105C - American Bar Association

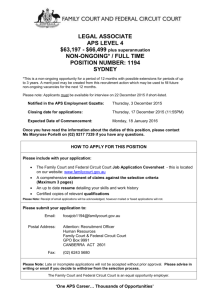

advertisement

105C AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION ADOPTED BY THE HOUSE OF DELEGATES AUGUST 11-12, 2014 RESOLUTION RESOLVED, That the American Bar Association urges that states and territories adopt judicial disqualification and recusal procedures which: (1) take into account the fact that certain campaign expenditures and contributions, including independent expenditures, made during judicial elections raise concerns about possible effects on judicial impartiality and independence; (2) are transparent; (3) provide for the timely resolution of disqualification and recusal motions; and (4) include a mechanism for the timely review of denials to disqualify or recuse that is independent of the subject judge; and RESOLVED FURTHER, That the American Bar Association urges all states and territories to provide guidance and training to judges in deciding disqualification/recusal motions. 105C REPORT Introduction Assuring fair and impartial courts, essential to preserving justice and the Rule of Law, remains a paramount objective of the structure and process of our justice system. To assure that laudable goal, judges must act without regard to the identity of parties or their attorneys, the judge’s own self-interest, or the likely criticism any decision might engender. To eliminate any perception of bias, the law has long recognized recusal or disqualification as a means to assure fundamental fairness. Although a number of specific prohibitions are found in the Model Code of Judicial Conduct and in various statutes, rules, and codes adopted in the States, there is widespread acceptance as well of the general standard that disqualification is warranted when a “judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned.”1 Increases in the amount of money expended in judicial elections, both by a judicial candidate’s own campaign and by independent interests, have heightened concerns about the potential for bias in the courts and can adversely affect the public’s confidence that judicial decisions not be influenced, even subtly, by elements external to the merits of the case. While the phenomenon of increased spending in what were once relatively quiet campaigns for judicial office has grown lately, recent decisions invalidating campaign finance laws, such as Citizens United v. Fed. Election Comm’n, 558 U.S. 310 (2010) and McCutcheon v. Fed. Election Comm’n, 134 S.Ct. 1434 (2014), suggest that the role of money in judicial selection may continue to grow and require that greater attention be paid to how disqualification, when warranted, ought to take place. In Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co., Inc., 556 U.S. 868 (2009), considering a state supreme court justice’s denial of a party’s recusal motion, the Supreme Court held that due process requires recusal2 when “there is a serious risk of actual bias—based on objective and reasonable perceptions—when a person with a personal stake in a particular case had a significant and disproportionate influence in placing the judge on the case by raising funds or directing the judge’s election campaign when the case was pending or imminent.” Id. at 884. That holding created a conceptual framework for thinking about recusal, but also recognized that “[n]ot every campaign contribution by a litigant or attorney creates a probability of bias that requires a judge’s recusal.” Id. Responding to the Caperton decision, the House of Delegates approved Resolution 107 in August 2011, which asked the Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility and the Standing Committee on Professional Discipline “to consider what amendments, if any, See, e.g., MODEL CODE OF JUDICIAL CONDUCT [hereinafter “Model Code”] R. 2.11(A) (2013). This concept is also reflected in federal law and the laws of 47 states. Deborah Goldberg, et al., The Best Defense: Why Elected Courts Should Lead Recusal Reform, 46 Washburn L.J. 503, 518 (2007). 1 The terms “disqualification” and “recusal” are often used interchangeably. See Hendrix v. Sec’y, Fla. Dep’t of Corrections, 527 F.3d 1149, 1152 (11th Cir. 2008). Technically, however, “recusal” refers to a judge’s decision to withdraw sua sponte, while “disqualification” refers to a ruling on a motion asking the judge to withdraw from hearing a particular case. See Forrest v. State, 904 So.2d 629, 629 n.1 (Fla. 4th D.C.A. 2005). 