Strauss AW, Powell CK, Hale DE, Anderson MM, Ahuja A, Brackett

advertisement

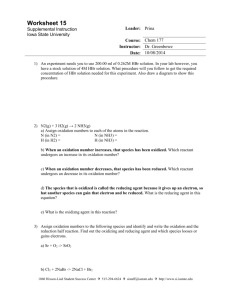

Morgan Wardrop Potential of exercise testing for metabolic disorders of fatty acid oxidation Introduction Disorders of fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in humans were first recognized in 1973, and have been the subject of much research and discovery for the past few decades ( Rinaldo et al. 2002). FAO disorders have been linked with a variety of disease presentations, including Reye or Reye-like syndrome, rhabdomyolysis, liver disease and sudden infant death syndrome, to name a few. As a result of newborn screenings, many patients born with these genetic disorders can be spared the most severe symptoms associated with states of metabolic crisis, normally induced by fasting, exercise, cold or stress. However, many phenotypes require strict lifetime disease management, and gaps in understanding of disease function and potential therapies warrant much further research on this class of diseases. Overview of β-oxidation process Lipids constitute one of the major energy sources utilized by mitochondria within the cell. Lipids are released into the bloodstream as glycerol and fatty acids. Eventually, most of these products are either utilized by muscles for energy or are taken up by the liver. Through the β-oxidation cycle, fatty acids derived from lipids are broken down into a form that can be used to generate ATP. While β-oxidation in the inner mitochondrial space is most widely used for initiating lipid metabolism, it is important to note the alternatives; peroxisomes can also use βoxidation, and α-oxidation and ω-oxidation pathways for lipid metabolism also exist (Moczulski et al. 2009). Fatty acids prior to metabolic processing are classified by their carbon chain length, with short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) having <6 carbons, medium-chain FAs (MDFAs) having 61 10 carbons, long-chain FAs (LCFAs) having 12-20 carbons, and very long-chain FAs (VLCFAs) having >22 carbons (“Drugs, Disease, & Procedures” 2012) While SCFAs and MDFAs can pass freely through the inner mitochondrial membrane, LCFAs and VLCFAs are transported through the inner membrane via attachment to a carnitine. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPTI) sits on the inner side of the outer mitochondrial membrane and attaches acyl groups from coenzyme A to carnitine to form palmitoylcarnitine. A transferase then passes palmitoylcarnitine into the inner membrane, where it is separated again by CPTII. The reformed acyl-CoA is then catalyzed by VLCAD, or very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, for processing by mitochondrial trifunctional protein (MTP) into a medium-chain acyl-CoA. At this stage, the compounds can enter the β-oxidation cycle, which will yield acetyl-CoA for utilization in the citric acid cycle. Spectrum of disorders There are many stages at which the β-oxidation pathway can be interrupted; at the plasma membrane, during fatty acid transport, or during fatty acid oxidation. In this overview, we are specifically concerned with discussing the diseases of lipid oxidation. Further information on the other types can be found elsewhere ( van Adel and Tarnopolsky 2009) (Berardo et al. 2012). SCADD Short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (SCADD) is a deficiency of the enzyme responsible for the initial stages of C4-CoA oxidation (van Maldegem et al. 2010). It generally presents in patients before 5 years as developmental delay, but is also associated with a huge spectrum of other symptoms, including hypoglycaemia, behavioral disorders, epilepsy/seizures, 2 lethargy, myopathy, hypotonia, facial weakness, and many others reported solely in single patient or sibling case studies. Most symptoms will lessen or disappear completely with followup, and there seems to be no clear genotype-phenotype correlations identified, making this a particularly difficult disease to study. For perhaps the same reasons, newborn screening for SCADD has not gained much backing, and the disease is usually caught while investigating neurological abnormalities or hypoglycaemia in a young patient. MCADD At an incidence of 1:10K – 1:30 K (Grosse et al. 2006), the most common, and subsequently most studied, β-oxidation disorder in humans is medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Newborn screenings for the disease have revealed a significantly higher incidence than estimates from clinical diagnosis in northern Europe (Schatz and Ensenauer 2010). This is probably because, like other metabolic diseases, it presents with a variety of symptoms and severities. While most cases experience symptoms at an early age, if at all, adult presentations of the disease have also been known to occur, especially with metabolic crisis brought about