Extreme-Confusion

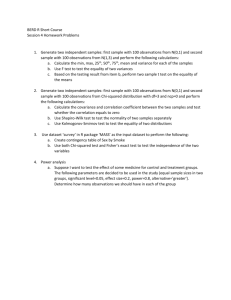

advertisement

Equality Ethics Excellence ‘Extreme’ confusion – a cause of indigestion? by Razia Aziz the Equality Academy Reading some of what has been in the media recently about the Birmingham schools ‘scandal’ (or the Government/OFSTED ‘scandal’, depending upon whose ‘side’ you happen to be on), it would seem that many reasonable people have become seriously detached from their capacity for reason. At some level, this is quite understandable – both terrorism and religious orthodoxy are emotive subjects, liable to give one a serious indigestion if discussed over dinner. But both are urgent and essential topics of our time, which have become obsessively associated with each other in the case of Islam - so we need to learn how to debate them with reason and compassion. At the Equality Academy, in our work on unconscious bias – which is now a foundation stone of our diversity training – one of the areas which our clients have found most useful is an understanding of how the unconscious mind creates ‘implicit associations’ when two things occur together over and over again in our awareness. For example, the gender of our school dinner ‘ladies’ can for a lifetime create an implicit association between the female gender and school food. This may be associated with a warm fuzzy feeling or a pain in the tummy, depending on our assessment of school meals – a feeling which is triggered again each time we enter a school dining hall and ‘smell that smell’. Implicit associations can be produced both through actual experience (as in the above example) or through related experience – through what we hear and see, for example in the media. They can be based on factual or inaccurate data. They are produced – and can affect our behaviour regardless of whether we consciously agree with them. One of the most unfortunate spin-offs of media preoccupation with the threat of ‘Islamist terrorism’ to ‘the Western way of life’ is the almost relentless creation of unconscious (implicit) associations in the minds of anyone who regularly accesses mainstream media between ‘Muslim’ and ‘Islam’ on the one hand, and ‘terrorism/ist’, ‘radicalisation’, ‘extremism’, ‘violence’ and ‘threat’ (to name but a few of the obvious ones) on the other. Those who were around in the 1970s can hear echoes of the similar associations made then in relation to Irish / Republican people. However, today, the media is far more ubiquitous, and news is instantaneous and 24/7, which only means implicit associations are built more quickly and reinforced more strongly. Just as with the school meals, there is an association between things that occur together – and how the implicit association makes us feel depends upon the emotions triggered by the way the association is experienced. The way the ©Equality Academy 2014 Razia Aziz tel: 07976 916250 e.mail: razia@theequalityacademy.com www.theequalityacademy.com Equality Ethics Excellence unconscious brain is wired, anything which seems to threaten our safety triggers parts of the brain associated with ‘fight and flight’ responses. Reason and compassion go out of the window in favour of survival. The very strong sense of threat which is conveyed by most of the prevalent information related to Islam and Muslims will therefore produce in most people a strong negative emotional association. This is something to which we are all susceptible, regardless of our conscious political viewpoint. In this environment, there is a real danger that the negative associations, connected as they are to our survival instincts, over-ride our more developed (but rather brittle) capacity for reason, and flood our minds with ‘fight’ and ‘flight’ messages which we find hard to resist. But resist them we must – if we are to develop a compassionate and realistic local approach to the growing threat to social cohesion which the global situation presents. In this vein, I would like to share some historical reflections. When I was at school in the 1970s, there were several same sex schools, including my own. Gender segregation was not outside of the norm. Girls did not wear trousers to school. We were not allowed to play football (the one time our games teacher let us play football, she made us swear not to tell the head teacher, who would have disciplined her). Girls did not do woodwork, or any practical mechanical science. Boys did not learn to cook, knit or sew. In co-ed schools, girls and boys had separate entrances. We did not learn about any religion apart from Christianity; we had to celebrate Christian festivals. If, like the Jewish and Muslim kids, you did not eat pork, you’d be lucky to get a chunk of cheddar cheese in place of sausages with your mash and gravy. Everyone learned Christmas carols. As a British girl of Indian Muslim origin, I certainly felt the weight of minority status in all of this – though, to my parents’ consternation, I loved singing Christmas carols! (I never told them I quite liked sausage rolls too – before I became a vegetarian). This was 1970s south London – not exactly your hotbed of religious extremism. And my point? Very simple: religious conservatism or orthodoxy is one thing. Political extremism and terrorism is another. To conflate the two – even to put them in the same sentence, risks triggering implicit associations which can stop us thinking rationally and compassionately. The combined failure of compassion and reason has the power to tear our society apart. What I described of my 1970s’ schooling was simply contemporary middle class Christian southern England exercising its norm. From a minority eye witness point of view these norms were neither benevolent nor acceptable – and many people worked to change them. But they were not ‘evil’, and my peers and family never ©Equality Academy 2014 Razia Aziz tel: 07976 916250 e.mail: razia@theequalityacademy.com www.theequalityacademy.com Equality Ethics Excellence viewed them as ‘religious extremism’ or ‘dangerous segregation’. My parents objected to me attending assembly and saying Christian prayers, but they did not think I was in danger of ‘radicalisation’ which would make me join the army to fight the cause of ‘the West’ or Christianity worldwide – they simply wanted me to preserve some flavour of my distinctive Indian Muslim heritage in the all-pervasive soup of post-Christian, post-imperial British culture. The norms of the 1970s now seem outdated and socially conservative, but not a threat to civilisation. They are not that different to the values expressed by the more conservative elements in several minority faith communities – Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, Rastafarian and yes, Christian. To point this out is not to be naïve, but to provide an important corrective to the current debate. The problem is that the words ‘extremism’ and ‘radicalisation’ are too often used in a way that is at best confused and at worst pernicious. Without careful definition they stoke up the fires of tension instead of cooling them, preventing the very dialogue we need to promote a vibrant and inclusive society. What we know about triggering unconscious bias is that to avoid it we have to be highly responsible in our use of language. Only then can we actually define and confront the corrosive thinking – whether related to violent extremism or unthinking prejudice against minorities – that really threatens to undermine our society. Only then can we build a broad consensus in favour of creative inter-dependence between very different kinds of people. If we want to illuminate instead of pontificate, we need a mindful language of engagement, which allows us to separate out unhelpful associations and clarify what we are really saying. So next time someone says ‘extremism’ or ‘radicalisation’ invite them to lunch. Be curious. Take the time to ask them exactly what they mean. Add a dash of common sense, a few counterfactuals and some actual facts, and you might just have a recipe for a meal that won’t give you indigestion. Oh, and a word on gender segregation, which is spoken about as if it is, in itself, evil. Many feminists would argue, and research would support them, that girls do better academically in gender segregated, than in co-educational, contexts: you only have to look at the fact that most of the country’s elite women scientists went to girls’ schools. The message: never take anything for granted, always read the label and separate out the ‘ingredients’. Happy dining! For tailored Equality, Diversity & Inclusion Leadership Training and Consultancy please contact us ©Equality Academy 2014 Razia Aziz tel: 07976 916250 e.mail: razia@theequalityacademy.com www.theequalityacademy.com