2 1 105C should be made to the ABA Model Code of Judicial Conduct or to the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct to provide necessary additional guidance to the states on disclosure requirements and standards for judicial disqualification.” Those committees proposed changes to Rule 2.11 of the Model Code of Judicial Conduct, which were designated as Resolution 108 for the 2012 Annual Meeting. The proposals, however, engendered opposition largely because the language suggested that judges were responsible to investigate and determine, sua sponte, whether outsized campaign contributions or expenditures, even independent expenditures by separate organizations made outside of the knowledge or control of judges, warranted recusal. Such an expectation, particularly in an era of limited judicial resources and statutes in some states that prohibited judges from knowing who has contributed to their own campaigns, was not the intent of the sponsors of Resolution 108, but language that made that intent clear in a manner satisfactory to all interested parties proved elusive. Responding to a resolution approved by the Conference of Chief Justices (CCJ) in July 2013, both Resolution 108 and a competing measure, designated as Resolution 10B and cosponsored by the Judicial Division (JD) and the Indiana State Bar, were withdrawn to permit CCJ to participate in the process of considering new language. In meetings held in Chicago in September 2013 and February 2014, representatives of the Standing Committees, the JD, and CCJ met to discuss possible approaches, agreeing that a resolution that addressed procedural issues in seeking judicial recusal had risen in priority and required the development of the principles now reflected in the present resolution. Background The Massachusetts Constitution, authored by John Adams in 1780, declares it the “right of every citizen to be tried by judges as free, impartial and independent as the lot of humanity will admit.” Mass. Const. Pt. 1, art. 29. The Massachusetts provision reflects a goal shared across states and the nation as a whole. Under the federal Constitution, due process plays the key constitutional role in assuring fair and impartial courts. See In re Murchison, 349 U.S. 133, 136 (1955). The importance of assuring judicial neutrality is not solely important to litigants; it is crucial to public confidence that the rule of law still prevails. In the states, judicial disqualification may be governed by such diverse sources as constitutional provisions, statutes, court rules, judicial precedent, codes of judicial conduct, ethical rulings, and administrative directives. While many of these provisions detail the instances in which recusal is appropriate or mandatory, as Ninth Circuit Judge Margaret McKeown has written, “[i]n most cases, the issue is not an actual conflict of interest or a claim of actual bias, but rather the appearance of potential bias in hearing a case where a judge’s impartiality is perceived to be in doubt.” M. Margaret McKeown, Don’t Shoot the Canons: Maintaining the Appearance of Propriety Standard, 7 J. App. Prac. & Process 45, 45 (2005). It is therefore critical that timely procedures be in place to permit a party to move for disqualification, receive a timely decision, understand the basis for the decision, and, when warranted, be permitted to seek timely review, without having first to litigate the case to a final disposition before receiving the relief that due process affords. As with the standards governing disqualification generally, states handle the process of disqualification differently. About a third of the states have a system of peremptory disqualification that allows litigants to seek a new 2 105C judge without a show of cause. Michelle T. Friedland, Disqualification or Suppression: Due Process and the Response to Judicial Campaign Speech, 104 Colum. L. Rev. 563, 615 (2004). However, procedures vary within states and even between civil and criminal trials, as well as jury and bench trials. Goldberg, 46 Washburn L.J. at 517. Where disqualification is for cause, the differences between states “tend to be procedural, not substantive.” Id. at 522. Observers have detailed some of these differences: Some courts require the challenged judge to transfer these motions immediately to a colleague (a presiding judge or chief judge chooses which colleague); some require transfer only after the challenged judge has ensured the motion’s timeliness and sufficiency; the rest let the challenged judge decide on these motions herself. Most state and federal courts, including the Supreme Court, follow the latter policy and rarely, if ever, require transfer. Nor is voluntary transfer typical. Likewise, while some jurisdictions encourage or require challenged judges to hold evidentiary hearings, most leave the decision of whether to do so entirely to the judge’s discretion. With or without hearings, judges in most--though again, not all--jurisdictions do not need to give a reasoned explanation for their recusal decisions. In practice, judges have been much more likely to give reasons when they decline to recuse themselves. Id. at 523 (footnote omitted). The objective of this resolution is not to seek uniformity of procedure across states or even across different levels of courts within a state, but to assure that certain key concepts are followed in resolving disqualification disputes. Explanation of the Resolution First, the Resolution puts the American Bar Association on record as supporting a disqualification