Alex Monahan Professor Durham ANTHRO10SC/HUMBIO17SC

advertisement

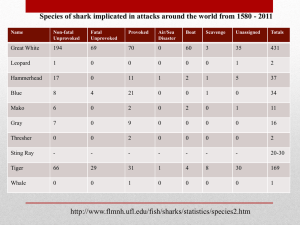

Alex Monahan Professor Durham ANTHRO10SC/HUMBIO17SC Course Paper Shark Finning in the Galápagos: The Unsolvable Problem? Introduction The Galápagos Islands are full of diversity. Unsurprisingly, the Galápagos Marine Reserve (GMR) contains numerous species of sharks, including schools of hammerhead sharks, white-tipped reef sharks, blue sharks, Galápagos sharks, and even whale sharks (Schiller et al. 2013: 9). In the Galápagos ecosystem, sharks are apex predators (Schiller et al. 2014: 12). Thus, decreasing shark populations leads to population changes in various other species. As seen in the prediction of an ecosystem model from one source, “complete removal of sharks in the Galápagos would result in increases in toothed cetaceans, sea lions, and non-commercial reef predators, and subsequently lead to a decrease in bacalao and other commercially valuable fish species” (Schiller et al. 2014: 12). Sharks are crucial to the ecosystem functioning of the GMR. Unfortunately, sharks are vulnerable to overfishing due to slow growth rates and their late age of sexual maturity. Unlike fish, sharks do not produce many offspring. (Dell’Apa et al. 2014: 154) Unsustainable levels of human shark finning in the GMR, consequently, can have devastating impacts on both shark populations and the ecosystem as a whole. Sharks in the Galápagos and around the world are under attack from various forms of illegal fishing. In the Galápagos, shark finning is quite common. In the GMR, shark finning is an illegal, yet highly profitable, practice involving the removal of the various fins of the organism. Then, after the fins of the organism are cut off, the rest of the shark is typically thrown back into the ocean. Without their fins, sharks cannot swim or breathe properly. These sharks usually sink to the bottom of the ocean and die. Because shark finning only exploits the fins of the organism, just 5-16% of a shark’s body weight is kept by fishermen, helping to create an unsustainable practice. (Dell’Apa et al. 2014: 154) According to one study, out of the forty shark species found in Ecuadorian waters, 30 are frequently caught by fishermen (Carr et al. 2013: 317). Additionally, according to this same study, “All of the most commonly caught species are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, a comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biological species, and are considered as Near Threatened or Vulnerable” (Carr et al. 2013: 318). Thus, conservationists must work to preserve numerous shark species being exploited by fishermen in the GMR. Although data on shark finning is relatively scarce, Figure 1 of the Appendix shows the onboard catch data for an illegal shark finning ship caught within the GMR. As seen in this figure, various shark species are exploited by fishermen (from blue sharks to the Galápagos shark), forming a complex conservation problem. Additionally, as seen in this same figure, illegal fishermen target sharks at a variety of locations in the GMR, from Isabela Island to Wolf Island to Darwin Island. Thus, enforcement of anti-finning regulation is often difficult, as enforcement mechanisms must span a large area to successfully combat illegal finning in the GMR. Shark finning is profitable due to the high cost of shark fins in East Asian markets, especially China and Hong Kong (Fabinyi 2012: 83). As stated in one study, “Imports of shark fin into Hong Kong, the world’s most important trade centre for this product, rose by 123.2% between 1980 and 1995” (Smith et al. 1998: 663). This high demand for shark fins led to an eventual increase in shark fin output by illegal fishing, as seen in Figure 2 of the Appendix. Additionally, as described in another study, Chinese households increased their expenditures on “aquatic products” from one percent to four percent between 1990 and 2007, helping to explain increased demand for shark fins (Fabinyi 2012: 85). The famed shark fin soup can sell for up to $160 per bowl, depending on the amount of shark and the specific species of shark used in the dish (Dell’Apa et al. 2014: 156). Clearly, illegal shark finning is a multilayered issue with deep cultural ties that has proven difficult to solve. However, solutions to illegal shark finning must be found to preserve both the shark species in the GMR and the ecosystem as a whole. In past years, what methods have been effective in reducing illegal shark finning? The purpose of this paper was to examine the most effective methods of reducing shark finning in the GMR. My first hypothesis was that cultural campaigns have been effective in decreasing shark finning. My second hypothesis was that policy shifts have been effective in decreasing past shark finning in the GMR. On a related note, my third hypothesis proposed