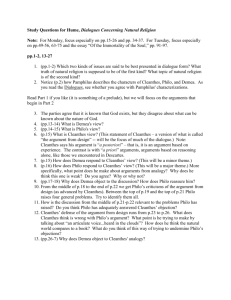

Contemporary Literary and Cultural Theory EN3000 – Fall/Winter

advertisement

Contemporary Literary and Cultural Theory EN3000 – Fall/Winter 2011/2012 – Nemanja Protic Lecture 4 – Sept 29 Continuity between the Modern Era and What came before it “If for a long time the views of… [Modern] philosophers were accepted at their face value, this was partly due to a conviction that in the Middle Ages there was really nothing which merited the name of philosophy. [It was believed that] the flame of independent and creative philosophical reflection which had burned so brightly in ancient Greece was practically extinguished until it… rose in splendour in the 17 th century…” Continuity (Frederic Copleston, ‘A History of Philosophy’ (Volume IV) “But when… more attention came to be paid to mediaeval philosophy, it was seen that this view was exaggerated. And some writers emphasized the continuity between mediaeval and post-mediaeval [i.e. modern] thought. That phenomena of continuity can be observed in the political and social spheres is obvious enough. The patterns of society and of political organization in the seventeenth century clearly did not spring into being without any historical antecedents. We can observe, for instance, the gradual formation of the various national States, the emergence of the great monarchies and the growth of the middle class. Even in the field of science the discontinuity is not quite as great as was once supposed. Recent research has shown the existence of a limited interest in empirical science within the mediaeval period itself… Similarly, certain continuity can be observed within the philosophical sphere. We can see philosophy in the middle Ages gradually winning recognition as a separate branch of study. And we can see lines of thought emerging which anticipate later philosophical developments… Scholars have shown that thinkers such as… Descartes and Locke were subject to the influence of the past to a greater degree than they themselves realized.” Modern Thought – Changes in Emphasis - Traditional learning (exegesis/interpretation of ancient texts) vs. A creation of a new systematic method which did not rely solely on authority of ancient texts. o Rationalism (Descartes) o Empiricism (Locke) - Latin vs. Vernacular (democratization of thought) - Philosophical theologists vs. Theological philosophers - Theological humanism vs. natural humanism - Nature as theocentric vs. nature as mechanistic Science (Frederic Coplestone, ‘A History of Philosophy’, Volume IV) “Science ‘effectively stimulated the mechanistic conception of the world. And this conception was obviously a factor which contributed powerfully to the centering of attention on Nature in the field of philosophy. For Galileo, God is creator and conserver of the world; the great scientist was far from being either an atheist or an agnostic. But nature itself can be considered as a dynamic system for bodies in motion, the intelligible structure of which can be expressed mathematically. And even though we do not know the inner natures of the forces which govern the system and which are revealed in motion susceptible of mathematical statement, we can study Nature without any immediate reference to God. We do not find here a break with mediaeval thought in the sense that God’s existence and activity are either denied or doubted. But we certainly find an important change of interest and emphasis. Whereas the thirteenth-century theologian-philosopher such as St. Bonaventure was interested principally in the material world considered as a shadow or remote revelation of its divine original, the Renaissance scientists, while not denying that Nature has a divine original, is interested primarily in the quantitatively determine immanent structure of the world and its dynamic process. In other words, we have a contrast between the outlook of a theologicallyminded metaphysician who lays emphasis on final causality and the outlook of a theologically-minded metaphysician who lays emphasis on final causality and the outlook of a scientist for whom efficient causality, revealed in mathematicallydeterminable motion, takes the place of final causality.” Descartes’ Mathematical Method - The mathematical method provides answers which cannot be doubted. - Mathematical solutions are eternal. - The mathematical method cannot be challenged – all must assent to its validity. Aristotelian Logic (Syllogism) - Aristotle defines syllogism as ‘a discourse in which, certain things having been supposed, something different from the things supposed results of necessity because these things are so’. (Prior Analytics). - The syllogism is at the roof of deductive reasoning, the goal of which is to show that a conclusion necessarily follows from a set of premises. - For example: o Premise 1 – All men are mortal. o Premise 2 – Socrates is a man. ----------------------------------------------------o Conclusion – Socrates is mortal. Descartes’s Method - Mathematical first principles agree with what we perceive through our sense, metaphysical (philosophical) first principles do not. - “The primary notions that are the presuppositions of geometrical proofs harmonize with the use of our sense, and are readily granted by all… On the