SAA 2014- Multilingual Finding Aids ( DOCX )

advertisement

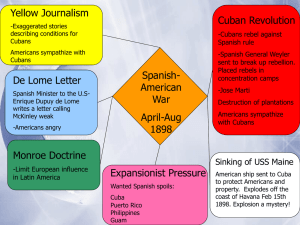

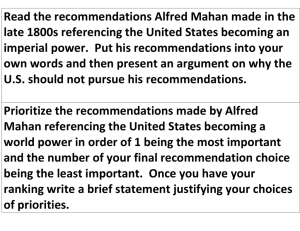

Margarita Vargas-Betancourt Caribbean Basin Librarian University of Florida July 2014 SAA 2014 Conference paper SESSION 307 Many Languages, One Archives: Creating Multilingual Finding Aids and Digital Collections [SLIDE 1] “Creating Multilingual Finding Aids: Cuban Collections at the University of Florida” [SLIDE 2] At the University of Florida (UF), the collection of Latin American material especially that related to the Caribbean began in the 1930s with the creation of the Institute for InterAmerican Affairs by UF’s president John J. Tigert. Tigert believed that the University of Florida had a special role because of its immediacy to the Caribbean.1 In 1948, U.S. librarians developed the Farmington Plan, a collaborative agreement among select U.S. libraries in which each would be asked to specialize in a region. Recognizing the strength of UF’s Latin American Collection, in 1951 the Farmington Plan assigned UF as the repository for Caribbean material.2 Since then, the Latin American Collection has worked to fulfill this mission. The acquisition of manuscripts has been part of such undertaking. The result is a significant number of multilingual manuscript collections. The purpose of this paper is to discuss one case study: Cuban collections at UF. [SLIDE 3] 1 http://www.latam.ufl.edu/history. 2 Ralph D. Wagner, A History of the Farmington Plan (Lanhuam: Scarecrow Press, 2002), 84. 1 The Braga Brothers Collection is the most extensive Cuban collection at UF (375 linear feet).3 Since it documents one hundred years of the history of sugar production in Cuba (18601960s), it is perhaps the one that represents Cuban history most comprehensively at the Libraries. The collection exemplifies the business partnerships that took place between American and Latin American companies in the 19th and 20th centuries. In this way, it provides a glance of the relationships between the two regions, and, thus, helps to understand the current connections between the U.S., Latin America, and Latin American immigrants. The collection was donated to UF in 1981. Although its contents are in English and Spanish, the finding aid is written in English only. The lack of a Spanish finding aid prevents access to patrons who only speak Spanish. As part of the George A. Smathers Libraries, the Latin American and Caribbean Collection at UF has the mission to support the needs of the faculty, students, and the rest of the University of Florida community.4 The diversity that now characterizes such patrons originates a continuous demand for multilingual points of access to manuscript collections. Furthermore, collaboration with Latin American partners and more Latin American visitors to our collections broaden the need for bilingual finding aids. The impact of providing multilingual finding aids is even experienced in the negotiation with donors over gifts to UF’s Libraries, for instance, the donation of Cuban collections related to the Cuban Revolution. Lillian Guerra, Professor of Cuban and Caribbean History at UF, has collaborated with the Libraries in the negotiation of the donation of several Cuban collections, such as the Manuel 3 http://web.uflib.ufl.edu/spec/manuscript/braga/braga.htm 4 http://www.uflib.ufl.edu/search.html?cx=002991405718492227978%3Aa3xnpi_fuq&sa=Search&cof=FORID%3A11&q=mission 2 Ray Oral History Collection, the Rafael Martínez Pupo Papers Relating to Comandos Mambises, the Carlos González Blanco Collection, and the Reina Peñate de Tito Collection. Ray played an important role in the Cuban Revolution and in the counterrevolutionary movements that followed it. Guerra interviewed Ray and his wife Aurora Chacón in February 2009. The significance of the interview to Ray is that it covers his activity during the 26th of July Movement as well as Ray’s alienation from Fidel Castro when the latter asked Ray to support the execution of Huber Matos in 1959.5 In addition, the interview to Chacón highlights the experience that women, especially wives of activists, had during the revolution and the counterrevolution movements.6 The collection that Guerra donated to the University of Florida includes not only the filmed interviews but also their transcription. This collection is entirely in Spanish. For this reason, after processing the collection and creating a finding aid in English, Margarita Vargas-Betancourt, the Caribbean Basin Librarian at UF, proceeded to create a finding aid in Spanish.7 [SLIDE 4] In 2011, Guerra established contact with Alejandro de la Cruz and with Frida Masdeu and started negotiating the donation of two collections. De la Cruz donated his grandfather’s papers: the Rafael Martínez Pupo Papers Relating to Comandos Mambises. As stated in the finding aid for this collection, Martínez Pupo “was a successful business man in Cuba who lost 5 Huber Matos was a Protestant leader that became an important figure in the revolution against Batista. Alan West-Durán, ed., Cuba Volume 1 (Farmington Hills: GALE CENGAGE Learning, 2012), 313. 