by fasting and alcohol or drug use. In some studies, identification of the disease as a result of metabolic crisis induced mortality was as high as 25%. Classic symptoms of MCADD include hypoglycaemia, global developmental disabilities, behavioral abnormalities, encephalopathy, and rhabdomyolysis. Symptoms can be severely reduced through a high carbohydrate, low fat diet and the avoidance of fasting. LCHADD 3 LCHADD, or long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency, was identified in a Finish study as having an incidence of between 1:54K and 1:56K, although larger studies are required to consider this a standard rate (Baruteau et al. 2012). LCHADD is unique amongst this category of diseases for causing retinopathy (Autti-Rämö et al. 2005). It is also associated with peripheral neuropathy and maternal hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme, and low platelet count, or HELLP syndrome (Gillingham et al. 1999). It is also associated with more common FAO disorder symptoms, like hypoketotic-hypoglycaemia and acute myglobinuria. Success in controlling these symptoms is mostly due to long-chain fatty acid restriction and MCT-oil supplementation (Autti-Rämö et al. 2005). However, newborn screening or early identification of the disease upon the onset of symptoms is extremely important, as LCHADD typically presents for the first time within days of mortality without intervention (Sykut-Cegielska et al. 2011). Without screening, the overall mortality from this disease is estimated to be within 30-50%. VLCADD VLCADD, or very long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase disorder, affects many of the same types of fatty acids as LCHADD or carnitine palmitoyl-transferase II deficiency (CPTII) (Martìnez et al. 1997). However, VLCADD has the distinction of presenting in three rather varied phenotypes. These three are roughly classified as VLCADD with cardiac involvement (VLCAD-C), VLCADD with hepatic involvement (VLCAD-H), and VLCADD with muscular involvement (VLCAD-M). Spiekerkoetter et al. (2003) identified the incidence of VLCADD to be between 1:50K – 1:100K (Spiekerkoetter et al. 2003). VLCAD-C 4 This is typically the most severe form of the disease, often showing symptoms of cardiomyopathy at infancy (Roe et al. 2001). Some researchers have suggested this to be the form largely responsible for the premature death of VLCADD patient siblings at an early age during metabolic crisis (Moczulski et al. 2009) (Strauss et al. 1995). Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies, along hepatomegaly, are associated with this form of VLCADD. Often there is a need for hospitalization as a result of a metabolic crisis within the first few years of life. However, with modern screening, this can be limited or prevented through careful monitoring and dietary control. VLCAD-H VLCADD with hypoglycemia-induced symptomology, either hepatic or hypoketotic, is called VLCAD-H (Roe et al. 2001). This typically appears during infancy or childhood, and is typically mild compared to the VLCAD-C phenotype. There is no cardiac involvement at this form, although the hepatic involvement remains (Leslie et al. 2011). However, metabolic crisis can induce ketoacidosis and can even degrade into more severe symptoms, like cardiac arrest (Bonnet et al. 1999). Thus, this form also requires careful monitoring in the early stages of life. VLCAD-M VLCAD-M is typically the mildest form of VLCADD. It is characterized by late-onset of symptoms with muscular involvement, commonly in the form of exercise intolerance, pain/soreness, myoglobinuria and rhabdomyolysis induced by fasting, fever, cold, stress and prolonged exercise (Spiekerkoetter et al. 2009). While there is general no long-term effect of rhabdomyolysis episodes on patients, a small percentage of severe episodes will lead to renal failure, cardiac arrest, and death (Quinlivan et al. 2012). Thus, it is important not to 5 underestimate severe presentations of these symptoms. Additionally, it should be mentioned that although this phenotype is generally associated with adolescents and adults, it also regularly presents in children. As mentioned earlier, other phenotypes can transition overtime into VLCAD-M as well, making it the broadest category of this disease. Exercise testing to target fatty acid oxidation Cardiopulmonary exercise testing is typically used to provide insight into the causes of general fatigue and reduced exercise tolerance. However, the value of the diagnostic information provided by such tests can be quite substantial, especially in consideration of metabolic diseases effecting energy consumption. Some very valuable pieces of information to come out of these tests include anaerobic threshold (AT), respiratory exchange ratio (RER), peak of oxygen consumption (VO2peak), maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide output over time (VO2 and VCO2) from indirect calorimetry via breath-by-breath analysis, along with more typical physiological measurements like heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP), and echocardiogram (ECG) (Milani et al. 2006). In 2001, Jeukendrup et al. identified a new physiological parameter which could be measured through maximal exercise testing, called fatmax (Jeukendrup and Achten 2001). Fat oxidation should increase along with the intensity of an exercise to an extent, after which the body increasingly recruits type 2 muscle fibres and carbohydrate stores for energy. At this point, high rates of glycolysis inhibit mitochondrial fatty acid transport via carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1. The point at which the fat oxidation rate is maximized over the rate of glycolysis is referred to as the fatmax, or sometimes called lipoxmax. 6 Fatmax can be expressed in terms of HR, work rate, or most commonly, percent of VO2peak (%VO2peak). The calculation for fatmax is based off of the simple idea that the difference between VO2 and VCO2, measured via indirect calorimetry, helps to estimate the type of substrate being utilized for energy, assuming that VO2 uptake and VCO2 output originate purely from oxidative metabolic processes (Jeukendrup and Wallis 2005). Lipogenesis, gluconeogenesis, ketogenesis and protein degradation can complicate these measurements somewhat. As a result, carbon isotope tracing has found current methods to accurately estimate substrate oxidation, for both carbohydrates and fat, up to 80%-75%VO2max. A number of calculations have been proposed to measure fat oxidation from indirect calorimetry, with a variability of only about 3%. Therefore, this study chose to use the calculation proposed by Péronnet and Massicotte, as it is both accurate in estimating fat oxidation and does not require an estimate of protein degradation during exercise (Péronnet and Massicotte 1991). For adults, fatmax usually lies within 30-70% VO2peak, whereas children achieve fatmax at 35-65% VO2peak (Chenevière et al. 2011) (Chenevière et al. 2010). Many factors can affect an individual’s curve of fatmax, including gender, fitness level or training status (Tolfrey et al. 2010), and the type of machine the test is performed on (Zakrzewski and Tolfrey 2010). The ideal protocol for testing fatmax on a cycle ergometer was determined by Achten et al. to be 35 watts/3 minute intervals, which ensures a stable state at each interval while minimizing duration of exercise (Achten et al. 2002). Fatmax is also highly variable on the type of exercise done. For example, treadmill tests yield both a higher rate of fat oxidation at fatmax and a larger range of fatmax than cycle ergometer tests (Zakrzewski and Tolfrey 2010). Most studies concerning fatmax have primarily been involved with weight loss and insulin sensitivity. These studies have yielded some interesting results; standard aerobic training 7 was shown to be better for lowering blood lipid content and BP, while lipid oxidation targeting exercise had higher fat loss and glucose control in diabetics (Romain et al. 2012). However, fatmax is also a valuable tool for studying metabolic diseases effecting fat oxidation. For example, because a fatmax remains constant for an individual wherein training status does not change, protocols targeting fat utilization over long-term studies may only require one fatmax measurement. Researchers can use fatmax to target specific energy sources and study their effect on exercise tolerance and disease symptomology. Exercise Testing in Metabolic Disorders Exercise testing of metabolic disorders can be difficult depending on the type and severity of the disease; if enough energy cannot be recruited to complete a task, or if intermediate metabolic compounds build up to toxic levels, it can become very uncomfortable or even dangerous for the patient to continue the exercise. In spite of this, there does exists some literature on the effects of exercise testing on individuals with metabolic myopathies, or MMs. MM studies have found that because of the difficulties in completing oxidative phosphorylation, most patients will have a reduced VO2 per increase in ventilation (VE) than healthy controls (Taivassalo et al. 2003) (Jeppeson et al. 2012) (Volpi et al. 2011). However, the relationship between workload and VO2 is difficult to analyze, as there is a normal relationship in MMs between VO2peak and cycling workload peak (Wpeak), but not between cardiac output and VO2 (Taivassalo et al. 2003). However, MMs consistently reached a lower Wpeak, corresponding with a reduced VO2peak. Tiavassalo et al. concluded that this meant that the difference in workload 8 capacity between patients and controls could be derived from a limited respiratory function versus limited oxygen