contrary, nothing in metaphysics causes more trouble than the making the perceptions of its primary notions clear and distinct. For, though in their own nature they are as intelligible as, or even more intelligible than those that geometricians study, yet being contradicted by the many preconceptions of our sense to which we have since our earliest years been accustomed, they cannot be perfectly apprehended except by those who give strenuous attention and study to them, and withdraw their minds as far as possible from matters corporeal.” Modal Logic (Modalities) - “The modality of a statement or proposition S is the manner in which S’s truth holds. Statements or propositions can be necessary, possible or contingent. For example, while the statement ‘Aristotle is Plato’s student’ is actually true, it is only contingently true. It is possible that Aristotle never met Plato. By contrast, the statement ‘Aristotle is self-identical’ is necessarily true. Aristotle could not have failed to be self-identical… The central issue in the epistemology of modality concerns how we come to have justified beliefs or knowledge of modality.” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) - Modality of necessity o 1+1=2 or o I think, I am - Modality of contingency o My shirt is blue Analysis (Descartes) “Analytic demonstrations are designed to guide the mind, so that all prejudices preventing us from grasping a first principle will be removed, and the first principles themselves can be intuited. An analytic demonstration, therefore, is… a process of ‘reasoning up’ to first principles – the upward movement taking place as prejudice is removed.” John Locke (1632-1704) - Born in Wrington, Somerset, near Bristol on August 29, 1632. - Attended Christ Church, Oxford, but he found works of modern philosophers such as Descartes more interesting than the classical material taught at the university. - Studied medicine, worked as a physician. - His work is equally important, if not more so, in the realm of social and political thought as in the realm of philosophy. ‘His writings influenced Voltaire and Rousseau, many Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, as well as the American revolutionaries. His contributions to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the American Declaration of Independence.’ - Like Descates, he spent time in Holland, escaping political persecution. - Died on October 28, 1704 in England. Empiricism (The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy) “The permanent strand in philosophy that attempts to tie knowledge to experience. Experience is thought of either as the sensory contents of consciousness, or as whatever is expressed in some designated class of statements that can be observed to be true by the use of the senses. Empiricism denies that there is any knowledge outside this class, or at least outside whatever is given by legitimate theorizing on the basis of this class. It may take the form of denying that there is any a priori knowledge, or knowledge of necessary truths, or any innate or intuitive knowledge or general principles gaining credibility simple through the use of reason; it is thus principally contrasted with rationalism. Locke on Rationalism “It is an established opinion amongst some men, that there are in the understanding certain innate principles; some primary notions [and]… characters, as it were stamped upon the mind of man; which the soul receives in its very first being, and brings into the world with it. It would be sufficient to convince unprejudiced readers of the falseness of this supposition, if I should only show (as I hope I shall in the following parts of this Discourse) how men, barely by the use of their natural faculties, may attain to all the knowledge they have, without the help of any innate impressions; and may arrive at certainty, without any such original notions or principles.” Ockham’s razor (A Dictionary of Psychology) “The principle of economy of explanation according to which entities (usually interpreted as assumptions) should not be multiplies beyond necessity (entia non sunt multiplicanda praetor necessitate), and hence simple explanations should be preferred to more complex ones. Another version of the principle attributed to Ockham is that ‘what can be explained by the assumption of fewer things is vainly explained by the assumption of more things.” Deductive vs. Inductive Reasoning - Deductive reasoning – proceeds from a set of premises to a conclusion in order to reach necessary truth. A syllogism is an example of deductive reasoning. - Inductive reasoning – proceeds from observable, experienced, individual instances to a general conclusion to reach a probable or contingent truth. o A basketball is round, o A soccer ball is round, o A volleyball is round, o A tennis ball is round, o A golf ball is round Therefore All balls are round. A Priori “A term applied to statements to reflect that status of our knowledge of their truth (for falsehood). It means literally ‘from what comes before’, where the answer to ‘before what?’ is understood to be ‘experience’. Loosely, one may speak of knowing some truth ‘a priori’ where it is possible to infer the truth without having to experience the state of affairs in virtue of which it is