IRC_PBSP Panay & Cebu Assessment Report

advertisement

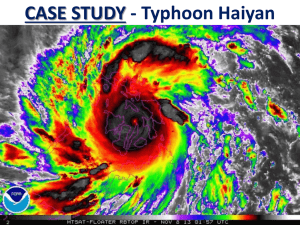

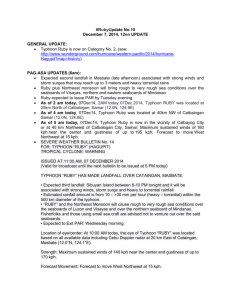

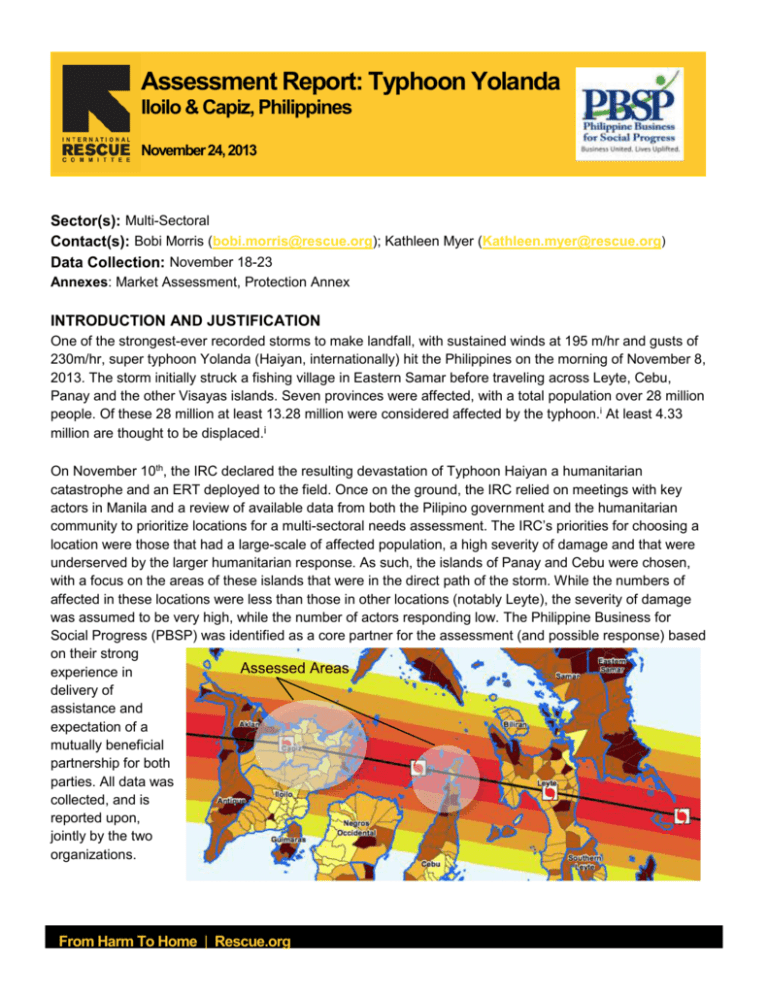

Assessment Report: Typhoon Yolanda Iloilo & Capiz, Philippines November 24, 2013 Sector(s): Multi-Sectoral Contact(s): Bobi Morris (bobi.morris@rescue.org); Kathleen Myer (Kathleen.myer@rescue.org) Data Collection: November 18-23 Annexes: Market Assessment, Protection Annex INTRODUCTION AND JUSTIFICATION One of the strongest-ever recorded storms to make landfall, with sustained winds at 195 m/hr and gusts of 230m/hr, super typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan, internationally) hit the Philippines on the morning of November 8, 2013. The storm initially struck a fishing village in Eastern Samar before traveling across Leyte, Cebu, Panay and the other Visayas islands. Seven provinces were affected, with a total population over 28 million people. Of these 28 million at least 13.28 million were considered affected by the typhoon.i At least 4.33 million are thought to be displaced.i On November 10th, the IRC declared the resulting devastation of Typhoon Haiyan a humanitarian catastrophe and an ERT deployed to the field. Once on the ground, the IRC relied on meetings with key actors in Manila and a review of available data from both the Pilipino government and the humanitarian community to prioritize locations for a multi-sectoral needs assessment. The IRC’s priorities for choosing a location were those that had a large-scale of affected population, a high severity of damage and that were underserved by the larger humanitarian response. As such, the islands of Panay and Cebu were chosen, with a focus on the areas of these islands that were in the direct path of the storm. While the numbers of affected in these locations were less than those in other locations (notably Leyte), the severity of damage was assumed to be very high, while the number of actors responding low. The Philippine Business for Social Progress (PBSP) was identified as a core partner for the assessment (and possible response) based on their strong Assessed Areas experience in delivery of assistance and expectation of a mutually beneficial partnership for both parties. All data was collected, and is reported upon, jointly by the two organizations. From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 2 STATEMENT OF INTENT Objective(s) The overall objective was to determine if an emergency response to assist people affected by typhoon Yolanda is 1) needed, and 2) feasible. If so how can IRC and PBSP programs (Health, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene, cash/vouchers, Protection, NFIs) can be tailored to fit the priorities, specific needs and culture of the affected population. Assessed Locations Core Questions What is the scope and severity of damage? What need do populations prioritize? What are the gaps in food needs due to disruption? Where do people buy food? How much does it cost? Has there been a change in severity of need? What is the current market situation? What are typical prices for key goods? Can traders increase supply to meet demand? How long to restock if sold out What is the generalized state of WASH infrastructure? (Latrine coverage/use/types, Water quality/quantity/access/storage and functionality) What are the current conditions of health facilities (including hospitals) in terms of staff/supplies/capacity to respond to needs? What are the general safety concerns? Has there been any increase in violence; separated families, threats to women & girls, men & boys? Province Capiz (total population 2010: 719,685) Municipalities Reached Panay Panitan Pontevedra Jamindan Tapaz Sigma Dumalag Ma-ayon President Roxas Pilar Iloilo (total population 2010: 2,230,195) Carles Balasan Estancia Batad San Dionisio Sara Ajuy North Cebu (total population 2010: 2,619,362) Lemery Barotac Viejo Daabantayian Tabogon Madridejos Bantyan Barangays Assessed Libon Cabugao Binuntucan Agambulong Bag-Ong Barrio Matangcong San Rafael & Santo Angel Tuburan Ibaca Dayhagan & San Fernando Punta Salvacion Bayas & Bito-On Alinsolong & Embracadero Sua Aldeguer Puente Bunglas Tabunan Santiago Pajo, Dailingding & Lanao Ilihan & Mabuli Maalat, Bunakan & Tabagak Kabac L S O X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X F X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X METHODOLOGY The methodology was adapted from the IRC’s Emergency Preparedness and Response Unit’s Emergency Accountability Framework assessment guidelines and designed to cover the multiple sectors listed above. The assessment relied primarily on qualitative data surrounding ‘big picture’ questions regarding how respondents are returning to normal life. Four assessment teams were created in order to cover as much From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 3 geographical area as possible in a two to three day period. Each team covered a designated axis within Capiz, Iloilo and North Cebu, with a goal of reaching 30 separate barangays within