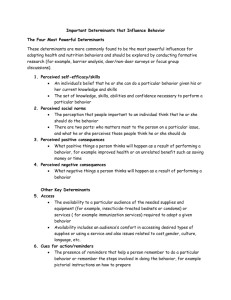

Table 1. Near here

advertisement

Surveying FIFA instructors' behavioral intention towards the Multimedia Teaching Materials M. Armenteros a,*, Shu-Sheng Liawb, M. Fernández a, R. Flores Díaz c, R. Arteaga Sánchez d a Journalism and Audiovisual Communication Department, Carlos III University, C/Madrid 133, 28903 Getafe, Spain b General Education Center, China Medical University, 91 Shiuesh Road, Taichung 404, Taiwan, ROC c Statistics Department, Carlos III University, C/Madrid 133, 28903 Getafe, Spain d Department of Financial Economics and Accounting, University of Huelva, Pza. Merced 11, 21002 Huelva, Spain Abstract Instruction delivered via multimedia applications is changing the way elite football refereeing instructors teach the Laws of the Game. Although e-learning applications are popular, there is minimal research on instructors’ attitudes toward these teaching materials. The purpose of this research is to explore instructors’ behavioral intentions towards the Multimedia Teaching Materials usage. Accordingly, a questionnaire based on an integrated theoretical framework has been delivered to 100 instructors from different FIFA federations. Three main streams of research provide the basis for this framework: the Technology Acceptance Model, the Motivational Model and the Social Cognitive Model, combined with other variables used in educational technology acceptance research. Perceived usefulness, followed by perceived enjoyment, perceived ease of use and the multimedia instruction quality explain most of the instructors’ behavioral intention to use the Multimedia Teaching Materials. 1 Keywords Multimedia Teaching Materials, Technology Acceptance Model, Motivational Model, Behavioral Intention, Refereeing, FIFA. 1. Introduction Professional Training and Development of FIFA referees with New Technologies The use of information and communication technologies as teaching tools has spread into many different areas. This technology-based teaching across organizations has been termed e-learning, which can be designed, developed, and delivered via computer and Internet-based applications (Clark & Mayer, 2011; Horton, 2006).E-learning provides employees with an opportunity to learn in a self-paced and interactive way, regardless of where they are and when they are available. Among FIFA employees, instruction delivered via all electronic media such as the Internet or hypertext/hypermedia documents is changing the way elite football referees teach and learn the Laws of the Game and related matters. FIFA has established a global structure with regional instructors to conduct a continuous follow-up of the daily training of referees and assistant referees at national and international level, and 209 member associations around the world benefits from specialized referee training courses conducted by FIFA. Through the Member Association Referee Courses (MA Referee Courses), FIFA develops regional and international refereeing courses and seminars for 2 its six federations (AFC, CAF, CONCACAF, CONMEBOL, OFC and UEFA) in order to teach in several areas: technical, methodological (uniformity on the interpretation of Laws of the Game), fitness (to improve the quality of the physical instructors) and administrative (refereeing organization development programs). The Refereeing Assistance Programme (RAP) focuses on the education of referee instructors and technical experts actively involved in the instruction of member associations’ top referees and assistant referees both before and after the courses they deliver. The RAP has two main activities: FUTURO III courses for referee instructors and member association courses for top referees and assistant referees (Fédération Internationale de Football Association, 2010) and allows courses to be held almost on a daily basis all over the world, ensures that the match officials in all member associations have adequate preparation. Therefore the RAP instructors constitute the elite of FIFA’s professional training and development chain. They teach other instructors who will then teach international referees all over the world in order to achieve uniformity when applying the Laws of the Game.Since 2005, multimedia interactive materials (from now on Multimedia Teaching Materials, MTM) have been produced by FIFA’s Refereeing Department and Carlos III University’s research group TECMERIN. Both instructors (as teachers) and referees (as learners) have worked on content production while multimedia experts have integrated this content into applications according to instructional design principles and guidelines developed from empirical experiments (Mayer, 2005). These materials allow the students and instructors to interact with different media types and forms (texts, images, videos, animations, sounds) and provide immediate feedback to user decisions. The main MTM applications are: Trivia Game (Armenteros, Benítez & Curca, 2010): This model allows instructors and referees to assess their knowledge with a computer-based quiz. It loads 20 random 3 questions from over 1,500 questions stored in a database. The player must choose the level of difficulty (beginner or advanced) and answer the questions in a 15 minute session. Each time the player chooses an answer the application gives immediate feedback and tells the player if her/his answer is right or wrong. After answering 20 questions, a report appears with the selected answers, the correct and the incorrect ones. Interactive Video Test (Armenteros, Benítez & Sillero, 2009): This consists of an evaluation test with 20 questions about game situations that appear in video clips from several football tournaments. For each clip, the application shows a window where the student must answer whether a foul has been committed or not, as well as indicate the gravity of the infraction (no card, yellow card or red card). After doing the same task for the 20 clips, a report appears with the selected answers, the correct and the incorrect ones. Analysis of Match Situations: Once the student has worked with several Video Test Sessions, he can obtain more information about the match situations with a complementary application: the Analysis of Match Situations. This application shows each clip accompanied by several tabs. When selected, each tab opens a window with extra information regarding the decision the referee should apply, the reasons why this decision is correct, the considerations to take into account when such a match situation occurs, and the reference to the Laws of the Game where more content can be consulted. Teaching Material (Armenteros & Curca, 2008): This application presents the content of the Laws of the Game book in a hypermedia format. Apart from text and static images (that are present in the book), the Teaching Material provides examples of different gaming situations with animations and videos, as well as a self-evaluation with immediate feedback for each law consulted. 