process that is clearly articulated, transparent, and timely. It is axiomatic that a process designed to assure fairness and impartiality in the judiciary must be spelled out with sufficient specificity and concreteness that no one could complain afterwards that no understandable path to raise the issue and see it resolved exists. Nor should a litigant or counsel have to guess at the process by which a decision on a motion to disqualify is considered. Transparency is both an end itself and a means by which fairness and efficiency is promoted. It assures that reviewable reasons are expressed on the recusal decision. Timeliness is also essential to a system of justice. Our Due Process clauses derive from Magna Carta’s Chapter 40, which promised: “To no one will we sell, to no one will we refuse or delay, right or justice.” Here, timeliness anticipates that the recusal issue will be fully resolved before the time and expense of trial or briefing and argument occur through a timely motion and by frontloading the process and permitting some form of interlocutory review, whether by a higher court or by another authority independent of the subject judge. This portion of the resolution also conceptually adopts the principal elements found in every enunciation of the grounds for recusal: actual conflict or bias, other impropriety, and the appearance of impropriety. It further calls attention to the modern reality of campaign spending by “recognizing certain campaign expenditures and contributions, including independent 3 105C expenditures, made during judicial elections raise concerns about possible effects on judicial impartiality and independence.” Second, understanding that in many instances state procedures permit a motion for disqualification to be considered by the judge who is the subject of the motion, the resolution urges that procedures be put in place that would allow for independent review of an order denying the motion. Such a procedure recognizes the difficulty anyone has in judging a matter in which he or she is accused of having a potential bias. See, e.g., The Federalist No. 10, p. 59 (J. Cooke ed. 1961) (J. Madison) (“No man is allowed to be a judge in his own cause; because his interest would certainly bias his judgment, and, not improbably, corrupt his integrity.”). Still, a judge who denies a motion to disqualify, even when later overturned, generally does not do anything improper. The Caperton Court recognized that “inquiring into actual bias . . . is often a private [inquiry].” Caperton, 556 U.S. at 883. Yet, it is not difficult to imagine the situation where a judge “simply misreads or misapprehends the real motives at work in deciding the case.” Id. The question that must be answered, then, is “not whether the judge is actually, subjectively biased, but whether the average judge in his position is ‘likely’ to be neutral, or whether there is an unconstitutional ‘potential for bias.’” Id. at 881. Timely review by someone other than the subject judge thus assures that a decision against disqualification is not personal, but reflects a reasonable judge standard. While the judge asked to recuse may honestly believe that he or she can hear a matter and come to a fair and impartial decision, believe that any appearance of bias is too attenuated to act upon, and believe that the more important judicial value at stake is the duty to sit, the availability of independent review will further assure litigants and the public of a full and fair consideration of the potential for bias. Finally, the Resolution urges all states and territories to provide guidance and training to judges in deciding motions to recuse. To assure that judges understand the requirements imposed by due process and state law and achieve a measure of uniformity in the determinations made on recusal, educational programs and other forms of training are helpful and ought to be conducted. Respectfully submitted, Eugene G. Beckham, Chair Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section August 2014 4 105C GENERAL INFORMATION FORM Submitting Entity: ABA Tort Trial & Insurance Practice Section Submitted By: Eugene G. Beckham, Chair 1. Summary of Resolution(s). This resolution follows up on Resolution 107, passed at the 2011 Annual Meeting, by urging states to establish clearly articulated procedures that assure that properly made motions to disqualify a judge for a conflict of interest receive timely consideration, grounds for the decision on the motion are transparent, and immediate independent review of the decision be available, before the time and expense of a case’s merits is engaged. 2. Approval by Submitting Entity. Approved by the Council of the Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section on May 1, 2014. 3. Has this or a similar resolution been submitted to the House or Board previously? No. While this resolution has some overlap with Resolution 107, that is both a necessity of the subject matter and the process by which this resolution was drafted, incorporating concerns expressed by the Conference of Chief Justices and by the proponents of previous competing resolutions that were ultimately withdrawn from consideration by the House. 