The Endangered Species Act_Oct. 2011

advertisement

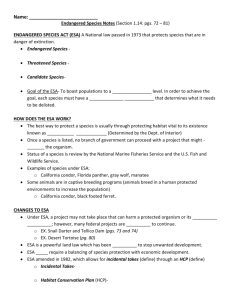

The Endangered Species Act by DeAnna Worthington The Endangered Species Act (ESA) was passed by Congress and signed into law in 1973 by President Richard Nixon. The goal of the ESA, then and now, is to preserve endangered species and to conserve the ecosystems in which these species live.i The ESA has been described as both, “the world’s most potent single piece of environmental legislation…,” iiand as, “an utter failure.” iii The purpose of this paper will be to discuss various aspects of the ESA. In doing so, it will: 1) review the reasons the ESA was enacted, 2) describe the features of the 1973 Act and some of its subsequent amendments, 3) discuss the criticisms raised against and support given for the ESA, and 4) conclude that the ESA is imperative to the continuing existence and vitality of plants, animals, fish, and human species. A primary reason for the ESA was to combat the population decline of plant and animal species in risk of extinction. Various factors brought about this decline. Hunting and sporting by early settlers of America was one cause of the decline. Another cause was the destruction of animal habitation. Farming techniques, such as the use of pesticides and herbicides, contributed to habitat destruction. Commercial development also hindered the survival of many species due to mining, housing developments and logging. The development of America’s infrastructure, including highways and railways, further contributed to species decline.iv Prior to the enactment of the ESA, certain animals were on the verge of extinction more than others. One example was the American buffalo. “There were probably 25 to 30 million bison in North America when the Europeans arrived...”v Native Americans used almost every part of the buffalo and because of this respect for the animal, there was merely a minor dent in the decline of the buffalo population. By contrast, early European settlers found the hunting of buffalo to be a sport and used it for profit.vi “By 1870, the great herds of buffalo had vanished. What were left were huge heaps of bones and rotting flesh. A few stragglers remained, but for all practical purposes, the buffalo was gone.”vii Animals were killed because of various reasons. Ranchers and herders killed the grizzly bear and gray wolf because of their danger to humans and to their flocks and herds. “In 1905, cattlemen forced the state of Montana to pass a law requiring the state veterinarian to infect captive wolves and then release them to spread disease among the wolf population.”viii By contrast, the bald eagle was not killed due to its potential harm to humans. Rather, it became nearly extinct because it fed on small animals and insects infected by pesticides used in farming to control insects.ix Some animals neared extinction because of the extinction of animals they preyed on. For example, the black- footed ferret solely survived on the prairie dog for food, thus the extinction of the prairie dog threatened the extinction of the ferret.x Early efforts of preservation of nature protection leading up to the ESA include the creation of national parks in the nineteenth century, including Yosemite and Yellowstone National Parks. In addition, the growing popularity of natural history museums created an awareness of biological diversity.xi In terms of legislation, The Lacey Act of 1900 prohibited the interstate commerce of animals which were illegally captured according to state laws.xii “The Lacey Act was revolutionary, essentially the first endangered species law. It enhanced existing legislation by making the possession, transport, or sale of wildlife a separate offense from the initial act of poaching.”xiii As a result of the above issues, the ESA was passed by Congress and signed into law in 1973. The purpose of the ESA is to “provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved.”xiv To “take”, remove, hunt or destruct an endangered species habitat is prohibited in the Act. “Cutting trees, clearing land, or diverting a river or stream”xv are acts identified by the ESA as potentially being in violation of the law.xvi A section of the Act addresses recovery plans for a species that has been listed. The ESA also addresses how a species is to be identified and listed as endangered. Upon being added to the list, a species is either listed as threatened or endangered. A species that is likely to become endangered would be listed as threatened, whereas a species in more critical need or that is likely to become extinct would be listed as endangered.xvii The ESA authorizes the government to purchase land and give financial assistance in order to protect the habitat of listed species.xviii The ESA also includes the protection of plants. This helps to insure not only animals are protected but also plants that they rely on. The Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) is designated to oversee the ESA and this agency is provided with a large budget to effectuate its intent.xix Under the Act, the government is also obliged to protect endangered species, thus affecting government projects such as highways, dams and bridges.xx Since its enactment, there have been amendments to the ESA. One amendment adds economic considerations when determining what constitutes critical habitat.xxi The Act states, “The Secretary shall designate critical habitat, and make revisions thereto, under subsection (a)(3) on the basis of the best scientific data available and after taking into consideration the economic impact, and any other relevant impact, of