"THE OTHER AMERICA. (Cover Story)." Newsweek 146.12 (2005)

advertisement

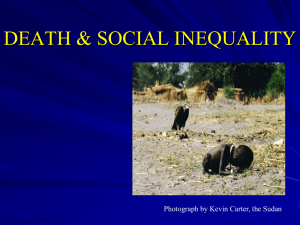

EBSCO Publishing Citation Format: MLA (Modern Language Assoc.): Works Cited Alter, Jonathan, Joseph Contreras, Sarah Childress, Jessica Silver-Greenberg, Anne Underwood, and Pat Wingert. "THE OTHER AMERICA. (Cover Story)." Newsweek 146.12 (2005): 42. MAS Ultra - School Edition. Web. 9 Apr. 2013. Parenthetical for this document: (Alter, et al. 42). Section: Special Report THE OTHER AMERICA AN ENDURING SHAME: Katrina reminded us, but the problem is not new. Why a rising tide of people live in poverty, who they are--and what we can do about it. It takes a hurricane. It takes a catastrophe like Katrina to strip away the old evasions, hypocrisies and not-so-benign neglect. It takes the sight of the United States with a big black eye--visible around the world--to help the rest of us begin to see again. For the moment, at least, Americans are ready to fix their restless gaze on enduring problems of poverty, race and class that have escaped their attention. Does this mean a new war on poverty? No, especially with Katrina's gargantuan price tag. But this disaster may offer a chance to start a skirmish, or at least make Washington think harder about why part of the richest country on earth looks like the Third World. "I hope we realize that the people of New Orleans weren't just abandoned during the hurricane," Sen. Barack Obama said last week on the floor of the Senate. "They were abandoned long ago--to murder and mayhem in the streets, to substandard schools, to dilapidated housing, to inadequate health care, to a pervasive sense of hopelessness." The question now is whether the floodwaters can create a sea change in public perceptions. "Americans tend to think of poor people as being responsible for their own economic woes," says sociologist Andrew Cherlin of Johns Hopkins University. "But this was a case where the poor were clearly not at fault. It was a reminder that we have a moral obligation to provide every American with a decent life." In the last four decades, part of that obligation has been met. Social Security and Medicare have all but eliminated poverty among the elderly. Food stamps have made severe hunger in the United States mostly a thing of the past. A little-known program with bipartisan support and a boring name--the Earned Income Tax Credit--supplements the puny wages of the working poor, helping to lift millions into the lower middle class. But after a decade of improvement in the 1990s, poverty in America is actually getting worse. A rising tide of economic growth is no longer lifting all boats. For the first time in half a century, the third year of a recovery (2004) also saw an increase in poverty. In a nation of nearly 300 million people, the number living below the poverty line ($14,680 for a family of three) recently hit 37 million, up more than a million in a year. With the strain Katrina is placing on the gulf region (and on families putting up their displaced relatives), it will almost certainly increase more. The poverty rate, 12.7 percent, is a controversial measurement, in part because it doesn't include some supplemental programs. But it's the highest in the developed world and more than twice as high as in most other industrialized countries, which all strike a more generous social contract with their weakest citizens. Even if the real number is lower than 37 million, that's a nation of poor people the size of Canada or Morocco living inside the United States. Their fellow Americans know little about them. In the last decade, poverty disappeared from public view. TV dislikes poor people, not personally but because their appearance is a downer and--according to ratings meters--causes viewers to hit the remote. Powerful politicians aren't much friendlier: poor folks vote in small numbers. Republicans win little of their support and Democrats often take it for granted. Until Katrina, the pressure was off. After President Clinton signed welfare reform in 1996, the chattering classes stopped arguing about it. With welfare caseloads cut in half--more than 9 million women and children have left the rolls--even many liberals figured the trend lines were headed in the right direction. The real-world challenges of welfare reform explained in Jason DeParle's landmark 2004 book, "American Dream," went unheeded, as Clinton initiatives and the boom of the 1990s pulled 4.1 million of the working poor out of poverty. (Good times don't always have that effect. The Reagan boom of the 1980s did the same for only 50,000.) Meanwhile crime plummeted in cities across the country, down to levels not seen since the 1950s. Few