4. What existing Association policies are relevant to this Resolution and how would they be affected by its adoption? The proposed resolution is consistent with existing Association policies, but expands upon them. These policies are: In August 1999, the ABA House of Delegates adopted Resolution 123, which included revisions to Canon 3 of the Model Rules of Judicial Conduct and adopted an approach that would have judicial candidates limit the size of contributions accepted in order to reduce the instances in which recusal would be necessary. Model Rule 2.11, part of the Model Code of Judicial Conduct adopted by the House in February 2007, addresses judicial disqualification and provides a judge should disqualify himself or herself when a “party, a party’s lawyer, or the law firm of a party’s lawyer has” made aggregate contributions in an amount greater than a number set by state law. In August 2011, the House adopted Resolution 107, which urged states to establish procedures for judicial disqualification determinations and prompt review of denials of requests to disqualify. 5 105C 5. What urgency exists which requires action at this meeting of the House? The issues represented by this resolution were the product of discussions between representatives of different groups that previously proposed competing judicial disqualification resolutions to the House and which were withdrawn, most recently, because of objections advanced by the Conference of Chief Justices. The resolution proposed is consistent with concepts that each of the stakeholder groups approved. 6. Status of Legislation. (If applicable) Not applicable 7. Brief explanation regarding plans for implementation of the policy, if adopted by the House of Delegates. Appropriate notice to relevant policymakers would be made. In addition, if adopted, the Section plans to inform and educate judges and local jurisdictions about the Resolution and Report. 8. Cost to the Association. (Both direct and indirect costs) None 9. Disclosure of Interest. (If applicable) None 10. Referrals. Judicial Division Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility Standing Committee on Professional Discipline Standing Committee on Judicial Independence Section of Litigation 6 105C 11. Contact Name and Address Information. (Prior to the meeting. Please include name, address, telephone number and e-mail address) Robert S. Peck Center for Constitutional Legislation 777 6th St. NW, Ste 520 Washington, DC 20001 202/944-2874 FAX: 202/965-0920 E-mail: Robert.peck@cclfirm.com 12. Contact Name and Address Information. (Who will present the report to the House? Please include name, address, telephone number, cell phone number and e-mail address.) Robert S. Peck Delegate, TIPS 202/944-2874 (o) 202/27-6006 (c) E-mail: Robert.peck@cclfirm.com 7 105C EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Summary of the Resolution This resolution calls for states and territories to adopt transparent and timely procedures to ensure that judges disqualify or recuse themselves that take into account the fact that certain campaign expenditures and contributions, including independent expenditures, made during judicial elections raise concerns about possible effects on judicial impartiality and independence. It further urges the adoption of a mechanism for the timely review of denials to disqualify or recuse that is independent of the subject judge. 2. Summary of the Issue that the Resolution Addresses The resolution recognizes that grounds for recusal or disqualification could exist when certain large campaign expenditures and contributions, including independent expenditures, are made during judicial elections, because those expenditures or contributions may raise concerns about judicial impartiality and independence. Too often, decisions about recusal are made solely by the judge who is the subject of the motion to recuse, without any articulation of the basis for denial of such a motion or any form of independent review. The resolution urges states and territories to adopt procedures that will enable litigants to make timely motions, receive timely determinations of those motions, and prompt independent review of the denial of any motion. 3. Please Explain How the Proposed Policy Position will address the issue By articulating the principles that must be in place to assure fair and impartial justice in light of the potential for bias that reasonable people may view as a result of outsized campaign contributions or expenditures and urging states and territories to provide guidance and training to judges in deciding such motions, the proposed policy advances previous ABA resolutions on the issue. 4. Summary of Minority Views The co-sponsors are not aware of any minority views or opposition. 8