4 The purpose of delivering these materials to instructors is to allow them to develop their courses by showing different refereeing situations through videos, animations and images, as well as allowing the instructors to evaluate learners’ knowledge and judgments in real time through several auto evaluation and quiz systems. Some of these materials have already been evaluated among referees as a learning tool (Armenteros, Benítez & Curca, 2010), but nothing has been done as of yet regarding instructor experiences with MTM as a teaching tool. This research aims to achieve deeper knowledge about instructor behavioral intentions to use MTM. To achieve the research objectives, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989), the Motivational Model (MM) (Davis, Bagozzi & Warshaw, 1992) and the Social Cognitive Model (Bandura, 1977), combined with other variables used in educational technology acceptance research (Liaw, Huang & Chen, 2007; Lee, Cheung & Chen, 2005) have been employed. The paper is structured as follows: we begin with a review of the literature as a way of introducing TAM, MM, SCT and other variables employed in previous research on educational technology. We then develop the acceptance model and present our hypotheses, followed by a description of our data gathering technique. We show the results of our statistical analysis and reevaluate the hypotheses. Finally, we discuss the results and the model’s limitations, and offer ideas for future lines of investigation. 2. Literature Review Although research about e-learning acceptance has been carried out extensively, there are no studies regarding the acceptance and behavioral intention of this kind of technology among FIFA instructors. 5 The purpose of new technology usually is improving performance conditions and productivity in a workplace (Yoo, Han & Huang, 2012). Unfortunately, the opportunity for better performance is lost when the technology is rejected by the user. Thus, user acceptance is the main factor determining the failure or success of a technology (Davis, 1993). When trying to understand the user’s behavior toward information technologies, several theoretical models have been developed. Venkatesh, Morris, Davis & Davis (2003) bring together the main influential models concerning IT usage and its acceptance (Table 1). Table 1. Near here This study employs a model based on the Theory of Acceptance Model with the aim of investigating the factors behind the behavioral intention to use Multimedia Teaching Materials. The model provides a stable and secure way to predict user acceptance of a wide range of new technologies. Over time educational technology researchers have extended Theory of Acceptance Model generally by introducing factors from related models. In this respect, core constructs from the Motivational Model (Liaw et al., 2007) and Social Cognitive Theory (Sánchez & Hueros, 2010) have been used. 2.1. Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) Davis’ Technology Acceptance Model (from now on TAM) (Davis, 1989) is designed to predict and explain why a particular system may be unacceptable and in this way identify which changes have to be made in that system. It provides a basis for tracing 6 the impact of external factors on internal beliefs and intentions (Davis, Bagozzi & Warshaw, 1989). Originally (Fig. 1), this model showed the latent causal relationships that exist between perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, external variables, attitude towards system use, behavioral intention and actual system use. Fig 1.Near here Perceived usefulness (PU) measures how people believe their productivity and effectiveness can be improved as a result of using a technology (Davis, 1989). Perceived ease of use (PEU) is the degree to which people believe using a particular system will involve no additional physical or mental effort. Davis (1989) suggests perceived ease of use directly affects perceived usefulness, but not vice versa. If a user works more productively because of a technology that is perceived as easy to use, the user will also perceive that the technology is useful. External variables would also have an influence on behavioral intention indirectly through perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. Regarding the comparison between TAM and TRA, Davis et al., (1989) state that variables such as system design characteristics, user characteristics (including cognitive style and other personality variables), task characteristics, nature of the development or implementation process, political influences or organizational structure would fall into this category. Although the primary interest in their study was to examine the ability to predict and explain user behavior with TAM, they included external variables in their model explaining that one of its purposes was also to provide a foundation for studying the impact of external variables on user behavior. 7 Attitude is the degree to which a user is interested in a system, and has a direct effect on the intention to use that system in the future. Behavioral intention (BI) is the major determinant of usage behavior and the main factor determining a system’s success. In Davis’ original TAM, behavioral intention is supposed to be affected by attitude towards use, as well as by direct and indirect perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use effects. As a result of the use of this model, Davis et al., (1989) concluded that the effect of attitude was only modest in predicting technology acceptance and that individuals may use a technology even if they did not have a positive attitude toward technology per se, as long as it is perceived to be useful and/or easy to use in ways that enhance productivity. In this respect, Mathieson (1991), cited in Teo & Noyes (2011), suggested that eliminating attitude would not significantly lower the predictive capability of the TAM. Thus, TAM excludes the attitude construct in order to explain Behavioral Intention more parsimoniously. This model, both as Davis (1989) proposed and with some variations, has been applied in different environments in recent decades: electronic mail systems, graphic edition software (Davis, 1989), electronic commerce (Pavlou, 2003), virtual worlds (Fetscherin & Lattemann, 2008) and streaming music consumption (Deniz, 2010). Some research states that TAM is a valid model when extended to multimedia and e-learning context (Saadé, Nebebe & Tan, 2007). It has been applied to measure user acceptance of new technology in educational contexts, such as Moodle (Sánchez & Hueros, 2010) computer introduction in classrooms (Teo, Lee & Chai, 2008), web-based collaborative learning systems (Liaw et al., 2007) and interaction modes in learning environments (Davis & Wiedenbeck, 2001). 