noticed that progress in fighting poverty stalled with the economy in 2001. President Bush, preoccupied with terrorism and tax cuts, made no mention of it. His main involvement with poverty issues has been on education, where he sharply increased aid to poor schools as part of his No Child Left Behind initiative. Democrats have offered little on education beyond opposition to NCLB. They've shown more allegiance to the teachers unions (whose contracts are models of unaccountability) than to poor kids. Bush's other antipoverty idea was to bolster so-called faith-based initiatives by shifting a little federal funding of social programs to religious groups. Post-Katrina, this will likely be extended. But it's a Band-Aid, not an antipoverty strategy. The last notable poverty expert working in the White House, John Dilulio, departed in 2001 after explaining that the administration had no interest in real policy analysis. The president has made a point of hiring more high-ranking African-Americans than any of his predecessors. But his identification with blacks is a long way from, say, LBJ's intoning, as he did in 1965, "Their cause must be our cause, too… And we shall overcome." Bush rarely meets with the poor or their representatives. His mother made headlines when she visited the Houston Astrodome and said: "So many of the people in the arenas here, you know, were underprivileged anyway. So this is working very well for them"--as if sharing space with 10,000 strangers was a step up. Who are the poor? With whites making up 72 percent of the population, the United States contains more poor whites than poor blacks or Hispanics. In fact, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reports that the increase in white poverty in nonurban areas accounts for most of the recent uptick in the poverty rate. But only a little more than 8 percent of American whites are poor, compared with 22 percent of Hispanics and nearly a quarter of all AfricanAmericans (in a country that is 12 percent black). This represents a significant advance for blacks in recent decades, thanks to the growth of the black middle class, but it's still a shamefully high number. By contrast, immigration has sent poverty among Hispanics up, though it has not been as intractable for them across generations. After 40 years of study, the causes of poverty are still being debated. Liberals say the problem is an economic system that's tilted to the rich; conservatives blame a debilitating culture of poverty. Clearly, it's both--a tangle of financial and personal pain that often goes beyond insufficient resources and lack of training. Family issues are critical. Married-couple families are significantly less poor than female-headed households. While hunger, crime, drugs and overt racial discrimination have eased, other problems connected with poverty may have worsened: wage stagnation, social isolation and a more subtle form of class-based racism. Each can be found in New Orleans, pre-Katrina. The primary economic problem is not unemployment but low wages for workers of all races. With unions weakened and a minimum-wage increase not on the GOP agenda, wages have not kept pace with the cost of living, except at the top. (In 1965, CEOs made 24 times as much as the average worker; by 2003, they earned 185 times as much.) Since 2001, the United States has lost 2.7 million manufacturing jobs. New Orleans's good jobs left much earlier, replaced by employment in the restaurant and tourism industry, which pays less and usually carries no health benefits. Medicaid covers poor children but few poor adults, who put off seeing the doctor, cranking up the cost. For the poor, the idea of low-wage jobs' covering the basic expenses of living has become a cruel joke. Consider the case of Delores Ellis. Before Katrina turned her world upside down, the 51-year-old resident of New Orleans's Ninth Ward was earning the highest salary of her life as a school janitor--$6.50 an hour, no health insurance or pension. Pregnant at 17 and forced to drop out of high school, she went on welfare for a time, then bounced around minimum-wage jobs. "I worked hard all my life and I can't afford nothing," Ellis says. "I'm not saying that I want to keep up with the Joneses, I just want to live better." Ellis is hampered by cultural habits, too. Like almost all poor evacuees interviewed by NEWSWEEK, she has no bank account. Before the storm, she did own a stereo, refrigerator, washer and dryer, two color TVs and a 1992 Chevy Lumina with more than 100,000 miles on it. This, too, is common among the poor; like more comfortable Americans, they spend on consumer goods beyond their means. But these are often their only assets. The