a three-day period. Due to time and information constraints, assessed locations were purposefully sampled, and as such results are not representative of all locations in the assessed municipalities, but only of the barangays assessed. In each location targeted, the assessment made use of various primary data collection methods including: key informant interviews, focus group discussions and observation. In 32 of the barangays visited due to the travel times (poor roads) the team was unable to assess, however they conducted a mapping exercise from within the vehicle noting functioning/nonfunctioning infrastructure and observed level of shelter and agriculture impact. The results of this mapping exercise as well as the related qualitative data and exact assessment locations can be found here: http://cdb.io/1h6jiOm. Tools and Sampling Two types of assessments were conducted. A long assessment consisted of an observation walk, a focus group discussion (FGD), and a long key informant interview. A short assessment consisted of an observation walk and a short key informant interview. Locations were chosen purposively as each team drove along their assigned axis, with a long assessment done each day in the barangay From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 4 expected to have the most significant level of damage and destruction and the largest scale of needs. A minimum of three short assessments were to be done in additional barangays spread along the route traveled on a given day, with no two assessments taking place in neighboring locations and locations chosen based on the appearance of large scale need. Locations for each type of assessment can be found in the table on the previous page. Municipalities were one or more assessment was conducted are underlined in red in the maps on the previous page. Tools Long Key Informant Short Key Informant Observation Checklist Focus Group Discussion Guide Description Targets a community leader as respondent in selected villages and covered multi-sectoral needs. Community leaders (men and women) found upon arrival in each barangay. Targets a community leader or member as respondent using a shortened tool to address key concerns for each identified sector. Community leaders (men and women) found upon arrival in each barangay. Guide for assessment team that seeks observation on each identified sector and overall thoughts on damage and coping. Completed based on observation and discussion with community members walking through the barangay. FGDs will target women and discuss key needs, coping mechanisms and protection concerns using open-ended questions and pile ranking. Women were selected upon arrival in a barangay from any women within proximity to the assessment team, once permission to assess had been granted by the barangay captain. Data was analyzed using Excel to count and quantify responses to closed questions and tease out themes found through FGDs and noted during observation walks. Limitations This needs assessment is not representative in nature and based on a purposive sample of barangays, assessment team observations and the responses were from a very select number of barangay residents that were sampled either conveniently or purposefully. While some interviews were conducted by the assessment team in English, the majority of data collection relied on-the-spot translation from the IRC’s partner organization PBSP. While these members of the assessment team had been trained on each tool and were aware of the assessment’s objectives, it is impossible to capture what could have been lost in translation during data collection. Furthermore, the presence of a male translator for four of the team’s focus groups could have very likely influenced the responses of the female participants. Lastly, due to the informality of the focus groups and their locations, men were present during discussions with two separate groups of women, which could also have influenced the women’s responses. Ethical Considerations The assessment team placed a high priority on ensuring a rapid assessment focused on key, big picture questions, in order to avoid over-burdening the population with information demands or inadvertently causing harm by probing into sensitive subjects without have a response in place to address them. Additionally, the IRC tried to maintain a low profile to avoid raising expectations. Informed consent was sought from all respondents and no names or personal information was recorded. From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 5 KEY FINDINGS Geographical Variations The island of Panay (where Iloilo and Capiz are located) is considered the fishing center of the Philippines, particularly the sea off of the east coast of the province of Iloilo (source: PBSP). Each Municipality is made up of barangays (sometimes over 30) that can be considered geographically spread-out villages (called Sitios or Puroks), with one center or ‘poblacion’ per municipality. On the whole, the municipality poblacions were observed to be lively market centers