true, but in strict philosophical usage, an a priori must be knowable independently of all experience. Kant held that the criteria of a priori knowledge were (i) necessity, for ‘experience teaches us that a thing is so and so, but not that it cannot be otherwise’, and (ii) universality, for all experience can confer on a judgement is ‘assumed and comparative universality through induction.’” – Oxford Companion to the Mind Locke on Simple Ideas “The senses at first let in particular ideas, and furnish the yet empty cabinet and the mind by degrees growing familiar with some of them, they are lodged in the memory, and names got to them. Afterwards, the mind proceeding further, abstracts them, and by degrees learns the use of general names. In this manner, the mind comes to be furnished with ideas and language, the materials about which to exercise its discursive faculty. And the use of reason becomes daily more visible, as these materials that give it employment increases.” [Book I, Chapter I] Body and Spirit By the complex idea of extended, figured, coloured and all other sensible qualities, which is all that we know of it, we are as far from the idea of the substance of body, as if we knew nothing at all: nor after all the acquaintance and familiarity which we imagine we have with matter, and the many qualities men assure themselves they perceive and know in bodies, will it perhaps upon examination be found, that they have any more or clearer primary ideas belonging to body, than they have belonging to immaterial spirit. The primary ideas we have peculiar to body, as contradistinguished to spirit, are the cohesion of solid, and consequently separable, parts and a power of communication motion by impulse. These, I think, are the original ideas proper and peculiar to body; for figure is but the consequence of finite extension. The ideas we have belonging to peculiar to spirit, are thinking, and will or a power of putting body into motion by thought, and which is consequent to it, liberty. For, as body cannot but communicate its motion by impulse to another body, which it meets with at rest, so the mind can put bodies into motion, or forbear to do so, as it pleases. The ideas of existence, duration, and mobility, are common to them both. Rene Descartes (1596-1650) vs. John Locke (1632-1704) - Rationalism vs. empiricism - Innate ideas vs. ideas acquired through experience; a priori and a posteriori knowledge. - Modality of necessity vs. modality of contingency. - Analysis, deductive reasoning and principle of non-contradiction vs. Empirical observation/experience and inductive reasoning. Today… - David Hume’s philosophical scepticism: o Takes empiricism to its logical conclusions, and o Ends in a challenge to western metaphysics. - Immanuel Kant’s critique: o Tries to respond to the challenge of Hume’s scepticism by developing a critical philosophy which tries to find the limits of human reason, and o Tries to revive the metaphysical tradition. Empiricism “The permanent strand in philosophy that attempts to tie knowledge to experience. Experience is thought of either as the sensory contents of consciousness, or as whatever is expressed in some designated class of statements that can be observed to be true by the use of the senses. Empiricism denies that there is any knowledge outside this class, or at least outside whatever is given by legitimate theorizing on the basis of this class. It may take the form of denying that there is any a priori knowledge, or knowledge of necessary truths, or any innate or intuitive knowledge or general principles gaining credibility simply through the use of reason; it is thus principally contrasted with rationalism.” – Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy Metaphysics Originally a title for those books of Aristotle that came after the Physics, the term is now applied to any enquiry that raises questions about reality that lie beyond or behind those capable of being tackled by the methods of science. Naturally, an immediately contested issue is whether there are any such questions, or whether any text of metaphysics should, in Hume’s words, be ‘committed to the flames, for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.’… The traditional examples will include questions of mind and body, substance and accident, events, causations, and the categories of things that exist… The permanent complaint about metaphysics is that in so far as there are real questions in these areas, ordinary scientific method forms the only possible approach to them… Metaphysics, then, tends to become concerned more with the presuppositions of scientific thought, or of thought in general, although here, too, any suggestion that there is one timeless way in which thought has to be conducted meets sharp opposition. – Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy Scepticism “Although Greek scepticism centred on the value of enquiry questioning, scepticism is now the denial that knowledge or even rational belief is possible… Classically, scepticism springs from the observation that the best methods in some area seem to fall short of giving us contact with the truth (e.g. there is a gulf between appearance and reality), and it frequently cites the conflicting judgements that our methods