Checkpoint Contents

Estate Planning Library

Estate Planning Journals

Estate Planning Journal (WG&L)

Estate Planning Journal

2014

Volume 41, Number 07, July 2014

Articles

Factor Premarital Agreements and Divorce Into Estate Plans, Estate Planning Journal

PREMARITAL AGREEMENTS

Factor Premarital Agreements and Divorce Into Estate Plans

While the precise requirements for an enforceable premarital agreement depend on state

law, financial disclosure is generally crucial.

Author: LINDA J. RAVDIN, ATTORNEY

LINDA J. RAVDIN is a partner in the Bethesda, Maryland, law firm of Pasternak &

Fidis, P.C., where she practices family law exclusively. She is a member of the

Maryland, Virginia, and District of Columbia Bars. She is the author of Premarital

Agreements: Drafting and Negotiation (ABA, 2011) and TM849-2d Marital

Agreements (Tax Mgmt. Inc., 2012).

With the increasing acceptance of premarital agreements, including among young, first-timers; the addition

of same-sex couples to the marriage pool; and the continued high rate of divorce, more premarital

agreements are figuring in divorce litigation. This article addresses some of the special concerns that arise

in the divorce scenario that attorneys should consider when drafting documents.

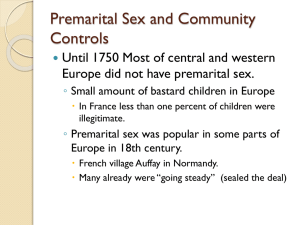

Validity at divorce: process vs. substance

As of 2014, 26 states and the District of Columbia have adopted the Uniform Premarital Agreement Act

(UPAA), and some other states follow validity criteria similar to those of the UPAA (see Exhibit 1). In these

states, the emphasis is on process, not fairness of the terms. Under UPAA §6(a), a premarital agreement is

valid if the parties executed it voluntarily. Furthermore, if the agreement was unconscionable at execution,

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

the challenging party must have received "fair and reasonable" financial disclosure, had constructive

knowledge of the other party's property and financial obligations, or waived disclosure.

Exhibit 1. UPPA Validity Criteria Followed in These Jurisdictions

The 20 jurisdictions that adopted the UPAA without changing the validity criteria are:

(1) Arizona.

(2) Delaware.

(3) District of Columbia.

(4) Florida.

(5) Hawaii.

(6) Idaho.

(7) Illinois.

(8) Kansas.

(9) Maine.

(10) Montana.

(11) Nebraska.

(12) Nevada.

(13) New Mexico.

(14) North Carolina.

(15) Oregon.

(16) Rhode Island.

(17) South Dakota.

(18) Texas.

(19) Utah.

(20) Virginia.

*****

The UPAA permits a court to uphold an agreement that was unconscionable when executed as long as one

of the financial disclosure requirements was met. Other states preclude enforcement of an agreement that

was unconscionable at execution. However, the primary emphasis, even in these states, is on the fairness

of the process. Courts hold that competent adults are free to enter into a premarital agreement that is

substantively unfair. A court will not relieve a party of a bad bargain.

1

Validity in the second-look states

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

In a significant minority of states, a court may consider the substantive fairness of a premarital agreement

as of divorce-known as the "second look." These states are Connecticut, New Jersey, and North Dakota

(UPAA states), and Alaska, Georgia, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, New

Hampshire, South Carolina, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wisconsin (non-UPAA states). By contrast, little

authority would permit a probate court to take a second look after death.

Courts in second-look states judge the adequacy of the substantive terms by one of two standards:

(1) Mere unfairness. 2

(2) Unconscionability. 3

The degree of unfairness required to prove unconscionability is quite extreme. Challenging parties have an

uphill battle; nevertheless some challengers do prevail. Events subsequent to marriage can affect the

validity of an agreement governed by the law of a second-look state. The stronger party and counsel should

consider the fairness of the terms of the agreement at the outset and whether it may become unfair over

time. Driving too hard a bargain may prove to be the stronger party's undoing.