with a relatively strong infrastructure (piped water, many concrete buildings, electricity, diverse markets) prior to the typhoon. The barangays outside of the center however were observed to be significantly more rural with family incomes from fishing, agriculture and some tourism (along the coast) and primarily agriculture in the interior. The primary roads run along the coast (with the exception of the road from Iloilo city to Roxas city) and the development along the road (as opposed to the development off the main road) was apparent. Despite this development diversity, areas of poverty and large proportions of families living in bamboo and wooden structures (which were largely destroyed) prior to the storm were observed throughout all barangays visited, whether they were poblacions or more remote. One clear difference between the poblacions and the more rural barangays was that the poblacions were more likely to have functioning hardware, money transfer, NFI and food stores (with diverse and sufficient stock), as well as more likely to have functioning health services and potentially easier access to assistance (as most assistance is organized via the municipality poblacion at the moment -comparisons of observation checklists and mapping data). The assessment teams visited focused on more remote barangays in an attempt to understand the needs of those with the least access to services. Other differences in need noted by geography related to the barangay’s proximity to the coast, and number of shelters that were situated directly on the waterfront. Storm surges in several barangays were anecdotally quoted to assessors to be between 10 and 15 feet. The storm surge in these locations resulted in destroyed homes, similar to the wind in other locations, however those families whose homes were affected by the surge also lost the majority of their belongings and much of their housing materials, as they were washed out to sea. The assessment teams visited both coastal and inland municipalities and barangays in an attempt to understand these differences. Community Need Ranking The assessment team sought an understanding of what communities themselves have identified as their recovery needs, as well as how they prioritized these needs by applying three different methods of inquiry and triangulating the results. In each assessed 30 25 Prioritized Needs 20 15 10 5 0 From Harm To Home | Rescue.org Kis FGDs IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 6 barangay (29), a key informant (or group of gathered key informants) was asked to rank the top five most urgent needs of people in this community right now. These responses not were prompted and the final list was grouped in categories (i.e. “boats” was grouped with livelihoods). Additionally, in the twelve barangays where focus groups were conducted, the participants were asked to complete a pile ranking exercise whereby they were given stones and freely elaborated a list of needs and then allotted stones to the needs which they prioritized the most. In analyzing the data from the key informant interviews, responses were weighted, given where on the scale of 1 to 5 each response fell and then these values were summed. Combined results of key informants (KIs) and focus groups (FGDs) at right show the total rank1 for each given category of need. 2 While shelter, food and livelihoods emerged as the priority needs through both the key informant interviews and focus groups, results differ slightly after that point. The key informant rankings placed a higher degree of importance on medicines and clean than the focus groups did and water, while focus group participants were more focused on money and education. Lastly, during observation walks, the assessment teams ranked aspects of the typhoon’s impact on each location and community recovery on a scale of 1 to 5. These observations also mirror the needs prioritized by communities, with the shelter needs receiving the highest average rank of 3 (signifying over 75% damage/destruction but community is beginning to cope) and needs relating to water and health receiving lower average rankings of 2.5 and 2 respectively (approximately 50% damage). Shelter and NFI % of Houses in 21 Bgy by level of The most visible need of communities damage in Panay (21 KIs) and individuals affected by Typhoon 1% Yolanda is support to rebuild their shelter. According to the observational data in 34 15% % unaffected barangays, while some families resided in % destroyed cement structures prior to the storm, the majority inhabited wooden or bamboo % damaged 84% structures. Both types of shelter received substantial damage. Cement homes lost their roofs, were crushed under falling trees, and in some cases were swept away in the storm surge (most notably in San Dionisio), while most bamboo and wooden structures crumbled in the wind and were either blown away, collapsed in a pile of debris, or were swept away by the storm surge. In the barangays assessed in Iloilo and Capiz3, the observed percent of shelters completely destroyed ranged from 25% to 98% (not including shelters which were partially damaged). This was confirmed by key informants in these same 22 barangays whose total report of severely damaged or destroyed homes in the 1 For KIs and FGDs this rank is equal to the sum number of times each category was mentioned as the first, second, third, fourth or fifth priority multiplied by a relative weight assigned to each rank, and then normalized (assuming 100 total points possible). 