CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION PRELIMINARY DRAFT

advertisement

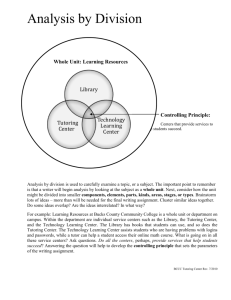

CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Certificate of Recognition: Lessons from Heterogeneous Response to a Randomize Controlled Trial of Nonfinancial Incentives for Student Attendance Brooks Rosenquist & Matthew G. Springer Vanderbilt University, Peabody College Department of Leadership, Policy & Organizations Association of Education Finance and Policy (AEFP) Conference, Spring 2013 Corresponding author: brooks.rosenquist@vanderbilt.edu 1 CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 2 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Certificate of Recognition: Lessons from Heterogeneous Response to a Randomize Controlled Trial of Nonfinancial Incentives for Student Attendance Objectives The 2001 federal No-Child Left Behind Act required districts to make available free after-school tutoring for low-income students attending a Title I school which has failed to make adequate yearly progress towards its accountability goals (Springer, Pepper, Gardner, & Bower, 2009). Evidence of the effectiveness of these programs has ranged from positive to mixed and negligible.1 Despite an apparent potential benefit in some contexts, these “supplementary educational services” are often underutilized by students. Analyzing supplementary educational services in five large school districts, Berger and colleagues (2011) found that on average, only 18 percent of students eligible to participate registered for supplementary services. Of those eligible students who did register, 28 percent never attended one tutoring session. Because participation in this kind of after-school tutoring is voluntary for students, it often competes with other extracurricular activities, and attendance typically declines as the school year progresses (GAO, 2006). Lack of persistence in attendance may be problematic; in a 2012 review of studies of supplementary educational services’ effectiveness in raising individual student test scores, Heinrich estimates that attendance of approximately 40 hours of tutoring may represent a “critical threshold,” below which student gains to achievement test scores are not typically realized. 1 Studies finding positive impacts in mathematics and reading include: Rickles and Barnhart, 2007; Springer, Pepper, Gardner, and Bower, 2009; Zimmer et al, 2006; and Zimmer et al, 2007. Studies with findings of mixed impacts include: Heistad, 2007; and Rickles and White, 2006. Potter et al, 2007 and Heinrich, Meyer, and Whitten, 2007 found negligible impacts. CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 3 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Because tutoring attendance is not mandatory and also presents opportunity costs for students, students registered for these services may respond to some forms of incentives. In the 2009-2010 school year, educational researchers collaborated with a Southern urban school district to conduct a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of incentives on student attendance of supplementary educational services. In this experiment, non-monetary recognition incentives significantly increased attendance of tutoring services, compared to the control group. In the analysis which follows, we attempt to investigate the ways in which the non-monetary incentive influenced attendance of tutoring and how this effect varied across age and gender. Theoretical Framework Systematic Differences in Achievement Motivation: Age and Gender Our investigation of the interplay between age, gender, incentives, and voluntary attendance of tutoring builds on a great foundation of research in the psychology of achievement motivation. This research reveals that there are systematic differences in motivation between students of different ages. Multiple studies suggest that students’ intrinsic academic motivation generally declines as students age (e.g., Eccles, Wigfield, Harold, & Blumenfeld, 1993; Gottfried, Fleming, & Gottfried, 2001; Harter, 1981). When looking specifically at the value students place on academic tasks, researchers have also observed declines as students age (Jacobs et al. 2002; Fredericks & Eccles, 2002). Along with age, gender also seems to be an important variable in predicting students’ motivation in school and response to different incentives. For example, boys are more likely to be labeled as underachievers (McCall, Evahn, & Kratzer, 1992), spend less time on homework (Jacob, 2002) and seem to put forward less effort and create more frequent disruptions than girls CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 4 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME (Downey & Vogt Yuan, 2005). Some research suggests that compared to boys, girls in the educational environment may perceive failure differently and are more motivated by avoiding failure. More specifically, females are more likely to choose easier laboratory tasks, avoid challenging and competitive situations, lower their expectations following failure, switch college majors in response to a decline in course grades, and perform below their ability level on difficult timed tests (Dweck & Licht, 1980; Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999). Some studies suggest that race and gender interact to influence the degree to which students identify with proacademic behaviors. Graham, Taylor, and Hudley’s 1998 study of middle-school students found that while white boys and girls of all races identified high achieving peers as individuals whom they admired, respected, and wanted to be like, African American and Hispanic boys were more likely to report admiring their low-achieving peers. Nonfinancial Incentives Both theory and the literature provide numerous ways to perceive nonfinancial incentives as potentially very effective motivators. Frey (2007) points out that, compared to monetary compensation, awards have the advantage of (1) being less likely to crowd out recipients’ intrinsic motivation than monetary compensation, (2) being more likely to reinforce bonds of loyalty and other positive relationship attributes, and (3) having relatively low material costs for the presenter, especially relative to recipient valuation. Frey also notes that these kind of nonfinancial incentives serve a strong signaling function: the presenter signals the kind of behavior that is desired and valued, and the recipient is able to signal to others the ability and history of displaying these kinds of behaviors. CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 5 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Systematic Differences in Response to Incentives Reviewing previous literature, Levitt and colleagues (2012) note that the patterns of differential response to incentives by gender is mixed in the literature, with girls possibly more responsive to longer-term incentives (Angrist, Lang, & Oreopoulos, 2009; Angrist & Lavy, 2009) and boys perhaps more responsive to short-term incentives, especially when incentives are framed in the context of a competition (Gneezy, Niederle & Rustichini, 2003; Gneezy & Rustichini, 2004). Furthermore Levitt and colleagues (2012) find that both financial and nonfinancial incentives tend to be more effective with younger students compared with older ones. Data In the 2009-2010 school year, researchers working with a Southern urban school district identified 309 students in grades 5 through 8 who were eligible for and registered to receive supplementary educational services. Students were drawn from 14 different schools and attended any of 16 different providers of supplemental educational services. Of these 309 students, three did not meet inclusion criteria, and another four students opted out of participating in the study (see figure 1). Students were assigned to one of three experimental conditions: a control group, a group which would receive monetary incentives for attendance, and a group which would receive symbolic, non-monetary recognition for their attendance. Students offered a non-monetary recognition incentive were told prior to attending tutoring that signed certificates from the superintendent of schools would be mailed to their homes upon completion of 25 percent and 75 percent of their allotted tutoring hours.2 Student attendance in tutoring was monitored from its first episode (taking place as early as October) until the end of Students are allotted different hours of tutoring because providers of supplementary educational services can charge different hourly rates. Tutoring providers invoice the school district for the number of hours students attend, up to a maximum per-student, per-year dollar allocation. 2 CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 6 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME the school year. For the purposes of this paper, results from the monetary incentive treatment group are not addressed in order to focus on the effects of non-monetary recognition. The student sample is limited to middle-school students in grades 5 through 8, although lower grades are over-represented, with 36 percent of the sample in grade 5 and 18 percent in grade 8. Because the supplementary education services target low income students in Title I schools, 97 percent of students in this sample receive free- or reduced-price lunch. 