availability (Taivassalo et al. 2003). In the case of exercise testing specifically for long-chain FAO disorders, which is what our research is primarily concerned with, Orngreen et al. found that VLCADD patients could not increase their levels of fat utilization above baseline, but could utilize glucose at rates similar to healthy controls, resulting in a quick transition to glucose usage and a consistently higher RER in patients at rest and during exercise (Orngreen et al. 2004). This study suggested that feedback regulation caused by acylcarnitine intermediate build-up inhibited β-oxidation. MCT supplementation has helped to buffer the difference between patients’ and controls’ exercising RERs, in some cases (Behrend et al. 2012). Because this shift is not seen in controls given the same supplemental treatment, it is thought that MCT supplementation provides an alternative source of fat oxidation, potentially prolonging the period of exercise over which fat can be utilized. Unfortunately, the fatmax/lipoxmax targeting concept has not been widely applied into the field of exercise testing in diseases of lipid metabolism. Our particular study is the first to do so in a VLCADD patient population. Not only is this information valuable in assessing the exercise dynamics of patients compared to healthy controls, it also provides information on a range of intensities under which the patient can safely exercise for short periods of time, while maximizing fat oxidation. Given that most patients who experience exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis do so over longer durations of exercise, fatmax targeting provides a research tool under which differences in fat oxidation between patients and controls can be studied safely. The potential to identify points of difference in exercise metabolism is thus enhanced, opening up new possibilities for the development of training programs and disease therapies. 9 Bibliography: Achten J, Gleeson M, Jeukendrup AE. Determination of the exercise intensity that elicits maximal fat oxidation. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise.2002; 34: 92-97. Autti-Rämö I, Mäkelä M, Sintonen H, Koskinen H, Laajalahti L, Halila R, Kääriäinen H, Lapatto R, Näntö-Salonen K, Pulkki K, Renlund M, Salo M, Tyni T. Expanding screening for rare metabolic disease in the newborn: An analysis of costs, effect and ethical consequences for decision-making in Finland. Acta Paediatrica. 2005; 94: 1126-1136. Baruteau J, Sachs P, Broué P, Brivet M, Abdoul H, Vianey-Saban C, de Baulny HO. Clinical and biological features at diagnosis in mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation defects: a French pediatric study of 187 patients. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 2012. Behrend AM, harding CO, Shoemaker JD, Matern D, Sahn DJ, Elliot DL, Gillingham MB. Substrate oxidation and cardiac performance during exercise in disorders of long chain fatty acid oxidation.Molecular Genetic and Metabolism.2012; 105: 110-115. Berardo A, DiMauro S, Hirano M. A diagnostic Algorithm for Metabolic Myopathies. CurrNeurolNeurosci Rep. 2012; 10: 118-126. Bonnet D, Martin D, De Lonlay P, Villain E, Jouvet P, Rabier D, Brivet M, Saudubray JM. Arrhythmias and conduction defects as presenting symptoms of fatty acid oxidation disorders in children. Circulation. 1999;100:2248–2253. 10 Chenevière X, Borrani F, Sangsue D, Gojanovic B, Malatesta D. Gender differences in wholebody fat oxidation kinetics during exercise. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011; 36 (1): 8895. Chenevière X, Malatesta D, Gojanovic B, Borrani F. Differences in whole-body fat oxidation kinetics between cycling and running.Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010; 109 (6): 1037-1045. Gillingham M, Calcar SV, Ney D, Wolff J, Harding C. Dietary management of long-chain 3hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency (LCHADD). A case report and survey. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 1999; 22 (2): 123-131. Grosse SD, Khoury MJ, Greene CL, Crider KS, Pollitt RJ. The epidemiology of medium chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency: An update. Genetics in Medicine. 2006; 8: 205-212. Jeppesen TD, Vissing J, González-Alonso J. Influence of erythrocyte oxygenation and intravascular ATP on resting and exercise skeletal muscle blood flow in humans with mitochondrial myopathy. Mitochondrion.2012; 12: 414-422. Jeukendrup AE, Wallis GA. Measurement of Substrate Oxidation During Exercise by Means of Gas Exchange Measurements. Int J Sports Med. 2005; 26: S28-S37. Jeukendrup, AE and Achten, J. Fatmax: A new Concept to optimize Fat Oxidation During Exercise?. European Journal of Sport Science. 2001; 1 (5): 1-5. Leslie ND, Tinkle BT, Strauss AW, Shooner K, Zhang K, Very Long-Chain Acyl-Coenzyme A Dehydrogenase Deficiency. GeneReviews. 