PV-Blog - Mad In America

advertisement

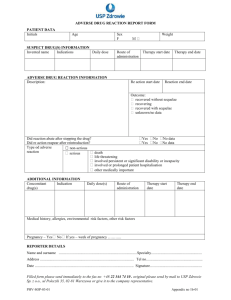

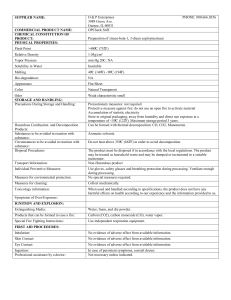

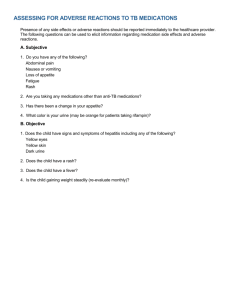

Meyboom, RHB., Egberts, ACG., Edwards, IR, Hekster, Y,A., Konig, FHP. & Gribnau, FWJ. 1997 Principles of Signal Detection in Pharmacovigilance. Drug Safety 16(6) 355-365. Clinical trials are inherently limited in their ability to produce data regarding adverse effects, especially when these are rare and unexpected. Therefore, at the time of marketing of a drug, the knowledge of its tolerabiltiy is inevitably incomplete. Druing the years following the launch of a drug, this knowledge of its tolerability is ineviably incomplete. During the years following the launch of a drug, this knowledge usually increases, for example, with regard to pharmacology, clinical use and adverse effects.1 Clinical trials (phase III and IV) are especially effective in providing information on type A adverse effects. Characteristically, they combine qualitative with quantitative data, but their use is inhrently restricted to effects with high frequency and a short induction time.2 Despite clinical trials prior to licensing, rare or delayed ADRs are often unknown at the time a pharmaceutical product enters the market. This is because such trials are limited in time and number of patients, usually have an efficacy rather than safety focus, and are usually performed in selected patient groups. New Zealand (NZ) implemented a national surveillance scheme in 1965 and was one of the founding members of the World Health Organization (WHO) International Drug Monitoring Programme when it was established in 1968. Today, the ‘New Zealand Pharmacovigilance Centre’ (NZPhvC) is the national centre responsible for monitoring adverse reactions to therapeutic products in NZ. The aims of the NZPhvC are to identify any side effects of a medicine as early as possible; to determine the frequency of such adverse effects and which patient groups may be at highest risk of the adverse event; and to report these findings to Medsafe which in turn takes appropriate action leading to the safer use of medicines in NZ. The reports are prioritised, so that the more serious adverse events receive early Died—due to adverse reaction Died—drug may be contributory Died—unrelated to drug Died Unknown 1 Meyboom, RHB., Egberts, ACG., Edwards, IR, Hekster, Y,A., Konig, FHP. & Gribnau, FWJ. 1997 Principles of Signal Detection in Pharmacovigilance. Drug Safety 16(6) 355-365 2 Meyboom, RHB., Egberts, ACG., Edwards, IR, Hekster, Y,A., Konig, FHP. & Gribnau, FWJ. 1997 Principles of Signal Detection in Pharmacovigilance. Drug Safety 16(6) 355-365 Spontaneous reporting limitations Under-reporting—major weakness of all spontaneous reporting systems Selective reporting due to differing thresholds for reporting amongst health professionals (reporting bias) Lack of denominator for events so not able to provide incidence rates Poor at detecting delayed ADRs Rates of reporting influenced by publicity With regard to your request for more information on suicides with antidepressants the data previously provided for an OIA was as follows: How many people in New Zealand have committed suicide between June 2001 and June 2011 while being prescribed Amitriptyline One report Clomipramine hydrochloride No reports Doxepin hydrochloride One report Dothiepin hydrochloride No reports Imipramine hydrochloride No reports Maprotiline hydrochloride No reports Mianserin hydrochloride No reports Nortriptyline hydrochloride No reports Phenelzine sulphate No reports Tranylcypromine sulphate No reports Moclobemide No reports Citalopram hydrobromide One report Fluoxetine hydrochloride Two reports Escitalopram No reports Setraline No reports Paroxetine hydrochloride Five reports Venlafaxine One report Mirtazapine No reports Table : Source of spontaneous reports 2007-2011 Reporter Type % of 5 Years Total GP 24.90 Hospital Doctor 11.64 Hospital Pharmacist 4.26 Community Pharmacist 8.23 Nurses 22.74 Other HCPs 2.82 Pharmaceutical Company 16.10 Public 1.61 Other 7.70 From the total number of spontaneous reports with suicidal behaviour or suicide reaction terms 71.5% have been assessed as Causal. Table : Number of reports per year with reaction term “Suicide” Year Report Received Number of Reports 1993 1 1994 1 1995 2 1998 1 1999 1 2000 1 2001 6 2002 2 2003 2 2004 3 2005 3 2006 1 2007 3 2008 3 2009 10 2010 3 2011 3 Thank you for contacting me. Answers to your questions below are as follows: Reporting rate: New Zealand, along with more than 100 other countries, is a member of the WHO National Centres group. All of these countries send anonymised copies of adverse reaction reports to the WHO International Collaborating Centre in Uppsala Sweden on a regular basis. The reporting rate is then calculated on a six-monthly basis by the WHO Uppsala Collaborating Centre based on the number of reports from the individual country and that country’s population. New Zealand was one of the founding member countries of the WHO International collaboration and one of the first countries to set up an adverse reactions reporting centre (1965) so reporting is well established here. Over time, other