2.2 Motivational Model 8 The Motivational Model states that system acceptance depends both on extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Extrinsic Motivation Motivation is concerned with related behavior that arises in response to something apart from its own sake, such as reward or recognition means the decision to use a particular technology or system is determined partially by calculation of the benefits. Both perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use have been labeled as extrinsic motivations (Teo, Lim & Lai, 1999). Nevertheless, there can be other kinds of factors that affect the attitude and intentions to use a system. As new information technologies tend to use multiple media and rich graphical interfaces, individual interaction with the technology becomes an increasingly engaging experience (Agarwal & Karahanna, 2000).Following Agarwal & Karahanna it is necessary to pay attention to non instrumental variables. Intrinsic Motivation In this regard, the decision to use a system could also be determined by intrinsic motivation, which refers to the fact of doing an activity for its own sake: the activity itself is interesting, engaging and satisfying (Lee et al., 2005).In a review of TAM, Davis, Bagozzi & Warshaw (1992) took into account the Motivational Model, and added perceived enjoyment (PE), stating that intrinsic motivations are also predictors of behavioral intention to use a system. Perceived enjoyment (PE) is defined as the degree to which the activity of using a technology is perceived to be enjoyable in its own right apart from any performance consequences that may be anticipated (Davis, et al., 1992). Some other researchers have also hypothesized the perceived enjoyment as a factor determining the use of IT 9 (Igbaria, Schiffman & Wieckowski, 1994), especially with systems related to hedonic activities (Chesney, 2006; Van der Heijden, 2004). In regard to educational technology, this variable has been examined by Teo & Noyes (2011), Liaw et al., (2007) and Lee et al., (2005). 2.3 Social Cognitive Theory Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1977) is an empirically validated model of individual behavior. It states that environmental influences (such as social pressure), cognitive and other personal factors (such as personality or demographic characteristics) and behavior are reciprocally determined. Compeau & Higgins (1995) apply this model to computer utilization through the parsimonious examination of the variable perceived self efficacy (PSE). These authors define perceived self efficacy as people's judgments of their capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to attain designated types of performances. This model is concerned not with the skills one has but with judgments of what one can do with whatever skills one possesses (Bandura, 1986, cited in Compeau & Higgins, 1995). 2.4 External variables As previously stated, TAM has also been used to assess the role of external variables, such as system features and user characteristics, as determinants of the behavioral intention through the key beliefs (perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use). Some of these external variables added to the TAM model are: 10 Multimedia instruction (MI): This is concerned with the instructor’s attitudes towards the possibility of explaining concepts and processes by pictures (both static and dynamic), as well as the affordance of assessing their pupils’ knowledge in real time through quizzes and auto-evaluations. The implementation of these features in the design of teaching materials involves higher costs than does development of traditional materials such as textbooks. Is it really worth producing MTM? Do instructors value them in a significant way? As for the quality of e-learning environment, instructors believe that both system satisfaction and multimedia instruction are vital factors (Liaw et al., 2007). Previous experience with IT (PET): This is concerned with the previous use people have made of technological applications and tools. Previous experience can be a significant predictor of behavior toward a system (Taylor & Todd, 1995). 3. Research model and hypotheses This work proposes a tool to measure FIFA instructors’ acceptance and behavioral intentions towards MTM. It also aims to offer ideas to study football instructors’ acceptance and use intention towards multimedia teaching material in order to improve the MTM which are currently being developed for Futsal and Beach Soccer Referees. 3.1 Design Based upon the foregoing theories, we propose our research model in Figure 2. 11 Fig 2. Near Here Some variables considered in previous research related to educational technology have been taken into account for our purposes. Specifically, apart from perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use (hypothesized to be the main factors determining user acceptance and behavioral intention by Davis (1989), we introduce an intrinsic variable (perceived enjoyment), a variable from the social cognitive theory (self efficacy), a variable regarding the system characteristics (multimedia instruction) and a variable that deals with instructor’s characteristics (experience in IT use, labeled as external variables). 3.1.1 Perceived usefulness In regard to MTM, perceived usefulness reflects the degree to which instructors believe that using MTM can make them work more efficiently, easily and with better results. Apart from being the main influence on system use according to Davis (1989) and Davis et al., (1992), perceived usefulness was a great predictor of the intention to use elearning technology among instructors (Liaw et al., 2007), academicians (Tarcan, Varol & Toker, 2010) and pre-service teachers (Teo et al., 2008). Thus, we propose that: H1: The perceived usefulness (PU) of Multimedia Teaching Materials influences positively and directly the behavioral intention (BI) to use the system. 3.1.2 Perceived Ease of Use As far as MTM is concerned, perceived ease of use is the degree to which instructors believe working with MTM does not require additional physical or mental effort while allowing them to reach their teaching goals in an easy way. As hypothesized in the original TAM model, perceived ease of use of learning technologies had a direct positive effect on perceived usefulness (Teo et al., 2008), and 12 had a mediating impact on the intention to use a system through perceived usefulness among academicians (Tarcan et al., 2010).We then propose: H2: The perceived ease of use (PEU) influences positively and directly perceived usefulness (PU). 