77 percent of students are categorized as African-American or Hispanic. (see Table 1 for complete descriptive statistics and evidence of randomized balance between experimental groups). Methods Because non-attendance of tutoring was a significant phenomenon in these two experimental groups under consideration in this paper, we chose to look not only at the expected hours of tutoring attendance for each group, but decided to decompose this behavior into two components and to examine separately these two behaviors: attendance or non-attendance of tutoring, and persistence in attending tutoring among those who attended at least one tutoring session. Here, the analytical approach might be similar to the evaluation of program aimed at incentivizing college going among high school senior, estimating treatment effects on the outcomes of both college enrollment and college persistence among those who enrolled. In this analysis, we will use the term take-up to describe the attendance of at least one tutoring session among students registered for supplementary educational services; the term persistence will be used to describe the number of hours of tutoring attended by those who registered and attended at least one tutoring session. Accordingly, treatment effects are estimated for three different outcomes, using different models for each: CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 7 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME (1) Total Hours Attendedi = β0 + β1 Certificatei + β2 Paymenti + εi (2) Take-upi = δ0 + δ1 Certificatei + δ2 Paymenti + ε’i (3) 𝑃𝑒𝑟𝑠𝑖𝑠𝑡𝑒𝑛𝑐𝑒𝑖 = (𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝐻𝑜𝑢𝑟𝑠 𝐴𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑛𝑑𝑒𝑑𝑖 | 𝑇𝑎𝑘𝑒­𝑢𝑝𝑖 = 1) = 𝑒 (ζ0 + ζ1 Certificatei + ζ2 Paymenti + ε′′ ) 𝑖 Different regression approaches, however, are applied to the different models because of the distributional characteristics of each outcome variable. Ordinary least squares regressions are applied to the regression models with total hours attended or tutoring takeup3 as dependent variables. The dependent variable of Equation (3), persistence in tutoring attendance, is an overdispersed count variable, and is estimated with negative binomial regression. Results Treatment effects Assignment to the certificate incentive group is associated with greater average hours of attendance, with the treatment group averaging 18.4 hours of tutoring attendance, compared with an expected 5.1 hours of tutoring (p<0.001)4. The certificate incentive is associated with a 15 percentage point increase in tutoring take-up, over and above the 63 percent take-up rate observed in the control group (p=0.02). Excluding the analysis to students attending at least one tutoring session, the certificate incentive is associated with nearly three times the number of tutoring hours, with the expected hours of attendance for those who take-up tutoring to be 23.7 hours for those in the certificate incentive group, compared to 8.1 hours in the control group (p<0.001). 3 Applying OLS regression to a binary dependent variable such as take-up is also referred to as a linear probability model (LPM). 4 See regression results in Table 1 for point and p-value estimates CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 8 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Differential Response by Grade When looking at the differences between average hours attended by grade for all students assigned to treatment and control, there was a significant interaction between treatment and grade, with each additional grade above grade 5 associated with an expectation of approximately 3.0 fewer hours of tutoring attendance (p=0.033) (see table 2). However, this diminishing effect by grade is not isolated or detected after the main effect is decomposed and take-up and persistence effects are analyzed separately. The certificate incentive is associated with greater likelihood of take-up of tutoring services only in students in grade 5 (p-value = 0.004), but is not associated with a greater likelihood of take-up of tutoring service at conventional levels of significance for students grades six through eight. Among those attending at least one tutoring session, the certificate incentive is associated with greater persistence in all grades five through eight. Differential Response by Gender The effect of the certificate treatment on tutoring take-up varied greatly by gender. In the control group, female students registered for tutoring were actually less likely to take-up tutoring than males, with take up rates of 53 and 72 percent, respectively (p-value=0.036). While the certificate is not associated with greater take-up for males, the effect of the certificate incentive on female enrollment appears to