reason that more African-Americans didn't heed warnings to leave New Orleans before the hurricane hit goes beyond the muchpublicized lack of cars. They were reluctant to abandon their entire net worth to looters. John Edwards, who has spent much of the year since he lost the vice presidency studying the problems of "the two Americas," says that establishing thousands of bank accounts is critical--not just for Katrina evacuees, but for others in poverty. Isolation is the second big factor that makes poverty even worse. While racial segregation in housing is at its lowest levels since 1920, Sheryll Cashin, author of "The Failures of Integration," has found that only 5 to 10 percent of American families live in stable, integrated communities. More than half a century after Brown v. Board of Education, public schools are still almost totally segregated--the result of where people choose to live, not law. Blacks and whites increasingly go to school with more integrated Hispanics, but not with each other. One big change is that blacks seem only a little more interested in integration than whites. But there's a steep price to this voluntary segregation. While overt discrimination is dwindling--in part because perpetrators can be successfully sued for practicing it--it still exists. A 1999 University of Pennsylvania study showed that telephone callers using "black English" were offered fewer real-estate choices. At a deeper level, Harvard's Glenn C. Loury has identified what he calls "discrimination in contact." Informal contacts between people across racial lines break down wariness and lead to the connections that help people find jobs. When perfectly legal social segregation prevents blacks from having such informal networks, they slip back. This isolation has hampered many Katrina evacuees and other inner-city blacks. Joycelyn Harris has spent her whole life in the Ninth Ward. One of 11 children, she dropped out of school at the age of 12 and went on to have five children of her own, later working at Burger King and as a hotel chambermaid. She and her boyfriend, Kenneth Anthony, fled the city last week with nothing but $9 in their pockets and the clothes on their backs. They lived for a time in a New Orleans housing project isolated by two industrial canals and railroad tracks. "Sometimes I wanted to back out, but you can't," says Anthony, who has lived in four different housing projects. "I felt like I was incarcerated." In the last decade, the government has torn down more than 70,000 units of public housing nationwide, including where Harris and Anthony once lived. But too often, the people who resided there are left to fend for themselves. While everyone agrees that housing vouchers are a good idea, the waiting list to use them for public housing is five years. Following the Gatreaux model in Chicago, the Clinton administration launched a "scatter-site" housing program in four cities that found homes for the poor in mixed-income neighborhoods. While the move doesn't much benefit adults, their children--confronted with higher expectations and a less harmful peer group--do much better. "It really helped in Atlanta," says Rep. John Lewis, a hero of the civil-rights movement. Bush and the GOP Congress killed the idea, as well as the Youth Opportunity Grant program, which had shown success in partnering with the private sector to help prepare disadvantaged teens for work and life. They tried to cut after-school programs--proven winners--by 40 percent, then settled for a freeze. The third problem exacerbating poverty is what some call racism. Others argue the word is too inflammatory for a more subtle but no less debilitating effect. Racism was clearly present in the aftermath of Katrina. Readers of Yahoo News noticed it when a pair of waterlogged whites were described in a caption as "carrying" food while another picture (from a different wire service) of blacks holding food described them as "looters." White suburban police closed at least one bridge to keep a group of blacks from fleeing to white areas. Over the course of two days, a white river-taxi operator from hard-hit St. Bernard Parish rescued scores of people from flooded areas and ferried them to safety. All were white. "A n--ger is a n--ger is a n-ger," he told a NEWSWEEK reporter. Then he said it again. Was the slowness of Washington's rescue efforts also a racial thing? In 2004, Bush moved huge resources into Florida immediately following hurricanes there. No one was stranded. The salient difference was not race but politics. Those hurricanes came just before an election. Obama, the only African-American in the U.S. Senate, says "the ineptitude was colorblind." But he argues