3.1.3 Perceived Enjoyment Perceived enjoyment is concerned with how instructors believe teaching with MTM is a satisfying, exciting and enjoyable activity. When taking into account intrinsic motivation variables such as perceived enjoyment, it has been found that this variable plays a significant role in the user’s technology acceptance. Davis and colleagues’ findings (Davis et al., 1992) indicate that people’s intentions to use computers in the workplace are influenced mainly by their perceptions of how useful the computers are for improving their job performance, and secondarily by the degree of enjoyment they experience in using the computers per se. In addition, both perceived usefulness and perceived enjoyment fully mediate the effects on usage intentions of perceived ease of use. Similarly, and with respect to educational technology, Lee et al., (2005) showed that both perceived usefulness and perceived enjoyment played an important role in affecting student attitude and intention to use internet-based learning media. In the context of the MTM, we can therefore postulate a positive relationship between perceived enjoyment and intention to use MTM. Thus, the third hypothesis is stated as follows: H3: The perceived enjoyment (PE) of Multimedia Teaching Materials influences positively and directly the behavioral intention (BI) to use the system. 13 When compared with other research results, relationships between perceived enjoyment and other variables are different depending on the context (Venkatesh, 2000). Venkatesh found that enjoyment in different systems (an interactive online help desk system, a multimedia system for property management and a PC-based environment for a company payroll application) affected directly the perceived ease of use. That relationship got stronger with increasing direct experience with the target system over time. Similarly, Teo et al.,(2011) found that perceived enjoyment had a significant direct influence on intention to use technology, as well as on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use among pre-service teachers. That encourages us to propose: H4: The perceived enjoyment (PE) of Multimedia Teaching Materials influences positively and directly Perceived Usefulness (PU). H5: The perceived enjoyment (PE) of Multimedia Teaching Materials influences positively and directly Perceived Ease of Use (PEU). While Teo et al., (2011) and Venkatesh, Speier & Morris (2002) state that perceived enjoyment influences perceived ease of use, other researchers state that it is perceived ease of use which influences perceived enjoyment among undergraduate students (Lee et al., 2005) and internet users (Teo et al., 1999). 3.1.4 Multimedia Instruction Multimedia instruction (MI) tries to assess how the interplay between media richness and immediate feedback improves instructor’s intention to use teaching materials. Precisely, it could identify instructors’ beliefs about showing different match management situations and referees’ techniques by means of videos, animations, images and sounds, as well as testing their pupils with applications such as Video-test, Trivia and Auto-evaluation. 14 According to Liu, Liao & Pratt (2009) materials that implement media richness are more accepted among students, since they stimulate perceived usefulness and concentration. In the study by Liaw et al., (2007) instructors considered that multimedia instruction is a vital factor determining the quality of an e-learning environment. It is also a predictor of perceived enjoyment. These results encourage us to propose: H6: The quality multimedia instruction (MI) of MTM influences positively and indirectly Behavioral Intention (BI) through perceived usefulness (PU). H7: The quality multimedia instruction (MI) of MTM influences positively and directly the perceived enjoyment (PE). 3.1.5 Previous experience with IT In the context of MTM, Previous experience with IT (PET) labels the instructors’ previous experience in working with hypermedia and multimedia systems, such as Power Point, or different platforms (PC, Mac, iPhone). Regarding previous experience with technology, Taylor & Todd (1995) stated there may be differences between experienced and inexperienced users in the relative influence of various determinants of IT usage, such as ease of use and perceived usefulness. Users without experience may focus first on ease of use. With experience, users may overcome concerns about ease of use and may focus their attention on perceived usefulness. This suggests that the path from ease of use to a positive attitude will be stronger for inexperienced users, while the path from perceived usefulness to a positive attitude will be stronger for experienced users. As MTM are relatively new among the teaching materials that instructors use, it is presumed that previous experience with hypermedia and similar technologies can influence the way they regard their easiness and usefulness. We consider that more 15 experienced instructors will value MTM as easier to use and more useful. The consequent hypotheses are: H8: Previous experience with technology (PET) influences positively and directly perceived ease of use (PEU). H9: Previous experience with technology (PET) influences positively and directly perceived usefulness (PU). 3.1.6 Perceived Self-efficacy Perceived self-efficacy represents intructors’ perceptions of their ability to use these materials in the accomplishment of their courses. In regard to MTM, it represents intructors’ perceptions of their ability to use multimedia technology in the accomplishment of a task. As far as perceived self-efficacy is concerned, Albion’s study (2001) showed that selfefficacy was the key to explaining teachers’ use of technology for teaching in the classroom. According to the study by Liaw et al (2007), instructors have highly positive attitudes toward e-learning that included perceived self-efficacy, enjoyment, usefulness, and behavioral intention of use. When understanding instructors’ behavioral intention to use e-learning environments, perceived usefulness is the greatest contributor (56%) and perceived self-efficacy has a contribution of 21%. As far as self efficacy is concerned, we expect that instructors who feel confident when teaching with the MTM will consider these materials more useful. Thus we have: H10: Perceived self-efficacy (PSE) influences positively and directly behavioral intention (BI) to use MTM. 3.1.7 Behavioral Intention 16 Behavioral intention (BI): This is the dependent variable and the one we wish to measure, i.e., the degree to which FIFA football instructors will want to use MTM. A summary of the hypotheses is provided in Figure.3. Fig 3. Near here 4. Research method 4.1- Development of instruments Data were collected through a questionnaire administered to instructors among the different FIFA federations. The first part of the questionnaire gathers information about participants, such as sex, age and years of experience as an instructor. The second part has 43 items where participants are asked to indicate their perceptions and beliefs toward MTM. For these 43 questions a numerical ten-point scale was used. We found that scale clear enough to show the results regarding the contrasts between variables, and that it is especially intuitive for those surveyed, who usually see this type of range of punctuation in other questionnaires. Before the questionnaire was distributed, a provisional version was developed in order to test the validity and accuracy of the questions. This questionnaire was used during a FIFA course in Cuba with five international instructors and it was concluded that the items were well understood and that they did not lead to different interpretations. 