2 Note that water was mentioned in the focus groups but did not receive any stones. 3 This data was not collected from Cebu From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 7 barangays assessed was approximately 84% of shelters, with another 14% damaged and less than 2% unaffected4. While some barangays were seen to be more in need of shelter assistance than others, it is clear that all locations in the direct storm path were heavily affected. While most locations were actively setting up some sort of make-shift shelter at the time of the assessment (6/6 focus groups in Panay and 3/5 in Cebu noted that this was a common coping strategy), it was unclear, and in some cases unlikely that these shelters could be considered 'rebuilt' (i.e. their size, safety, security provision, lack of protection from the elements and even location suggested that many were not structures that could be habitable for an extended period of time). Focus group participants in Panay noted that when it rained families were forced either to stay in the rain (as many of these structures are not weather-proof) or to flee to public buildings. This is of particular concern in the locations where coughs, fevers and flus were reported by key informants and focus groups to be affecting children and/or adults after the typhoon (4/7 locations where this was asked in Panay). Two focus groups in both Panay and Cebu noted that many were sharing the homes of their relatives/neighbors. Additionally, in Panay there were at least two locations visited where only a few community members were actively building shelter, and the others appeared to be inactive, potentially due to shock, and another location where the majority of families were noted by the key informant to be living in the open. The rebuilding efforts of these families are likely to be hindered as prices for shelter supplies such as nails have anecdotally risen (example: nails increased in price from 25-67% “We have the will, we have dependent on the location and type of nails, while galvanized sheeting the drive, but we have no has reportedly increased around 60%). This is limiting the supplies for options to rebuild” reconstruction to found materials (including old nails) for many families - female in FGD (unsolicited response in six focus groups across both locations and observational data). While the determination of communities to recover is laudable and clearly apparent, there are several ongoing protection concerns that have arisen from this scenario. First, much of the debris from the storm, particularly in areas of the storm surge, had not yet been removed prior to families beginning to build these small structures. In one barangay, women reported feeling unsafe due to lack of adequate shelter, and being afraid of ‘strangers and community members at night.’ Parents report children as upset and ‘wanting to go home, as well as concern for unsafe shelter for their children. In two barangays, widows reported that they were distraught and scared with no way to obtain resources to rebuild, and no access to skills or labor to help them properly construct a home. There is a notable large-scale lack of access to adequate shelter supplies for the poorest populations. When focus groups in Panay were asked which groups of persons in their community they expected would have the hardest time coping and recovering from the effects of the storm, the elderly (3/7 FGDs), the sick and disabled (3/7 FGDs), single mothers and widows (3/7 FGDs), the very poor/those who do not have any 4 Statistics calculated on the number of houses prior to the typhoon, against the number of houses reportedly destroyed and reportedly damaged at the barangay level. They are not intended to be representative of any location that was not visited in this assessment. From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 8 family to send them money (2/7 FGDs) and those who were particularly traumatized, including mothers and children (3/7 FGDs) were noted to be of the greatest concern to the community. Additionally, as noted in the geographical variations above, while many affected families have lost a larger portion of their belongings in the storm, in the inland areas this observationally appears to be mostly due to rain and wind damage. In the coastal barangays however, it was observed that the majority of possessions were washed out to sea. This was confirmed by two focus groups in Panay, one in a barangay with a 15 foot storm surge who prioritized clothing, kitchen utensils, soap, sanitary supplies for women and girls, and other NFIs as core