economic growth in Hong Kong and China led to an increase in shark finning in the GMR. Hypothesis 1: Cultural Campaigns My first hypothesis was that cultural campaigns have been effective in decreasing shark finning. These anti-finning campaigns mainly occur in China and Hong Kong, as these areas have the highest demands for shark fin soup. Campaigns include anti-finning movements, educational programs, awareness mechanisms, etc. As described in one study, “gaining a better understanding of different aspects of Chinese seafood consumption will be of considerable importance for efforts to sustain the marine resources that feed this market” (Fabinyi 2012: 84). According to another study, shifting cultural values is vital when preserving biodiversity, such as in the fight against illegal shark finning (Ruckelshaus et al. 2013: 11). Although these past two claims are broad, both studies highlight an important point - culture is vital to consider when discussing economic markets and sources of demand. Anti-finning campaigns are effective because they lead to a decrease in the demand for shark fins. A shift in demand leads to a lower equilibrium price and a lower equilibrium quantity of shark fins in economic markets, as seen in Figure 3. In other words, in theory, a decrease in demand for shark fins leads to less sharks being killed. Additionally, as demand for shark fins decreases, fishermen have less of an incentive to remain in the illegal shark finning business due to the lower price of shark fins in these economic markets. According to the literature, targeted cultural campaigns appear to have been highly successful in combatting shark finning in China and Hong Kong. One example of a targeted campaign against shark finning was run by the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. When, in Hong Kong, a Disney theme park began to serve shark fin soup, this non-profit began to release high-impact, anti-finning images aimed at children. (Dell’Apa et al. 2014: 156) According to this source, “In accordance to the PR, part of the success of this campaign lay in the use of a highimpact visual strategy of persuasive communication, consisting in campaign’s materials, such as t-shirts and stickers, depicting a grinning Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse intent in slicing fins from bleeding sharks” (156). The soup was subsequently removed from the menu. In another example of a specific, high-profile campaign against shark finning, professional basketball player Yao Ming, a celebrity in China, was used in a variety of ad campaigns, banners, and commercials in an attempt to reduce finning, as seen in Figure 4. According to one study, these campaigns were extremely successful in raising awareness and even in reducing consumption of shark fin soup. As seen in the text, “A survey conducted by WildAid in the run-up to the Beijing Olympics found that their media campaigns with Yao Ming were having an impact, claiming that of those who had seen the campaign, 83% had stopped or reduced consumption” (Fabinyi 2012: 86). This statistic highlights the potential of anti-finning campaigns in future years. According to another source, the human dimension of finning cannot be underestimated. Successful education programs and campaigns, thus, are crucial when combatting shark finning. According to this source, shark finning began in China during the Sung Dynasty, approximately a thousand years ago. (Dell’Apa et al. 2014: 155) “The risk involved in catching sharks served as a tribute to the emperor” and the “consumption of strong or fierce animals, such as sharks, was believed to give strength, and thus was considered suitable for the imperial family” (Dell’Apa et al. 2014: 155). Thus, shark finning has deep cultural connections to China. According to Dell’Apa, many Chinese still believe shark fins give tonic benefits, and, often times, people are considered cheap or poor if they do not serve this soup at important functions, including corporate events and weddings (156). This article concludes by noting that for a campaign targeting reduced consumption of shark fin soup, “a positive attitude change would result in practices to protect sharks from illegal shark finning activities, plus swaying from consuming shark fin soup” (158). Hypothesis 2: Policy Shifts The second hypothesis was that policy shifts have been effective in reducing shark finning in the GMR. Policy shifts, unlike cultural campaigns, cause decreases in supply, as seen in Figure 5 of the Appendix. Similar to decreases in demand, decreases in supply reduce the equilibrium quantity of shark fins sold (e.g. less sharks are killed). However, unlike decreases in demand, decreases in supply lead to a higher equilibrium price, as seen in Figure 5. In other words, as the supply of shark fins becomes more and more restricted, illegal fishermen will receive