17 The questions were based mainly on items Davis employed in his first TAM (1989, for Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use variables) and items obtained from similar research (for MI, PSE, PET and PE, in Liaw et al. 2007). These items were adapted both to specific features of MTM and to our knowledge about the use instructors make of these materials. 4.2- Sample and data collection A total of 100 instructors from the six FIFA confederations were invited to participate in the research. Questionnaires were sent to each confederation’s coordinator, who distributed, collected and sent them back to the research group without personal data of those surveyed (so as to guarantee respondents’ anonymity ). A total of 92 out of 100 questionnaires were finally collected, and 88 of them were marked as valid. The other 4 were rejected because of incomplete or incorrectly stated answers.) As a method for assessing the collected data, a multiple linear regression model was applied. Through regression it is possible to find the relationships between independent variables PEU, PSE, PE, PU, Mi and PET and the dependent variable (BI). These variables are defined as aggregates of the multiple sub-variables defined in Annex A. We performed independent regressions to test the individual influence, and we aggregate different groups of these variables to test their joint influence. As a result, we obtained two different models which together explain a large part of the behavior intention we intended to study. 5. Analysis and Results 18 The Cronbach’s alpha reliability test on instructors’ behavioral intention toward Multimedia Teaching Materials was to be highly accepted (α = 0.960). The high alpha reliability gives a support for questionnaire content reliability (Annex B). When modeling the sub-variables as a function of the explanatory variables, it can be seen that only four of the 38 (Var32, Var50, Var70 and Var73) give rise to a p-value which is less than 0.05 in the estimation of the regression coefficient (Table 2). Table 2. Near Here Inside every group of variables (PET, PEU, PSE, PE, PU and MI) every sub-variable contained essentially the same information, so it was more practical to obtain the appropriate measures by grouping the sub-variables in “global” variables (1-PET, 2PEU, 3-PSE, 4-PE, 5-PU y 7-MI) where the repeated information was erased. The values of the global variables then become the averages of the values of the corresponding sub-variables , with one exception: sub-variables 26, 27 and 32 model a question concerning a negative feature of the tests, so when computing the average we modify them by taking (10-Variable 26), (10-Variable 27) and (10-Variable 32). Once we defined the new global variables, we test their influence on the behavior. First, individual linear regressions were performed, whose coefficients and significance are resumed in Table 3. Table 3. Near Here 19 All the p-values are smaller than 0.01, which indicates a strong relation between BI and any of the other variables, when these are taken separately. Regression coefficients, which show the magnitude of the dependence, are also shown in Table 3. To obtain a more complete model, we undertake a multiple regression of the aggregate dependent variable with respect to the aggregate independent variables. However, if we perform the regression with regard to all the independent variables, some multicollinearity appears. The results of this estimation are shown in Table 4, and from there it must be inferred that the only variable which influences BI in an independent way is PU (p-value=0.00), the perceived usefulness. So the user, taking into account the utility that he/she perceives, carries out behavior which does not depend on the influence of the other variables. Table 4. Near Here To obtain a precise model, and complete the information contained in the variable PU, we have tested some different groups of variables which may help to predict future behavior (BI). After a number of estimations which combined different groups of variables (and whose results are available upon request) we obtained two different regressive models which avoid in a significant way the multicollinearity problem; the first of them models BI in terms of PE and PU, while the second takes PU, PEU and MI as explanatory variables. As we see below, the two models are complementary. The first one is: 1) BI= 2-7796+0.152PE +0.573PU + e 20 The global p-value of the multiple regression is 0.000 here, while the p-values for the correspondent coefficients are 0.055 (PE) and 0.000 (PU); this offers a good level of significance both globally and individually. Moreover, the coefficient of determination is 0.503, and so more than half of the behavior of BI is explained by these variables. The behavior intention grows rapidly in terms of the perceived usefulness, and a bit slower in terms of the enjoyment which the learning method provides to the user. 2) BI= 4.422+0.237PU+0.161MI+0.547PEU+ The global p-value turns out again to be 0.000, and the individuals ones 0.030, 0.048 and 0.079, each of them below the level 0.1. The coefficient of determination is 0.359, so these variables explain an important part of BI. Note that again PU gives rise to a stronger increasing of the behavior intention, while the effect of the perceived ease of use and the multimedia instruction, though smaller, is still significant. The regression of PU on MI and PEU, which is again significant, gives rise to a coefficient of determination of 0.462. In this way we can infer that more than half of the information of BI, which linearly depends on MI and PEU, does not depend on PU, and hence is uncorrelated with it. The two proposed models, considered together, offer an accurate estimation of which are the relevant variables that influence the behavior intention, and how they do it. Although this research proposes behavioral intention (BI) as the dependent variable, with the other ones being labeled as independent variables, the literature review has led us to propose some hypotheses that attempt to discover possible influences from perceived enjoyment (PE), previous experience with technology (PET) and multimedia instruction (MI) on variables that are not behavioral intention (BI). 