needs. Some women focus groups stated that with the scant resources that remain in households, tough choices have to be made to buy food over soap, clothes, medicines, sanitary napkins, and `education supplies. Food Security and Livelihoods Food was highly prioritized by key informants and focus group participants and was observed as a need by the assessment team. However, in all areas assessed, the government or other local actors were providing food distributions (often with supplies for two days). During focus group discussions, participants discussed coping mechanisms to deal with their current food needs, including loans/begging from neighbors (4/7 FGDs in Panay, 1/5 in Cebu) and remittances (4/7 FGDs in Panay 1/5 in Cebu) from family abroad or packages from family in Manila. Others noted that families are limiting their food to one meal a day, intake to rice only, and were eating their own crop of rice, rather than selling it, for fear of going hungry in the coming months (3/7 FGDs in Panay). One focus group on each island mentioned concerns regarding taking loans from neighbors and informal sources, noting that it can cause conflict among community members, and that interest on informal loans is 10% and collected on a weekly basis. Without a means to rebuild their livelihoods, these families may be increasingly at risk of rising, un-payable debts, or of not being able to buy or borrow food when the food relief begins to subside. On this point, focus groups also expressed concerns with how they will continue to access food when and if these short-term distributions and support from friends and family cease. Yet the assessment team found indicators that food insecurity may be less of an issue if livelihoods are rebuilt quickly: markets continue to function in poblacions, municipality centers (however in larger municipalities, these centers can be harder to access for some), and each assessed barangay still had small shops that function. Though some were damaged or destroyed in the storm, many of these are already back up and running. All of the major transportation roads for the movement of goods are open and clear of debris, and the majority of stores and suppliers in larger towns and cities are operational. The IRC is currently conducting a more in-depth assessment of the market, but is hopeful that due to the high level functioning of markets in the Philippines on the whole and the strong transportation network, that the market system on Panay will recover fairly From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 9 rapidly. If this is the case, goods and services including food can be expected to be readily available, provided communities have the resources to afford them. Livelihoods in the most affected areas of Panay were heavily dependent on agriculture (rice, fruit trees, livestock) and fishing (for areas directly along the coast). A full assessment of agriculture damage has not yet been completed, though the Pacific Disaster Center estimates put the damage at 4 to 10 million USD for Iloilo and 10 to 25 million USD for Cebu. Many agricultural areas visited in Iloilo during the assessment had significant crop damage (bananas, sugar cane, coconut and other trees were heavily damaged, if not entirely destroyed in some areas; in some areas rice crops were also affected, though a number of communities harvested before the typhoon). Fishing communities appear to have taken the most damage overall, because of storm surge, loss of belongings, as well as their livelihoods being damaged. One barangay visited noted that there were 266 fishing boats before the storm, but only one remained. In another fishing barangay (expected to also have several hundred boats) only three boats could be seen on the shore, and all three were damaged. Many of these fishermen lost not only their boats, but also their nets and other fishing supplies in the storm surge. Prior to the typhoon, farmers and fishermen were often dependent on their farms and fishing for their own food source, but also sold the surplus for income. The devastation of the fishing industry, as well as the damage to the farming industry puts families engaged in these two activities at a high risk of future food insecurity and a general inability to recover from the crisis, if their livelihoods are not rapidly restored. Cash Both food and shelter coping/recovery have close links to the availability of cash at the household level. Focus groups prioritized cash as a need, without being prompted, and when asked what they would spend the money on it was predominately materials for shelter or livelihoods. Observational data noted that both food distributions, as well as access to supplies for rebuilding/ and types of supplies needed per each house to rebuild, varied substantially. While some communities have received multiple food distributions, some have received only one. Conversely, while some homes lost their roofs, others were able to recover their roofing material, but are lacking other supplies needed to rebuild. A need for cash was also