Ed Charmley - Carbon Farming Knowledge

advertisement

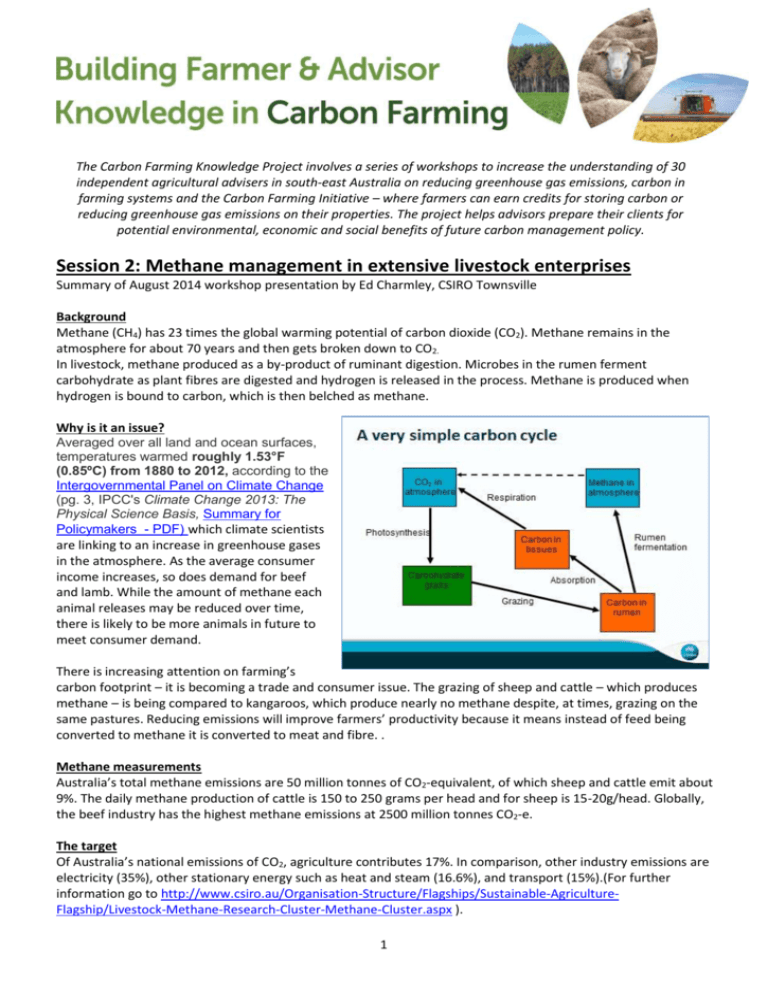

The Carbon Farming Knowledge Project involves a series of workshops to increase the understanding of 30 independent agricultural advisers in south-east Australia on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, carbon in farming systems and the Carbon Farming Initiative – where farmers can earn credits for storing carbon or reducing greenhouse gas emissions on their properties. The project helps advisors prepare their clients for potential environmental, economic and social benefits of future carbon management policy. Session 2: Methane management in extensive livestock enterprises Summary of August 2014 workshop presentation by Ed Charmley, CSIRO Townsville Background Methane (CH4) has 23 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide (CO2). Methane remains in the atmosphere for about 70 years and then gets broken down to CO2. In livestock, methane produced as a by-product of ruminant digestion. Microbes in the rumen ferment carbohydrate as plant fibres are digested and hydrogen is released in the process. Methane is produced when hydrogen is bound to carbon, which is then belched as methane. Why is it an issue? Averaged over all land and ocean surfaces, temperatures warmed roughly 1.53°F (0.85ºC) from 1880 to 2012, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pg. 3, IPCC's Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis, Summary for Policymakers - PDF) which climate scientists are linking to an increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. As the average consumer income increases, so does demand for beef and lamb. While the amount of methane each animal releases may be reduced over time, there is likely to be more animals in future to meet consumer demand. There is increasing attention on farming’s carbon footprint – it is becoming a trade and consumer issue. The grazing of sheep and cattle – which produces methane – is being compared to kangaroos, which produce nearly no methane despite, at times, grazing on the same pastures. Reducing emissions will improve farmers’ productivity because it means instead of feed being converted to methane it is converted to meat and fibre. . Methane measurements Australia’s total methane emissions are 50 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent, of which sheep and cattle emit about 9%. The daily methane production of cattle is 150 to 250 grams per head and for sheep is 15-20g/head. Globally, the beef industry has the highest methane emissions at 2500 million tonnes CO2-e. The target Of Australia’s national emissions of CO2, agriculture contributes 17%. In comparison, other industry emissions are electricity (35%), other stationary energy such as heat and steam (16.6%), and transport (15%).(For further information go to http://www.csiro.au/Organisation-Structure/Flagships/Sustainable-AgricultureFlagship/Livestock-Methane-Research-Cluster-Methane-Cluster.aspx ). 1 The Australian Government’s target is to reduce emissions by 5% of 2000 levels by 2020. The challenge for agriculture is to meet the target without compromising food security. While the financial incentive for reducing methane is currently small, there are productivity incentives. Also, the future value of carbon is not known but is likely to be higher than current estimates. Management options There are a range of options to reduce methane emissions. Some are easy to put in to practice but have a lower overall impact on emission reductions, while others will take longer to implement but may have a higher impact. Dietary