21 Thus, we have carried out several individual regressions so as to see the influence of perceived enjoyment (PE) on perceived usefulness (PU) (on the one hand) and on perceived ease of use (PEU) (on the other hand); the influence of previous experience with technology (PET) on perceived usefulness (PU) and, separately, on perceived ease of use (PEU); and finally, the influence of multimedia instruction (MI) on perceived enjoyment (PE). Perceived enjoyment’s (PE) influence on perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEU) are estimated through two regressive models: PU=0.504PE+4.280 PEU=0.690PE+1.733. For the first model, both the intercept and the slope are significant (p-value=0.000) and the correlation coefficient is 0.64. For the second, the slope is significant at any level (p-value=0.000), the intercept is thus for =0.05 (p-value=0.025): and the correlation coefficient is 0.655. Regarding the previous experience with technology’s (PET) influence on perceived usefulness (PU) and on perceived ease of use (PEU), we obtain the next two regressive models: PU=0.1741PET+7.339 PEU=0.429PET+4.356 Again here the two slopes are significant at any level (p-value=0.000), and the correlation coefficients are respectively 0.246 and 0.457. Finally, the multimedia instruction’s influence on perceived enjoyment is assessed through the following model: PE=0.538MI+4.220. 22 The correlation coefficient is 0.566 and the p-values are 0.That means there is a high influence of multimedia instruction on perceived enjoyment. 6. Discussion When joining PU and PE according to the first regressive model (BI= 2.779+0.152PE +0.573PU + ), more than half of the Behavioral Intention is explained by these two variables. Therefore, H1 and H3 are true. Behavioral Intention towards the use of MTM would grow mainly because of the Perceived Usefulness of the system and, to a lesser extent, the Perceived Enjoyment. This is consistent with previous studies regarding the influence of perceived usefulness and perceived enjoyment on behavioral intention (Davis, 1989; Davis et al., 1992; Liaw et al., 2007, Tarcan et al., 2010 and Teo et al., 2011). From the second regressive model (BI= 4.422+0.237PU+0.161MI+0.154PEU+ ), one of the TAM’s key beliefs, PEU, and an external variable, MI, explains as well part of the Behavioral Intention. Additionally, more than half of the information provided by MI and PEU doesn’t affect Behavioral Intention through PU. Thus, direct influence of PEU and MI on behavioral intention is found. This is not consistent with previous research, where perceived ease of use influences behavioral intention indirectly through perceived usefulness (Davis, 1989; Tarcan et al., 2010), and multimedia instruction influences behavioral intention via perceived usefulness (Liu et al., 2009). As a result of this, H2 and H6 are not true, since PEU and MI influence positively and directly Behavior Intention. On the analysis between variables, next influences have been found: PE has a significant influence on PU, and on PEU (as in Venkatesh, 2000 and Teo et al, 2011). 23 Thus, H4 y H5 are true. It has also been found a high influence from MI on PE, as in Liaw et al. (2007), which means that H7 is also true. Finally, although previous studies discovered a direct influence on PET on PEU and on PU (Taylor & Todd, 1995) it has been found low influence from PET on PEU and very low influence from PET on PU regarding the Multimedia Teaching Materials. Neither PSE influences directly Behavioral Intention, as in Albion (2001) and Liaw et al. (2007). Thus, H8, H9 and H10 are rejected. These results help us to understand instructors’ behavioral intentions towards MTM, which facilitates the creation of appropriate materials. Nevertheless, learners’ perceptions towards MTM as learning materials may also give valuable guidelines for the design of further multimedia interactive materials. Therefore, future research should explore the behavioral intention towards MTM from the learners’ point of view. It could also be relevant to apply this study to other collectives, such as the futsal and beach soccer instructors, who are also using multimedia interactive materials as a teaching tool. 7. Conclusions When developing a new teaching tool for instructors, it is necessary to assess the reasons for instructors’ acceptance of this tool and their future intentions to use it. Specifically, understanding their perceptions toward teaching technologies is a crucial issue for enhancing teaching performance. The main reason for FIFA instructors’ intention to use MTM in the future is their perceived usefulness. The user, from the perceived utility, carries out behavior that does not depend on how the other variables perform. PU is the only one that provides a significant amount of information that is not offered by others. This influence is followed by the perceived enjoyment, the perceived ease of use and the multimedia instruction quality. A meaningful direct influence from either previous experience with 24 technology or self-efficacy has not been found. A summary of the results is shown in Figure 5. In summary, MTM should be developed with these guidelines in mind: usefulness, enjoyment, ease of use and multimedia content. Fig 4. Near here The results of this research clearly confirm that instructors are willing to use MTM to aid their teaching activities as long as they perceive them as useful, enjoyable, easy to use, and whenever the material is multimedia. 25 Annex A: Questions. Var. Name 00 Age 01 Sex 02 Years of experience as an instructor Previous experience with Technology 10 What is your experience using different platforms such as Mac, PC, Blackberry or iphone? 11 What is your experience using Internet? 12 What is your experience using Power Point? 13 What is your experience using the computer as a teaching tool? 14 What is your experience using MTM ? Perceived Ease of Use 20 I find it easy to use MTM. 21 Planning and organizing MTM classes is easy. 22 I can use video in my classes in an easy and intuitive way. 23 The design of the graphic interface of the MTM materials is clear and understandable. 24 The use of MTM in classes requires little effort. 26 25 The MTM technologies allow me to achieve my objectives in a simple way. 26 Working with MTM in class is rigid and inflexible. 27 MTM technology often behaves unexpectedly. Perceived self-efficacy 30 I feel sure of myself when using MTM in teaching. 31 I am comfortable using MTM. 32 I feel nervous before teaching when using multimedia technology. Perceived enjoyment 41 I enjoy using a multimedia environment such as Power Point or Internet in teaching. 42 I enjoy using MTM as a teaching tool. 43 Using MTM as a teaching tool is satisfying. 44 Using MTM as a teaching tool is fun. 45 Using MTM as a teaching tool is positive. 46 Using MTM as a teaching tool is interesting. 