SOAS – University of London Academic Development Directorate

advertisement

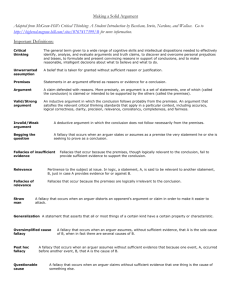

SOAS – University of London Academic Development Directorate Critical Thinking Workshop Introduction Study of the relationship between dietary practice and health A survey was conducted by Oxford University on the correlation between the occurrence of the 20 most popular diseases and dietary practice. The study looked at comparable samples of vegetarians and non-vegetarians, and the occurrence of the said diseases within those groups. The survey showed a significantly greater correlation between those diseases and vegetarian group than with the non-vegetarian group. What can one conclude from these results? What questions should we ask about the results and research? The workshop looks at: • Perception • Reasoning • Credibility • Fallacy Aim of the Workshop To lay the groundwork for clear thinking and provide opportunities to: • Develop a systematic and critical approach to reading/research • Acquire the skills and tools central to critical analysis • Express thoughts and findings clearly and unambiguously Perception • Six blind men in a dark room • Wall • Spear • Snake • Tree • Fan • Rope BLUE Denotation Connotation OR Mehmet Izbudak [mi29@soas.ac.uk] ATD SOAS a. Killing b. Slaughter c. Murder d. Massacre e. Genocide The Flat Earth Society • Describe the type of person who founded the organisation. • When do you think it was founded? • Why do you think it was founded? • Does it still have a membership? 3 arguments FOR 3 arguments AGAINST It’s silly to retire at the age of 60 or 65. Why don’t we start with retirement immediately after school and higher education and go on to work from the age of 45 or 50. Wouldn’t that make more sense? 3 arguments FOR 3 arguments AGAINST Democracy, as it is, will never work because anyone and everyone over the age of 18, whatever their intelligence, can vote at the general elections. Most people don’t know what is going on. Wouldn’t it make more sense if only the educated could vote? For example: only people with degrees. Method of Doubt Cogito ergo sum • René Descartes [1596-1650] • “to demolish everything completely and start again right from the foundations” Unlike “the skeptics, who doubt only for the sake of doubting,” Descartes aims “to reach certainty— to cast aside the loose earth and sand so as to come upon rock or clay” Descartes is sitting in a bar, having a drink. The barman asks him if he would like another. "I think not," he says, and vanishes. What is Critical? The word critical is derived from a Greek root word (krinein) meaning to separate or choose. What is thinking? • Ritual thinking • Random Thinking • Appreciative Thinking • Critical Thinking Reasoning One Mehmet Izbudak [mi29@soas.ac.uk] ATD SOAS • Take 20 marbles at random from a large bag of marbles. • Every one of them turns out to be white. • The observation is: every marble taken out was white. • The explanatory hypothesis is that all the marbles in the bag were white. • Further sampling might be required to test the hypothesis This is INDUCTION Specific → General 1. Start with specific results and try to guess the general rule[s]. 2. Hypotheses can only be disproved, never proved! 3. If a hypothesis withstands repeated trials by several independent researchers, then conviction grows in the hypothesis. 4. All hypotheses are tentative. Reasoning Two o There is a large bag of marbles. o All of the marbles in the bag are white. o We have a random sample of 20 marbles taken from the bag. o I can therefore deduce that all the marbles in the sample are white. • OR o There is a large bag of marbles. o All of the marbles in the bag are white. o We have a random sample of 20 marbles of mixed colours. o I can therefore deduce that the sample was not taken from the bag of white marbles. This is DEDUCTION Deductive syllogism All humans are mortal Socrates is human Socrates is mortal Deductive syllogism 2 All humans are a variety of sheep Socrates is human Socrates is a sheep • OR My sister-in-law is superficial. My sister-in-law is a Conservative. Therefore, Conservatives are superficial! • OR My sister-in-law is superficial. Mehmet Izbudak [mi29@soas.ac.uk] ATD SOAS My sister-in-law is a Conservative. Therefore, some Conservatives are superficial! OR My sister-in-law is superficial. My sister-in-law is a Conservative. Therefore, at least one Conservative is superficial! A Simple System for Critical Analysis So here is a six-step plan offering a simple and useful way of breaking the process into stages • 1. Locate the conclusion Many arguments are constructed after their conclusions have been determined. Starting with the conclusion may not only