countries have improved their reporting rates and in 2010 New Zealand was relegated to second place by Singapore. Reporters: In the past, GPs have been the main group of reporters, however the numbers now show Nurses as the largest group but this can be attributed to Practice Nurses completing the forms on-line for the GPs and Immunisation Nurses sending in adverse reaction reports for vaccines. I have attached a pdf showing the proportions over the years 2006 to 2011. Specialists operating in a Hospital setting are included in the ‘Hospital Doctor’ group while private Consultants are included in the ‘Other HCPs’ group. We are unable to identify the individual ‘Specialties’. You will note there was a large number of reports from the ‘Public’ and ‘Other’ in 2008 and this was due to the heightened public and media awareness of the Eltroxin product. Enhanced Consumer Reporting: CARM has always accepted reports from Consumers and in the past year we have included an online reporting form on our website which does not require a User and Password login (previously required and only health professionals were accepted). We have not actively promoted this option though as we do not have the resources to deal with a large increase in report numbers should it occur. Regards Janelle Janelle Ashton Manager Information Systems NZ Pharmacovigilance Centre DDI: +64-3-4799043 FAX: +64-3-4797150 Email: Janelle.ashton@otago.ac.nz F15.1 = Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of other substances (alcohol) Z91.5 = Suicide attempt From: To: Subject: RE: Date: Mon, 26 Sep 2011 04:28:58 +0000 Toran janelle.ashton@otago.ac.nz taiwhenua1@hotmail.com Henry Dear Maria We have been advised by the Ministry of Health that apparently there was an oversight in our previous email correspondence to you in so far as we omitted to provide you with a copy of the entry in the CARM database The CARM database does hold reports of suicide and suicidal tendency with the SSRI’s and by way of example over the history of use of Fluoxetine in New Zealand there are 9 reports each of suicidal tendency and suicide attempt and 3 reports of suicide. Considering that SSRI’s are prescribed for depression and as covered in the two extracts mentioned, it is not possible in these reports to conclude that fluoxetine was a causal factor just as much as the possibility that worsening depression in the early stages of treatment may be a factor. Once again please accept my apologies for this late response. With best wishes Michael Dr Michael Tatley Director: New Zealand Pharmacovigilance Centre and Centre for Adverse Reactions Monitoring Dunedin School of Medicine University of Otago In the 1950s a brave American woman called Frances Kelsey did something I have come to learn is rare in the world of drug regulation. She stood up against the pressure of a large pharmaceutical company and refused to approve its drug because she had concerns that its clinical trials were not sufficiently robust to provide a satisfactory level of evidence that the drug they wanted to market was safe. This company had conducted clinical trials that were poorly designed and ignored any results that did not show the drug in a good light. The drug was launched on the British market for example, two months after the researcher advised “it would seem unjustifiable to use the drug for long term therapy, pending the results of more detailed study of its long term effects in a larger series of patients.” This company did not conduct tests on adverse reactions in pregnant women but marketed their drug to prescribers as safe for both pregnant women and their babies and ignored reports that the drug produced a wide range of adverse reactions which mirrored the results from its own trials. It pushed its "completely nonpoisonous, completely safe" campaign in 50 advertisements in major medical journals, 200,000 letters to doctors around the world, and 50,000 circulars to pharmacists. By the end of the first year, sales had reached 90,000 packets per month. The drug found its way to all comers of the globe including 11 European, 7 African, 17 Asian, and 11 North and South American countries. When a well known specialist, wrote asking whether the company had any knowledge of the drug’s effects on the nervous system, despite reports to the company about such effects the drug company replied "Happily, we can tell you that such disadvantageous effects have not been brought to our notice." Through connections with a friendly editor of a medical magazine, the company successfully delayed publication of a paper which showed a strong link between the drugs use and a serious adverse reaction. An internal company memo read "Sooner or later we will not be able to stop publication of the side effects. We are therefore anxious to get as many positive pieces to work as possible." Four years after the drug hit the market, nearly 64 million tablets had been prescribed and the company was sending pamphlets to doctors claiming that it could “be given with complete safety to pregnant women and nursing mothers without adverse effect on mother or child." The drug Frances Kelsey refused to approve was Thalidomide. Following the Thalidomide disaster, adverse