4

Most challenges to validity fail

Most challenges to validity fail. This is true even in the second-look states. But spouses dissatisfied with

their premarital agreements continue to try. The reporters are full of cases in which a party challenged a

premarital agreement on the ground of duress or lack of voluntariness. The most common factors asserted

in support of a duress claim are:

•

Late presentation of the agreement.

•

A threat not to marry unless the agreement was signed.

•

Lack of legal advice.

•

Emotional distress.

•

Disparity of bargaining positions.

Courts have generally held that a single factor-such as late presentation or lack of legal advice-is

insufficient standing alone. 5 This is good news for proponents. However, in many of these cases, the

proponent would have been better served by a fairer process and substantive terms that afforded an

economically disadvantaged spouse some degree of financial security. Insofar as the Uniform Premarital

and Marital Agreements Act (UPMAA) is adopted, it will mandate a fairer process.

The rare winner

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

In the rare cases where a court has invalidated a premarital agreement on duress grounds, there has

generally been a combination of coercive factors that led to the result, often including inadequate financial

disclosure. Holler v. Holler, 6 a South Carolina case, provides a good example of how extreme the

procedural unfairness has to be to get a premarital agreement invalidated in most states.

The wife in this case was an uneducated Ukrainian national. Shortly after arriving in the U.S. she became

pregnant with the husband's child. She was completely dependent on the husband and had no money to

hire counsel. Her visa was due to expire. The husband did not have the agreement translated. She signed

the agreement six days before the wedding. The court found both duress and that the agreement was

unconscionable at execution.

Financial disclosure

In both the divorce and the death scenarios, a proponent's fair and accurate financial disclosure can be the

key to prevailing in a challenge. A written, itemized statement of major assets with reasonable valuations,

debts, and amounts and sources of income is the ideal. 7 The reporters are full of cases where a proponent

provided something less than full disclosure, for example, by omitting some assets or not providing values,

or relied on oral disclosure or the opponent's preexisting knowledge. In many of these cases, the proponent

ultimately prevailed, but he or she incurred significant fees and was at risk while the litigation was pending.

When a proponent must prove constructive knowledge, or informal disclosure, he or she will have a

potentially burdensome task. It may be necessary to locate documents not readily available, and find

witnesses who have retired and moved away, or whose memories have faded. A reasonably complete

written statement, annexed to the agreement, including values, will survive the passage of time, loss of

memory, and death of witnesses.

UPMAA: best practices

Most clients planning for a premarital agreement seek a predictable outcome; they want to know in advance

what their rights and obligations will be if the marriage fails, and that a court will uphold the agreement if

challenged. The best protection a proponent can get from the risk and cost of future divorce litigation is a fair

process and a fair result. The Uniform Law Commission adopted the Uniform Premarital and Marital

Agreements Act (UPMAA) in 2012. To the extent enacted, the UPMAA will raise the process standards for

validity of premarital agreements, but will require little alteration in current best practices. Best practices are

the same, whether the agreement is ultimately enforced at death or divorce.

The most important change the UPMAA will bring about is the requirement of section 9(a)(2) that the

challenging party have access to independent legal advice before signing. Access to counsel means both

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

the money to hire a lawyer and the time to find one, consult with the lawyer, and consider his or her advice.

When there is a significant disparity in resources, the proponent should plan to pay the other party's legal

fees. The access to counsel requirement has a two-fold impact on the fairness of the process from the

standpoint of the economically weaker party. It means the proponent should present the agreement well in

advance of the wedding; and it will give the other party a meaningful opportunity to negotiate the terms.

In addition, in contrast to the UPAA, the UPMAA makes a premarital agreement unenforceable if it was

unconscionable at execution, even if executed voluntarily and with adequate financial disclosure. Actual

substantive fairness of terms is not a requirement for validity. 8 However, a proponent will be better

protected if the agreement provides a reasonable degree of financial security for an economically

disadvantaged party.

