciated by clicking on a heartsymbol. The ‘reblogging’ is also a sign of appreciation of a post, but goes a step further, as the (re)blogger posts the post on his or her own blog. The consequence of 13 reblogging is that your followers will also see this post on their newsfeed (dashboard), which makes the sharing process considerably easier. The amount of notes in the chart and the posts are as measured on 18 June 2015. As such, looking at the notes of a Tumblr-post gives a proper impression of how many people like or appreciate a post, or how many people agree or find resonance with it (appendix II). It is for this reason why I have chosen to look at the notes per post to measure which ones are the most popular ones. In doing so, I believe to have chosen the posts which many members of the desi community agree with. By analyzing these seventeen posts, conclusions will be made based mostly on these seventeen posts, but in a indirect way also more desi people who agree with what these posts say. Thus, I maintain that the critiques on the cultural appropriation of the bindi is not only felt by those who make posts and participate in the RTBcampaign. Rather, the critiques in the posts find resonance with a much larger part of the desi community on Tumblr. A last point that needs be made about the notes is how one can find the post. All participants have (hash)tagged their post with #reclaimthebindi. By clicking on or searching for this tag, the website assembles every possible post that has been tagged. From thereon, one can sort these findings by ‘most popular’ or ‘most recent’. This is one way by which the post can become visible to other bloggers. Another way by which bloggers can find the posts of participants is by following this participant. For instance, figure 3 shows the participation of Tumblr-user Princefaery, which has 68367 notes. Princefaery’s blog has 6758 followers already, so one could say she is quite popular and hence more likely to get lots of notes. Blogs with less followers are less likely to gain as many notes. A third factor to which the amount of notes can be attributed is timing: a post that is published early on in the RTB-week will likely have more notes that late participations. Critical Discourse Analysis As the name of the online protest indicates, the RTB-week deals with power hierarchies of who can and cannot wear a bindi. To wear the bindi evokes different reactions for different wearers, the desi participants argue: whereas they are discriminated against for performing their cultural identity, white women appropriating these cultures are celebrated. Participating in the RTB-week is thus a conscious rejection of this double standard, which becomes obvious in the texts that 14 accompany their photo’s. It is therefore that I will analyze the power dynamics in these texts using the critical discourse analysis (CDA). This type of analysis is characterized by the qualitative research of a set of, in this case, texts (Midden, 2010. P. 123). I have chosen the CDA because of its emphasis on power structures, as well as its emphasis on the simultaneous existence of multiple signifiers (Anthony, 2010. P. 354). The CDA is particularly invested in the way language and power relate to each other (Wodak & Meyer, 2001. P.2). More specifically, Wodak and Meyer state that the CDA aspires to “investigate critically social inequality as it is expressed, signaled, constituted, legitimized and so on by language use (or in discourse)” (2001. P.2). By taking on a deconstructive approach towards, CDA lends itself well for analyzing the selected posts of the RTB-week, which speak against the described double standard. Wodak and Meyer see language as a tool against power, as well as a tool to change the current power dynamics (Wodak & Meyer, 2001. P.11). Similarly, I will illustrate that the texts of the RTBparticipations go against the double standard, as well as the power dynamics that underlie this double standard. In her essay on the use of the bindi, Mary Grace Anthony analyzes the overarching themes in the posts (Anthony, 2010. P.354). Similarly, I will first categorize the seventeen posts by the topics they talk about. I have distinguished these themes by using CDA to look at the posts. Though the posts are quite personal, many participants use similar concepts or arguments. Therefore, I have chosen to use the following categories: (experienced or feared) discrimination, abstraction or commodification of