reaction monitoring programmes were established by the World Health Organisation in recognition of the fact that clinical trials are a very poor vehicle for identifying potentially disastrous adverse reactions and that the real testing for adverse effects commences once the drug is unleashed on an unsuspecting public. The Journal of Drug Safety explains Clinical trials are inherently limited in their ability to produce data regarding adverse effects, especially when these are rare and unexpected. Therefore, at the time of marketing of a drug, the knowledge of its tolerabiltiy is inevitably incomplete. Druing the years following the launch of a drug, this knowledge of its tolerability is ineviably incomplete. Pharmacovigilance, according to the WHO is “the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other drug-related problem.” Both the World Health Organisation and the New Zealand Government promote the view that New Zealand has one of the best pharmacovigilance programmes in the world. The combination of spontaneous reporting, intensive medicines and vaccine monitoring, the performance of causality assessments for all reports received and feedback to reporters are amongst the features of our system that are credited with our apparently having the highest adverse reporting rate in the world. So, with an international pharmacovigilance programme in place the events that led to the Thalidomide disaster couldn’t happen again could they? And New Zealanders, having such a superior pharmacovigilance programme should be safer than most when it comes to adverse drug reactions, right? How would we measure that? Well according to the WHO the aims of PV are “to enhance patient care and patient safety in relation to the use of medicines; and to support public health programmes by providing reliable, balanced information for the effective assessment of the risk-benefit profile of medicines.” So does New Zealand have a superior record in patient care and safety in relation to medicine use? Does it inform its public health programmes with reliable, balanced information based on effective risk-benefit assessment of medicines? In a word…No . In several words, the evidence is that we actually do worse on these measures than other countries. According to Medsafe, New Zealand reports approximately 5% of all adverse reactions. Their evidence of this? That our adverse reaction reports are higher than other countries per head of population. In fact, it is entirely possible that in fact we have a higher rate of adverse reactions to medication than other countries. Perhaps because we have high prescribing rates, significant populations of people from ethnic groups with higher prevalence of genetic variations which influence the metabolism (and therefore the adverse reaction rates) and a host of other factors. In response to an information request to the Chief Coroner, a TV journalist was advised that while Coroner’s do not systematically gather or record data on medication use of suicide victims, there is evidence that "Of the 497 deaths ruled as suicide in the 2008 calendar year, 162 had been prescribed some sort of anti-depressant, anti-psychotic or anti-anxiety medication at the time of their death." That’s a third of all suicide victims and does not include those where no information was gathered by the coroner, where the victim was withdrawing from the drug or where other drugs such as anti-acne and smoking cessation drugs strongly linked with suicide, were being prescribed. So in what proportion of those cases did a medical professional report a suspected adverse reaction to our pharmacovigilance agency CARM? Data provided by Dr Michael Tatley, director of CARM shows that in 2008 CARM received 3 reports of Adverse reactions containing the reaction term ‘suicide.’ That is, 1.85% of the most conservative estimate of suicides that year, who had current prescriptions for psychiatric drugs with known links to suicide, were reported to CARM. My son hanged himself that year, 15 days after being prescribed fluoxetine. The trainee psychiatrist who prescribed the drug did not report a suspected adverse reaction to CARM. Neither did that the consultant psychiatrist who was his superviser, another consultant psychiatrist who was assigned to oversee his care, any of the six other psychiatrists who reviewed his file prior to his inquest, the psychiatrist who was the clinical director of the clinic he attended, his GP or any other medical professional involved in his care. His mother reported but her report fell through the cracks and as a result of an oversight, she was not provided with an acknowledgement of its receipt, a causality assessment or data on other suicides on the drug until 3 and a half years after his death – conveniently after the inquest into his death had been completed and the causality assessment could not be used as evidence to support recommendations the Coroner might make to prevent future suicide deaths. SSRI antidepressants and severe agitation, severe restlessness/akathisia, and/or increased suicidality “The removal of these reactions has been recommended by the MARC due to a good level of prescriber awareness having been achieved.” 5