deliver, with the result that questions of truth become undecidable… As it has come down to us… its method was typically to cite reasons for finding an issue undecidable… Sceptical tendencies emerged in the 14th century… [This medieval scepticism was critical] of any certainty beyond the immediate deliverance of the senses and basic logic… [and it] anticipates the later scepticism of Bayle and Hume. The latter distinguishes between Pyrrhonistic or excessive scepticism, which he regarded as unlivable, and the more mitigated scepticism which accepts every day or commonsense beliefs (albeit not as the delivery of reason, but as due more to custom and habit), but is duly wary of the power of reason to give us much more… Although the phrase ‘Cartesian scepticism’ is sometimes used, Descartes himself was not a sceptic, but in the method of doubt uses a sceptical scenario in order to begin that process of finding a secure mark of knowledge. Descartes himself trusts a category of ‘clear and distinct’ ideas…” - Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy David Hume (1711-1776) - Born in Edinburgh, Scotland on May 7, 1711. - - - Applied for the chair of ethics and pneumatic philosophy at the University of Edinburgh, but was rejected in large part because of his reputation for scepticism and atheism. According to his request, his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion were published posthumously, in 1779. His essays on suicide and immortality appeared anonymously in 1777 and under his name in 1783. In his autobiography, he describes himself as ‘a man of mild disposition, of command of temper, of an open, social, and cheerful humour, capable of attachment, but little susceptible of enmity, and of great moderation in all my passions. Even my love for literary fame, my ruling passion, never soured my temper, notwithstanding my frequent disappointments.’ Died in Edinburgh on August 25, 1776. Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion - Structure: o A conversation between three men overheard and reported by Pamphilus, a student of Cleanthes: Philo (sceptic), Cleanthes (a metaphysicist with an anthropomorphic conception of God), Demea (mystic). o Even though Philo is a sceptic he shares with Demea a belief in inscrutability of God. Extreme vs. Moderate scepticism (traditional and common sense). - Method: o Cleanthes presents an a posteriori argument for existence of God (argument from design) and Philo critiques it (parts one and two); o Demea presents an a priori argument for existence of God, and Cleanthes and Philo critique it (part nine); o Throughout the text, Hume employs deductive reasoning as well as inductive reasoning in order to multiply potential explanations for the origins of the universe. This leads to a suspension of judgement. Anthropomorphism The representation of Gods, or nature, or non-human animals, as having human form, or as having human thoughts and intentions. – Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy Philo’s (Hume’s) Scepticism “Let us become thoroughly sensible of the weakness, blindness, and narrow limits of human reason: let us duly consider its uncertainty and endless contrarieties, even in subjects of common life and practice: let the errors and deceits of our very senses be set before us; the insuperable difficulties which attend first principles in all systems; the contradictions which adhere to the very ideas of matter, cause and effect, extension, space, time, motion; and in a word, quantity of all kinds, the object of the only science that can fairly pretend to any certainty or evidence. When these topics are displayed in their full light, as they are by some philosophers and almost all divines; who can retain such confidence in this frail faculty of reason as to pay any regard to its determinations in points so sublime, so abstruse, so remote from common life and experience? When the coherence of the parts of a stone, or even that composition of parts which renders it extended; when these familiar objects, I say, are so inexplicable, and contain circumstances so repugnant and contradictory; with what assurance can we decide concerning the origin of worlds, or trace their history from eternity to eternity?” Hume’s Conclusions - There is no world – only individual objects which compose it. - There is no self – only individual perceptions which compose it. - There is no necessary relation between ideas which reflect the objective reality – all our ideas stem from perception and are, consequently, always only related contingently. o The cause-and-effect relation is one of belief and custom: it is itself caused by our experience of observation of cause-and-effect events in the world. o Consequently, there is no metaphysics – all our ideas are strictly based on empirical data and are always related contingently. A priori ideas necessarily connected are always a product of experience and rest on our faith that nature is regular: this faith, however, may or may not be warranted. Argument from Design (Cleanthes) Look around the world; contemplate the whole and every part of it: you will find it to be nothing but one great machine, subdivided into an infinite number of lesser machines, which again admit of subdivisions to a degree beyond what human