cultural means, cultural dominance and cultural exploitation. Though these concepts are quite often intertwined, the use of this categorization does help in establishing how the cultural power dynamics around the appropriation of the bindi work. As such, the categories should be understood as layers of a process that is first deconstructed, before I put my findings together to get an overarching comprehension. In order to establish this comprehension, I will first assemble relevant quotes from the participants for each category. Then, I will analyze what the participants say and describe in relation to the theory on cultural appropriation, and to a lesser extent, the bindi. In doing so, the separate ‘categories’ will first be explained, before demonstrating how these categories work when intertwined to establish a more comprehensive understanding. 15 How can we better understand how the participants of the RTB-week discuss bindi issues through the concept of cultural appropriation? Discrimination Many of the participants have accounts of either experienced or feared discrimination. Even if they do not explicitly say that certain profanities have been thrown their way, there does seem to be a similar collection of profanities that are aimed at South Asians. In multiple posts, the participants are discriminated against on the basis of stereotypes. Princefaery describes how she has been called “prudish” and “too traditional”. Another stereotype that is mentioned twice is “terrorist”, based on the common misconceptions about non-Western religions (Kenkvneki, Nirzaa). Physical attributes, or the perceived physical attributes of desi women have also evoked discrimination. Mangomouth names two perceived physical attributes, “dirty” and “stinky”. Nirzaa was bullied for her “sideburns” and “thick eyebrows” and the fact that she was hairier than was normatively accepted in her environment. Kenkvneki has similar experiences, having been bullied about her ‘dirty’ dark skin and “desi features”. She was also subject to jokes about “smelling like curry”, which is both a stereotype and a (racist) perceived physical attribute. In multiple posts, clothing too is described as evoking discrimination. Indianprincesss touches upon this, exclaiming that her bangles, sari’s and bindi’s were once the same reason people wouldn’t speak to her. Deerhearts retells how her traditional clothing caused people to stare at her and give her looks of distaste. This experience reminded her why she avoided doing so in the past, which shows how certain restrictions are internalized. Fear of discrimination plays a big role too in performing one’s cultural identity. Deerhearts also tells about her mother, who has started wearing western clothing because she was afraid of racism. Akihcur too saw this fear of judgment as a reason to not fully appreciate her culture. Vulcan-faerie too states that people made her afraid to express her heritage, also illustrating one of the remarks (“dot-heads”) that reinforced this fear. These experiences of discrimination lay bare what the power structures are in the context of nearly all participants. Assuming all participants live in a western country (see appendix II), their ‘traditional’ desi culture is the subordinate culture, to the dominant white and/or western culture. Thus, the described participants have 16 experienced discrimination because they did not comply to the normative standards of the dominant culture. A divide between the types of discrimination can be made though: whereas physical attributes like skin color, facial features and hair growth can seldom be changed drastically, clothing and the bindi are conscious acts of performing one’s cultural identity. One can choose to not wear a bindi out of fear for discrimination. Thus, to still wear the bindi testifies of a conscious rejection of the imposition of the cultural norms of the dominant group. Cultural dominance Cultural dominance, as explained, occurs when elements of the dominant culture are imposed onto a subordinated culture (Rogers, 2006. P.479). In the posts of these participants, the main imposition is that of the mentalities regarding and perceptions about the desi culture by the Western cultures. The adoption of such notions, ideas and judgments have caused disregard for desi cultures by the participants. To be ‘normal’, in Franceshahaha’s words, in such a scenario, is to assimilate to the dominant culture, in clothing, food, behavior and