be quite large. Only 53 percent of registered females in the control group attended at least one tutoring session, compared to 86 percent of registered females in the certificate group (p=0.003). An investigation of the certificate treatment on persistence reveals higher persistence among registered students for both males and females (p-value less than 0.001 for both). CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 9 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Significance The patterns of heterogeneous response to this application of nonmonetary incentives suggest implications for the design and implementation of student incentive programs more generally. When considering the signaling effect of any incentives – and nonfinancial awards in particular – it may be very important to consider not only the signal given by the award, but also the perceptions and values of the multiple audiences observing the signal. Furthermore, because targets of incentive schemes often respond in systematically heterogeneous ways, incentive schemes are likely to be made more effective through response monitoring, followed by the addition of strategies to target subpopulations and behaviors not sufficiently influenced by the existing incentive structures. Considering the Audience of the Signal When effective, non-monetary recognition incentives present clear advantages: they are less costly and often less controversial than monetary incentives (Levitt et. al. 2012, Frey, 2007). Frey (2007) points out, “Awards certainly represent more than just money, and the recipients experience them as a special form of social distinction, setting them apart from the other employees” (p. 6). However, this feature may subvert the intended effect of nonmonetary awards for academic performance in some contexts. Adolescent students, in particular, may not desire to be “set apart” from other students in general, and may avoid being “set apart” from other students on the basis of superior academic performance, in particular. In general, adolescent students may not respond well to incentives to increase academic behavior, as they may want to seem independent – not compliant – or may belong to a social group which devalues academic performance (NRC, 2003). However, regardless of whether an individual CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 10 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME student personally values academic achievement, an individual’s perception of his or her peers’ disregard for academic achievement may blunt the intended effect of incentives designed to reward students through social recognition. Many adolescent students perceive their peers as discounting academic achievement and pro-academic behavior, such that students might avoid this type of behavior to avoid a loss of status among peers (Arroyo & Zigler, 1995; Fordham, 1996; Fryer & Torelli, 2010; Yonezawa, Wells, & Serna, 2002). In the context of this experiment, the positive effects of the non-monetary incentive may have been realized because of the most proximal audience: because the certificate was mailed home, the signal of this award was observed not by peers, but by the student’s parents and family. If the parent-adolescent relationship is one which can be characterized as exhibiting significant information asymmetry regarding the student’s proacademic values, motivation and behavior, than this award in particular might be viewed signal of a student’s proacademic values and behavior to students’ parents. For some adolescent students, the signal would be particularly efficacious, in that it excludes any similar but undesirable signaling to the students peers. There is evidence to suggest that students would prefer that different audiences receive different signals. Relative to peers, adolescents’ parents place greater value on time spent on homework (Fordham, 1996), are less tolerant of misbehavior in class (Berndt, Miller, & Park, 1989), and place different relative values on reputation, popularity, and academic success (Coleman, 1961). It is likely then that student know or perceive their parents to value academic achievement and behavior – including tutoring attendance – more than are students’ peer groups. For this reason, incentives that aim to generate recognition or pride from a student’s parents might be more effective than those awarded before students’ peers. CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 11 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Monitoring and responding to heterogeneous response to incentives. This study adds to the evidence that suggests that, along with students having systematically different levels of intrinsic motivation, students