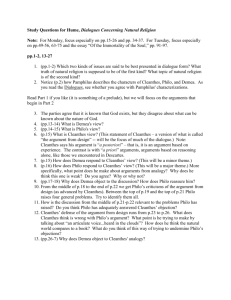

Contemporary Literary and Cultural Theory EN3000 – Fall/Winter

Contemporary Literary and Cultural Theory

EN3000 – Fall/Winter 2011/2012 – Nemanja Protic

Lecture 5 – Oct 6

Last Week

- David Hume’s philosophical scepticism: o Takes empiricism to its logical conclusions, and o Ends in a challenge to western metaphysics.

-

Immanuel Kant’s critique: o Tries to respond to the challenge of Hume’s scepticism by developing a critical philosophy which tries to find the limits of human reason, and o Tries to revive the metaphysical tradition.

Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion:

- Structure: o A conversation between three men overheard and reported by Pamphilus, a student of Cleanthes:

Philo (sceptic)

Cleanthes (a metaphysicist with an anthropomorphic conception of

God).

Demea (mystic) o Even though Philo is a sceptic, he shares with Demea a belief in inscrutability of God.

Extreme vs. Moderate scepticism (tradition and common sense).

- Method: o Cleanthes presents an a posteriori argument for existence of God

(Argument from Design) and Philo critiques it (Part 1 and 2) o Demea presents an a priori argument for existence of God, and Cleanthes and Philo critique it (Part 9) o Throughout the text, Hume employs deductive reasoning as well as inductive reasoning in order to multiply potential explanations for the origin of the universe.

This leads to a suspension of judgement.

Hume’s Conclusions

- There is no world – only individual objects which compose it.

- There is no self – only individual perceptions which compose it.

- There is no necessary relation between ideas which reflect the objective reality

– all our ideas stem from perception and are, consequently, always only related contingently. o The cause-and-effect relation is one of belief and custom: it is itself caused by our experience of observation of cause-and-effect events in the world. o Consequently, there is no metaphysics – all our ideas are strictly based on empirical data and are always related contingently. A priori ideas necessarily connected are always a product of experience and rest on our

faith that nature is regular: this faith, however, may or may not be warranted.

Deductive vs. Inductive Reasoning

- Deductive reasoning – proceeds from a set of premises to a conclusion in order to reach necessary truth. A syllogism is an example of deductive reasoning.

- Inductive reasoning

– proceeds from observable, experienced, individual instances to a general conclusion to reach a probable or contingent truth. o A baseball is round, o A soccer ball is round, o A volleyball is round, o A tennis ball is round, o A golf ball is round therefore

All balls are round.

Demea’s A Priori Argument

“The argument, replied Demea, which I would insist on, is the common one.

Whatever exists must have a cause or reason of its existence; it being absolutely impossible for anything to produce itself, or be the cause of its own existence. In mounting up, therefore, from effects to causes, we must either go on in tracing an infinite succession, without any ultimate cause at all; or must at last have recourse to some ultimate cause, that is necessarily existent: now, that the first supposition is absurd, may be thus proved. In the infinite chain or succession of causes and effects, each single effect is determined to exist by the power and efficacy of that cause which immediately preceded; but the whole eternal chair or succession, taken together, is not determined or caused by anything; and yet it is evident that it requires a cause or reason, as much as any particular object which begins to exi st in time…

The question is still reasonable, why this particular succession of causes existed from eternity, and not any other succession, or no succession at all. If there be no necessarily existent being, any supposition which can be formed is equally possible; nor is there any more absurdity in Nothing’s having existed from eternity, than there is in that succession of causes which constitutes the universe. What was it, then, which determined Something to exist rather than Nothing, and bestowed being on a particular possibility, exclusive of the rest? External causes, there are supposed to be none.

Chance is a word without a meaning. Was it nothing? But that can never produce anything. We must, therefore, have recourse to a necessarily existent being, who carries the reason of his existence in himself, and who cannot be supposed not to exist, without an express contradiction. There is, consequently, such a being; that is, there is a Deity.”

Criticism #1 (Cleanthes)

“I shall begin with observing, that there is an evident absurdity in pretending to demonstrate a matter of fact, or to prove it by any arguments a priori. Nothing is demonstrable, unless the contrary implies a contradiction. Nothing, that is distinctly conceivable, implies a contradiction. Whatever we conceive as existent, we can also conceive as non-existent. There is no being, therefore, whose non-existence implies a

contradiction. Consequently there is no being, whose existence is demonstrable. I propose this argument as entirely decisive, and am willing to rest the whole controversy upon it.