preferences. Coolghoulz, for instance, describes how she was made fun of at school for wearing Indian clothes and eating Indian food at lunch. Weve-made-it-this-far describes cultural dominance especially well, as she recalls how she assimilated as well as she could, by bleaching her skin, dying her hair, perfecting her English accent and internalizing the perceptions of the dominant culture on desi culture. She describes this process as “assimilation as a survival tactic in a white supremacy”. This survival tactic, Rogers states, can manifest itself it various ways, of which he explains two: assimilation and internalization. Assimilation and internalization. As aforementioned, Rogers explains that assimilation and internalization of elements of the dominant culture are key to the imposition of the dominant culture on the subordinate culture (Rogers, 2006. P. 480). To assimilate in this particular case means that these desi girls adjust to the Western cultures in order to fit in, even though, as Rogers remarks, the assimilation does not guarantee acceptance in the dominant culture (480). The internalization means that the norms and mentalities of the Western culture are ingrained in the minds of the participants. As such, the opinions of the Western culture on desi cultures are internalized by the desi girls. 17 Princefaery describes this in her post as being “shamed for having pride in our culture”. Shame and embarrassment of the desi culture comes up in multiple other posts, like in those of Supernatasha, Mangomouth,Problemathic, Franceshahaha and Coolghoulz. All describe how they felt ashamed of their culture due to the internalized discriminating perceptions of the dominant culture. Franceshahaha describes how she, at age 13, wanted to feel “normal” during celebrations of Tamil culture and considered herself a “real Australian”, while looking down on desi cultures. Later on in her life, however, she becomes more critical of this attitude, as she tells that she learned that “ ’Australian’ was really a codeword for ‘white’”. Franceshahaha also states that she was taught by Australian people to be ashamed of her culture, which is an experience multiple participants share. Exwive, for instance, mentions that she wanted to distance herself from her culture, because that was “what she learned was right from the people who try to wear [our] shit now”. She even drops the word “brainwashed” when she speaks of the internalized hatred she used to have for her culture. Problemathic criticizes imposed assimilation and internalization explicitly, writing that her culture is not defined by the facilitating views of the American society. Interestingly about this statement is that she addresses the power that American society, as the dominant group in her case, has on her cultural experience and identity. In doing so, she very explicitly reclaims the agency that would otherwise be subject to the dominant culture. Similarly, the described experiences show how assimilation politics have a deep impact in the way the participants have constructed their views on their cultures and their cultural identities. The key aspect of assimilation then, in this context, is imposing, which again shows the power dynamic between the Western and the desi groups in such countries. To assimilate in this way, is to accept and internalize the mentalities and notions of the dominant group at the expense of the desi culture. If not ‘properly’ accepted and internalized, the person risks punishment in the form of discrimination. Cultural exploitation Cultural exploitation occurs, as aforementioned, when the elements of a subordinated culture are appropriated by the dominant culture without compensation. Wevemade-it-this-far touches upon this, as she sees white people in the United Kingdom 18 as stealing “the pretty parts”. Rakumari states that “my culture isn’t your accessory”, which touches upon the power imbalance that one culture is degraded to a temporary accessory, that reinforces the power of (members of) the dominant group. Abstraction and commodification of cultural means Another layer of the cultural appropriation, as is discussed, is the abstraction of traditional meaning and the commodification of cultural means by the dominant culture. These processes refer to the forsaking of the religious and socio-cultural significances, instead transforming the object to gain new significances for the dominant culture. One such new significance is that of