Validity at divorce and the migratory couple

Parties may, subject to general choice-of-law principles, select the state whose law will govern any future

dispute about the agreement, including a dispute about whether the agreement is valid. 9 There must be a

nexus between the parties, or one of them, and the state whose law is chosen.

The choice of governing law, or the failure to select governing law, can affect resolution of a future dispute

about validity of the agreement. For example, in DeLorean v. DeLorean, 10 the husband's disclosure was

inadequate and would have doomed the premarital agreement had its validity been determined under New

Jersey law. However, the New Jersey court gave effect to the parties' choice of California law and upheld it

as adequate under California disclosure standards. By contrast, in Rivers v. Rivers, 11 the premarital

agreement, executed in Louisiana, had no choice-of-law provision. The Missouri court applied stricter

Missouri law and held the agreement was invalid at divorce.

Failure to select governing law can also create an opportunity for litigation over what law a court should

apply to resolve a dispute about validity. For example, in Black v. Powers, 12 two Virginia residents traveled

to the Virgin Islands where they signed a premarital agreement with no choice-of-law clause and got

married. The appeal resolved the dispute about applicable law in favor of Virgin Islands law although it

apparently made no difference to the outcome of the dispute about validity. An express choice-of-law

clause could have eliminated one facet of the litigation.

Section 187(2)(b) of the Restatement permits a court to refuse to apply the law chosen by the parties when

it conflicts with a fundamental policy of the forum state. Case law provides little guidance as to when a court

in a substantive fairness state will apply its own law on public policy grounds. A court in a second-look state

could conclude that fairness, or conscionability, at divorce is sufficiently important to warrant application of

the law of the forum state, but there is little case law to guide the practitioner as to when courts will reject the

parties' contractual choice of law. In the absence of guidance, proponents will generally be better served by

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

an agreement that makes reasonable provisions for an economically disadvantaged spouse.

Spousal support waivers

In the majority of states, parties may enter into a contract that completely waives spousal support or that

fixes support at a predetermined amount and duration coupled with a waiver of all other support rights.

Spousal support award over waiver. In the majority of states, a court can make a spousal support award

at divorce over a premarital agreement waiver, albeit under limited circumstances. Under the UPAA, a court

can make an award only to keep a spouse off public assistance.

13

In the 15 second-look states, because

the court can consider whether an agreement remains substantively fair (or, not unconscionable) at divorce,

it can separately consider fairness of the alimony waiver.

14

In another group of states, a divorce judge is

permitted to consider whether to enforce a spousal support waiver under circumstances less severe than

welfare eligibility.

There is some variation among these states as to the degree of post-divorce hardship required to support

an award. Some states, by statute or case law, preclude enforcement of a support waiver that is

unconscionable at divorce. 15 In some states, the claimant must prove changed circumstances. There is

variation among these states about whether the change must have been unforeseeable.

Where there is a significant disparity in resources, it will often be better for the agreement to make

provisions for some support. Courts are more likely to enforce a waiver when it is coupled with even modest

support for an economically disadvantaged spouse.

No-waiver states. In New Mexico, Iowa, South Dakota, and Mississippi, a spousal support waiver in a

premarital agreement is not enforceable. In these states, the divorce judge has the same authority to

consider a claim for spousal support as in the absence of an agreement.

Waiver of temporary (pendente lite) spousal support. A spouse may seek an award of temporary

support, i.e., support payable while a suit for divorce is pending and the parties remain married. Courts in a

few states have ruled that the right to support during marriage is not waivable. As a result, a court in these

states could make a temporary award, despite a waiver, if otherwise appropriate. Most courts have not yet

ruled on enforceability of a waiver of temporary support. This is an area of uncertainty for future payors.