47 Using MTM as a teaching tool is exciting. Perceived usefulness 50 My work as an instructor would be difficult to carry out without MTM. 51 Using MTM provides me with a large degree of control over my work. 52 MTM offers a useful tool for carrying out the tasks established in the courses. 53 Using MTM improves performance in my work. 54 Using MTM helps me save time in the teaching process. 55 Using MTM I can carry out more work than would be possible without it. 56 Using MTM cuts down on the time I dedicate to unproductive teaching activities. 57 Using MTM increases my effectiveness in work. 58 Using MTM improves the quality of the work which I carry out. 59 Using MTM makes it easier to carry out my work. Behaviour intention 60 I intend to keep using MTM for class support. 61 I intend to use MTM in my classes as much as possible. 27 62 I want to keep using MTM as opposed to stop using it. 63 I am going to talk about the positive aspects of using MTM in my classes. 64 I am going to recommend using MTM in class to other instructors. Multimedia Instruction 70 I like using video as a multimedia instruction resource. 71 I like using photography as a multimedia instruction resource. 72 I like using graphics as a multimedia instruction resource. 73 I like using animation as a multimedia instruction resource. 74 I like using the interactive self-evaluation as a multimedia instruction resource. Annex B Variables 10 10 11 1 12 13 14 20 21 22 23 24 25 0.426 0.417 0.307 0.22 0.294 0.151 0.198 0.122 0.066 0.19 1 0.659 0.744 0.592 0.594 0.465 0.495 0.473 0.157 0.484 1 0.757 0.645 0.497 0.404 0.561 0.394 0.14 0.547 1 0.796 0.652 0.488 0.622 0.468 0.148 0.547 1 0.677 0.52 0.546 0.499 0.202 0.572 1 0.803 0.656 0.686 0.388 0.752 1 0.642 0.732 0.519 0.779 1 0.609 0.365 0.736 1 0.364 0.743 1 0.411 11 12 13 14 20 21 22 23 24 25 Variables 1 26 27 30 31 32 41 42 43 44 45 46 10 0.116 0.202 0.252 0.195 -0.140 0.274 0.200 0.020 0.109 0.149 0.116 11 -0.048 0.117 0.459 0.503 0.036 0.493 0.491 0.188 0.317 0.404 0.422 12 -0.074 0.095 0.531 0.489 0.085 0.567 0.533 0.272 0.420 0.470 0.395 13 -0.041 0.086 0.548 0.527 0.206 0.558 0.617 0.289 0.412 0.506 0.536 14 0.051 0.127 0.581 0.532 0.318 0.471 0.628 0.385 0.395 0.477 0.533 20 0.173 0.204 0.650 0.731 0.348 0.591 0.785 0.411 0.503 0.602 0.679 21 0.125 0.191 0.642 0.704 0.322 0.525 0.754 0.425 0.488 0.593 0.625 22 -0.005 0.157 0.615 0.581 0.340 0.664 0.766 0.399 0.512 0.572 0.603 23 0.269 0.279 0.568 0.687 0.440 0.554 0.701 0.363 0.496 0.581 0.653 24 0.139 0.011 0.376 0.365 0.054 0.395 0.377 0.598 0.279 0.319 0.330 25 0.059 0.294 0.819 0.876 0.409 0.762 0.861 0.447 0.500 0.721 0.723 26 1 0.674 -0.013 0.066 0.352 -0.023 0.048 0.015 0.187 0.028 0.067 1 0.182 0.237 0.443 0.211 0.245 0.066 0.047 0.216 0.273 1 0.868 0.303 0.675 0.740 0.395 0.429 0.605 0.577 1 0.329 0.710 0.770 0.426 0.472 0.661 0.626 1 0.275 0.330 0.068 0.143 0.208 0.306 1 0.666 0.334 0.418 0.585 0.571 1 0.550 0.584 0.828 0.863 1 0.321 0.492 0.538 1 0.629 0.544 1 0.822 27 30 31 32 41 42 43 44 45 46 1 28 Variables 60 61 62 63 64 70 71 72 73 74 10 0.171 0.129 0.220 0.273 0.088 0.119 0.249 0.206 0.159 0.067 11 0.438 0.406 0.184 0.384 0.249 0.415 0.170 0.084 0.192 0.211 12 0.323 0.301 0.140 0.253 0.130 0.349 0.193 0.091 0.243 0.171 13 0.264 0.318 0.049 0.200 0.124 0.398 0.270 0.156 0.337 0.227 14 0.298 0.293 0.038 0.171 0.116 0.365 0.278 0.223 0.369 0.278 20 0.490 0.443 0.197 0.362 0.246 0.479 0.281 0.253 0.320 0.259 21 0.491 0.444 0.221 0.365 0.315 0.444 0.137 0.143 0.289 0.207 22 0.506 0.510 0.237 0.258 0.372 0.552 0.205 0.274 0.487 0.405 23 0.472 0.444 0.205 0.335 0.353 0.501 0.174 0.193 0.317 0.361 24 0.320 0.252 0.381 0.338 0.334 0.294 0.090 0.166 0.257 0.200 25 0.581 0.586 0.278 0.465 0.416 0.437 0.166 0.252 0.419 0.411 26 0.087 -0.008 0.074 0.060 -0.012 0.089 -0.095 -0.075 -0.098 -0.136 27 0.181 0.255 0.183 0.248 0.258 0.203 -0.087 0.017 0.067 0.039 30 0.519 0.484 0.241 0.443 0.369 0.327 0.318 0.294 0.379 0.305 31 0.583 0.535 0.265 0.474 0.368 0.397 0.195 0.220 0.321 0.355 32 0.098 0.142 0.077 0.141 0.128 0.108 0.056 0.136 0.185 0.195 41 0.455 0.403 0.274 0.415 0.386 0.407 0.252 0.340 0.525 0.438 42 0.628 0.644 0.245 0.414 0.385 0.583 0.246 0.282 0.485 0.409 43 0.386 0.479 0.356 0.259 0.291 0.396 0.174 0.215 0.350 0.357 44 0.572 0.330 0.088 0.211 0.146 0.455 0.216 0.173 0.311 Variables 45 10 46 470.648 0.606 0.073 50 0.624 0.685 0.100 51 0.233 0.287 0.248 52 0.441 0.454 0.287 53 0.414 0.551 -0.059 54 0.604 0.693 -0.036 55 0.326 0.344 0.145 56 0.306 0.351 -0.141 11 47 0.575 0.269 0.488 0.051 0.128 0.288 0.275 0.363 0.349 0.134 0.564 0.241 0.323 0.246 12 50 13 51 0.224 0.144 0.296 0.437 0.009 0.312 -0.063 0.429 0.262 0.378 0.194 0.391 0.296 0.277 0.265 0.553 0.234 0.225 0.191 0.380 0.213 0.104 0.238 0.181 14 52 20 53 0.310 0.644 0.524 0.491 -0.033 0.656 0.064 0.579 0.163 0.636 0.326 0.318 0.269 0.750 0.398 0.439 0.189 0.729 0.273 0.541 0.472 0.451 0.423 0.481 0.515 0.280 0.235 0.375 0.488 0.602 0.111 0.479 0.070 0.479 0.239 0.289 0.537 0.403 0.228 0.370 0.354 0.516 0.308 0.014 0.249 0.183 0.4805 0.448 0.416 0.394 0.471 0.600 0.388 0.271 0.366 0.396 0.568 0.515 0.105 0.508 0.378 0.691 0.486 21 57 0.493 0.219 58 0.392 59 0.525 0.017 0.529 0.396 -0.093 0.421 0.010 0.546 -0.016 0.416 0.189 0.198 0.066 0.249 0.152 0.012 0.064 0.025 0.179 0.172 0.060 0.286 0.333 0.430 0.251 0.428 0.275 0.189 0.236 0.449 0.405 0.415 0.204 0.267 0.400 0.285 0.015 0.426 0.145 0.307 0.182 0.577 0.329 0.467 0.433 0.456 0.511 0.441 0.207 0.538 0.418 0.354 0.619 0.481 0.368 0.408 0.567 0.564 0.531 -0.047 0.581 0.156 0.639 0.456 0.677 0.444 0.363 0.427 0.576 0.238 0.475 0.405 0.573 0.503 -0.028 0.443 0.076 0.583 0.492 0.412 0.181 0.412 0.221 0.408 0.119 0.278 0.318 0.491 0.275 0.057 0.271 0.234 0.201 0.490 0.258 0.134 0.301 0.261 0.216 0.279 0.278 0.311 0.269 0.256 -0.093 0.275 -0.074 0.219 0.241 0.330 0.304 0.416 0.351 0.435 0.258 0.272 0.483 0.487 0.417 -0.054 0.362 0.143 0.309 0.443 0.572 0.356 0.501 0.351 0.582 0.259 0.297 0.502 0.665 0.425 0.018 0.422 0.236 0.379 0.588 0.471 0.694 0.442 0.625 0.230 0.543 0.518 0.237 0.201 0.257 0.466 0.041 0.215 0.276 0.258 0.194 -0.006 0.439 0.413 0.228 0.154 0.524 0.606 0.236 0.258 0.383 0.180 0.181 0.219 27 59 30 60 0.382 0.165 0.469 -0.045 0.546 0.064 0.218 0.229 0.596 0.091 0.678 -0.124 0.515 -0.002 1 0.048 0.814 31 61 0.468 0.118 1 0.490 0.538 32 62 0.174 -0.171 0.152 0.668 0.474 1 0.255 0.685 41 63 0.381 0.063 0.532 0.576 10.418 0.735 0.362 0.410 0.232 0.404 0.313 0.240 0.293 0.421 0.306 0.496 0.320 42 64 0.632 0.098 0.433 0.540 0.547 0.533 0.293 0.233 0.441 0.520 0.448 0.695 0.517 0.433 43 70 0.368 0.353 0.187 0.295 0.308 10.581 0.571 0.363 71 0.704 -0.120 0.290 0.340 0.325 0.347 0.127 0.373 10.287 0.744 0.328 0.566 0.269 0.574 0.446 0.567 0.491 0.363 0.266 44 10.343 0.391 0.245 45 72 0.676 0.137 0.484 0.550 0.658 0.596 0.476 0.247 0.733 0.147 0.423 0.626 0.616 0.616 0.640 0.301 0.749 0.579 0.801 1 0.651 0.573 73 0.506 1 0.690 0.685 1 0.061 0.311 0.442 0.492 0.505 0.403 0.316 0.439 0.624 1 0.458 0.1460 0.338 0.375 0.257 0.047 0.216 0.175 0.440 1 0.282 1 0.665 0.644 0.628 0.461 0.288 0.411 0.574 0.548 1 0.586 0.444 0.645 0.363 0.544 0.636 0.575 1 0.797 0.456 0.357 0.579 0.714 0.830 1 0.611 0.386 0.534 0.640 0.751 1 0.404 0.663 0.593 0.488 1 0.291 0.317 0.394 1 0.739 0.578 1 0.740 22 23 24 25 26 46 47 50 54 55 56 57 58 74 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 0.270 0.342 0.405 0.466 -0.090 0.131 0.420 0.159 0.258 0.570 1 7. References Agarwal, R., & Karahanna, E. (2000). Time Flies When You're Having Fun: Cognitive Absorption and Beliefs about Information Technology Usage. MIS Quarterly, 24(4), 665-694. 