Review_-_sexual_life_of_savages

advertisement

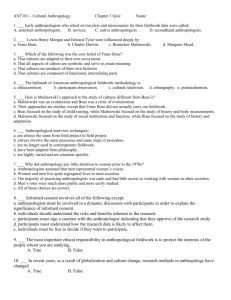

1 Review: The Sexual Life of Savages, by Bronislaw Malinowski Jesse Tomlinson Student Number: 2518408 Date of Completion: 07/05/2013 1 2 Table of Contents Introduction – page 3 Subject – page 3 Site and Time of Research – page 4 Research Questions and Answers – page 5 Theory and Concepts – page 5 Methods – page 6 Main Data and Argument – page 6 Textual Composition – page 7 Discussion – page 7 Conclusion – page 11 Bibliography – page 13 2 3 Introduction Bronislaw Malinowski, writer of the 1929 work The Sexual Life of Savages, can be considered as one of the forefathers of modern social anthropology, especially in how anthropological fieldwork is now carried out. In his second instalment of a trilogy of detailed, complex and intimate, in every sense of the word, works on the Trobriand Islanders of the Western Pacific, Malinowski relays the personal lives and complex relationships between kin, sexual partners and members of different rank, as well as social and cultural interaction between Trobrianders that could be considered the mundane facts of life. The Sexual Life of Savages speaks volumes not only for the lives of Trobrianders on a day to day basis, but is also an example of the shift from what was considered ‘armchair anthropology’ toward participant observation and extensive fieldwork, and an advancement in anthological theory in the emerging post-colonial world. Malinowski returned to the Trobriand Islands after the success of his first work, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), predominantly living in the village of Omarakana and living with those he was studying. His integration into Trobriand society was practically total, prompting one reviewer of his work to suggest that he became a ‘personal friend’ of many of the Trobrianders (Stern, 1930, p. 469). The Sexual Life of Savages is a presentation of the facts the Malinowski’s fieldwork yielded; the relationships between community members on a sexual, the roles that each person fulfils in the lives of others and in the context of society, the rituals they perform and observe and all other part and parcel of village social life. 1.1 – Subject The subject of Malinowski’s ethnography is the society of the Trobriand islanders, and specifically the social relationships that bind Trobriand communities together. Malinowski focuses on these relationships in different chapters, with different sections designated for relationships between lovers and spouses, children and parents, those from different social ranks, and between men and women as a whole, among other subjects. The discussion of 3 4 the roles between men and women remains a constant throughout the book, especially in his discussion of the division of labour, practicing of rituals and magic, and roles in intimate relationships. However, with the title of the ethnography alluding to a theme of sexuality, a large part of the work is comprised of description and analysis of sexuality, sexual relations and morality, and how it infiltrates everyday Trobriand life from a very early age. This discussion of sex is extensive, although it more often than not contributes toward the discussion of the roles of individuals within a relationship, often being used as context when discussing social rules and obligations. 1.2 – Site and Time of Research The publication of Malinowski’s work came at a time of great change in the discipline of anthropology. Theorists had begun to move away from ‘armchair anthropology’, the practice of studying the subject from second hand research in the comfort of One’s study, and had begun to witness the field of interest first hand in the form of fieldwork and participant observation. Malinowski’s work also represents a shift in the perception of the foreign, paving the way for universal theories of society, namely structural-functionalism, rather than working under the dichotomy of civilized vs. savage and evolutionism. This revolution in anthropology occurred in a time of post-colonialism, with cultures starting to be studied as counterparts rather than vassals. The setting for the ethnography is also important, in context to the era. Even Malinowski himself, depicting them as ‘Argonauts’ in his first ethnography and ‘savages’ in his second title, considered the Trobriand Islanders as exotic. However, whether these terms are used by Malinowski with tongue-in-cheek is a subject of debate, although the terms used tell the reader volumes about the type of language used when referring to different cultures at the time, and in turn prevalent social attitudes at the era. 4 5 1.3 – Research Questions and Answers The sexual lives and habits of the Trobriand Islanders comprise the core of Malinowski’s investigations. In the first sentence of his introduction, Malinowski states ‘I have chosen for this book the plainest, that is the most truthful title, partly to contribute towards the rehabilitation of the indispensable and often misused term sexual…’ (Malinowski, 1929, p.xxiii). Malinowski’s investigation into the sexual life of Trobrianders yields further sub-questions, such as the previously mentioned roles of men and women, the role of magic and rituals, and the family unit and kinship relations, among other themes. However, sexuality, sexual behaviour and morality remain a constant frame of reference throughout the ethnography, often used as a contextual tool when discussing the aforementioned themes. In essence, Malinowski’s main research question is to discover the meaning of sexuality among Trobrianders in relation to western definitions, and discuss the similarities of the two concepts by extensively discussing the social and cultural lives of the Trobrianders Islanders. 