Spousal support waiver and the migratory couple. The forum for divorce may be a different state than

that of the state whose law the agreement provides will govern it. The law and public policy of the forum

state may override the parties' contractual choice of law and permit the court to impose a support obligation

different from that to which the parties agreed. 16 As is the case with challenges to general validity,

discussed above, there is little guidance in the case law. It is reasonable to assume courts in no-waiver

states will refuse enforcement on public policy grounds.

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

Waiver of right to support during marriage; medical expenses and other necessaries. Many states

have a statutory or common law spousal necessaries rule. A necessaries rule obligates spouses to support

each other during the marriage generally, or may limit the obligation to medical necessaries. Such an

obligation may survive divorce and may not be waivable as in many cases it creates a cause of action in

favor of a third-party provider. 17

Enforceability of support waiver with respect to resident alien spouse. When the support claimant is a

sponsored immigrant, and the spouse is the sponsor, the claimant may be able to obtain some limited

support notwithstanding an otherwise valid waiver in a premarital agreement. A person who petitions for

admission of a spouse or fiancé(e) as a family member will sign Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) Form

I-864 as the sponsor. 18 INA Form I-864 is a contract between the sponsor and both the sponsored

immigrant and the U.S. government under which the sponsor promises to provide support to the immigrant

sufficient to maintain him or her at 125% of the federal poverty line. The sponsor's obligation terminates

when the immigrant becomes a U.S. citizen, completes 40 quarters of covered employment in the Social

Security system, or permanently departs the U.S., or on the death of either party.

19

Divorce does not terminate the sponsor's obligation. The immigrant-spouse is entitled to enforce his or her

right to support despite a contractual waiver. 20 The sponsored immigrant has no obligation under the I-864

to seek or obtain employment to mitigate damages, or to notify the sponsor when one of the termination

events has occurred. 21 The termination events do not include remarriage or cohabitation.

22

Enforceability of spousal support waiver in domestic violence proceeding. A common feature of state

domestic violence statutes is a provision for an award of support as part of the spectrum of relief a court

may afford the victim. 23 A court may determine on public policy grounds that a law of this type supersedes

a contractual waiver of support. There appears to be no reported case where a court ruled on such an

award. A court in a second-look state could make an award if otherwise warranted based on a finding of

changed circumstances or unconscionability. 24 The UPMAA expressly addresses this issue. It provides

that a term in a premarital agreement is unenforceable that "limits or restricts a remedy available to a victim

of domestic violence." 25

Alimony and tax consequences

When a premarital agreement provides for payment of alimony, counsel needs to consider tax

consequences at the drafting stage. Many payors want alimony payments to be deductible. To qualify as

deductible alimony:

(1) The payments must be made in cash.

(2) They must be made under a divorce or separation instrument.

(3) They must terminate on the death of the payee.

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

(4) They cannot be child support.

(5) The parties must file separate tax returns.

26

The Code defines a divorce or separation instrument as: "(A) a decree of divorce or separate maintenance

or a written instrument incident to such a decree, (B) a written separation agreement, or (C) a decree ...

requiring a spouse to make payments for the support or maintenance of the other spouse." 27 A premarital

agreement is not a separation agreement. 28 In order to get the intended tax treatment, the agreement can

provide for one of the following:

•

The payor will be obligated to begin making payments on or after the date the parties sign a separation

agreement, or a party obtains a court decree, to carry out the alimony obligation.

•

Until execution of a separation agreement or entry of a decree, the payor will pay a reduced

nondeductible amount, as determined at that time by his or her CPA.

•

The agreement could predetermine a lower nondeductible amount payable until there is a divorce or

separation instrument, followed by the higher deductible payment.

•

Parties could expressly opt out of alimony treatment entirely.

29

Divorce and child custody

Statutes and case law uniformly preclude parties to a premarital agreement from contracting to divest a

court of authority to make or modify custodial arrangements for a minor child upon separation or divorce.

30

Parties may wish to have the agreement acknowledge their intent that they will have joint legal or shared

physical custody of a child. Such a provision will not bind a court in a future custody dispute.

