LITTLE ST. GEORGE ISLAND

AN AUDUBON FLORIDA SPECIAL PLACE

By Susan Cerulean

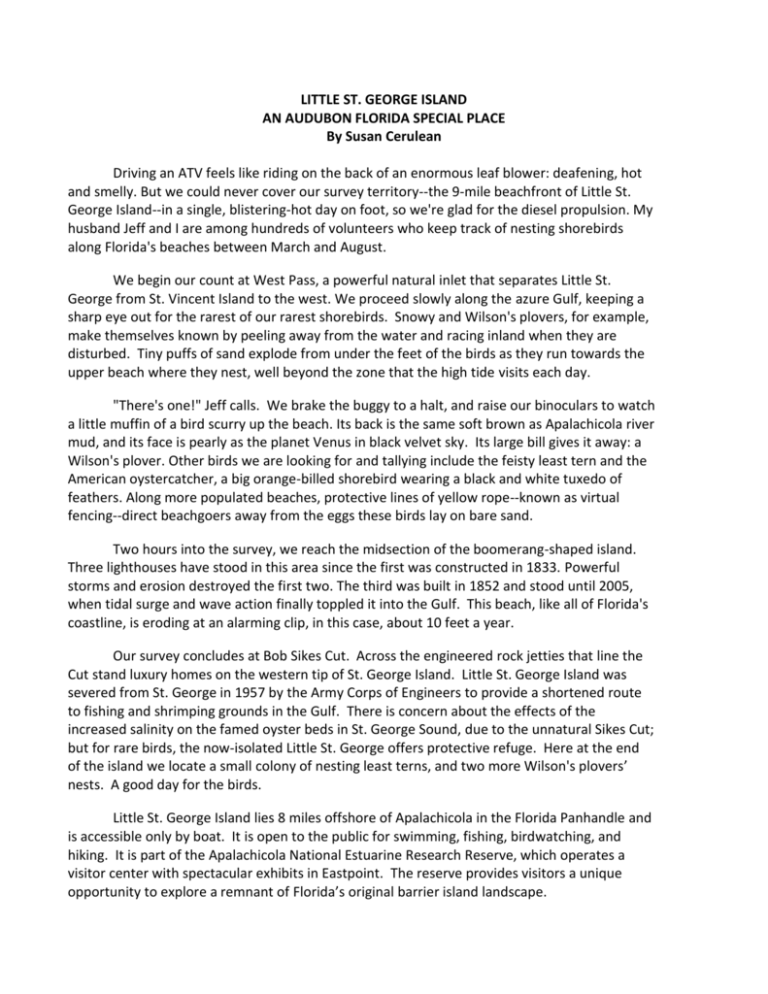

Driving an ATV feels like riding on the back of an enormous leaf blower: deafening, hot

and smelly. But we could never cover our survey territory--the 9-mile beachfront of Little St.

George Island--in a single, blistering-hot day on foot, so we're glad for the diesel propulsion. My

husband Jeff and I are among hundreds of volunteers who keep track of nesting shorebirds

along Florida's beaches between March and August.

We begin our count at West Pass, a powerful natural inlet that separates Little St.

George from St. Vincent Island to the west. We proceed slowly along the azure Gulf, keeping a

sharp eye out for the rarest of our rarest shorebirds. Snowy and Wilson's plovers, for example,

make themselves known by peeling away from the water and racing inland when they are

disturbed. Tiny puffs of sand explode from under the feet of the birds as they run towards the

upper beach where they nest, well beyond the zone that the high tide visits each day.

"There's one!" Jeff calls. We brake the buggy to a halt, and raise our binoculars to watch

a little muffin of a bird scurry up the beach. Its back is the same soft brown as Apalachicola river

mud, and its face is pearly as the planet Venus in black velvet sky. Its large bill gives it away: a

Wilson's plover. Other birds we are looking for and tallying include the feisty least tern and the

American oystercatcher, a big orange-billed shorebird wearing a black and white tuxedo of

feathers. Along more populated beaches, protective lines of yellow rope--known as virtual

fencing--direct beachgoers away from the eggs these birds lay on bare sand.

Two hours into the survey, we reach the midsection of the boomerang-shaped island.

Three lighthouses have stood in this area since the first was constructed in 1833. Powerful

storms and erosion destroyed the first two. The third was built in 1852 and stood until 2005,

when tidal surge and wave action finally toppled it into the Gulf. This beach, like all of Florida's

coastline, is eroding at an alarming clip, in this case, about 10 feet a year.

Our survey concludes at Bob Sikes Cut. Across the engineered rock jetties that line the

Cut stand luxury homes on the western tip of St. George Island. Little St. George Island was

severed from St. George in 1957 by the Army Corps of Engineers to provide a shortened route

to fishing and shrimping grounds in the Gulf. There is concern about the effects of the

increased salinity on the famed oyster beds in St. George Sound, due to the unnatural Sikes Cut;

but for rare birds, the now-isolated Little St. George offers protective refuge. Here at the end

of the island we locate a small colony of nesting least terns, and two more Wilson's plovers’

nests. A good day for the birds.

Little St. George Island lies 8 miles offshore of Apalachicola in the Florida Panhandle and

is accessible only by boat. It is open to the public for swimming, fishing, birdwatching, and

hiking. It is part of the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve, which operates a

visitor center with spectacular exhibits in Eastpoint. The reserve provides visitors a unique

opportunity to explore a remnant of Florida’s original barrier island landscape.

This column is one in a series from AUDUBON FLORIDA. Susan Cerulean is the editor of five

anthologies about Florida; she also wrote Tracking Desire: Journeys after Swallow-tailed

Kites(University of Georgia, 2005), and has completed Coming to Pass, a manuscript describing

changes to the northern Florida Gulf coast as sea level rises. For more information about Little

St. George Island, see http://www.dep.state.fl.us/coastal/sites/apalachicola/ For more

information about Audubon Florida and its “Special Places” program visit

www.FloridaSpecialPlaces.org. All rights reserved by Florida Audubon Society.

A dining oystercatcher: David Moynahan Photography

Pouncing Pelican: David Moynahan Photography

St. George Sound Oystermen: David Moynahan Photography