6 http://web.uflib.ufl.edu/spec/manuscript/guides/ray.htm 7 http://www.library.ufl.edu/spec/manuscript/guides/ray_es.htm 3 all of his enterprises and belongings when Fidel Castro nationalized private property in 1959.”8 After going into exile, Martínez Pupo organized a sabotage group, the Comandos Mambises, whose target was Cuban infrastructure. The collection documents the activities of this group. After Guerra established contact with De la Cruz, Vargas-Betancourt followed up with the donation. In both cases, the communication took place in Spanish. The Latin American identity of Guerra (Cuban) and of Vargas-Betancourt (Mexican) seems to have facilitated the negotiation because the donor was Cuban. [SLIDE 5] The story of Masdeu’s donation constitutes a similar case. In 2009, Frida Masdeu heard on NPR an interview with Professor Lillian Guerra. Masdeu was so impressed with the interview that she wrote down Guerra’s name, googled her, and emailed her. Masdeu told Guerra that she had in her possession the letters that her father Carlos González Blanco wrote to Masdeu and her mother while he was a political prisoner in Cuba. Masdeu and Guerra then started communicating and befriending each other. At the time, Masdeu was suffering from extreme depression and was considering suicide, but even then she knew she wanted to find a suitable repository for her letters. Upon establishing contact with Guerra, and later with VargasBetancourt, Masdeu understood the importance of her legacy and began to recover.9 Like in the case discussed above, the language and cultural connection between the donor and UF’s representatives (in this case a professor and an archivist) was a key factor in the negotiation of the gift. Moreover, Masdeu contacted the Libraries with another political prisoner, Reina Peñate 8 http://www.library.ufl.edu/spec/manuscript/guides/pupo.htm 9 Email from Frida Masdeu to the author, April 29, 2013. 4 de Tito who, in turn, donated the memoirs she had written on her experience.10 Needless to say, the finding aids for these collections are bilingual.11 [SLIDE 6] The collaborative agreements that UF’s Libraries now have with two Cuban institutions - the Fundación Núñez Jiménez and the Biblioteca Nacional José Martí—has also given way to the exchange of digitized material. In December 2012, librarians Brooke Wooldridge (FIU), Laurie Taylor (UF), and Vargas-Betancourt went with Professor Guerra to Cuba. There, they presented Dr. Eduardo Torres Cuevas, Director of the National Library, a digital version of the Romero Family Papers Regarding José Martí, which includes a letter to María Mantilla, supposed daughter of José Martí, with a plan and design of the national library that would be built in Cuba to commemorate Martí.12 To have a Spanish finding aid of such collection made the gift meaningful. [SLIDE 7] The relationship between UF and Cuban institutions has also led to more visits from Cuban scholars, some of whom do not speak English. In April 2014, Dr. Ángel Graña, President of the Fundación Núñez Jiménez, visited UF. His visit coincided with the Libraries’ exhibit Revolucionarias: Women and the Formation of the Cuban Nation, curated by Guerra and 10 http://www.library.ufl.edu/spec/manuscript/guides/penatedetito.htm 11 http://www.library.ufl.edu/spec/manuscript/guides/pupo_es.htm; http://www.library.ufl.edu/spec/manuscript/guides/gonzalezblanco_es.htm; http://www.library.ufl.edu/spec/manuscript/guides/penatedetito_es.htm 12 http://web.uflib.ufl.edu/spec/manuscript/guides/romero_es.htm 5 Vargas-Betancourt. This was the first exhibit to include bilingual labels, a fact appreciated by Dr. Graña who does not speak English.13 The collections described here document an important part of Cuban history, that related to the Cuban Revolution and the counterrevolutionary movements that followed it. To provide fair access to Spanish-speaking researchers, Spanish finding aids are essential. However, the process faces several obstacles. So far, only the higher level of description has been translated to Spanish. In other words, only the descriptive summary, the biographical/historical note, the scope and content, and other administrative information is translated, but the actual description of contents (series, subseries) is not. Consequently, access to archival material, even when this is in Spanish, continues to be limited. The main reason for not translating contents is the lack of sufficient specialized labor. This also explains the difficulties of translating existing finding aids for collections that have bilingual content, such as the Braga Brothers Collection. A similar problem exists in the digital content available in the Digital Library of the Caribbean (dLOC). Although the interface is in three languages (English, Spanish, and French), the metadata is only in English. Nonetheless, the production of Spanish finding aids (even if only at the higher description level) is a first step towards expanding access to UF’s multilingual special collections. A future step will be to experiment with other languages such as French and Haitian Creole for our Haitian collections. [SLIDE 8] 13 http://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00020264/00004 6