31

However, it

will generally be severable from provisions regarding property and spousal support; thus, its

unenforceability will not affect the validity of the agreement as a whole.

Some premarital agreements provide for a spouse to retain exclusive rights to an existing residence, or give

one spouse a right to buy out the other's interest in a residence, in the event of a marital separation. The

right to evict a spouse can distort the resolution of custody of a child by giving one spouse an unfair

advantage as it could force a parent out of the home prematurely. A provision for spousal eviction could be

qualified so as to forestall the obligation to move until a court has made a ruling on temporary or permanent

custody.

Financial provisions for children

A contract will not divest a court of authority to order a parent to provide appropriate support for a minor

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

child upon separation or divorce. 32 An agreement that requires less than the law requires will not preclude

the court from ordering a parent to meet his or her threshold obligation. By contrast, parties may enter into

an enforceable agreement that expands the financial rights of a child and the financial obligations of one or

both parties to the child in the event of separation or divorce. Thus, parties may contract to provide for

payment of post-majority periodic support to a custodial parent, to pay for college, or to make provisions for

a child after the death of a parent.

To the extent parties choose to contract beyond the scope of the state-mandated duty of minority support,

their obligations are governed exclusively by the law of contracts.

33

A court will not relieve a payor who

contracts to pay for the benefit of a child an amount that may in retrospect appear to be too generous, that

the party later comes to regret, or that is rendered burdensome by changed circumstances.

Same-sex couples and divorce

In marriage equality states, a same-sex premarital agreement will be governed by the same validity criteria

as that of an opposite-sex couple. Thus, a migratory same-sex couple who live in a marriage equality state

will face the same uncertainties about issues such as enforcement of a spousal support waiver and

application of higher standards for validity or a second look at divorce in a forum state other than that of their

contractual choice of law.

A same-sex couple who separate while living in a nonrecognition state face a host of challenges. These

include a court refusing to enforce the premarital agreement as an otherwise valid contract and the lack of a

forum to dissolve the marriage and obtain necessary orders to divide retirement benefits. The drafting

attorney can anticipate some problems. The following text addresses the problem of consideration for the

contract when a court may deem the marriage alone insufficient:

Waiver of other Rights and Claims. The parties intend and agree that this Agreement,

and any amendment thereto, or supplemental or additional contract or other instrument

they may execute, shall completely define their property and support rights upon death or

dissolution, whether or not their marriage is recognized as valid. They acknowledge that

courts have recognized various legal claims that may arise from a nonmarital

cohabitation relationship upon dissolution or the death of one party, including, but not

limited to, oral contract, business partnership, unjust enrichment, and constructive trust.

They agree and intend to waive all such claims and that their property and support rights

shall be governed only by this Agreement, and any other or additional written agreement,

or other instrument, such as a property deed or title, they may subsequently enter into

with each other.

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

The following text addresses the forum problem:

Consent to Personal Jurisdiction. The parties recognize that if they separate, it is in their

mutual best interests to be able to obtain a divorce from the bond of matrimony with a

minimum of expense and inconvenience. Accordingly, in the event of a separation where

the parties are living in a state whose courts will not grant a divorce, and in the further

event that one party moves to a state or jurisdiction that will grant a divorce, the other

spouse hereby consents to the personal jurisdiction of the courts of such state, subject to

the following:

i. such consent is limited to personal jurisdiction for the sole purpose of granting a divorce

and enforcing the terms of this Agreement;

ii. such consent shall not extend to an adjudication of validity of this Agreement, nor to

enforceability of any provision herein, unless the nonresident spouse expressly consents

to such jurisdiction;

iii. the spouse who is not a resident in the dissolution state shall have no obligation to

appear in person and, accordingly, the parties shall consent to entry of an order

permitting him/her to appear by telephone, video, or other remote means, or by

deposition.