It is pretended that the Deity is a necessarily existent being; and this necessity of his existence is attempted to be explained by asserting, that if we knew his whole essence or nature, we should perceive it to be as impossible for him not to exist, as for twice two not to be four. But it is evident that this can never happen, while our faculties remain the same as at present. It will still be possible for us, at any time, to conceive the non-existence of what we formerly conceived to exist; nor can the mind ever lie under a necessity of supposing any object to remain always in being; in the same manner as we lie under a necessity of always conceiving twice two to be four. The words, therefore, necessary existence, have no meaning; or, which is the same thing, none that is consistent.”

Criticism #2 (Cleanthes)

In such a chain, too, or succession of objects, each part is caused by that which preceded it, and causes that which succeeds it. Where then is the difficulty? But the whole, you say, wants a cause. I answer, that the uniting of these parts into a whole, like the uniting of several distinct countries into one kingdom, or several distinct members into one body, is performed merely by an arbitrary act of the mind, and has no influence on the nature of things. Did I show you the particular causes of each individual in a collection of twenty particles of matter, I should think it very unreasonable, and should you afterwards ask me, what the cause of the whole twenty was. This is sufficiently explained in explaining the cause of the parts.”

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

- Born in Konigsberg, Prussia on April 22, 1724.

-

Claimed that it was David Hume who woke him from his ‘dogmatic slumber’.

- Taught at the University of Konigsberg.

- He lived a solitary life, often shunning the company of others. Once, when a former pupil tried to bring him out of his isolation, he wrote: ‘Any change makes me apprehensive, even if it offers the greatest promise of improving my condition, and I am persuaded by this natural instinct of mine that I must take heed if I wish that the threads which the Fates spin so thin and weak in my case to be spun to any length. My great tanks, to my well-wishers and friends, who think so kindly of me as to undertake my welfare, but at the same time a most humble request to protect me in my current condition from any disturbance.’ o He was sympathetic to the cause of the French Revolution. o Died in Konigsberg, on February 12, 1804.

Kant’s Theory of Knowledge

- All our knowledge begins with experience and it can be either: o Analytic (e.g. ‘all bodies are extended’ or ‘all bachelors are unmarried men’).

Subject and predicate

– this doesn’t add anything to the idea of the body because the body is already extended.

o Synthetic (e.g. ‘all bodies are heavy’ and ‘all bachelors seem happy’).

The predicate adds something new to the subject.

The idea of heaviness, it adds something to the idea of the body, even though we get it from experience.

A priori arguments are always synthetic.

Always lined up by deductive reasoning.

- Judgements based on experience (a posteriori judgements) are always synthetic.

- However, it does not come from it – these are ideas that our ‘faculty of knowledge provides out of itself, which sensible impressions merely prompting it to do this.’

- There are analytic a priori judgements, but is it possible to have synthetic a priori judgements?

Kant’s ‘Copemican Revolution’ (Frederic Copleston, ‘A History of Philosophy’ Vol. VI)

‘What [Kant] is suggesting is that we cannot know things, that they cannot be objects of knowledge for us, except in so far as they are subjected to certain a priori conditions of knowledge on the part of the subject. If we assume that the human mind is purely passive in knowledge, we cannot explain the a priori knowledge which we undoubtedly possess. Let us assume, therefore, that the mind is active. This activity does not mean creation of beings out of nothing. It means rather that the mind imposes, as it were, on the ultimate material of experience its own forms of cognition, determined by the structure of human sensibility and understanding, and that things cannot be known except through the medium of these forms.’

- Kant doesn’t disassociate external objects from our minds – the way we experience these objects is by a priori – he claims we do not have direct access to external reality.

- The realm of phenomena is the realm in which we live.

Phenomena and Noumena

-

Kant called the determination of noumena and pehnomena the ‘noblest enterprise of antiquity,’ but in the Critique of Pure Reason he denied that noumena as objects of pure reason are objects of knowledge, since reason gives knowledge only of objects of sensible intuition (phenomena).

- Noumena ‘in the negative sense’ are objects of which we have no sensible intuition and hence no knowledge at all; these are things-in-themselves.