1.4 – Theory and Concepts Renowned as a revolutionary figure in the realm of fieldwork, Malinowski contributions towards anthropological theory are also referenced in The Sexual Life of Savages. Malinowski is often credited with the advancement of the structural-functionalism school, and developed theories on the basis that the function of institutions was to satisfy biological needs (Barrett, 1996: p.65). Malinowski displayed many of the basic features of structural-functionalist theory in The Sexual Life of Savages, especially the emphasis on the study of society and social structure, the importance leant to kinship and the family, and the belief that society was in a state of equilibrium, with institutions steering society back to a state of harmony when disruption occurred (Barrett, 1996: 61). Malinowski depicts Trobriand society as harmonious, with these aforementioned disruptions easily countered by pre-existing cultural practices. 5 6 1.5 - Methods As previously stated, the research methods used by Malinowski represented a great change in the way anthropological fieldwork was carried out. Drawing inspiration from Franz Boas and his fieldwork in Mexico, Malinowski spent an extended period of time in the Trobriand Islands, immersing himself in Trobriand life. Learning the language and acquiring confidents among the Trobriand community contributed toward Malinowski’s understanding of the subject studied, as well as his participation in Trobriand village life. In essence, Malinowski’s emic approach contributed towards how his research was carried out, by crafting a narrative that speaks from the inside out. 1.6 - Main Data and Argument The main data that Malinowski gathered concerned the relationships and social constitutions that the Trobrianders subscribed to. Implementing the informants that he had gathered in the time he spent on the Trobriand Islands, Malinowski’s main argument was that sexuality and sexual exploits pervade Trobriand culture and society at many levels. However, sexuality remains one of many examples that Malinowski uses this as a number of examples to further his argument that Trobriand society functions in much the same way as western society, in that social institutions, such as the family unit and labour divisions, work to fulfil biological needs. In addition, Malinowski’s discussion of Trobriand sexuality and kinship seeks to reinforce the theory that the ‘savage’ was not irrational, but developed institutions that reinforced lineage patterns in much the same way as western society. For example, Malinowski discusses the fact that the biological father is not considered the father of the child, not through ignorance of the biology involved, but rather to reinforce the matrilineal model of Trobriand inheritance. 6 7 1.7 – Textual Composition The Sexual Life of Savages is composed as a compendium of Trobriand culture, detailing everything from the sacred to the mundane. Malinowski’s partial integration into Trobriand society allowed access to not only what was perceived as exotic, such as practices in magic and sacred rituals, but also allowed him to evaluate everyday village life and form relationships with community members. However, this particular ethnography is not set out in narrative form; there seems to be little time scale and reference to when in time events were observed or information was gleaned from informants. The text is set out in a number of chapters, all with sub chapters, detailing particular points of interest related to the subject of the monograph. Illustrations and photographs with short descriptions often accompany subjects of interest. Essentially, Malinowski crafts a work that attempts to comprehensively detail the lives of the Trobrianders, from birth until death, yet still providing information on what Malinowski deemed relevant, such as sexuality, kinship and gender roles, to fulfil his research objective. Discussion Malinowski plainly describes the focus of his study as the ‘sexual problem’ (Malinowski, 1928: p. 1). The research question arises from the attitudes towards sexuality in the era that the monograph was written; as Elizabeth Fee demonstrates in Sexual Politics of Victorian Social Anthropology, “Current social arrangements should be seen as the final culmination, the glorious end-product of man’s whole social, sexual, and moral evolution from savagery to civilization” (Fee, 1973, p. 24). Essentially, Malinowski’s research question is a product of his time; the dichotomy between civilized and savage was dissolving due to work on unitary theories such a structural-functionalism. The ‘sexual problem’ that Malinowski alludes to as part of his research question is a microcosm of the broader question of human understanding. Malinowski’s enquiry into the function of sex in Trobriand society was a thrust toward modern unifying 7 8 theories, with