Religious divorce

Parties who for religious reasons may need to obtain an ecclesiastical divorce or annulment in the event the

marriage ends in a civil divorce, may wish to include a provision obligating the other party either to provide

a religious divorce or to appear before a religious tribunal. Courts have generally held that secular

provisions of a religious marriage agreement may be enforced in a civil court.

34

Courts have analogized

such provisions to a contractual provision for arbitration or other form of alternative dispute resolution.

35

Other cases have gone a step further and ordered a husband to comply with an agreement to grant the wife

a religious divorce. 36

Enforceability of contractual waiver of fees in divorce

The "American Rule" holds that each party to a legal dispute must bear his or her own legal fees and costs

of litigation. In the domestic relations arena, however, statutes and appellate decisions have carved out

many exceptions, permitting a judge to order one party to pay some or all of the fees and costs incurred, or

to be incurred, by the other party. Most significantly, in the absence of a valid contractual waiver, a court

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

may be able to order the economically stronger party to advance monies to the weaker party to enable the

weaker party to litigate the validity of the agreement.

A waiver of fees and costs that may be incurred at divorce is generally enforceable under the UPAA and in

the majority of non-UPAA states. Most courts that have ruled on a fee request made by a spouse to

challenge the validity of an agreement have held a contractual fee waiver to control.

37

General validity of a fee waiver does not mean a court can never make a fee award. Some courts have held

that a lawyer's fee waiver is not enforceable if unconscionable at divorce even where the agreement as a

whole is upheld. 38 In a minority of states, courts refuse to enforce fee waivers on the theory that the party

disadvantaged by the premarital agreement should not have to forgo the opportunity to litigate his or her

claim due to lack of funds. 39 In states where judges have more discretion to award spousal support over a

waiver, some courts have held the obligation to pay attorney's fees springs from the spousal support

obligation.

Even when there is no dispute about the validity of a premarital agreement, divorcing parties may incur fees

to resolve a dispute about their obligations or rights under the agreement. Courts in some states have

interpreted their statutory provisions for fee shifting to permit an award to enable a weaker party to litigate

his or her rights, despite a contractual waiver, when there is a significant disparity in resources. 40 Other

courts give effect to a waiver if the agreement is valid as a whole.

41

Some courts have interpreted a fee waiver not to apply to litigation of subjects not governed by the

agreement, such as custody and child support. 42 An Illinois case, Marriage of Best, 43 held that a premarital

agreement waiver of lawyer's fees for litigation of custody and child support violated public policy and was

therefore unenforceable. Similarly, courts have held a contractual fee waiver inapplicable to litigation of

spousal support where such a claim was nonwaivable or had not been waived, and to litigation of a claim for

temporary support or separate maintenance where a waiver of these rights was unenforceable. 44

It will often be in a stronger party's interest to include a waiver of legal fees. A lawyer for a disadvantaged

party should consider including a provision that makes it clear that the waiver does not apply to fees and

costs that may be incurred to determine custody or child support.

Divorce and the incapacitated client

A variety of circumstances could motivate a guardian of an incapacitated adult who has a premarital

agreement to file for divorce. In Tillman v. Tillman, 45 the couple had a premarital agreement that obligated

the husband to provide for the wife's expenses during the marriage. Both husband and wife were

incapacitated and had guardians. The husband was in a nursing home. The wife's guardian petitioned the

court to enforce the husband's obligation under the premarital agreement. His guardian filed for divorce

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

because the husband would run out of money if he had to keep supporting both of them, and would be

forced out of a good nursing home into one that would accept Medicaid. Nonetheless, his guardian could

not maintain the suit because Indiana law did not grant a guardian authority to maintain an action for

divorce.