noted in focus groups for the following needs: › Reclamation of lost documentation (costs from 100 to 250 pesos noted)- documentation is needed to claim any assistances from government social/senior citizen welfare programs. Some land claim documentation was also lost, and must be paid to replace. (5/7 FGDs in Panay 0/5 in Cebu) › Paying to travel to the poblacion to purchase needed goods, access health care, and purchase medicines (1/7 FGDs in Panay, 0/5 in Cebu) From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 10 The combination of open, accessible and relatively stocked markets, the variation of needs at the household level, and functioning money transfer mechanisms, led IRC to move directly from this assessment into a more formal assessment of market systems to understand if an unconditional cash transfer program may be feasible. The results of this follow on assessment will be issued as an annex to this report, when complete. Health Care Of the 30 barangays assessed 24 had health facilities prior to the storm and of these 24 none were destroyed, though 14 were damaged in some way (KIs). A total of 27 key informants responded to a question regarding the functionality of the health center their communities typically used before the storm, and 20 of them noted they were functional, while 7 (all in Panay) noted they were no longer functioning. According to key informants, Barangay health workers are present and active in most communities. In Panay an increase in diarrhea was noted by 6 of 20 KIs, while several key informants (6) and focus groups (2) noted an increase in coughs and fevers in the last week (particularly in children), and stated this was in connection to lack of adequate shelter. However none of the assessed locations in Cebu noted any above normal increase in diarrhea. Despite the damage to some health facilities, observations showed that the majority of health services were functioning generally, as they were before the typhoon. While some (3/7 FGDs in Panay) mentioned a concern regarding money to pay for transport and medicines (medicines and health care were also a priority for 15 out of 29 key informants), in large part communities noted even when their BHC was not functioning, they either had access to the Rural Health Unit or a mobile team had come to the Barangay. Water and Sanitation Of the 20 communities where access to water was observed, eight of the communities had no problem with access to water, as the situation was the same as it was before the typhoon. In the other 12 communities the storm had one or more impacts on their access to water including the following: › One or more of several water sources in the barangay was damaged (but not all of them) – This finding was only in Panay, anecdotally in Cebu many piped systems were running with no issues. › With the community now relying on water from a hand pump or well, as opposed to piped water from the district or a spring, the distance to this source was cited as a concern or difficulty in Panay, but not in Cebu › Lack of electricity and access to pumped spring water has forced people to buy water in town 5 or boil well water in Panay. In Cebu it was normal to purchase water, and some barangays had kiosks for this purpose The assessment team recorded the above water access issues during observation and/or key informant interviews. Furthermore, when asked directly during key informant interviews five out of 28 key informants responding reported that there was not enough water to meet their community’s needs (all of these reports were from Panay) and nine key informants were asked about available containers for water collection and 5 With prices increasing at one location From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 11 one notes that their community did not have enough. The assessment team observed people using bottles and open buckets to collect water, as households were likely unprepared to take on water collection. Chlorination was addressed during long KIs as well and it was occurring in six of eight the barangays where long KIs were completed. Notably, in Cebu, the Barangay Health Workers were chlorinating many wells on a weekly basis. The IRC’s Senior EH coordinator noted that some of the groundwater available in coastal areas is brackish and therefore develops an unpleasant taste when mixed with chlorine, therefore chlorination may not be well received in these areas. The most common type of latrine observed and reported was a pour or pipe flush latrine, with 11 of 27 key informants that responded to the question reporting that all (2 in Cebu) most (2 in Panay, 3 in Cebu), some (2 in Panay) or a few (2 in Panay) community members were currently relying on open defecation (in Cebu latrine coverage was noted to be very low prior to the crisis). Ten key informants mentioned pit latrines as well, but these were in place prior to the storm and continued to function. Of the five key informants responding to sanitation questions during a long interview, two noted a change in type of latrine used