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK68 16/. 11 Martìnez G, Jimènez-Sànchez G, Divry P, Vianey-Saban C, Ruidor E, Rodès M, Briones P, Ribes A. Plasma free fatty acids in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation defects. ClinicaChimicaActa. 1997; 267: 143-154. Medscape Reference: Drugs, Diseases, & Procedures. 2012. http://reference.medscape.com/ Milani RV, Lavie CJ, Mehra MR, Ventura HO. Understanding the Basics of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006; 81 (12): 1603-1611. Moczulski D, Majak I, Mamczur D. An Overview of β-Oxidation Disorders. PostepyMig Med Dosw. 2009; 63: 266-277. Moczulski D, Majak I, Mamczur D. An Overview of β-Oxidation Disorders. Postepy Mig Med Dosw. 2009; 63: 266-277. Orngreen MC, Norgaard MG, Sacchetti M, van Engelen BGM, Vissing J. Fuel Utilization in Patients with Very Long-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Ann Neurol. 2004; 56: 279-282. Péronnet F, Massicotte D. Table of nonprotein respiratory quotient: An update. Can J Sport Sci. 1991; 16: 23-29. Quinlivan R, Jungbluth H. Myopathic causes of exercise intolerance with rhabdomyolysis. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2012; 54:886-891. Rinaldo P, Matern D, Bennett MJ. Fatty Acid Oxidation Disorders. Annual Review of Physiology. 2002; 64: 477-502. 12 Roe DS, Vianey-Saban C, Sharma S, Zabot MT, Roe CR. Oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids by human fibroblasts with very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency: aspects of substrate specificity and correlation with clinical phenotype. ClinicaChimicaActa. 2001; 312: 55-67. Romain AJ, Carayol M, Desplan M, Fedou C, Ninot G, Mercier J, Avignon A, Brun JF. Physical Activity Targeted at Maximal Lipid Oxidation: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism. 2012: 1-11. Schatz UA, Ensenauer R. the clinical manifestation of MCAD deficiency: challenges towards adulthood in the screened population. 2010; 33 (5): 513-520. Spiekerboetter U, Lindner M, Santer R, Grotzke M, Baumgartner MR, Boehles H, Das A, Haase C, Hennermann JB, karall D, de Klerk H, Knerr I, Kock HG, Plecko B, Roschinger W, Schwab KO, Scheible D, Wijburg FA, Zschocke J, Mayatepek E, Wendel U. Management and outcome in 75 individuals with long-chain fatty acid oxidation defects: results from a workshop. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009; 32: 488-497. Spiekerkoetter U, Sun B, Zytkovicz T, Wanders R, Strauss AW, Wendel U. MS/MS-based newborn and family screening detects asymptomatic patients with very-long-chain acylCoA dehydrogenase deficiency. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2003; 143 (3): 335-342. Strauss AW, Powell CK, Hale DE, Anderson MM, Ahuja A, Brackett JC, Sims HF. Molecular basis of human mitochondrial very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency causing cardiomyopathy and sudden death in childhood. Procedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1995; 92 (23): 10496-10500. 13 Sykut-Cegielska J, Gradowska W, Piekutowska-Abramczuk D, Andresen BS, Olsen RKJ, Oltarzewski M, Pronicki M, Pajdowski M, Bogda’nska A, Jabo’nska E, Radomyska B, Ku’smierska K, Krajewska-Walasek M, Gregersen N, Pronicka E. Urgent metabolic service improves survival in long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD) deficiency detected by symptomatic identification and pilot newborn screening. Journal of Inherited Disease. 2011; 34: 185-189. Taivassalo T, Jensen TD, Kennaway N, DiMauro S, Vissing J, Haller RG. The spectrum of exercise tolerance in mitochondrial myopathies: a study of 40 patients. Brain.2003; 126: 413-423. Tolfrey K, Jeukendrup AE, Batterham AM. Group- and individual-level coincidence of the ‘Fatmax’and lactate accumulation in adolescents. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010; 109: 11451153. van Adel BA, Tarnopolsky MA. Metabolic Myopathies: Update 2009. Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease. 2009; 10 (3): 97-121 van Maldegem BT, Wnaders RJA, Wijburg FA. Clinical aspects of short-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 2010; 33 (5): 507511. Volpi L, Ricci G, Orsucci D, Alessi R, Bertolucci F, Piazza S, Simoncini C, Mancuso M, Siciliano G. Metabolic myopathies: functiona; evaluation by different exercise testing approaches. Musculoskelet Surg. 2011; 95: 59-67. 14 Wanders RJA, Ruiter JPN, IJlst L, Waterham HR, Houten SM. The enzymology of mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation and its application to follow-up analysis of positive neonatal screening results. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010; 33: 479-494. Zakrzewski JK, Tolfrey K. Comparison of fat oxidation over a range of intensities during treadmill and cycling exercise in children.Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012; 112: 163-171. 15