reveal special assumptions, but the actual motive behind the argument. • 2. Clarify the language: Ambiguities make logical argument impossible. Identify the key definitions upon which the argument rests and recast any dubious language. • 3. Eliminate the excess Remove anything which may distract from the actual argument; eliminate any prejudicial language in favour of a neutral wording. Remove clutter, such as universally-accepted definitions or assumptions (be careful of these). • 4. Identify assumptions Many statements clearly depend on unstated propositions. Locate such dependant statements and make their foundations explicit. • 5. Classify statements Statements can be either statements of fact or statements of opinion; distinguish between the two. • 6. Isolate the structure of the argument Determine which statements serve as premises, and re-state them in logical form. You may find it helpful to symbolize them using standard logical notation. However it is accomplished, you must evaluate the formal structure of the argument to determine whether it is complete and valid. Apart from reasoning… How do we deal with the information upon which our argument is based? How do we assess this information? Criteria of Credibility • Much of the information that comes to us is second-hand • How do we then decide which sources of information to trust? • If the sources of information contradict • When a number of sources convey difference things, how do we decide which one[s] to believe? RAVEN R = Reputation A = Ability to see V = Vested interest E = ExpertiseN = Neutrality • Reputation - whether the source’s history or status suggests reliability or unreliability. Mehmet Izbudak [mi29@soas.ac.uk] ATD SOAS • Ability to See - whether the source in a position to know what they’re talking about. • Vested Interest - whether the source of information has anything personally at stake. • Expertise - specialized knowledge • Neutrality - whether someone is predisposed to support a particular point of view for reasons other than vested interest. Fallacies Definition 1 misconception resulting from incorrect reasoning wordnet.princeton.edu/perl/webwn Definition 2 a mistaken inference; faulty reasoning; a seemingly reasonable argument which is actually unsound or flawed. www.tmsdebate.org/main/forensics/glossary.htm Definition 3 A fallacy is an argument which seems to be correct but which contains at least one error and, as a consequence, produces a final statement which is clearly wrong. Though it is clear that the result is wrong, the error in the argument is usually (and ought to be) difficult to find.ddi.cs.unipotsdam.de/Lehre/TuringLectures/MathNotions.htm 1. Hasty generalization • "My roommate said her economics class was hard, and the one I'm in is hard, too. All economics classes must be hard!" • Making assumptions about a whole group or range of cases based on a sample that is inadequate Stereotypes about people ("librarians are shy and smart," "wealthy people are snobs," etc.) are a common example of the principle underlying hasty generalization. • Ask yourself what kind of "sample" you're using: Are you relying on the opinions or experiences of just a few people, or your own experience in just a few situations? 2. Missing the point • "The seriousness of a punishment should match the seriousness of the crime. Right now, the punishment for drunk driving may simply be a fine. But drunk driving is a very serious crime that can kill innocent people. So the death penalty should be the punishment for drunk driving." • The premises of an argument do support a particular conclusion—but not the conclusion that the arguer actually draws. • Separate your premises from your conclusion. Looking at the premises, ask yourself what conclusion an objective person would reach after reading them. 3. Post hoc (false cause) • "President Jones raised taxes, and then the rate of violent crime went up. Jones is responsible for the rise in crime." • Assuming that because B comes after A, A caused B. Correlation isn't the same thing as causation. • If you say that A causes B, you should have something more to say about how A caused B than just that A came first and B came later. 4. Slippery slope Mehmet Izbudak [mi29@soas.ac.uk] ATD SOAS • "Animal experimentation reduces our respect for life. If we don't respect life, we are likely to be more and more tolerant of violent acts like war and murder. Soon our society will become a battlefield in which everyone constantly fears for their lives. It will be the end of civilization. To prevent this terrible consequence, we should make animal experimentation illegal right now." • The arguer claims that a sort of chain reaction, usually ending in some dire consequence, will take place, but there's really not enough evidence for that assumption. • Check your argument for chains of consequences, where you say "if A, then B, and if B, then C," and so forth. Make sure these chains are reasonable. 