fashion trends, where the bindi identifies its Western wearer as, in the words of Imalwaysyourgift, “boho”, “chic” and “trendy”. Styles like “boho” play right into the commodification of cultural means, as items like the bindi are appropriated for white people, benefitting white people, as Maira explained earlier. As such, the unequal power relations are reinforced as the subordinate culture does not benefit from the commodification. Problemathic describes this dynamics aptly: “I am jealous of these people can so readily take the beauty of my culture, without having to experience the ugly hatred it once caused me to both receive from others and have for myself”. In other words: members of the dominant culture get to enjoy items of the subordinate culture, without facing the repercussions they would impose on members of the subordinate culture. These repercussions are not only discriminating remarks from others, but also the internalized judgments by one’s self. Franceshahaha too writes about the internalized judgment, as she states: “I’ll be damned if a bunch of white girls at Coachella wear the bindi like a cute play thing, when it’s associated with so much trauma for me and so much of the younger diaspora.” She also addresses another layer of cultural exploitation however, as she juxtaposes the effects of the by her experienced cultural dominance against the effects of the abstraction and commodification that are part of cultural exploitation. Descriptions of this particular simultaneous dynamic reappears in nearly every post, which is why I believe this is the root of the problem: the cultural appropriation that takes place during the simultaneous process of cultural dominance and cultural exploitation. 19 Cultural appropriation: between cultural dominance and exploitation? Many of the participants use the same juxtaposition to explain their motivation to participate in the RTB-week. Princefaery states: “While white people are called ‘chic’ and ‘culturally diverse’ for mocking us with their rhinestone stickers, our culture isn’t a trend, you can’t take it away from us just to achieve your spiritual nirvana”. Coolghoulz, Kenkvneki, Mangomouth, Imalwaysyourgift, Exwive, Deerhearts, Franceshahaha and Indianprincess describe the same simultaneous process in similar styles. All of these emphasize their own experiences of having been mocked, teased, bullied, insulted and discriminated against when they wore bindi’s or any other cultural marker, before juxtaposing them with manifestations of appropriation. Indianprincesss and Kenkvneki, for instance, even observe that those who made fun of them are the very same people who are now appropriating the objects they were once bullied for. Imalwaysyourgift repeats common perceptions and stereotypical questions about desi culture from the past (“It’s funny how your gods are weird”, “why do you worship elephants and cows” and “what’s that thing on your forehead”) and now (“boho”, “chic” and “trendy”) to illustrate the resurgence of ‘Indo-chic’ as a trend. A difference that I observe in these posts regarding this topic, however, is the inclusion and exclusion of desi people in this new ‘Indo-chic’ trend. Indianprincesss proclaims that people now love her for the same cultural objects that earlier were the reason for her exclusion. Thus, she now belongs to the group that is being glorified for such cultural objects. Mangomouth however, rhetorically asks: “ “If we are so dirty and stinky, why are you always wearing our henna, bindi’s and even gods?” Mangomouth thus illustrates the double standard that occurs between cultural exploitation and dominance, where one group is disregarded for what the other group is praised for. More concretely in this case, members of desi culture are still on the edge for performing their culture, while white members of Western societies are getting fully praised. Deerhearts captures the essence this double standard, as she states that “I hate that my mum feels obligated to change her cultural identity to ‘fit in’ to a society, which has begun to claim our identity as their own fashion trend”. These participants thus describe a certain double standard where desi women are ‘punished’ for the same thing white women are glorified for. It is this double standard that the RTB-week, and more generally the objectors to cultural 20 appropriation, are against. The usage of bindi’s by white women can and should be perceived as cultural appropriation, since a