also respond to incentives in systematically different ways. The finding from this study supports the findings reported by Levitt and colleagues (2012), that the effects of both financial and nonfinancial incentives for students tends to decrease with student age. This study, like others (Angrist et. al, 2009, Angrist & Lavy, 2009, Gneezy, Niederle, & Rustichini, 2003; Gneezy & Rustichini, 2004; Levitt et al, 2012), has also found significant differential effects of incentives by gender. This suggests that incentive systems need to be designed with these systematic differences in mind. Student incentive systems should be actively monitored for results and adjusted or amended according to outcomes. In the context studied in this analysis, male students offered certificates of recognition did not seem to be any more likely to take-up tutoring services than those in the control group, although the certificate did seem to be an effective incentive for encouraging persistence in those male students attending at least one tutoring session. Put another way, males in this sample seemed to need additional support or incentives to take-up tutoring services and “get over the hurdle” of attending tutoring session for the first time. Specifically, by addressing the barriers and incentives to male take-up of tutoring service, the district might expect to leverage the observed persistence-effect of the certificate incentive to an even greater degree. CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 12 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME References Angrist, J., Lang, D., & Oreopoulos, P. (2009). Incentives and Services for College Achievement: Evidence from a Randomized Trial. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(1), 136-163. Angrist, J., & Lavy, V. (2009). The effects of high stakes high school achievement awards: evidence from a randomized trial. The American Economic Review, 99(4), 1384-1414. Arroyo, C.G., and Zigler, E. (1995). Racial identity, academic achievement, and the psychological well-being of economically disadvantaged adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 903-914. Berger, A., deSousa, J-M, Hoshen, G., Lampron, S., Le Floch, K.C., Petroccia, M., Shkolnik, J. (2011). Supplemental Educational Services and Student Achievement in Five Waiver Districts. Washington, DC: US Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development Berndt, T.J., Miller, K.E., and Park, K. (1989). Adolescents’ perceptions of friends’ and parents’ influence on aspects of their school adjustment. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 419-435. Coleman, J.S. (1961). The adolescent society. New York: Free Press of Glencoe. Downey, D.B., & Vogt Yuan, A.S. (2005). Sex differences in school performance during high school: puzzling patterns and possible explanations. Sociology Quarterly 46(2), 299–321. Dweck, C. S., & Licht, B. G. (1980). Learned helplessness and intellectual achievement. In J. Garber & M. E. P. Seligman (Eds.), Human helplessness: Theory and applications. New York: Academic Press. CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 13 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Eccles. J. S., Wigfield, A., Harold, R .. & Blumenfeld, P. B. (1993). Age and gender differences in children’s self- and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development, 64, 830-847. Fordham, S. (1996). Blacked out: Dilemmas of race, identity, and success at Capital High. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Fredericks, J., & Eccles, J. S. (2002). Children's competence and value beliefs from childhood through adolescence: Growth trajectories in two male sex-typed domains. Developmental Psychology 38, 519-533. Frey, B. S. (2007). Awards as compensation. European Management Review, 4(1), 6-14. Fryer, R.G. & Torelli, P. (2010). An empirical analysis of ‘acting white’. Journal of Public Economics 94(5-6), 380-396. Gneezy, U., Niederle, M., & Rustichini, A. (2003). Performance in competitive environments: Gender differences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(3), 1049-1074. Gneezy, U., & Rustichini, A. (2004). Gender and competition at a young age. American Economic Review, 377-381. Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2006). No Child Left Behind Act: Education Actions Needed to Improve Local Implementation and State Evaluation of Supplemental Educational Services. Report 06-758 Washington, DC: Author. Gottfried, A. E., Fleming, J. S., & Gottfried, A. W. (2001). Continuity of academic intrinsic motivation from childhood through late adolescence: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 3-13. Graham, S., Taylor, A. Z., & Hudley, C. (1998). Exploring achievement values among ethnic minority early adolescents. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 606-620. CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 14 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Harter, S. (1981). A new self-report scale of intrinsic versus extrinsic orientation in the classroom: Motivational and informational components. Developmental Psychology, 17, 300-312. Heinrich, C.J. & Burch, P. (2012). The Implementation and Effectiveness of Supplemental Education Services: A Review and Recommendation for Program Improvement. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Policy Research. Heinrich, C.J., Meyer, R.H., & Whitten, G.. (2010). Supplemental education services under No Child Left Behind: Who signs up, and what do they gain? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 32, 273-298. Heistad, D. (2005). Analysis of 2005 supplemental education services in Minneapolis public schools: An application of matched sample statistical design. Minneapolis: Minneapolis Public Schools. Jacob, B.A. (2002). Where the boys aren’t: noncognitive skills, returns to school and the gender gap in higher education. Economics of Education Review 21, 589–98 Jacobs, J., Lanza, S., Osgood, D. W., Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Ontogeny of children's self-beliefs: Gender and domain differences across grades l through 12. Child Development 73, 509-527. Levitt, S.D., List, J.A ., Neckermann, S., Sadoff, S. (2012, June). The Behaviorist Goes to School: Leveraging Behavioral Economics to Improve Educational Performance. (NBER Working Paper No. 18165). Retrieved from the NBER website: http://www.nber.org/papers/w18165 Long, J.S. & Freese, J. (2006). Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 15 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME McCall, R. B., Evahn, C., & Kratzer, L. ( 1992). High school underachievers: What do they achieve as adults? Newbury Park, CA: Sage. National Research Council (2003). Engaging Schools: Fostering High School Students' Motivation to Learn. Washington, DC: National Academies Press Potter, A., Ross, S.M., Paek, J., McKay, D., Ashton, J., and Sanders, W.L. (2007). Supplemental educational services in the State of Tennessee: 2005 - 2006. Center for Research in Educational Policy. Memphis, TN. Rickles, J.H. & Barnhart, M.K. (2007). The Impact of Supplemental Educational Services Participation on Student Achievement: 2005-06. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Unified School District Program Evaluation and Research Branch, Planning, Assessment and Research Division. Rickles, J.H. & White, J. (2006). The Impact of Supplemental Education Services Participation on Student Achievement (Publication No. 295). Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles Unified School District, Program Evaluation and Research Branch, Planning, Assessment, and Research Division. Spencer, S. J., Steele, M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women's math performance. Journal of' Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 4-28. Springer, M.G., Pepper, M.J., Gardner, C., Bower, C.B. (2009). Supplemental Educational Services Under No Child Left Behind. In M. Berends, M.G. Springer, D. Ballou, H.J. Walberg (Eds., 2009). Handbook of Research on School Choice. New York: Routledge. Springer, M.G., Pepper, M.J. &. Ghosh-Dastidar, B. (2009). Supplemental educational services and student test score gains: Evidence from a large, urban school district. Working paper, Vanderbilt University CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 16 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Yonezawa, S., Wells, A., and Serna, I. (2002). Choosing Tracks: “Freedom of choice” in detracking schools. American Educational Research Journal, 39, 37-67 Zimmer, R., Christina, R., Hamilton, L.S., and Prine, D.W. (2006). Evaluation of Two Out-ofSchool Program in Pittsburgh Public Schools: No Child Left Behind's Supplemental Educational Services and State of Pennsylvania's Educational Assistance Program. RAND Working Paper. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Zimmer, R., Gill, B., Razquin, P., Booker, K., Lockwood, J.R., Vernez, G., Birman, B.F., Garet, M.S., and O'Day, J. (2007). State and Local Implementation of the No Child Left Behind Act: Volume I - Title I School Choice, Supplemental Educational Services, and Student Achievement. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Available at http://www.rand.org/pubs/reprints/2007/RAND_RP1265.pdf. CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 17 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Tables and Figures Enrollment Figure 1. Flow diagram of the progress through the phases of the parallel randomized trial of three groups. Assessed for eligibility (n=309 ) ↓ Randomized (n=309) Analysis Follow-up Allocation ↓ Control Group Allocated to control group (n=103) Declined to Participate (n=1) Not meeting inclusion criteria (n=0) Received allocated intervention (n=0) Did not receive allocated interventions (n=0) ↓ Treatment Group: Certificate Incentive Allocated to intervention (n=106) Declined to Participate (n=3) Not meeting inclusion criteria (n=0) Received allocated intervention (n=0) Did not receive allocated interventions (n=0) ↓ Treatment Group Payment Incentive Allocated to intervention (n=100) Declined to Participate (n=0) Not meeting inclusion criteria (n=3) Received allocated intervention (n=0) Did not receive allocated interventions (n=0) Lost to follow-up (n=0) Discontinued intervention (n=0) Lost to follow-up (n=0) Discontinued intervention (n=0) Lost to follow-up (n=0) Discontinued intervention (n=0) Analyzed (n=102) Excluded from analysis (n=0) Analyzed (n=103) Excluded from analysis (n=0) Analyzed (n=96) Excluded from analysis (missing background variables) (n=1) CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 18 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Table 1. Descriptive variables for combined, control, and certificate treatment groups, randomization balance check between control and treatment groups (1) (2) (3) (4) Groups 1 & 2 Group 1: Control Group 2: T test equal means Certificate b/se b/se b/se p-value White 0.23 0.18 0.20 0.469 0.04 0.04 0.03 AfricanAmerican 0.49 0.05 0.58 0.05 0.54 0.03 0.187 Hispanic 0.25 0.04 0.22 0.04 0.24 0.03 0.598 Asian 0.03 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.310 Female 0.48 0.05 0.55 0.05 0.52 0.03 0.298 FRPL Status: Reduced Lunch 0.09 0.03 0.06 0.02 0.07 0.02 0.412 FRPL Status: Free Lunch 0.87 0.03 0.91 0.03 0.89 0.02 0.356 SPED 0.21 0.04 0.16 0.04 0.18 0.03 0.349 ELL 0.25 0.04 0.20 0.04 0.23 0.03 0.387 Grade 5 0.38 0.05 0.37 0.05 0.38 0.03 0.844 Grade 6 0.24 0.04 0.27 0.04 0.25 0.03 0.550 Grade 7 0.16 0.04 0.23 0.04 0.20 0.03 0.171 Grade 8 0.23 0.04 102 0.13 0.03 103 0.18 0.03 205 0.062 N CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 19 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Table 2: Regression estimations, treating grade as a categorical variable Take-up: Total hours attended: Among all enrollees, total hours of Proportion of enrollees attending at tutoring attended least one hour of tutoring (OLS Regression) (OLS/LPM Regression) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Certificate 13.28*** 1.56 8.86*** 2.22 17.24*** 2.51 0.15* 0.06 -0.04 0.09 0.30* 0.10 Persistence: Among attendees, average hours of tutoring attended (Negative binomial regression) (7) (8) (9) 1.07*** 0.12 0.92*** 0.17 Female -2.90 2.18 -0.19* 0.09 -0.29 0.19 female x Certificate 8.38** 3.08 0.37** 0.12 0.35 0.24 1.05*** 0.18 grade 6 -0.86 2.86 0.25* 0.12 -0.57* 0.22 grade 7 3.98 3.27 0.09 0.13 0.44 0.25 grade 8 -1.33 2.90 0.07 0.12 -0.43 0.24 grade 6 x Certificate -3.60 3.96 -0.31 0.16 0.42 0.28 grade 7 x Certificate -10.64 4.35 -0.26 0.18 -0.56 0.32 grade 8 x certificate -7.18 4.57 -0.14 0.19 0.04 0.33 intercept N R-squared 5.11*** 1.10 205 0.263 6.50*** 1.51 205 0.292 4.99*** 1.76 205 0.303 0.63*** 0.04 205 0.027 0.72*** 0.06 205 0.068 0.54*** 0.07 205 0.060 2.10*** 0.09 144 0.043 (pseudo) 2.20*** 0.12 144 0.046 (pseudo) 2.23*** 0.15 144 0.052 (pseudo) CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION 20 PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Table 3: Regression estimations, treating grade as a continuous variable Take-up: Total hours attended: Among all enrollees, total hours of Proportion of enrollees attending at tutoring attended least one hour of tutoring (OLS Regression) (OLS/LPM Regression) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) certificate 13.28*** 1.56 8.86*** 2.22 16.60*** 2.23 0.15* 0.06 -0.04 0.09 0.22* 0.09 Persistence: Among attendees, average hours of tutoring attended (Negative binomial regression) (7) (8) (9) 1.07*** 0.12 0.92*** 0.17 female -2.90 2.18 -0.19* 0.09 -0.29 0.19 female x certificate 8.38 3.08 0.37** 0.12 0.35 0.24 1.13*** 0.17 grade - 5 -0.00 0.92 0.02 0.04 -0.03 0.08 grade - 5 x certificate -2.97* 1.39 -0.07 0.06 -0.07 0.11 intercept N R-squared * 5.11*** 1.10 205 0.263 6.50*** 1.51 205 0.292 p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 5.11*** 1.57 205 0.293 0.63*** 0.04 205 0.027 0.72*** 0.06 205 0.068 0.61*** 0.06 205 0.034 2.10*** 0.09 144 0.043 (pseudo) 2.20*** 0.12 144 0.046 (pseudo) 2.14*** 0.14 144 0.059 (pseudo) CERTIFICATE OF RECOGNITION PRELIMINARY DRAFT – PLEASE DO NOT CITE – COMMENTS WELCOME Figure 2: Main and Heterogeneous Treatment Effects 21