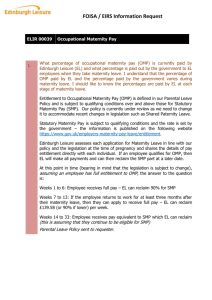

Report on Maternity, 2014 (doc)

advertisement