specifying any particular area as critical habitat..”xxii Another amendment allows property owners to develop a portion of their land if they will, in exchange, leave other portions of their lands protected. A compromise such as this is called Habitat Conservation Plans (HCP).xxiii Supporters of the ESA have promoted its effectiveness. One reason the ESA has been viewed as a success is that it is working, in other words, recovery has been achieved for many species. One example of a species that has been saved, in part, by the ESA is the bald eagle, the nation’s symbol. At one time, the number of eagles had dwindled down to less than 500 pairs. After implementation of the act, there is estimated to be nearly 4,000 pairs.xxiv Other animals which are considered recovered are “the whooping cranes, California sea otters, peregrine falcons, black-footed ferrets, Kirtland’s warblers, brown pelicans, red wolves, Aleutian Canada geese and Peter’s Mountain mallow wildflowers.”xxv In addition to species recovery, other benefits have resulted in the passage of the ESA. For instance, supporters of the act have emphasized the economic value brought about by the ESA. Jobs have been created in industries such as the sustainable extraction of species and ecotourism.xxvi In addition, medical and pharmaceutical fields have benefited from the preservation of plants and animals as it is estimated that “as many as 40 percent of prescription medicines today are derived from wild plants and animals.”xxvii Consequently, with the availability of these plants and animals for use as medications, human health has improved and lives have been saved. Others have raised criticisms against the ESA. One of the biggest criticisms is that is violates private property rights, or personal freedoms, as guaranteed by the Bill of Rights of the US Constitution. Private property owners must abide by regulations in the ESA which include, “clearing dead brush, grazing cattle, putting in erosion barriers, home improvements or anything else that might harm, capture, trap, collect, pursue, harass, wound or kill one federally protected beetle, snail, snake or bird.”xxviii Fines and jail time are possible results for those caught violating the regulations.xxix Another criticism against the ESA is that the data provided to add or remove a species to the endangered list is not scientifically accurate or reliable. The information is based off of the “best available data.”xxx However, since scientific data is not required by the ESA, many believe the recovery of a species may be the result of an initial undercounting when the species was initially added to the list.xxxi Other critics of the ESA point to the enormous cost associated with listing and protecting endangered species. People often overlook that protection costs are in the billions. In addition, jobs are lost when they conflict with the executed protection plans. For instance, if the plans to save the spotted owl proceed and, it will cost more than $700 million annually to pay for unemployment benefits. xxxii Despite the criticisms raised, we, as a nation are better off because of the ESA. It is our moral obligation to protect species because we are all part of a shared ecosystem. If a species becomes extinct because of human causes, the result is an imbalance in the natural order.xxxiii “The biological integrity of the world and its spiritual integrity are stunningly intertwined…”xxxiv The Native Americans do not separate species, land and humans into separate categories, but see them as belonging to an interconnected whole .xxxv “What is man without the beasts? If all the beasts were gone, man would die from a great loneliness of spirit. For whatever happens to the beasts, soon happens to man. All things are connected… “xxxviA is a vital importance to all of us because in protecting plant, animal and fish species, we are, in turn, protecting the human race for generations to come. i Endangered Species Act of 1973 SEC. 2. [16 U.S.C. 1531] http://epw.senate.gov/esa73.pdf ii Douglas Chadwick, quoted in Bonnie B. Burgess, Fate of the Wild: The Endangered Species Act And The Future of Biodiversity,The University of Georgia Press, 2001 at 20. iii Robert E. Gordon, The Endangered Species Act Is a Failure, in Endangered Species: Opposing Viewpoints, Greenhaven Press, 1996 at 67. iv A list of contributing factors for the decline of species can be found at David Goodnough, Endangered Animals of North America: A Hot Issue, Enslow Publishers (2001) at 25-27. v Joe Roman, Listed: Dispatches From America’s Endangered Species Act, Harvard University Press (2011), at 55. vi Goodnough at 11-14. vii Goodnough at 14. viii Goodnough at 41. Goodnough at 8. x Goodnough at 44. xi Roman at 54 xiixii Roman at 58 xiii Roman at 58 xiv Endangered Species Act of 1973 SEC. 2. [16 U.S.C. 1531] found at http://epw.senate.gov/esa73.pdf ix xv Roman at 53. Roman at 53. xvii Roman at 53, 54. xviii Roman at 53. xix Goodnough at 37, 38. xx Goodnough at 37, 38. xxi Endangered Species Act of 1973 S SEC. 4. [16 U.S.C. 1533] found at http://epw.senate.gov/esa73.pdf xvi xxii Endangered Species Act of 1973 S SEC. 4. [16 U.S.C. 1533] found at http://epw.senate.gov/esa73.pdf xxiiixxiii Goodnough at 39. xxiv Michael J Bean, The Endangered Species Act Is Effective, in Endangered Species: Opposing Viewpoints, Greenhaven Press, 1996 at 75, 76. xxv Bean at 75, 76. Burgess at 132. xxvii Burgess at 55. xxviii Gordon at 71. xxix Gordon at 71. xxx Gordon at 68. xxxi Gordon at 67, 68. xxvi xxxii Gordon at 71. Burgess at 53. xxxiv Burgess at 53. xxxv Burgess at 54. xxxvi Burgess at 54. xxxiiixxxiii