an explanation of the previously considered irrational nature of Trobriand sexual exploits just one of many contributions toward the structuralfunctionalist school. Thus, it can be argued that the research question is more than asking about the sexual lives of Trobrianders and how it infiltrates their culture and society, but also asks whether the Trobrianders follow institutions to maintain equilibrium and satisfy biological needs like any other society. The condition of the field at the time is also testament to the relevance of the research undertaken by Malinowski. The foundations for the prevalence of the British school of anthropology, characterized by the structural-functionalism school, were being laid due to the work of Malinowski, and previously Alfred Radcliffe-Brown. Malinowski’s loyalty to the structural-functionalist school is rarely referenced in The Sexual Life of Savages. There is no preamble from Malinowski concerning his theoretical inclinations, but prefers to reference his findings and reflections in the text itself. For example, when discussing the sources of love magic, Malinowski states ‘…This myth really accounts, not for the origin of love magic, but for it’s transfer from Kitava to Iwa. It’s most important cultural function, however, is that, being believed, it establishes a valid precedent for the efficiency of love magic’ (Malinowski, 1929: p. 545 – 546). Malinowski frequently references core components of the structural-functionalist theory, including the function of myths in society and how society maintains and promotes equilibrium. Malinowski seems to take his theoretical inclinations as a given in The Sexual Life of Savages, with little reference given to how he will evaluate the data he gathered. However, his evaluations are consistent throughout, and are in keeping with the structural-functionalist theory. The methodology used by Malinowski is explained in much the same way as his theoretical framework; description is few and far between. The time and place of research are not referenced specifically, and although the monograph reads chronologically, there is no explicit reference to dates and times of research. In addition, no map is provided by Malinowski, giving scant description to what he merely terms ‘a South Sea atoll’ (Malinowski, 1929, p. xxvi). 8 9 Malinowski’s presentation of his relationships and confidents is far more comprehensive. Although Malinowski does not detail every encounter with informants, perhaps due to the nature of his fieldwork and his immersion in Trobriand life, he does reference his conversations and interviews on a regular basis. For instance, Malinowski notes the ‘many times’ he would sit in the village in conversation with the chief (Malinowski, 1929, p. 33). It is arguable that it would be impractical for Malinowski to log and reference every conversation held with his informants, due to the extended nature of his fieldwork, but his references to conversations, meetings and observations do create a sense of his integration into Trobriand society. His reference to these conversations when relevant create the picture that he is reporting from the inside out; his notes seem trustworthy and well informed, due to his long standing relationship with the Trobrianders and his emic style of reporting. The question of whether Malinowski becomes a storyteller or remains an ethnographer can also come under scrutiny when analysing his presentation style in The Sexual Lives of Savages. In How to Read Ethnography, Pierre Bourdieu is quoted as stating, “…here in lies an important difference between the ethnographer and the novelist. Whereas a novelist will typically focus our attention on an individual, their struggles and motivations, a similar starting point will take the ethnographer in an abstract direction. From the immediate features of a life or lives, an anthropologist will extract key elements and use them to understand and generalize social aspects of seemingly individual capacities and motivations.’ (as cited in Gay y Blasco & Wardle, 2007, p.59). This statement is especially helpful in the analysis of Malinowski’s work. Despite his insistence on the ‘scientific treatment of the subject’ (Malinowski, 1928, p.xxiii), One can be forgiven for considering Malinowski as a story teller of non-fiction; the introduction of certain characters and their relationships with others and a narrative that does not work on a strict basis of hypothesis preceding evidence contribute to a non-scientific feel. However, as stated above by Pierre Bourdieu, it is the ethnographer’s job to use the ‘individual capacities and motivations’, and the lives of the subject, in order to identify common themes, laws and rules. Malinowski’s informal, flowing approach does not negate the fact that the 9 10 evidence gathered contributed toward Malinowski’s theories of societal equilibrium and the importance of kinship and family in pre-industrial societies (Barrett, 1996: p. 65). Another point of note that arises from How to Read Ethnography is the link between the author’s identity and the work they craft. The adage that One is a product of One’s own culture can be applied to how the ethnography is constructed, the data the ethnographer gathers, and the points of interest that the ethnographer identifies. Gay y Blasco