additives Feeding fats and oils can reduce emissions by 3-4%. These include canola, soybean, sunflower, fish/sunflower oil and flaxseed oil. This is recognised under the Carbon Farming Initiative for the dairy industry methodology (for further information go to http://www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/Carbon-Farming-Initiative/Fact-sheets-FAQsand-guidelines/Publications/Pages/Default.aspx#Dairy-feed-additives). The oil interferes with the microbes and their ability to produce methane. However, for sheep and cattle, the economic viability of undertaking this carbon farming activity would be lower than for dairy. Feeding nitrates, such as calcium nitrate, reduces emissions. Nitrates reduce methane production by providing an alternative chemical pathway for hydrogen as the rumen breaks down plant fibres. This can be as nitrate-based feed supplement blocks. For every 62g of nitrate fed, methane would be reduced by 16g, or about 8%. Typically, animals on a supplement block would eat only half that so, practically, reductions would be about 4%. The safe feeding rate is very low, about 1% of diet at about 100g/head/day. For further information go to http://www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/Carbon-Farming-Initiative/methodologydeterminations/Pages/default.aspx In northern Australia, feeding leucaena, a northern forage legume shrub, is reducing emissions. The tannins in the leaves reduce the amount of methane in the rumen by affecting the microbial activity. Research is continuing into feeding seaweed to reduce emissions. However, the one unanswered question of reducing methane is its impacts on rumen efficiency. %). (For further information go to http://www.csiro.au/OrganisationStructure/Flagships/Sustainable-Agriculture-Flagship/Livestock-Methane-Research-Cluster-Methane-Cluster.aspx) Improve productivity One goal behind reducing emissions intensity is increasing productivity through improved feed conversion. The end result can be improved weaning rate, weaning weight and rate of gain. Retailers may benefit because meat may be cheaper for consumers and farmers may receive credits for it. The price of carbon is not as important as the fact that farmers can be more efficient. Genetics Through genetic selection, farmers can reduce the methane-emitting capacity of their flocks and herds. Researchers have found some animals are more efficient feed converters because they have more active rumen microbes, producing less methane. This trait – called the Residual Feed Intake (RFI) – is heritable. It is estimated that there could be a 15% reduction in methane emissions per animal over 25 years by selecting low RFI sires. One of the benefits is that it is built into the animal – there is no extra dosing or feeding – and the effects are cumulative. But one of the issues is that selecting for methane via lower RFI may inadvertently select against other economically-important traits. 2 Rumen manipulation Research is continuing into the different reactions between microbes and how the rumen deals with hydrogen when breaking down plant fibres. One possible option is manipulating the rumen so that surplus hydrogen is stored in volatile fatty acids that are another product of rumen fermentation. Useful resources The National Greenhouse Gas Inventory – ageis.climatechange.gov.au The Carbon Farming Initiative – www.mycfi.com.au Building Farmer and Advisor Knowledge in Carbon Farming Project – www.carbonfarmingknowledge.com.au More information: Ed Charmley, 0408 771 616, ed.charmley@csiro.au This project is supported with funding from the Australian Government 3