after the storm, one because most of the Barangay’s flush latrines were destroyed during the storm or the walls surrounding them were, many residents were relying on open defecation at the time of assessment. However, this particular situation could be considered an outlier, compared to other assessed villages. The assessment team’s average priority ranking for general sanitation infrastructure was less than 2, as many latrines were still seen as functioning, though there was a large amount of sharing between families and neighbors. Disease and illness resulting from poor environmental health infrastructure were not obvious to the assessment team. While residents did note an increase in fever and coughs since the storm, 6 only 6 out of 20 villages responding reported an observed increase in people with diarrhea. Though none considered it an extraordinary increase. Electricity There was no available electric supply throughout the entire surveyed area. It can be inferred that many respondents expressed a prioritized need for electricity as they were dependent on the power grid prior to the typhoon. However, the assessment did not collect information as to how many of the assessed villages had access to electricity prior to the storm (though all visited barangays in Cebu had it). Informants were asked about access to power during long KI interviews and six out of eight reported that they had no access, while the remaining two reported the use of some generators, as well as kerosene, candles and bonfires for light. One of the main concerns of focus groups in Cebu was that they did not have any information about when power would be restored, though the provincial government had provided some generators to re-establish piped water, and many barangays had done so within 5 days after the storm. In Panay absence of power has severe knock-on effects in relationship to environmental health and health, as many communities are used to pumped water for drinking, bathing, and having water available for flush latrines, as well as a disruption to the cold-chain. Sanitation and hygiene habits could change as communities cope with less water, leading to the spread of disease. However, in Cebu, no barangays reported that they did not have enough water. 6 And this could be confirmed with observation From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 12 Access to power also creates protection concerns, as several (5/7 in Panay, 3/5 in Cebu) focus groups discussed concern over theft due to the lack of light at night. One of these groups in Panay noted that their barangay had initiated a curfew because many people were feeling unsafe at night. Of the two groups in Panay that did not identify safety issues around light and electricity, one mentioned that theft was not a concern because there was nothing left to steal. Education Though education was identified as a need by beneficiaries, the “There is not enough food for assessment team did not specifically address education needs through our children … we do not other data collection tools, other than to note the number of schools mean to yell at our children, damaged or destroyed during long key informant interviews (5/9 but we do” schools found in the locations where informants were asked). This was - female in FGD confirmed by observations from the team while driving throughout the area noted that many schools sustained significant damage, roofs were blown off and schoolbooks destroyed from the water. Additionally, broader child protection issues were investigated and several concerns are as follows: › Though the government has noted that schools should resume immediately, many schools are damaged, or still have families residing in them. Focus group participants in Panay noted that they are concerned that schools will not open as quickly as planned, and that supplies and uniforms had been damaged (though observationally, teachers remain in the communities). Likewise two of five focus groups in Cebu noted that the school had been badly damaged, and was not yet safe for children. › Mothers in 5/7 focus groups in Panay reported children suffering both from physical illnesses as well as trauma from the typhoon (increase in crying, general confusion regarding the loss of their homes). › Parents in 2/7 focus groups in Panay noted that that children were being asked to work more to help in the recovery, and that parents did not have time to give quality attention to their children, but rather found themselves loosing patience and yelling at their children more often due to household stress in the prioritization of scant resources. › Mothers in 2/7 focus groups in Panay noted their concern that older children would drop out of school to help the family. RECOMMENDATIONS The following recommendations proceed directly from the data analysis above. They are intended for action by the IRC and PBSP as well as any other actors that have the capacity to respond. The recommendations that the IRC is currently working to respond to in collaboration with PBSP in the Municipalities