higher and higher prices for their catches. Enforcement mechanisms, thus, must be strong for policies banning or restricting shark finning. Unfortunately, enforcement of shark finning regulations is not always strong in the GMR. According to one book, “district judges refuse to comprehend the gravity of environmental crimes, and they sympathize with fishers” and “ridiculously low fines are applied” (De Roy 2009: 219). This claim is echoed in another study. This study states that government and policy failures have allowed shark finning to continue to this day (Schiller et al. 2013: 20). Consequently, moving forward, if policy shifts are expected to be effective in the GMR, enforcement mechanisms must strengthen. As described in another research article, “illegal shark fishing is an ongoing concern” and “stricter enforcement and legislation is urgently needed, particularly in areas of high biodiversity” (Carr et al. 2013: 317). Without strong, strict enforcement, policy shifts will be of little impact in the GMR. Poaching is a practice similar to shark finning, as this practice is illegal and impacts threatened or endangered species. Thus, the success of policies relating to poaching is highly relevant when creating policies combatting shark finning. In one study on poaching completed in 2009, researchers Lemieux & Clark analyzed elephant population data after the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), a convention that reached an agreement to ban the ivory trade among Member States of the United Nations. According to this study, “an analysis of elephant population data from 1979 to 2007 found that some of the 37 countries in Africa with elephants continued to lose substantial numbers of them. This pattern is largely explained by the presence of unregulated domestic ivory markets in and near countries with declines in elephant populations” (Lemieux & Clark 2009: 451). These results from Lemieux & Clark are similar to another study completed by Dell’Apa. Unlike the study from Lemieux & Clark, however, the Dell’Apa study specifically focuses on the success of shark finning regulations. According to the Dell’Apa source, after bans on shark finning were put into place in the European Union and the United States, researchers discovered that “although shark fin imports to Hong Kong dropped after the adoption of these bans, the overall effect of finning regulations on shark fin trade was less clear” and “shark finning regulations may have fuelled black-market so that actual trade volumes were misrepresented” (Dell’Apa et al. 2014: 157). In other words, limits or bans on finning often times just move money to the illegal black market. The two studies of this paragraph suggest that policy shifts may not even decrease the amount of sharks killed in the GMR. In other words, these two studies suggest that my second hypothesis is incorrect. Policies can have loopholes, too. Ecuador, for example, has had loopholes in the countries shark finning policies. Initially, shark fin exports and shark fishing were banned in the country in both 1989 and 2004. However, Ecuador then made an amendment. (Schiller et al. 2014: 12) According to one study, “although this amendment still prohibits shark finning and the dumping of sharks at sea, fishers are now allowed to trade fins extracted from sharks incidentally caught during fishery activities under a special permit” (Schiller et al. 2014: 12). This loophole allowed fishermen to trade fins without punishment, forwarding shark finning in Ecuador and the GMR (Schiller et al. 2014: 12). Clearly, if policies expect to decrease finning in the GMR, then these policies must be properly and carefully designed without loopholes. After an analysis of the literature on this subject, in the past, policy shifts seem to have been relatively ineffective when combatting shark finning in the GMR. Unless policies are carefully designed and very well-enforced, we should not expect government regulation to significantly reduce finning. Consequently, I believe cultural campaigns, which aim to decrease the demand for shark fins, will be most effective when moving forward in the fight against illegal shark finning in the GMR and around the world. Hypothesis 3 My third hypothesis was that economic growth in China led to an increase in illegal shark finning in the GMR. As seen in Figure 6 of the Appendix, imports of shark fins to China and Hong Kong increased from 1992 to 2004. According to one study, “more than 90 % of shark fin imports reported to the FAO in 2004 were to Hong Kong (58 %) and China (36 %), where the fins are used as the main ingredient of a traditional soup” (Dell’Apa et al. 2014: 154). According to this same study, the growth of the Chinese economy and middle class have led to an increased demand for shark fins (155). Another study echoes the research of Dell’Apa. This study notes