Even in states whose statutes permit a guardian to file for divorce on behalf of a ward, there can be

obstacles. Where state divorce law requires a finding of intent to permanently separate, an incapacitated

ward may not be able to form the necessary intent. 46

Dispute resolution through binding arbitration

Parties may wish to consider a provision for binding arbitration of a future dispute. An agreement for binding

arbitration is generally enforceable. Binding arbitration can provide a speedier resolution and will afford

privacy. A variety of issues under a premarital agreement may be appropriate for binding arbitration: a

dispute about valuation of an asset subject to the agreement, construction of the agreement, or a claimed

breach. It can also be appropriate to resolve an issue left open by the agreement, such as the particulars of

allocation of property subject to the agreement.

An arbitration clause may be especially useful for a same-sex couple whose access to the courts may be

limited if their dispute must be resolved in a state where their marriage is not recognized. It may not be

useful for a younger couple who are likely to have children. Some issues in a divorce-custody and child

support-may have to be resolved in court in any event; proceedings in two different forums may not be in

their best interests.

A provision for binding arbitration to determine validity of a premarital agreement is not a good idea. The

right to appeal from an arbitrator's ruling is extremely limited. The proponent of the agreement is likely to be

better served by retaining access to the appellate courts if the trial judge gets it wrong.

1

See Griffin v. Griffin, 94 P3d 96 (Okla. Civ. Ct. App., 2004); Baker v. Baker, 622 So 2d 541 (Fla. Dist. Ct.

App., 1993).

2

Wis. Stat. Ann. §767.255(3)(l); Estate of Benker, 331 NW2d 193 (Mich., 1982).

3

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

DeMatteo v. DeMatteo, 762 NE2d 797 (Mass., 2002); Gant v. Gant, 329 SE2d 106 (W. Va., 1985).

4

See Hardee v. Hardee, 585 SE2d 501 (S.Car., 2003).

5

See e.g., Howell v. Landry, 386 SE2d 610 (N.Car. Ct. App., 1989) (presentation of premarital agreement

to wife night before parties' December 31 departure for Las Vegas to get married insufficient to demonstrate

duress where no evidence she was unable to get legal advice on following day before flight).

6

612 SE2d 469 (S.Car. Ct.App., 2005)

7

See Cannon v. Cannon, 865 A.2d 563 (Md., 2005).

8

UPMAA §9(f). The UPMAA has alternative language that can be adopted in states that want to retain the

second-look.

9

Restatement Second, Conflict of Laws §187.

10

511 A2d 1257 (N.J. Super., 1986).

11

21 SW3d 117 (Mo. Ct. App., 2000).

12

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

628 SE2d 546 (Va. Ct. App., 2006).

13

UPAA §6(b); Sims v. Sims, 685 SE2d 869 (Va. Ct. App., 2009).

14

See Sailer v. Sailer, 764 NW2d 445 (N.Dak., 2009); Osborne v. Osborne, 428 NE2d 810 (Mass., 1981).

15

Colo. Rev. Stat. §14-2-307(2); Cal. Fam. Code §1612; Gross v. Gross, 464 N.E.2d 1362 (Ohio, 1988).

16

Restatement Second, Conflict of Laws §187(2)(b).

17

See Recovery Resources, LLC v. Cupido, 818 NW2d 787 (N.Car., 2012).

18

8 U.S.C.A. section 1183a(a)(1); and see Sheridan, "The New Affidavit of Support and Other 1996

Amendments to Immigration and Welfare Provisions Designed to Prevent Aliens from Becoming Public

Charges," 31 Creighton L. Rev. 741 (1998).

19

8 U.S.C.A. sections 1183a(a)(2), (3)(A) and (B).

20

Moody v. Sorokina, 40 App Div 3d 14, 830 NYS2d 399, 2007 NY Slip Op 947, 2007 WL 294218 (App. Div.,

2007); Cheshire v. Cheshire, 2006 U.S. Dist. Lexis 26602 (D.M.D. Fla., 05/04/2006).

21

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

Carlborg v. Tompkins, 2010 U.S. Dist. Lexis 117252 (W.D. Wis., 11/3/2101); Cheshire v. Cheshire, supra

note 20.