of Batad, Sara, San Dionisio and Ma-ayon in Panay and x and y in Cebu7 are underlined. These locations and/or other types of response may be expanded upon in future programs by the same. *Note: the following recommendations apply to all assessed areas. To date, a mapping of actors shows that the majority of humanitarian response is focused on the coastal areas. While the needs are extensive given 7 These prioritized locations for the IRC and PBSP are dependent on need, accessibility and the current understanding of other actors plans to respond (to avoid overlap) however, they are currently tentative and may change. From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 13 the storm surge, the IRC and PBSP found comparable damage to inland areas, which must not be ignored in response. 1. Shelter Assistance To address both physical and psychological protection risks to heath urgent support should be provided for the reconstruction of safe and secure shelters. This should either be provision of supplies in-kind with technical assistance for construction (per the shelter cluster’s strategy in Roxas), or via cash/voucher assistance. Special consideration should be given to widows, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups that may not be able to construct the shelters themselves. 2. Cash/Voucher Assistance Many of the outstanding needs (shelter, food, NFI) can be addressed through either cash or vouchers if the market is appropriately functioning. Given that need priorities vary by household, a market assessment of NFI, shelter and food availability, access and ability to respond must be conducted immediately, and assistance provision tailored to the findings.8 One option would be cash-for-work for skilled labors to assist the identified most-at-risk groups to rebuild their shelter. 3. Livelihoods Assistance Given the high prioritization of the affected population of resuming livelihoods as quickly as possible, as well as the ability of livelihoods restoration to improve household ability to cope with food, shelter and NFI needs, and risk mitigation for expressed protection concerns - the provision of fishing and farming (and potentially other livelihoods support for other pre-existing income-generating activities) should be provided in cash or kind as a priority. Interventions must take into account the roles of men, women, and boys and girls within these economic ecosystems, actively ensuring equitable access, opportunity, and leadership in livelihoods assistance. 4. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Assistance Distribution of jerry cans and water purification at the household level should be provided in locations where in-door water supply was previously available, but is no longer functioning. In the medium term, in collaboration with the GoP, priority damaged water infrastructure should be restored, and locations where open defecation is a concern, support to hygiene messaging and reconstruction of latrines/toilets provided. As an interim measure, while broken systems are repaired, installation of communal water storage tanks with tap stands, or supporting local kiosk systems would be appropriate. 5. Health Care Assistance Health actors should focus on rehabilitating select damaged health centers, re-establishing the cold chain, and continuing to offer mobile clinic support (as was found to be functioning in underserved areas) until the GoP is able to fully re-establish services. 6. Provision of solar lighting Given the expressed protection concerns regarding safety at night, and the inability for communities to communicate without power to charge cell phones and access information (as networks have begun to be restored), a distribution of solar lights with phone charging capacity, focusing on areas that are unlikely to have electricity restored in the coming month should be prioritized. 8 The IRC began a market assessment of NFI and shelter goods on November 22, ACF has noted an intention to begin a market assessment focused on food security on Monday, November 25 th. From Harm To Home | Rescue.org IRC • EPRU • ASSESSMENT REPORT: TYPHOON YOLAND NOVEMBER 2013 • 14 7. Child Protection The re-opening of schools should be prioritized , and support given to the GoP in the rehabilitation of damaged schools. In locations where schools do not re-open within the next two weeks, temporary schools some form of child friendly activities should be created with existing community resources (teachers, community structures) in order to remove children from the stressful environment of reconstruction and minimize ongoing trauma by prioritizing the return to a normal schedules and protective (both physical and emotional) environments. ANNEXES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Compiled Data KI Assessment tools Observation Assessment tool Focus Group Assessment tool Map of open/closed infrastructure and assessment locations with data table Market assessment report Protection assessment highlights i OCHA Sitrep 15, Nov 21, 2013 From Harm To Home | Rescue.org