5. Weak analogy • "Guns are like hammers—they're both tools with metal parts that could be used to kill someone. And yet it would be ridiculous to restrict the purchase of hammers—so restrictions on purchasing guns are equally ridiculous." • Many arguments rely on an analogy between two or more objects, ideas, or situations. If the two things that are being compared aren't really alike in the relevant respects, the analogy is a weak one, and the argument that relies on it commits the fallacy of weak analogy. • Identify what properties are important to the claim you're making, and see whether the two things you're comparing both share those properties. 6. Appeal to authority • "We should abolish the death penalty. Many respected people, such as the Dalai Lama, have publicly stated their opposition to it." • There are two easy ways to avoid committing appeal to authority: First, make sure that the authorities you cite are experts on the subject you're discussing. Second, rather than just saying "Dr. Authority believes x, so we should believe it, too," try to explain the reasoning or evidence that the authority used to arrive at his or her opinion. That way, your readers have more to go on than a person's reputation. It also helps to choose authorities who are perceived as fairly neutral or reasonable, rather than people who will be perceived as biased. 7. Ad populum • "Gay marriages are just immoral. 70% of the population think so!" • The Latin name of this fallacy means "to the people." There are several versions of the ad populum fallacy, but what they all have in common is that in them, the arguer takes advantage of the desire most people have to be liked and to fit in with others and uses that desire to try to get the audience to accept his or her argument. • Popular opinion is not always the right one! 8. Ad hominem • “Jane Dworkin has written several books arguing that pornography harms women. But Dworkin is an ugly, bitter person, so you shouldn't listen to her." • Like the appeal to authority and ad populum fallacies, the ad hominem ("against the person") fallacies focus our attention on people rather than on arguments or evidence. In an ad hominem argument, the arguer attacks his or her opponent instead of the opponent's argument. • Be sure to stay focused on your opponents' reasoning, rather than on their personal character. 9. Appeal to ignorance Mehmet Izbudak [mi29@soas.ac.uk] ATD SOAS • "People have been trying for centuries to prove that God exists. But no one has yet been able to prove it. Therefore, God does not exist." OR : "People have been trying for years to prove that God does not exist. But no one has yet been able to prove it. Therefore, God exists." • The arguer basically says, "Look, there's no conclusive evidence on the issue at hand. Therefore, you should accept my conclusion on this issue." • Look closely at arguments where you point out a lack of evidence and then draw a conclusion from that lack of evidence. 10. Straw man • Feminists want to ban all pornography and punish everyone who reads it! But such harsh measures are surely inappropriate, so the feminists are wrong: Porn and its readers should be left in peace." • In the straw man fallacy, the arguer sets up a wimpy version of the opponent's position and tries to score points by knocking it down. But just as being able to knock down a straw man, or a scarecrow, isn't very impressive, defeating a watered-down version of your opponents' argument isn't very impressive either. • Be fair to your opponents. State their arguments as strongly, accurately, and sympathetically as possible. If you can knock down even the best version of an opponent's argument, then you've really accomplished something. Most academic writing tasks requires one to present an argument i.e. to present reasons for a particular claim or interpretation that is being put forward. Arguments can be reinforced by: 1. using good premises 2. providing good support for the conclusion 3. addressing the most important or relevant aspects of the issue 4. not making claims that are so strong or sweeping that one can't really support them • How to identify fallacies in your own writing? Play Devil’s Advocate. Pretend to disagree with the conclusion you are defending. List your main points and list the evidence you have for each point. Identify the types of fallacies you're especially prone to. Be aware that broad claims need more proof than narrow ones. Mehmet Izbudak [mi29@soas.ac.uk] ATD SOAS