that the “main incentive for shark fishing and finning in the last decade has been the demand from mainly East Asian markets, and Hong Kong in particular” (Schiller et al. 2014: 12). Thus, the literature supports my third hypothesis. Economic growth in China and Hong Kong have fueled the illegal black market for shark fins. Conclusion This paper supports the first hypothesis that cultural campaigns have been effective in reducing shark finning in the GMR. On the contrary, this paper does not support the second hypothesis that policy shifts have been effective in reducing shark finning in the GMR. Consequently, more anti-finning, cultural campaigns should be aimed at East Asian markets, mainly China and Hong Kong. Anti-finning commercials and advertisements with celebrities from these areas (e.g. Yao Ming, Jeremy Lin) should be utilized more frequently, aimed at decreasing demand for shark fin soup. Once demand in East Asian markets decreases enough to make finning a poor, unattractive source of income for fishermen, these people will turn to other job markets. On the other hand, unless policies are carefully constructed and have strict enforcement, bans and regulations on shark finning will have little impact, as money will simply flow out of the legal market and into the illegal black market. In one study, researchers recommended “incentive-based nature protection policies” to address biodiversity issues (Dörschner & Musshoff 2015: 90). Although this recommendation is broad, the implications are clear - incentives must be aligned properly when addressing shark finning with policy action. Fishermen cannot be rewarded for their illegal activities. Additionally, in upcoming years, more alternatives to illegal shark finning should be given to the fishermen of the GMR. As stated by one past shark finner, “When I looked into the eye of the shark and realized how special it was, I felt I had committed the worst crime in history” (Bassett 2009: 229). These fishermen often times care for the animals of the GMR, yet, with limited legal job options, many fishermen feel as if illegal activities are their only options. Alternatives for these fishermen must be found. Shark ecotourism is an example of a profitable, legal alternative for these fishermen (Dell’Apa et al. 2014: 161). In addition to providing an innovative method of making a living, shark ecotourism incentivizes fishermen to conserve shark populations, as thriving shark populations become an integral part of their business. References Bassett, C. A. (2009). Galápagos at the crossroads: Pirates, biologists, tourists, and creationists battle for Darwin's cradle of evolution. National Geographic Books. Carr, L. A., Stier, A. C., Fietz, K., Montero, I., Gallagher, A. J., & Bruno, J. F. (2013). Illegal shark fishing in the Galápagos Marine Reserve. Marine Policy, 39, 317-321. Clarke, S., Milner-Gulland, E. J., & Bjørndal, T. (2007). Social, economic, and regulatory drivers of the shark fin trade. Marine Resource Economics, 305-327. De Roy, T. (Ed.). (2009). Galápagos: preserving Darwin's legacy. Firefly Books Limited. Dell’Apa, A., Smith, M. C., & Kaneshiro-Pineiro, M. Y. (2014). The influence of culture on the international management of shark finning. Environmental management, 54(2), 151-161. Dörschner, T., & Musshoff, O. (2015). How do incentive-based environmental policies affect environment protection initiatives of farmers? An experimental economic analysis using the example of species richness. Ecological Economics, 114, 90-103. Fabinyi, M. (2012). Historical, cultural and social perspectives on luxury seafood consumption in China. Environmental Conservation, 39(01), 83-92. Lemieux, A. M., & Clarke, R. V. (2009). The international ban on ivory sales and its effects on elephant poaching in Africa. British Journal of Criminology, 49(4), 451-471. Ruckelshaus, M., McKenzie, E., Tallis, H., Guerry, A., Daily, G., Kareiva, P., ... & Bernhardt, J. (2013). Notes from the field: lessons learned from using ecosystem service approaches to inform real-world decisions. Ecological Economics. Schiller, L., Alava, J. J., Grove, J., Reck, G., & Pauly, D. (2013). A reconstruction of fisheries catches for the Galápagos Islands 1950-2010 Schiller et al 2013. Schiller, L., Alava, J. J., Grove, J., Reck, G., & Pauly, D. (2014). The demise of Darwin's fishes: evidence of fishing down and illegal shark finning in the Galápagos Islands. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. Smith, S. E., Au, D. W., & Show, C. (1998). Intrinsic rebound potentials of 26 species of Pacific sharks. Marine and Freshwater Research, 49(7), 663-678. Appendix Figure 1: (Carr et al. 2013: 319) Figure 2: United States Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Figure 3: johanneds.wordpress.com Figure 4: www.bluespheremedia.com Figure 5: www.raybromley.com Figure 6: (Clarke et al. 2007: 310)