senses and faculties can trace and explain. All these various machines, and even their most minute parts, are adjusted to each other with an accuracy which ravishes into admiration all men who have ever contemplated them. The curious adapting of means to ends, throughout all nature, resembles exactly, though it much exceeds, the productions of human contrivance; of human designs, thought, wisdom, and intelligence. Since, therefore, the effects resemble each other, we are led to infer, by all the rules of analogy, that the causes also resemble; and that the Author of Nature is somewhat similar to the mind of man, though possessed of much larger faculties, proportioned to the grandeur of the work which he has executed. By this argument a posteriori, and by this argument alone, do we prove at once the existence of a Diety, and his similarity to human mind and intelligence? - An inductive argument (a posteriori) based on observation of nature from which Cleanthes draws three important observations: o Means to ends relation (‘The curious adapting of means to ends, throughout all nature, resembles exactly, though it much exceeds, the production of human contrivance’). o Coherence of parts (‘All these various machines, and even their most minute parts, are adjusted to each other with an accuracy which ravishes into admiration all men who have ever contemplated them’). o Like effects prove like causes (‘Since, therefore, the effects resemble each other, we are led to infer, by all the rules of analogy, that the causes also resemble). Demea’s a Priori Argument “The argument, replied Demea, which I would insist on, is the common one. Whatever exists must have a cause or reason of its existence; it being absolutely impossible for any thing to produce itself, or be the cause of its own existence. It mounting up, therefore, from effects to causes, we must either go on in tracing an infinite succession, without any ultimate cause at all; or must at last have recourse to some ultimate cause, that is necessarily existent: now, that the first supposition is absurd, may be thus proved. In the infinite chain or succession of causes and effects, each single effect is determined to exist by the power and efficiency of that cause which immediately preceded; but the whole eternal chain or succession, taken together, is not determined or caused by any thing; and yet it is evident that it requires a cause or reason, as much as any particular object which begins to exist in time… The question is still reasonable, why this particular succession of causes existed from eternity, and not any other succession, or no succession at all. If there be no necessarily existent being, any supposition which can be formed is equally possible; nor is there any more absurdity in Nothing’s having existed from eternity, than there is in that succession of causes which constitutes the universe. What was it, then, which determined Something to exist rather than Nothing, and bestowed being on a particular possibility, exclusive of the rest? External causes, there are supposed to be none. Chance is a word without a meaning. Was it nothing? But that can never produce anything. We must, therefore, have recourse to a necessarily existent Being, who carries the REASON of his existence in himself, and who cannot be supposed not to exist, without an express contradiction. There is, consequently, such as Being; that is, there is a Deity.” Criticism #1 (Cleanthes) There is an evident absurdity in pretending to demonstrate a matter of fact, or to prove it by any arguments a priori. Nothing is demonstrable, unless the contrary implies a contradiction. Nothing, that is distinctly conceivable, implies a contradiction. Whatever we conceive as existent, we can also conceive as non-existent. There is no being; therefore, whose non-existence implies a contradiction. Consequently there is no being, whose existence is demonstrable. I propose this argument as entirely decisive, and am willing to rest the whole controversy upon it. It is pretended that the Deity is a necessarily existent being; and this necessary of his existence is attempted to be explained by asserting, that if we knew his whole essence or nature, we should perceive it to be as impossible for him not to exist, as for twice two not to be four. But it is evident that this can never happen, while our faculties remain the same as at present. It will still be possible for us, at any time, to conceive the non-existence of what we formerly conceived to exist; nor can the mind ever lie under a necessity of supposing any object to remain always in being; in the same manner as we lie under a necessity of always conceiving twice two to be four. The words, therefore, necessary existence, have no meaning; or, which is the same thing, none that is consistent. Criticism #2 (Cleanthes) In such a chain, too, or succession of objects, each part is caused by that which preceded it, and causes that which succeeds it. Where then is the difficulty? But the WHOLE, you say, wants a cause. I answer, that the uniting of these parts into a whole, like the uniting of several distinct countries into one kingdom, or several distinct members into one body, is performed merely by an arbitrary act of the mind, and has no influence on the nature of things. Did I shew you the particular causes of each individual in a collection of twenty particles of matter, I should think it very unreasonable, should you afterwards ask me, what was the cause of the whole twenty. This is sufficiently explained in explaining the cause of the parts. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) - Born in Konigsberg, Prussia on April 22, 1724. - Claimed that it was David Hume who woke him from his ‘dogmatic slumber’. - Taught at the University of Konigsberg. - He lives a solitary life, often shunning the company of others. Once, when a former pupil tried to bring him out of his isolation, he wrote: ‘Any change makes me apprehensive, even if it offers the greatest promise of improving my condition, and I am persuaded by this natural instinct of mine that I must take heed if I wish that the threads which the Fates spin so thin and weak in my case to be spun to any length. My great thanks, to my well-wishers and friends, who think so kindly of me as to undertake my welfare, but at the same time a most humble request to protect me in my current condition from any disturbance.’ - He was sympathetic to the cause of the French Revolution. - Died in Konigsberg, on April 12, 1804. Kant’s Theory of Knowledge - All out knowledge begins with experience and it can be either: o Analytic (e.g. ‘all bodies are extended’) o Synthetic (e.g. ‘all bodies are heavy’) - Judgements based on experience (a posteriori judgements) are always synthetic. - However, there is such a thing as pure a priori knowledge. Even though it begins with experience, it does not come from it: these are ideas that our ‘faculty of knowledge provides out of itself, with sensible impressions merely prompting it to do this.’ - There are analytic a priori judgements, but is it possible to have synthetic a priori judgements? Kant’s ‘Copernican Revolution’ (Frederic Compleston ‘A History of Philosophy’ Vol VI) “What [Kant] is suggesting is that we cannot know things, that they cannot be objects of knowledge for us, except in so far as they are subjected to certain a priori conditions of knowledge on the part of the subject. If we assume that the human mind is purely passive in knowledge, we cannot explain the a priori knowledge which we undoubtedly possess. Let us assume, therefore, that the mind is active. This activity does not mean creation of beings out of nothing. It means rather that the mind imposes, as it were, on the ultimate material of experience its own forms of cognition, determined by the structure of human sensibility and understanding, and that things cannot be known except through the medium of these forms.” Phenomena and Noumena (The Oxford Companion to Philosophy) “These terms mean literally ‘things that appear’ and ‘things that are thought’… [In Kant’s thought, the] intelligible world of noumena is known by pure reason, which gives us knowledge of things as they are. Things in the sensible world (phenomena) are known through our senses and known only as they appear. To know noumena we must abstract from and exclude sensible concepts such as space and time. Kant called the determination of noumena and phenomena the ‘noblest enterprise of antiquity’, but in the Critique of Pure Reason he denied that noumena as objects of pure reason are objects of knowledge, since reason gives knowledge only of objects of sensible intuition (phenomena). Noumena ‘in the negative sense’ are objects of which we have no sensible intuition and hence no knowledge at all; these are thingsin-themselves. Noumena ‘in the positive sense’ (e.g. the soul and God) are conceived of as objects of intellectual intuition, a mode of knowledge which man does not possess. In neither sense, therefore, can noumena be known. For both Plato and Kant, nevertheless, conceptions of noumena and the intelligible world are foundational for ethical theory.” Antinomy (The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy) “A paradox. In Kant’s first Critique the antinomies of pure reason show that contradictory conclusions about the world as a whole can be drawn with equal propriety. Each antinomy has a thesis and a contradictory antithesis. The first antinomy has a thesis that the world has a beginning in time and is limited in space, and as antithesis that it has no beginning and no limits. The second proves both the infinite divisibility of space and the contrary; the third shows the necessity, but also the impossibility of human freedom and the fourth proves the existence of a necessary being and the lack of existence of such a being. The solution to this conflict of reason with itself is that the principles of reasoning used are not ‘constitutive,’ showing us how the world is, but ‘regulative,’ or embodying injunctions about how we are to think of it. When regulative principles are taken outside their proper sphere of employment, as they are when theorizing about the world as a whole, contradiction results.” Kant’s 4th Antinomy - Thesis: ‘There belongs to the world, either as its part or as its cause, a being that is absolutely necessary.’ o Demea’s a priori proof of God’s existence. - Antithesis: ‘An absolutely necessary being nowhere exists in the world, nor does it exist outside the world as its cause.’ o Cleanthes’s counter-argument.