File - Ukweli Test Strips - Home

advertisement

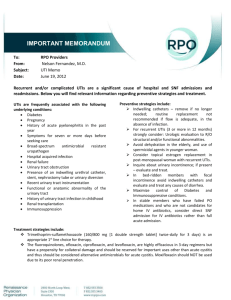

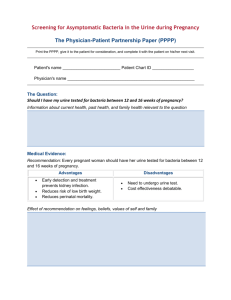

Executive Summary Ukweli Test Strips Kelly Carey, Sarah Krisher, Richard McLaughlin PI: Khanjan Mehta, Director, HESE Program Humanitarian Engineering and Social Entrepreneurship (HESE) Program The Pennsylvania State University Website: http://ukweliteststrips.weebly.com Video Pitch: http://1000pitches.com/pitch/11254 The Problem Urinary Tract Infections are a common worldwide problem affecting nearly one half of women over the course of their lives (Fihn, 2003). They are easily treatable when detected early on. Initial symptoms include painful and frequent urination, nausea and lower back pain localized around the kidneys. Complications from an untreated UTI could lead to kidney damage and, if the woman is pregnant, preterm birth. In some cases, it has been found that bacteria in urine, even without symptoms can result in a pregnancy complication, which is why in Western medicine all pregnant mothers are screened for a UTI multiple times over the course of pregnancy (Uncu Y, 2002). UTIs are a substantial problem in the developing world. In Kenya alone, UTIs account for 39% of all pregnancy complications. It is also understood that due to a lack of education, UTIs often go unreported. According to one study in Panama, the researchers found that the prevalence rate of UTIs was over 20% higher than the number reported by the Panama Ministry of Health (Suzanne L. August, 2012). This mainly occurs because (1) the price of treatment and diagnosis of UTIs are high, (2) lack of appropriate education surrounding UTIs results in people not seeking out the treatment that they need and (3) that women (who are sizably more at risk of contracting a UTI than are men) are uncomfortable going to a male doctor. The Solution Our venture aims to combat the problem of under reporting of UTIs from by reducing costs and investing in educating the local populace. To reduce the cost of diagnosing a UTI, we are improving the technology that uses a commonly available drop-on-demand piezoelectric inkjet printer to produce diagnostic test strips. Three chemical tests will be dipped into a sterile container of the patient’s urine. If a UTI is present all three chemicals will change color. The chemicals are: neutral red, which tests for abnormal pH, Iron (II) sulfate, which changes color in the presence of an Escherichia coli catalase enzyme, and the third and final test that we use is Potassium Chromate which will change color if there are nitrites present in urine. Nitrites are not normally found in human urine however the bacteria convert nitrates, which are normally found in urine, into nitrites. Current test strips are expensive for a number of reasons. The first reason is that they have to be imported from foreign countries. The second reason is that they are designed to test for other conditions in addition to UTIs (such as hernias, preeclampsia, etc.). In addition to cutting costs, our test improves upon the urine dipstick tests already in the market. Conventional urine dipstick tests test for the presence of leukocytes in urine which has a high false positive rate (Hurlbut TA, 1991). By using screening for the E. coli catalase enzyme instead, our strips provide a more accurate diagnosis. Customer Segments and Business Model The primary customer segments will be hospitals, clinics and community health workers. This will be the optimal solution because health workers and hospitals and clinics will already have the qualifications necessary to test the patient’s urine. Our strips will be sold at a lower cost than current urinary test strips and will be more accurate. Strips will be produced at the Children and Youth Empowerment Center, which will store the chemicals needed to diagnose the UTI and produce the strip. We will rent out their underutilized lab space for a fee, and an individual trained for proper handling of chemicals will produce the strips. The first customers will be the Community Health Workers (CHWs) employed by Mashavu (Mashavu Health Workers, MHWs). They will be educated about UTIs, and this will include the risk that UTIs pose to primarily pregnant mothers as well as the proper procedure to test for the presence of a UTI. During the first year, we will market the strips to Nyeri County in central Kenya. The individual who produces the strips will also be responsible for delivering them to our customers. Within the first 3 years, we intend to more individuals to deliever the strips, and they will expand to selling the strips in the surrounding regions. For startup costs in the first year, we will need $2500. We have already one $1000 from the 1000 Pitches Competition, but without the remaining $1500 we are projected to lose money for the first year. This is because initial startup costs, such as attaining approval from the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS), purchasing the computer and printer, the chemicals, rental costs, and salaries. Once the venture is up and running, the revenue generated from selling the strips will be enough to cover the costs of supplies and worker salaries after the first year that the venture is up and running. Implementation Strategy The success of our venture will be evaluated by a number of different factors. At the surface level, enough strips must be sold to increase our revenues for our venture as well as the revenue for our customers. It is also important that more UTIs are reported, because that way we know that people are adequately pursuing proper diagnosis and the treatment that is necessary. Ultimately, we would like to see a decline in pregnancy complications. However, because the causes of pregnancy complications are multi-facetted, numbers of pregnancy complications can increase or decrease due to a number of factors and therefore it may or may not be due to the success of our venture. The technology will be optimized over the course of the spring semester. With the working prototype, further efforts are required to ensure that the strip can be scaled up efficiently and accurately. In addition, we will need to gain the approval to sell these strips from the Kenyan government. We will primarily work with the Kenyan Industrial Research and Development Institute as well as the Kenya Ministry of Health for adequate testing of our product so that it can meet the quality standards from the Kenyan Bureau of Standards. Once these obstacles are overcome and our product obtains the necessary verifications, we plan to implement our venture in Kenya in May of 2014. Contact Information Kelly Carey, BS, Biomedical Engineering, kacarey10@gmail.com Sarah Krisher, BS, Biomedical Engineering, syk5278@gmail.com Richard McLaughlin, BS, Biological Engineering, rdm5186@psu.edu Prof. Khanjan Mehta, Director, HESE Program, khanjan@engr.psu.edu References Fihn, S. D., 2003. Acute Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infection in Women. The New England Journal of Medicine, pp. 259-66. Hurlbut TA, L. B., 1991. The diagnostic accuracy of rapid dipstick tests to predict urinary tract infection.. American Journal of Clinical Pathology, 96(5), pp. 582-58. Suzanne L. August, M. J. D. R., 2012. Evaluation of the Prevalence of Urinary Tract Infection in Rural Panamanian Women. PLOS ONE, 7(10), pp. 1-5. Uncu Y, U. G. E. A. B. N., 2002. Should asymptomatic bacteriuria be screened in pregnancy?. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol, 29(2), pp. 281-5.