cultural object is taken from another culture and reworked as suitable, trendy and above all acceptable on white women, whereas brown/desi women experience radically different repercussions. This process shows the hegemonic power of white femininity over Indian femininity, where the former is still elevated above all others. Thus, in reclaiming the bindi, the participants reclaim more than the bindi: they reclaim the power to (re)construct and renegotiate the aesthetic of desi femininity against white femininity. In even larger context, the RTB-week stands for a conscious rejection of the impositions that assimilation brings about. Though assimilation needs not be a bad thing, in this particular case it plays onto and reinforces a historically constructed power imbalance, where the agency of members of the subordinate culture is limited, while members of the dominant culture have full agency. Conclusion This thesis sought to answer the following question: to what extent can we develop a better understanding of the current debates around the bindi, through the concept of cultural appropriation? Currently, many debates around the bindi are about who gets to wear it. Roughly, one can distinguish those who think anyone can wear it, because culture is dynamic, and those who are determined to build fences around culture. I would argue that neither is completely right or wrong. As I have frequently emphasized, for a desi woman to wear a bindi is a conscious decision to perform her cultural identity. Apart from the traditional religious and socio-cultural significances, the bindi worn by a desi woman in a Western country signifies reclaimed agency against assimilation policies and the internalization of the perceptions of the dominant culture on desi culture. To wear a bindi during the RTB-week then serves to reclaim not only the bindi as part of one’s culture, but also to reclaim the agency to reject the imposing elements of the dominant, Western culture. Interestingly, though the protest was started to reclaim the bindi, many posts barely refer to this ornamental dot. Rather, it functions as a symbol for desi culture in general. The bindi functions as an object to open up the conversation about the hardships that arise when these girls get caught between the simultaneous processes of cultural dominance and cultural exploitation. Though the protest is called Reclaim 21 the Bindi, the bindi thus forms a starting point in a debate about cultural dynamics and appropriation, as well as the power structures that underlie them. As Rogers’ four types of cultural appropriation showed, appropriation is often based on and secured by certain power structures. While cultural exchange is arguably the preferable outcome, Rogers writes this off as an impossible ideal as exchange means having two cultures of equal power due to colonialism. The appropriation of Western cultures, I would argue, is seldom exploitation. Rather, it is a normative imposition on the subordinate group, or, in We-made-it-this-far’s words: “assimilation as a survival technique in a white supremacy”. The processes of dominance and exploitation both occur in the case of the bindi, often simultaneously. Where desi people are supposed to assimilate to Western norms in order to survive, white people do not carry this burden and have enough agency to escape these Western norms. In the case of the bindi, desi girls are discouraged and even discriminated against when wearing the bindi. As in the extreme case of the aforementioned Dotbusters, the bindi marks its desi wearers as representing something different than the dominant culture, and as such a possible threat or a nuisance. Yet, while the bindi on the desi forehead communicates such connotations to the Western audience, the bindi on a white forehead is devoid of such connotations. Instead, the bindi is abstracted of its traditional meanings and racist connotations, mystified and commodified to suit Western interests, for instance, to fitting into Western aesthetic. Moreover, this particular dynamic then shows how appropriation reaffirms the power structures between dominant and subordinate, white/Western and desi, colonizer and colonized. The dominant white culture keeps full agency and power in its rejection of the bindi on a desi forehead and its acceptance of the bindi on a white forehead. Though the appropriated object remains the same, the context changes from person to person. White and desi women thus have