and Wardle state that ‘because ethnographies are written by individuals who are socially and culturally situated and engaged, the context is always part of the text’s very fabric. We therefore argue that an awareness of this context will help the reader gain a greater understanding of an author’s standpoint and argument. For this reason, this awareness will also lead to a better appreciation of the lives of the people an ethnographer is trying to portray’ (Gay y Blasco & Wardle, 2007, p. 118). In essence, the goals and ambitions of what Malinowski aimed to achieve through the undertaking of this fieldwork and the writing of this ethnography can be far more clearly understood when discussing the context in which it was written. In an era where evolutionism was disintegrating rapidly, the anthropologist was beginning to rise from his armchair and set sail for the four corners of the globe, and the evaluative process of ethnocentrism was fast becoming out of fashion due to the work of Durkheim, Radcliffe-Brown and Malinowski himself create a context for which The Sexual Life of Savages was written. It allows the reader to appreciate how groundbreaking this ethnography was. Irving Astrachan notes in The Journal of Educational Sociology that The Sexual Life of Savages was ‘likely to become a standard reference work in its field’ (Astrachan, 1930, p. 318.319). The Sexual Life of Savages represents much more than the Trobriand Islanders and their way of life, but a significant shift in anthropology and beyond. Through resources such as Astrachan’s review and understanding of the era, a greater understanding of what Malinowski aimed to achieve can be reached. 10 11 Conclusion Even on face value, Malinowski’s ethnography The Sexual Life of Savages represents a significant achievement. Building on his previous research for Argonauts of the Western Pacific, Malinowski created a second volume that once again explained an unfamiliar culture through a theory of general laws and norms. In a work that covers every aspect of every Trobriand Islanders day, from the food they eat for breakfast, to the relationships held with family, members of different rank, children and members of a different sex, to the rituals that are observed, Malinowski manages to bring an intent and structure to a colorful depiction of island life. His work represents Trobriand culture as a whole; a rational people who seek to fulfill the same needs and wants as any other. For instance, the denial of biological paternity, as discussed previously in this review, is not irrational or contradictory, but seeks to reinforce the matrilineal line of descent. Customs and rules that may have been considered irrational, uncivilized or barbaric by an evolutionist were now being viewed by anthropologists as different building blocks in the same universal societal makeup, or different tools that build the same structure. This is what makes Malinowski’s work so remarkable. The work not only represents the Trobrianders on a cultural level, but also represents the field of anthropology at the time; the study of people that was beginning to strive for the answer to the question ‘what makes us human?’ In a wider context, The Sexual Life of Savages represents foundation stone of structural-functionalism, and the development of theories concerned with the function of societal institutions. It also represents a shift in the how data was collected to bring weight the hypotheses. Malinowski not only planted himself in Trobriand village life, but also became a ‘recognized friend’, according to Bernhard J. Stern in the journal Social Forces (Stern, 1930, p.469). In summary, Malinowski’s fieldwork approach represented more than a change in anthropology and how it was undertaken, but represented a change in attitudes in western society; many in the ‘civilized’ world were starting to learn that the ‘savage’ was no different from themselves in the biological and societal needs. This ethnography, therefore, is representative on 3 levels; of the Trobrianders themselves, on their way of life 11 12 and how sexuality is linked to all facets of Trobriand culture, secondly, a change in the study of people and the casting of the shackles of evolutionism and ethnocentrism, and thirdly, a change in minds of those who ever considered those people across the plains and oceans, and the start of a realization that when the culture is stripped away, the similarities between the Victorian Britain and the Trobriand Islander are remarkably stark. 12 13 Bibliography Astrachan, I. (1930). The Sexual Life of Savages: Review. Found in Journal of Education Psychology, Vol. 3, No. 5 (Jan., 1930). American Sociological Association. Barrett, S. (1996). Anthropology, a Student’s Guide to Theory and Method. University of Toronto Press. Fee, E. (1973). The Sexual Politics of Victorian Social Anthropology. Found in Feminist Studies, Vol. 1, No. 3/4, 1973. Feminist Studies, inc. Gay y Blasco & Wardle (2007). How to Read Ethnography. Routledge. Lewis, I (1976). Social Anthropology in Perspective. Cambridge University Press. Malinowski, B. (1929). The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia. New York: Eurgenics Publishing Company Stern, B. (1930) Are Savages Moral? Found in Social Forces, Vol. 8, No. 3 (March., 1930). Oxford University Press 13