2015 PI Symposium Jenkins Handout

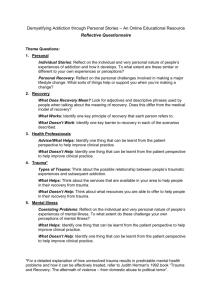

advertisement