different regimes of acceptability: a white woman does not need to assimilate to the norm she sets and thus has greater agency to represent herself as an individual. The RTB-week thus lays bare this fundamental difference in agency, socio-cultural treatment and power between desi and white women. Whereas the first is subjected to the norm the latter sets, the latter has more agency to expand her horizons beyond this norm. Thus, though culture is indeed dynamic, one cannot forsake the colonial history and its longterm impact on the current world. Discrimination, assimilation 22 and internalization of certain values have already shaped this generation as experiencing a power imbalance based on race, ethnicity and culture. To rework this imbalance to a more equal one will take time and will need consideration of the intersectionalities on which both desi and white identities are build. In recognizing this imbalance and work towards a better understanding of such intersectionalities, we can initiate a critical debate on the cultural appropriation of the bindi. This thesis is only a first step in the right direction, however, as many aspects have been left out in order to be as specific as possible. For future academic research to improve our current understanding, one could add theory on white femininity and South Asian femininity. Future academic work on the RTB-week or the participants could take into consideration the generational demographics in relation to cultural appropriation. Additionally, since my selected participants are from Western countries, the opinions of South Asians living in South Asia would be interesting to test the value of lived experiences. Lastly, recently there has been a countermovement called White Girls Do It Better, in which white girls take pride in defying accusations of cultural appropriation. It would be interesting to compare the two movements in their construction of white femininity. 23 Literature Antony, Mary Grace. "On the spot: Seeking acceptance and expressing resistance through the bindi." Journal of International and Intercultural Communication 3.4 (2010): 346-368. Ausman, Tasha. "Indian diasporic films as quantum (third) spaces: A curriculum of cultural translation." (2012). Bahl, Vinay. "Shifting boundaries of “nativity” and “modernity” in south Asian women’s clothes." Dialectical anthropology 29.1 (2005): 85-121. Bajaj, A. K., and A. K. Chatterjee. "Contact depigmentation from free para‐tertiary‐butylphenol in bindi adhesive." Contact dermatitis 22.2 (1990): 99-102. Brown, Michael F. Who Owns Native Culture?. Harvard University Press, 2009. Bull, Sarah, and Heidi Smart. "Not Intended for 'Seductive Effects': Selena Gomez Criticized by Hindu Groups for Wearing Bindi Whilst Performing Sexy Single Come And Get It at MTV Awards." Dailymail.co.uk. Associated Newspapers, 16 Apr. 2013. Web. 18 June 2015. <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-2310247/Selena-Gomez-criticised-Hindugroups-wearing-bindi-whilst-performing-sexy-single-Come-And-Get-It-MTV-Awards.html. Web: 18 June 2015. Coachella.com. 2015. https://www.coachella.com/settimes/ Web. 18 June 2015. Coombe, Rosemary. "The properties of culture and the politics of possessing identity: Native claims in the cultural appropriation controversy." (1993). Gupta, Divya, and Thappa, Devinder Mohan. "Dermatoses due to indian cultural practices." Indian journal of dermatology 60.1 (2015): 3. Hamid, Wajihah. "Bindi-fying the Self Cultural Identity among Diasporic South Asians." South Asia Research 35.1 (2015): 103-118. Hutchings, Lucy. "Coachella Festival 2015." Vogue UK. Vogue UK, 20 Apr. 2015. Web. 18 June 2015. &lt;http://www.vogue.co.uk/spy/celebrity-photos/2015/04/13/coachellafestival-2015&gt;. Web: 18-06-2015. 24 Jadav, Prathamev. 24-03-2013. Priyanka Chopra: wearing a bindi in music videos doesn’t hurt Indian sentiments. Do you agree? Bollywoodlife.com. http://www.bollywoodlife.com/news-gossip/priyanka-chopra-wearing-a-bindi-inmusic-videos-doesnt-hurt-indian-sentiments-do-you-agree/ . Web: 18-06-2015. Maira, Sunaina. "Henna and hip hop: The politics of cultural production and the work of cultural studies." Journal of Asian American Studies 3.3 (2000): 329-369. Mendoza, S. Lily, Rona T. Halualani, and Jolanta A. Drzewiecka. "Moving the discourse on identities in intercultural communication: Structure, culture, and resignifications." Communication Quarterly 50.3-4 (2002): 312-327. Midden, Eva. Feminism in multicultural