that while-contrary to rapper Kanye West's attack on Bush--there was no "active malice," the federal response to Katrina represented "a continuation of passive indifference" on the part of the government. It reflected an unthinking assumption that every American "has the capacity to load up their family in an SUV, fill it up with $100 worth of gasoline, stick some bottled water in the trunk and use a credit card to check into a hotel on safe ground." When they did focus on race in the aftermath, many Louisianans let their fears take over. Lines at gun stores in Baton Rouge, La., snaked out the door. Obama stops short of calling this a sign of racism. For some, he says, it's a product of "sober concern" after the violence in the city; for others, it's closer to "racial stereotyping." Harvard's Loury argued in a 2002 book, "The Anatomy of Racial Inequality," that it's this stereotyping and "racial stigma," more than overt racism, that helps hold blacks in poverty. Loury explains a destructive cycle of "selfreinforcing stereotypes" at school and work. A white employer, for instance, may make a judgment based on prior experience that the young black men he hires are likely to be absent or late for work. So he supervises them more closely. Resenting the scrutiny, the African-Americans figure that they're being disrespected for no good reason, so they might as well act out, which in turn reinforces their boss's stereotype. Everybody goes away angry. Such problems are often less about race than class, which has become a huge factor within the black community, too. It's hard for studious young African-Americans to brave the taunts that they're "acting white." The only answer to that is a redoubled effort within the black community to respect academic achievement and a commitment by white institutions to use affirmative action not just for middle-class minorities but for the poor it was originally designed to help. Beyond the thousands of individual efforts necessary to save New Orleans and ease poverty lie some big political choices. Until Katrina intervened, the top priority for the GOP when Congress reconvened was permanent repeal of the estate tax, which applies to far less than 1 percent of taxpayers. (IRS figures show that only 1,607 wealthy people in Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi even pay the tax, out of more than 4 million taxpayers--one twenty-fifth of 1 percent.) Repeal would cost the government $24 billion a year. Meanwhile, House GOP leaders are set to slash food stamps by billions in order to protect subsidies to wealthy farmers. But Katrina could change the climate. The aftermath was not a good omen for the Grover Norquists of the world, who want to slash taxes more and shrink government to the size where it can be "strangled in the bathtub." What kind of president does George W. Bush want to be? He can limit his legacy to Iraq, the war on terror and tax cuts for the rich--or, if he seizes the moment, he could undertake a midcourse correction that might materially change the lives of millions. Katrina gives Bush an only-Nixon-could-go-to-China opportunity, if he wants it. Margaret Schuber, who evacuated to Atlanta, was a middle-school principal in Jefferson Parish before retiring recently. "I have lived in the city all my life and I didn't realize there were so many people suffering socioeconomically. If you believe in the idea of community, then we all bear responsibility." Schuber is concerned that so many energetic young people aren't planning to return. She's going back to volunteer in the schools. "We all need to do what we can to turn things around," she says. America was built and saved by the Margaret Schubers of the world. Now we need them again, not just in the midst of an emergency but for the hard work of redemption. PHOTO (BLACK & WHITE): LEFT BEHIND: An elderly woman awaits evacuation. TV dislikes images of the poor, but they were omnipresent during the coverage of Katrina. PHOTO (BLACK & WHITE): ONE DAY AT A TIME: >Joe Peters at his tire shop. In the Ninth Ward, good-paying jobs with health benefits are hard to come by. PHOTO (BLACK & WHITE): LIVING FOR THE CITY: Patrick Wicks at his home in New Orleans's Ninth Ward, one of the poorest and most storm-ravaged parts of town PHOTO (BLACK & WHITE): HANGING ON: Joanne Guidos, proprietor of the Cajun Pub, kept her bar open after Katrina, doing a surprisingly brisk business ~~~~~~~~ By Jonathan Alter With Joseph Contreras; Sarah Childress, in New Orleans; Jessica Silver-Greenberg; Anne Underwood, in New York and Pat Wingert, in Washington Copyright of Newsweek is the property of Harman Newsweek LLC and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.