-

Noumena ‘in the positive sense’ (e.g. the soul and God) are conceived of as objects of intellectual intuition, a mode of knowledge which man does not possess.

- For both Plato and Kant, nevertheless, conceptions of noumena and the intelligible world are foundational for ethical theory. o Phenomenology is the study of how we experience things. o Hegel tries to move beyond this division of Phenomena and Noumena.

The basic movement is that we start with phenomenal knowledge

(with Kant) and the phenomenal knowledge – all reality becomes a theory of how we know things – all reality is knowledge.

Movement from phenomenal into this idea that all reality is a theory of knowledge – a theory of a way in which we understand the world. o However – if we were to make the claim that all this knowledge was all in one person’s head – if all reality were transferred to one person – we end up in solipsism.

Kant’s 4 th Antinomy

- Thesis

– ‘There belongs to the world, either as its part or as its cause, a being that is absolutely necessary.’ o Demea’s a priori proof of God’s existence.

- Antithesis

– ‘An absolutely necessary being nowhere exists in the world, nor does it exist outside the world as its cause.’ o Cleanthes’s counter-argument. o Kant accuses Hume of doing this.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831)

- Born on August 27, 1770 in Stuttgart – German.

- Lived an academic life, teaching at a number of universities in various German states, including Prussia (Germany was unified in 1871).

- Followed the events of the French Revolution with support and enthusiasm.

-

‘Though it is true that Hegel became a philosopher rather than a theologian, his philosophy was always theology in the sense that its subject-matter was, as he himself insisted, the same as the subject-matter of theology, namely the Absolute or, in religious language, God and the relation of the finite to the infinite.’

- This vision of history is directly related to the way in which he views the function of the universe.

- Died in Berlin on November 14, 1831.

Three Ways of Writing History

- He takes particular historical events – things that happen in the world – this content is contingent

– the particular historical and physical things that he looks at are contingent – he uses deductive and inductive reasoning to figure out how the world develops.

- Original history (3

– 5) o Simple reporting/presentation of events and people that take part in these events, without reflecting on what these events are about. o Emerges out of myths, folk songs, and traditions. The difference between original history and myth is that with history ‘a people has reached firm individuality’ (3-4).

The difference between history and myth is that with history the people has reached a firm individuality.

People reaches a firm individuality and starts to reflect on its own history.

- Reflective history (5-10):

A people starts to think about its history. o Universal (6-7)

o Pragmatic (7-9) o Critical (9) o Fragmentary (9-10)

History of philosophy or history of art.

- Philosophical history (10) – embodies all the previous stages, but it expands the methods of history from empirical (a posteriori) to contemplative (a priori) – here we see the union of the particular and the universal in history more concretely. o The highest development of history. o ‘Reason in History’ is an example of philosophical history for Hegel. o All the stages of history continue to exist in philosophical history – all the previous stages live within it.

- Dialectical progression of history. o It moves in three steps: we have a thesis and its antithesis and then we use these contradictions to go above it

– the problem becomes the solution. o Dialectic method is a synthesis of these two worlds for Hegel.

- Hegel starts with phenomena not with ‘I think, I am’ – he starts with objects – with our lives as social being and physical being. o When he starts to investigate how phenomena functions – o He starts with phenomena and his investigation of phenomena leads him to a presupposition

– there was pure thought; ideas with a capital ‘I’ – think of the natural world and then think the opposite of it – just thought without any material reality. o Start with potentiality but end up with actuality

– the process is circular.

Reason in History – Hegel

- Page 11 o What is real is rational and what is rational is real. o We start with pure thought which gets to know itself with human thought. o This process can be investigated using rational categories. o The process is a rational process

– it’s thought getting to know itself through thought.

- Page 20 o The notion of the idea and the notion of the dialectic.

- Page 63 o Art, religion and philosophy which are human activities which bring us closer to the absolute truth.

Art is an emotional understanding

– religion is between art and philosophy – philosophy is the highest way in which we try to understand this process.

Express the same truth but do so differently.

Symbolic art:

Nature is felt to be mysterious and incomprehensible

– this is expressed through symbols.

Classical art:

The pure example of art – central content and ideal form are perfectly joined.

Where the Greeks began to understand that the natural world has both substance and subject.

Romantic art:

A lower form of classical art because it begins to gravitate towards religion.

It is impure.

Concerned more with life of the spirit than the material.

i.e. Christian art.

This is where our conceptual understanding with the world moves from an artistic one to a religious one.