societies: An analysis of Dutch multicultural and postsecular developments and their implications for feminist debates. Diss. University of Central Lancashire, 2010. Pandy, R. K., and A. S. Kumar. "Contact leukoderma due to ‘Bindi’and footwear." Dermatology 170.5 (1985): 260-262. Rogers, Richard A. "From cultural exchange to transculturation: A review and reconceptualization of cultural appropriation." Communication Theory 16.4 (2006): 474503. Scafidi, Susan. Who Owns Culture?: Appropriation and Authenticity in American Law. Rutgers University Press, 2005. Shenoi, Shrutakirthi Damodar, and Smitha Prabhu. "Role of cultural factors in the biopsychosocial model of psychosomatic skin diseases: an Indian perspective." Clinics in dermatology 31.1 (2013): 62-65. Shugart, Helene A. "Counterhegemonic acts: Appropriation as a feminist rhetorical strategy." Quarterly Journal of Speech 83.2 (1997): 210-229. Rutgers University Press, 1997. Vaidhyanathan, Siva. 23-6-2000. The Complicated Identity of South Asians. http://modelminority.com/joomla/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&i 25 d=161:the-complicated-identity-of-south-asians-&catid=41:identity&Itemid=56. Web: 18-06-2015. Wodak, Ruth, and Michael Meyer. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. London: SAGE, 2001. Print. Ziff, Bruce H., and Pratima V. Rao. Borrowed Power: Essays on Cultural Appropriation. 26 27 Appendix I: Verklaring Intellectueel Eigendom De Universiteit Utrecht definieert plagiaat als volgt: Plagiaat is het overnemen van stukken, gedachten, redeneringen van anderen en deze laten doorgaan voor eigen werk. De volgende zaken worden in elk geval als plagiaat aangemerkt: • het knippen en plakken van tekst van digitale bronnen zoals encyclopedieën of digitale tijdschriften zonder aanhalingstekens en verwijzing; • het knippen en plakken van teksten van het internet zonder aanhalingstekens en verwijzing; • het overnemen van gedrukt materiaal zoals boeken, tijdschriften of encyclopedieën zonder aanhalingstekens of verwijzing; • het opnemen van een vertaling van teksten van anderen zonder aanhalingstekens en verwijzing (zogenaamd “vertaalplagiaat”); • het parafraseren van teksten van anderen zonder verwijzing. Een parafrase mag nooit bestaan uit louter vervangen van enkele woorden door synoniemen; • het overnemen van beeld-, geluids- of testmateriaal van anderen zonder verwijzing en zodoende laten doorgaan voor eigen werk; • het overnemen van werk van andere studenten en dit laten doorgaan voor eigen werk. Indien dit gebeurt met toestemming van de andere student is de laatste medeplichtig aan plagiaat; • het indienen van werkstukken die verworven zijn van een commerciële instelling (zoals een internetsite met uittreksels of papers) of die al dan niet tegen betaling door iemand anders zijn geschreven. Ik heb bovenstaande definitie van plagiaat zorgvuldig gelezen en verklaar hierbij dat ik mij in het aangehechte BA-eindwerkstuk niet schuldig gemaakt heb aan plagiaat. Tevens verklaar ik dat dit werkstuk niet ingeleverd is/zal worden voor een andere cursus, in de huidige of in aangepaste vorm. Naam: Louise Autar Studentnummer: 3909204 Plaats: Utrecht, Nederland Datum: 8-8-2015 Handtekening: 28 Appendix II: chart of selected participants Users Country of residence 1 Princefaery X 2 Atauntinggesture X 3 Kenkvneki United States of America 4 Supernatasha United States of America 5 Rakumari United States of America 6 Indianprincesss X 7 Nirzaa X 8 Exwive United States of America 9 Akihcur United States of America 10 We-made-it-this- UK far 11 Mangomouth United States of America 12 Deerhearts United States of America 13 Imalwaysyourgif United t Kingdom 14 Vulcanfaerie X 15 Problemathic United States of America 16 Franceshahaha Australia 17 Coolghoulz United States of America Age 16 19 19 Notes (based on likes and reblogs) 68 367 53 674 62 812 17 50 740 18 18 152 X X 18 10 843 7268 3101 17 4255 X 2984 17 2927 20 2764 17 2729 18 16 2704 2672 23 X 2512 2103 X= unknown 29 Appendix III: the 17 posts. Figure 1 Princefaery. 30 Figure 2 Atauntinggesture. 31 Figure 3 Kenkvneki. 32 Figure 4 Supernatasha 33 Figure 5 Rakumari. 34 Figure 6 Indianprincesss. 35 Figure 7 Nirzaa. 36 37 Figure 8 Exwive. 38 Figure 9 Akihcur. 39 Figure 10 Weve-made-it-this-far. 40 41 Figure 11 Mangomouth. 42 Figure 12 Deerhearts. 43 44 Figure 13 Iamalwaysyourgift. 45 Figure 14 Vulcan-faerie. 46 Figure 15 Problemathic. 47 Figure 16 Franceshahaha. 48 49 50 Figure 17 Coolghoulz. 51 52