Running Head: PERSON-ORGANIZATION FIT

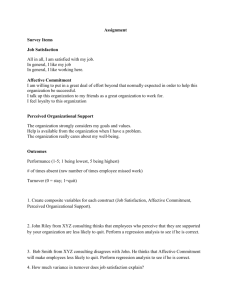

advertisement