29 Albion, P. R. (2001). Some Factors in the Development of Self-Efficacy Beliefs for Computer Use Among Teacher Education Students. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 9 (3),321-347. Armenteros, M., & Curca, D. (2008). Use of educational hypermedia for learning Laws of Game.FIFA Multimedia Teaching Materials. Paper presented at the XII World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications. Vienna, Austria. Armenteros, M., Benítez, A. J., & Sillero, M. (2009). Interactive video test used for the training of football referees. Paper presented at the IADIS Multiconference on computer science and information systems. Algarve, Portugal. Armenteros, M., Benítez, A. J., & Curca, D. G. (2010). El Trivia interactivo como recurso educativo para el aprendizaje de las reglas de juego del fúltbol. EdutecE.Revista Electrónica de Tecnología Educativa, 30. Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191 - 215. Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action. New Jersey: Englewood Cliffs. 30 Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2011). E-Learning and the Science of Instruction: Proven Guidelines for Consumers and Designers of Multimedia Learning. San Francisco: Pfeiffer. Compeau, D. R., & Higgins, C. A. (1995). Computer Self-Efficacy: Development of a Measure and Initial Test. MIS Quarterly, 19(2), 189-211. Chesney, T. (2006). An acceptance model for useful and fun information systems Human Technology, 2(2), 225 - 235. Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3). Davis, F. D. (1993). User acceptance of information technology : system characteristics, user perceptions and behavioral impacts.Internationl Journal of Man Machine Studies, 38(3), 475 - 487. Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Management Science, 35(8). Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1992). Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation to Use Computers in the Workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22(14), 1111-1132. 31 Davis, S., & Wiedenbeck, S. (2001). The mediating effects of intrinsic motivation, ease of use and usefulness perceptions on performance in first-time and subsequent computer users. Interacting with Computers, 13(5), 549-580. Deniz, M. (2010). Changing Consumption Behavior of Net Generation and the Adoption of Streaming Music Services. Extending the Technology Acceptance Model to Account for Streaming Music Services. Economics and Management of Entertainment & Arts, Jönköping University, Jönköping. Fédération Internationale de Football Association (2010). FIFA course catalogue. Retrieved June 4, 2012, from http://www.fifa.com/mm/document/affederation/courses/01/06/22/80/fifacourse catalogue_2010.pdf Fetscherin, M., & Lattemann, C. (2008). User acceptance of virtual worlds.Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 9(3). Horton, W. (2006). E-Learning by Design. San Francisco: Pfeiffer. Igbaria, M., Schiffman, S. J., & Wieckowski, T. J. (1994). The respective roles of perceived usefulness and perceived fun in the acceptance of microcomputer technology. Behaviour & Information Technology 13(6). 32 Lee, M. K. O., Cheung, C. M. K., & Chen, Z. (2005). Acceptance of Internet-based learning medium: the role of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Information & Management, 42(8), 1095-1104. Liaw, S.-S., Huang, H.-M., & Chen, G.-D. (2007). Surveying instructor and learner attitudes toward e-learning. Computers & Education, 49(4), 1066-1080. Liu, S.-H., Liao, H.-L., & Pratt, J. A. (2009). Impact of media richness and flow on elearning technology acceptance. Computers & Education, 52(3), 599-607. Mayer, R. (2005). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning New York: Cambridge University Press. Mathieson, K. (1991). Predicting user intentions: comparing the technology acceptance model with the theory of planned behavior. Information Systems Research, 2(3),173–191. Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Consumer Acceptance of Electronic Commerce: Integrating Trust and Risk with the Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Electron. Commerce, 7(3), 101-134. Saadé, R. G., Nebebe, F., & Tan, W. (2007). Viability of the “Technology Acceptance Model” in Multimedia Learning Environments: A Comparative Study. Interdisciplinary Journal of Knowledge and Learning Objects, 3, 175-184. 33 Sánchez, R. A., & Hueros, A. D. (2010).Motivational factors that influence the acceptance of Moodle using TAM. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 1632– 1640. Tarcan, E., Varol, E. S., & Toker, B. (2010). A Study On The Acceptance Of Information Technologies From The Perspectives Of The Academicians In Turkey. Ege Academic Review, 10(3). Taylor, S., & Todd, P. (1995). Assessing IT Usage: The Role of Prior Experience. MIS Quarterly, 19(4), 561-570. Teo, T., Lim, V., & Lai, R. (1999). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in Internet usage. Omega, 27, 25 - 37. Teo, T., Lee, C. B., & Chai, C. S. (2008). Understanding pre-service teachers' computer attitudes: applying and extending the technology acceptance model. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 24(2), 128-143. Teo, T., & Noyes, J. (2011). An assessment of the influence of perceived enjoyment and attitude on the intention to use technology among pre-service teachers: A structural equation modeling approach. Computers & Education, 57(2), 16451653. Van der Heijden, H. (2004). User Acceptance of Hedonic Information Systems. MIS Quarterly, 28(4), 695-704. 34 Venkatesh, V. (2000). Determinants of Perceived Ease of Use: Integrating Control, Intrinsic Motivation, and Emotion into the Technology Acceptance Model. Information Systems Research, 11(4), 342-365. Venkatesh, V., Speier, C., & Morris, M. G. (2002). User Acceptance Enablers in Individual Decision Making About Technology: Toward an Integrated Model. Decision Sciences, 33(2), 297-316. Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425478. Yoo, S. J., Han, S.-h., & Huang, W. (2012). The roles of intrinsic motivators and extrinsic motivators in promoting e-learning in the workplace: A case from South Korea. Computers in Human Behavior, 2012. 35