22

8 U.S.C.A. sections 1183a(a)(2) and (3).

23

See, e.g., Code of Maryland, Family Law §4-506(d)(9) (protective order may include "emergency family

maintenance necessary to support any person eligible for relief....").

24

See Hutchison v. Hutchison, 2009 Mich. App. Lexis 1594 (7/28/09) (unpub.) (husband's physical abuse of

the wife warranted voiding premarital agreement and award of alimony). VanWagner v. VanWagner, 868

N.E.2d 924 (Ind. Ct. App., 2007) (in divorce proceeding, husband's domestic violence warranted temporary

support over waiver in premarital agreement).

25

UPMAA §10(b)(2).

26

Section 71.

27

Section 71(b)(2).

28

Reg. 1.71-1(b)(6), Example 2; Halsey v. Halsey, 296 App Div 2d 28, 746 NYS2d 25, 2002 NY Slip Op

5952, 2002 WL 1687130 (App. Div., 2002).

29

Section 71(b)(1)(B).

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

30

See Restatement Second of Contracts §191 (1981); Md. Code Ann., Fam. Law §8-103(a) (court may

modify provision of marital agreement relating to custody of minor child).

31

Combs v. Sherry-Combs, 865 P2d 50 (Wyo., 1993); Edwardson v. Edwardson, 798 SW2d 941 (Ky.,

1990); Osborne v. Osborne, 428 NE2d 810 (Mass., 1981).

32

See Uniform Premarital Agreement Act §3(b) (1983) ("The right of a child to support may not be adversely

affected by a premarital agreement."); In re C.G.G., 946 P2d 603 (Colo. Ct. App., 1997); Edwardson v.

Edwardson, 798 SW2d 941 (Ky., 1990); Huck v. Huck, 734 P2d 417 (Utah, 1986).

33

Treadaway v. Smith, 479 SE2d 849 (S.Car. Ct. App., 1996).

34

Akileh v. Elchahal, 666 So. 2d 246 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App., 1996).

35

Avitzur v. Avitzur, 446 NE2d 136 (N.Y., 1983).

36

Scholl v. Scholl, 621 A2d 808 (Del. Fam. Ct., 1992); Minkin v. Minkin, 434 A2d 665 (N.J., 1981).

37

See Hardee v. Hardee, 558 SE2d 264 (S.Car. Ct. App., 2001); Taylor v. Taylor, 832 P2d 429 (Okla. Ct.

App., 1991).

38

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

See Marriage of Ikeler, 161 P3d 663 (Colo., 2007) (enforcement of fee waiver in premarital agreement

may be unconscionable and therefore unenforceable at divorce).

39

See Urbanek v. Urbanek, 484 So 2d 597 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App., 1986); Hill v. Hill, 356 N.W.2d 49 (Minn. Ct.

App., 1984).

40

See Rosenbaum-Golden v. Golden, 884 NE2d 1272 (Ill. Ct. App., 2008) (fee award to wife did not violate

premarital agreement waiver where award was advance against marital assets and husband had much

greater resources).

41

See Hardee v. Hardee, 585 SE2d 501 (S.Car., 2003).

42

See In re Marriage of Burke, 980 P2d 265 (Wash., 1999).

43

901 NE2d 967 (Ill. Ct. App., 2009); see also Marriage of Lane, 2011 Cal. App. Lexis (unpub.) (1/13/11)

(fee waiver did not encompass fees for custody and child support, and had it done so, waiver would have

violated public policy).

44

Walker v. Walker, 765 NW2d 747 (S.Dak., 2009); Lebeck v. Lebeck, 881 P2d 727 (N.M. Ct. App., 1994).

45

2013 Ind. App. Lexis 326 , transfer den. 995 N.E.2d 620 (Ind., 2013).

46

Andrews v. Creacey, 696 SE2d 218 (Va. Ct. App., 2010).

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting

© 2014 Thomson Reuters/Tax & Accounting. All Rights Reserved.

Reprinted with permission from Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting