Dominican students in NH schools

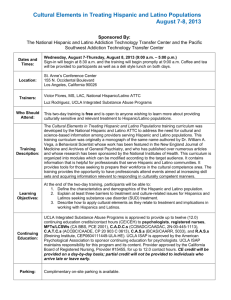

advertisement

Dominican Stereotypes in Little Mexico: Latino Students in New Hampshire Schools Almost without exception, if you talk to someone who went to Central High School in Manchester, NH, one of the first things they will tell you is that Central is the most diverse high school in the state. This is usually followed by something about the number of languages spoken there. While the two high schools in Nashua, North and South, might not claim to be the most diverse, people who attend them and work in them consider them to be diverse, urban schools. This is a rarity in New Hampshire, which has traditionally been an overwhelmingly white, rural state. But what do people mean when they tell you these schools are diverse? What does diversity mean on a day-to-day basis for the people who inhabit those schools? How do they experience diversity or the integration of different racial and ethnic groups? I came to this question from an interesting position. While I am a native of New Hampshire and attended a public (entirely white) regional high school in southern New Hampshire myself, I have spent a large part of my adult life in the Dominican Republic. I was married to a Dominican and my three children identify as Dominican, so I have seen this issue from many vantage points. One thing that has always puzzled and troubled me is the disconnect I see between my experience with Dominican people in Santo Domingo and the images and stereotypes of Dominican people, and particularly Dominican students, here in the United States. While the people I knew were hard-working, with high aspirations for their futures, the typical image of a “Dominican-York” was of a shiftless person who dealt drugs and was involved in crime. This image of Dominican-Americans pertains even on the island itself, or perhaps especially there. I decided to try to investigate what the actual experience of Dominican students in New Hampshire schools was like. Abby Hoffman, a radical leader of the 60s, on a visit to New Hampshire at that time, referred to it as “the vanilla state.” This was the New Hampshire I grew up in. As recently as 2002, the student population was 95% White non-Hispanic, according to the NH State Department of Education figures. In 2012, that number had dipped below 90%. In the two most urban districts in the state, the figure has dropped below 66%. While this is still a large proportion of white students, the change has been dramatic and rapid. The fastest growing segment of the population of students of color is the Hispanic or Latino group, which now approaches 20% of the school-age population in these urban districts ("Attendance and Enrollment Reports"). New Hampshire is part of a pattern of secondary migration for Hispanics (Lichter and Johnson 499). Most are Puerto Rican or Dominican and many have migrated from Dominican settlements in New York City to Lowell, Massachusetts and on to Manchester and Nashua (Vasquez). If past patterns hold, this trend will not only continue, but escalate (Vasquez). Some Dominican and Puerto Rican families are settling outside of these urban centers and their experience is quite different (Camayd-Freixas, Karush, and Lejter 1-17). I decided to focus this preliminary investigation on urban high schools in Manchester and Nashua where larger numbers of Latino students attend school. Prospects for Latino students in New Hampshire are not encouraging. Far fewer of them attend four-year colleges than their White counterparts. Hispanic males are the group least likely to pursue higher education here in New Hampshire, which corresponds to the national figures ("Latino College Completion: New Hampshire"). Outside of New Hampshire, some of the beliefs that act as barriers to the academic achievement of Latino students in the country include the tendency to label Latino students as behavior problems, problems with white teachers understanding Latino culture and the belief that Latino parents do not push their children to work hard (Becerra 167-177). Diminished views of Latino parents’ homelife by white teachers were also cited as barriers to achievement for these students by Delgado Gaitan (305). As part of the series on immigration in New Hampshire, New Hampshire Public Radio documented racial tensions and difficulties for Latino Students at Nashua High School South (EvansBrown). A series of articles in the Nashua Telegraph looked at the debate over tracking or leveling in the city’s schools (Trivilino, Brindley). There has been little scholarly attention to documenting the demographic shift in these schools and how this is affecting students and teachers. For this investigation, I visited both high schools in Nashua and spoke with students and teachers. I conducted several individual interviews: two with Dominican female students, one from Central High School and one from Nashua High School South. I conversed with two sections of a Human Relations class at Nashua High School South, reviewed student produced videos from Nashua South and from PSU, recorded a conversation about race with a group of Manchester middle school teachers and interviewed a young teacher who is currently a regular substitute teacher at Nashua High School North where she completed her student teaching as well. While this is by no means an exhaustive investigation, clear patterns did emerge which suggest the broad outlines of what it means to attend or work in “a diverse school” in one of New Hampshire’s southern urban centers. First Lessons Perhaps because of my own experience moving between languages and cultures and crossing international borders, I had thought about the differences between the Latino and other students in New Hampshire terms of culture and language. I had even framed a question which referred to “native NH students. “ The students I spoke with framed these differences entirely in terms of race. Every student I talked to referred to “white kids” and, variously, “Spanish kids” or “Hispanic kids”. They rarely used the word “Latino.” For them, being Hispanic was more a matter of race than ethnicity. This may in part stem from the fact that the Latino population is comprised of darker-skinned Dominican and Puerto Rican students. Teachers were more circumspect. They generally avoided naming race if possible, and did so with some discomfort. While were hesitant to name races, they did refer to “minority kids.” They evidenced insecurity about how they named the different groups of students. Laura, for example, who is currently substituting at Nashua North, noted, “Sometimes I see the minority kids walking and talking with the honors white kids” (online interview). She then quickly clarified, “I’m sorry if I’m not saying this politically correct, I’m not sure how I should be distinguishing the types of kids.” Her hesitancy, which I noticed with other teachers as well, indicated to me that they are not accustomed to discussing the racial divides in their classes in these terms. Race and Tracking Rather than framing the issues in terms of race, teachers were more likely to talk about levels. This reflects the fact that even in the most demographically integrated schools, classes are “leveled” through the tracking system, and tend to be segregated by race. This was obvious to me when observing in Nashua High School North, particularly when an entirely white AP class exited the room to make way for an overwhelmingly dark skinned “foundations” (lower level) class. The racial segregation in the levels of classes was obvious to every student I interviewed, and they all commented on it without being specifically asked about it. Teachers, however, are much less apt to talk about this division, although when I ask them directly, they will acknowledge that it exists. As Laura puts it, “I am sure they’re aware of the racial aspect of it, but they mostly seem to be annoyed about the tracking system on an academic level. “ Many teachers seem surprised when they read about racial issues in schools. A middle school science teacher from Manchester noted, “I don’t necessarily see it as much as other people, because I read a few articles and I was just flabbergasted that wow, these things happened” (Manchester teachers discussion). Another teacher in that discussion added, “Some of what we’ve been reading I find it hard to believe that kids of color are actually being discriminated against in our schools and in our classrooms here in Manchester, because I don’t really see color so I’m not looking for it.” It is common for white teachers to assert that they “do not see color.” Bonilla-Silva refers to this as “colorblind racism.” Whites deny that they are aware of color because they feel that to acknowledge that they perceive even obvious differences in skin tone would be racist in and of itself. Despite teachers’ hesitancy to acknowledge race or racism, students clearly feel the effects of racial stereotyping and negative perceptions. In a discussion with a human relations class at Nashua High School South, a Dominican student reported witnessing instances of outright racism in her foundations level classes. Teachers were said to “tell students to go back where they came from” (NHSS Human Relations discussion). I saw many nods of assent in this group of more than 20 students and no one indicated disbelief. A white student in the class reported how rules were enforced differentially and how she could be walking down the hall doing exactly the same thing as the Latina student beside her and the teacher on duty would reprimand only the other student. There was widespread agreement within the groups of students I spoke with about these things. All students in these classes acknowledged them, no matter their racial group. While I don’t believe these overt racist attacks are common, teachers clearly feel frustrated working with lower level classes. Laura reports, “It seems like they get frustrated and struggle with the same things I did during my student teaching. They need to teach Beowulf to a group of kids who are writing on a 5th grade level, and also (not always), but I’ve noticed that the teachers sometimes sound like they don’t feel like they’re getting support.” Most of these complaints are about their foundations classes. As Laura says, “I wouldn't say they're annoyed at the kids in foundations individually. I think they feel like they're given these students who can barely write, and they were trained for secondary school, and they feel unprepared to teach foundational/basic writing/material, and then administration keeps saying they need to teach certain things and be friendly with the students.” She adds, “This is just what I’ve guessed at from conversations I’ve had. No one's specifically told me this to my face. They’ve hinted at it though.” Because of the segregation in these urban high schools, their frustrations with lower level classes can take on a racially charged tone. “Little Mexico” One problem is that white students and teachers have very little background or understanding of the various Latino cultures represented in their schools, and tend to view the Hispanic students as one big undifferentiated Spanish-speaking mass. The students I spoke with at Nashua High School South reported that there is an area in the hallway referred to as “Little Mexico,” even though the Latino students at Nashua are mainly from Ecuador, the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. These subgroups occupy clearly delineated areas of that corridor, but these differences are invisible to white students and most teachers. Angela Mendez, a Dominican student who graduated last year from Central High School, speaks to this issue. “The thing that upsets me the most is when everyone thinks that [in] the Spanish culture that everything’s Mexican. Nothing in the world makes me more upset because they don’t even realize that the only thing that Dominicans and Mexicans have in common is speaking Spanish, and not even, because the Spanish is completely different” (personal interview). She goes on to say, “Every single country has its own individual culture and individual things that make it unique so people shouldn’t generalize it as a whole. The same way in Europe – every country has its own thing—and even here in the United States where everyone speaks English, but you go to different parts and it’s all different.” These differences are rooted in the different histories of the countries, and these histories of hostility between Latin American groups can carry over to the hallways of New Hampshire high schools. A group of students at Nashua South described the situation in their high school by saying there are three main Latino groups in the school: Puerto Rican, Dominican and Ecuadorian. Each has its own area in the main hallway outside the main office where they gather between classes. These areas are well defined. There is a much larger division between Hispanic and White students. White students complained about having to pass through this hallway area, which was so tightly packed that sometimes they had trouble getting through and were “harassed for pushing.” They noted it was a high traffic area that they would often have to pass through to get to class. All students described fights, which often involved boyfriend/girlfriend issues, but then escalated because “you can’t just have a fight between individuals of different groups without the whole group getting involved.” One student said you can’t “just fight with one without it becoming five or six on each side.” Despite the clear delineations in the hallways, teachers seemed almost reluctant to recognize these differences, as if to notice them would somehow be racist. Laura reports that she referred to a student in her block three class one day, and another student answered by asking if she meant “the Brazilian one.” Laura was uncomfortable. She says, “I don’t think they were being mean about it. It was just another way to classify someone, although I have heard that some of the Dominican kids don’t like a lot of the Puerto Rican kids. I don't mean that to sound bad, but I’ve just noticed that.” In Laura’s response, again she seems to equate noticing these differences with “sounding bad” or “being mean,” even though she is making no derogatory insinuations in her observations. Back in Track: In the Classrooms Within their classes, the tracks in all of the urban high schools have clear racial delineations, with the upper tracks being mainly white students, a mix in the middle, and the lower tracks being mainly students of color. Although with the percentage of white students in these schools still so high, there can be considerable mixing in both the middle and lower tracks. Interracial relations are nominally better in the upper classes. Laura notes that she sometimes sees the few Hispanic students from her honors classes walking through the halls with white students. Angela Mendez was one of those few Hispanic students in the upper tracks. She says, “I was always a smart girl, so I was always in level 4 classes, and with the school system of course those are going to be the better classes, the better teachers and so forth so I always always really liked all my classes, all my teachers and the people I was surrounded by. ..I think that’s why I say I loved all my teachers. I don’t think they saw me any differently than any other student. I was just a normal student.” When Angela says that the teachers in her honors classes viewed her as just a normal student, it is clear that normal for them meant white. She reports that all of her high school friends were white and she had trouble answering questions about other Latinos at Central High School, because she said she didn’t hang out with them. She says there was only one other Latina student in her honors classes. “It was just me and her all four years of high school in those classes.” Angela admits that sometimes it could be hard: “There are a lot of stereotypes … like oh, what’s this person doing in there? They’re shocked to see you in higher level classes.” She goes on to say, “Even the Spanish people are looking down on you like look at this one, esa gringa, with all the white people privando blah blah blah.” She admits that she faced some challenges: “Most of my friends are white and going to their houses, they will tell me oh, by the way, my dad, he doesn’t like Spanish people or whatever so you feel uncomfortable.” Angela began to define herself in opposition to “Dominican stereotypes.” She says, “In high school I got the stereotype of oh, she’s Dominican so by the time she’s 16, she’s gonna be knocked up. I feel like that’s why I worked so hard in high school because I didn’t want to be another one of those Hispanic stereotypes. I wanted to graduate, go to college get a degree, not get pregnant. And it’s hard fighting against those stereotypes but when you do it, it makes you feel so much better about yourself.” Angela does not consider that in defining herself in opposition to the stereotypes, she reinforces those stereotypes by trying to be seen as “not Dominican,” or by defining Dominicans as the stereotype she envisions. Many Latino students, when given the opportunity to take honors classes, choose to move the middle levels instead. One such student at Nashua South explains, “I would rather be in the extensions classes because in honors everyone does their homework and in extensions it’s more relaxed, and I would rather be the one giving help sometimes than always be the one receiving it.” Despite this student’s better ability to move between groups, he prefers to keep to the middle. I asked Sofia, another Dominican student at Nashua South whether she would consider taking honors classes. Despite the fact that Sofia is completely bilingual and was articulate and self-assured in her human relations class, she seemed uncomfortable with the question. She replied finally that she might do it if it were a class she was really good at, but when I asked her, she could not think of what that might be (personal interview). Another Latina student at Nashua South said that she would not want to be in an honors class because she would “feel like a nerd and people would think I was trying to be white.” Despite all of these barriers, upper track students credit themselves alone with their placements, and lower track students blame themselves for being lazy. Although Lisa Yates, the human relations teacher at Nashua South, told her class that the tracks did not represent any real differences in abilities, (and she is a teacher who has clearly won students’ trust) they plainly did not believe her. Students were counseled into their levels based on teacher recommendations in middle school. and found them very hard to break out of. Several students at Nashua South reported that they had either been moved down or discouraged from taking harder classes. While it was possible to advocate for themselves and move up levels and take more challenging classes, they were often discouraged from doing so by guidance counselors. Despite their awareness of the racial segregation in the tracking system, they still tended to equate the tracks with the level of effort. The “lower track” students seem to have accepted the school’s implied view of their limited potential. They blamed themselves for not being in higher tracks, calling themselves lazy. Given the racialized composition of the tracked classes, it is easy for everyone involved to make the leap to concluding that students of color are lazier than white students and don’t care as much about their future. This hidden curriculum lurked just below the surface in all of my conversations with students. Life in the lower tracks is not easy. Both students and teachers report a lot of hostility between groups. Because New Hampshire’s urban high schools are still almost 2/3 white, there is considerably more of a racial mix in the lowest level classes, where the lower SES white students are grouped with the students of color. Although Laura reports that some foundations classes are comprised almost entirely of students of color: “I have had only one white student and the rest are various minorities who all got along, and the white kid sat by himself … one class in particular that I’m thinking about there was one white kid and … the minority students sat around in the circle and the white kid sat by himself.” Even where the mix is more even, there is a lot of tension. Laura reports, “I don’t think they hang out with each other at all. At least in my foundations class, [the two groups] seemed to really not like each other.” One of Laura’s reflections during her student teaching describes the kind of situation that can arise in a foundations class: “It escalated some more on Tuesday. My unit is on Macbeth, and my students, in general, are heartily resisting it. Not all of them, but probably about half the class. So we were talking about James I and his obsession with the torture of witches, and how that might have served as a reflection for the treatment of women during this time. It was actually going good for most of the class—most of them were appropriately disgusted and indignant with some of the facts about the everyday lives of women during Shakespeare’s time—until one of my students said, “This could never happen today.” Thinking he wanted to engage in the discussion, I jumped on board and pointed out that it was the king who was heading the witch hunts (I was thinking of steering the discussion into a theme of power, and then maybe going into modern day instances where leaders of countries abused their power and killed people—like Hitler or something). Then this student decided to somehow change the conversation to immigration. I don’t know how he made that leap, but he did, and then hell broke loose. About half this class is made up of of first or second generation students who are ELL. “So his little group was having a conversation about immigrants and how they work lousy jobs and basically are stuck there forever because white people keep them downtrodden (in any other class this would sound like a thought-provoking discussion on fairness and power in society, but here it was a thinly veiled jab at the other group about their future prospects). The other group responded predictably through the use of angry words and tone of voice. I, floundering at this point, and thinking I could miraculously lessen the situation, said something like “this country was built on immigrants.” A few students started talking about where in Europe their family came from. Everyone was talking over each other at this point. I heard a student make a comment to the effect that they were all from European backgrounds where white people come from (I forget his exact phrasing as he kind of mumbled it to the person next to him). However, he didn’t say it quietly enough so that the other group didn’t hear him, and one of the students from the Hispanic group called him “Shrek” (like the ogre, if he had said this in another circumstance not in the classroom to a student, then I would have laughed). Everything got quiet after that, and fearing that it would turn into a “you’re so ugly…” contest, I told them that that was all I had for the day, and that they could talk quietly for the last 10 minutes of class.” We might not expect a student teacher to be able to lead students through the kind of discussion that this incident could have provided the opportunity for the class to engage in. However, there was an opportunity there when some of the tensions below the surface erupted into something that might be discussed in the classroom. When the student commented that “This could never happen today,” the discussion might have been moved towards examples of injustices in our world today, which students might then relate back to the text. However, this was not the stance that Laura’s cooperating teacher advised. She wrote, “My co-op and I have been working on strategies to prevent stuff like this from happening again. We talked to them about respect, our expectations, and everything, and informed them that we will have a zero tolerance policy from now on, and that we will start writing people up if we have to.” In fairness, these situations can be quite tense and teachers may be reluctant to confront them. Curricular Issues Laura says that teachers find their foundations classes difficult: “I think they tend to enjoy their other classes more. I don’t think they're trying to be unfair or cruel or anything. I think it makes them tired to be honest. They have a degree and they know all the fun stuff in English or whatever class they teach, but they’re stuck teaching the basics AND the advanced stuff. It’s like they need to do two things at once.” She also notes that, “The department heads need to make sure they follow curriculum, but it's hard when students aren't prepared to read or learn the things that the district tells them they have to.” The curriculum can be a barrier. English classes at both Nashua high schools follow a very traditional curriculum in all of the levels of classes. The normal “Beowulf to Virginia Woolf” survey of British literature is standard 12th grade fare. Despite their evident frustrations, there is resistance to change. In another of her student teaching reflections, Laura reports on a meeting she attended with teachers from both Nashua high schools to discuss curriculum changes. She writes, “Some teachers said that the push to include a more diverse curriculum was too political, and seemed to be afraid that in the rush to include diverse texts, the quality of the texts would suffer.” There seemed to be an unstated assumption that including texts by authors of color would reduce the quality. She goes on to write: “Others argued that since these texts had been established and recognized as having certain literary devices that could be taught in them, why should we teach a book that might not have the same level of presentation of literary devices?... [for example,] even though it is universally disliked, The Scarlet Letter has clear and definite instances of symbolism, and is therefore an ideal text to be used to teach symbolism vs. a text that might have superficial symbolism.” Again, the implication being that in texts by authors of color, the symbolism might be more “superficial.” The pressure to cover this traditional curriculum, especially in the lower level classes where many students are less prepared to read it, creates frustrations and problems for teachers, especially those who might not be as skilled at relating this curriculum to their students’ lives. Lunchtime The segregation that is evident in the classrooms extends beyond them as well. Students at Nashua South could describe exactly who sits where in their lunchroom. There are defined groups, mainly racially based, but also including such designations as “special education” and “freshmen.” One student reported that her sister told her where to sit when she came to the school. Another said that his brother told him where to sit, so it would appear that these places get handed down over the years. Lisa Yates added that any freshman could give you the map of the cafeteria by the end of the first week, although these things are rarely discussed explicitly. Lisa Yates tried to institute a “Mix it Up at Lunch” program sponsored by The Southern Poverty Law Center and Teaching Tolerance magazine. She ran into many obstacles. She writes, “…of particular interest to me is that there is very little faculty/staff support for this idea. I got Subway to cater it for three years… I offered it in another room because the culture of cafeteria tables was too strong to change. There were three teachers that supported the practice and several administrators and our principal did support it. Students reported that they only went for the "free lunch from Subway" and though the activities were fun, it did not change the culture of the lunchroom and encourage them to try to change lunch tables and meet new people” (email correspondence). These divisions are entrenched. Outside of Class Outside of class there are spaces in the hallways designated for certain groups such as “Little Mexico” at Nashua South. As Laura puts it, “the races are the cliques,” and as Angela says, “you tend to hang out with who you go to class with,” so all of her friends were white. Angela was not able to talk about the divisions within the Latino community at Central except in an abstract way because she did not associate with Latino students. As she put it, “I wouldn’t know exactly because I wasn’t part of that group but I would assume [it broke down by national origin] because within the Spanish culture in general, it’s very broken down.” Laura reports that when she worked with the drama program, most of the students were white, but she thought there were some Hispanic students on the soccer team. She noted though that they would divide themselves even on these teams, into Hispanic and White “jocks.” I asked Angela if she felt more identified with white people. She said, “It’s not even that I identify myself with them… I was part of … all my friends were white. All my friends. I did not have one Spanish friend and like I said within the white people you have the jocks, the cheerleaders and the preps and stuff. I was part of that group that we were the top ten of our class, always in the level four. You want to call us nerds we were nerds. That’s the group I identified with.” She assumes that other Hispanic students knew she was Spanish: “…with that last name every single Spanish person knew that I was Spanish. So I know that they must have talked so many bad things about me trying to be white, but I don’t care. I never saw them and even if I did I didn’t interact with them.” Angela acknowledges that her placement in honors classes may have had racial overtones. Unlike most Dominicans, Angela is very light skinned. She says, “For the most part, [Dominicans] are dark, so you see me with my light skin and my [straight] hair, even though you put me next to a white person and I don’t look [white] unless it’s winter [laughs].” She goes on to compare herself to other Hispanic students in other ways: “But that on top of [that, it’s] how articulate I was. I wasn’t speaking with the slang or the Spanish accent in comparison with them, and how studious I was – it was too easy for them to torment me. It was always me, I’m trying to be white, I’m trying to be white. You’re such a nerd. Yeah.” She seems to imagine other Hispanic students rejecting her even though she admits to having almost no contact with them. She describes herself in opposition to them: “The Spanish girls at my school were the stereotypical Spanish girls and I was the exact opposite of that.” She adds, “ So that was a little frustrating in the beginning but at the same time I didn’t care because I always had it in my mind that I am not going to be another Dominican stereotype, I am going to go for it for my future do well etc. etc… I understand because I am going to say 97% of the Dominicans who were at my school they were not first generation, they were born in the DR and they straight immigrants, barely spoke English so they were all in ELL programs so I am seeing where the school went you can’t go from ELL to an AP class.” Separating herself from other “Spanish girls” seemed to provide insurance that she would be successful in life. She even reported that one of her friends wrote her college essay about Angela and her desire to overcome her Dominicanness: “she wrote about how I am the person who inspired her the most and one of the things she wrote in the essay was “Angela inspires me in just her aspirations for her future. Time and time again she repeats to me, ‘Christina, I don’t want to be another Dominican stereotype. Christina, I don’t want to be pregnant when I’m 16. Christina, I want to graduate. I want to go to college.” Angela seems to feel that her desire to go to college sets her apart from other Dominicans, yet every Dominican or Latino student I talked to had such goals for themselves. Nothing to me seems more Dominican than believing in a better future and wanting to achieve success. Sofia, who languishes in foundations classes at Nashua South, told me she planned to go to Bunker Hill Community College next year to study nursing, but also thinks about going back to Santo Domingo and teaching English. Her parents have always stressed that they want her to be a professional. Students in Lisa Yates’s Human Relations classes also spoke of aspirations for further schooling beyond high school. In contrast, teachers tended to view their foundations students differently. Laura said, “Well, some of them will go on to Nashua Community College. But I think most teachers expect them to graduate from high school and that’s it. Some probably think their students will end up in jail. One teacher took his criminal justice class to the Nashua jail on a field trip. He said that it would be a field trip for some, and a wakeup call for others.” Perhaps worried about how that would sound, she added, “I don’t think he meant to sound like he was discriminating or anything.” Laura went on to say that “some will end up at legit colleges…but I think it’s rare,” implying that community college is not a legitimate option. Students tended to get classified early (tracking in both Nashua and Manchester begins in middle school) and it is very hard to move socially outside of your racial or ethnic group. Angela notes that if you start in ELL, you are finished. “I feel like the minute you start in ESL [classes], you’re done for. Even though English is my second language you are not going to put someone who is in ESL in AP English.” Some students do cross between groups, mainly the Latinos in the upper tracks. But as we have seen with Angela, this comes at the price of alienation from their ethnic group. Some whites do try to hang out with the Latino students, but they are perceived to be trying to “act ghetto” and are branded as “posers.” Lisa Yates pointed out to her class that students assumed these white students were “posing” as “ghetto” without really knowing anything about their lives or what part of the city they came from. There are a few outliers who do these cross racial lines, but this is difficult and they are subject to social pressure. José, a Puerto Rican student in Yates’s class, noted that he “took some crap from his friends and his brother” for mixing with whites. Interestingly, it was clear he meant his Latino friends who seemed to be his home base. José was a rare student who maintained close ties with both racial groups and tried to occupy an intermediate position. Lisa Yates notes, “I think that there is a sense of loneliness for students who have ties to many groups - José is a case in point in my mind. I think he feels comfortable in "both" groups, but I also think that it's a lonely stance to have a foot in two (or more) worlds.” All of the students I spoke with at Nashua South acknowledged that it was hard to move between groups, that they feared they would be rejected, that it took courage. They talked about being afraid to be the first to do so, and how it was hard to get that started. Yet they clearly had achieved strong and honest relationships across groups in their Human Relations class. Human Relations: Lisa Yates was seen by her students as being different from other teachers, partly because she knew so much more about them, as well as because of the more informal way she runs the class. Students reported that other teachers did not give them breaks because they did not understand their situations. Students reported that most teachers only cared about their material and were not interested in students’ lives. Perhaps much of this had to do with the rush to cover several centuries of British literature, for example. Teachers were aware, however, that students in their foundations classes were dealing with life issues that impeded their learning. Laura comments, “I had students in foundations class always saying that they couldn’t wait for lunch, and a teacher told me that one of the students only ate at school and that she sometimes gave him a dollar so he could eat more. I notice that foundations kids made a lot of jokes at their own expense about welfare.” She recognizes that lots of factors affect what goes on in her classes: “So much depends on the mood that these students are in during class. They all seem to have problems in their lives (one girl’s mom was arrested—the student is happy about it—and now she’s living with her brother and his wife and child, and they don’t want her there), but problems that make Macbeth seem like a waste of time.” Yates is freer to devise her own curriculum, and she devotes the bulk of her human relations class to, well, human relations. She states that they do “ice-breakers on steroids,” and they come to know each other as people. This was evident to me in my visit to her classes at the end of the semester. They were open with each other, made eye contact, were quite comfortable talking with me about racial issues in a class that reflected the demographic make-up of the school. Sofia talked about how important these Ice breakers were to her. She said she used to be a quiet girl before this human relations class. She got assigned to it, but she had heard good things about Ms. Yates, so she was happy about the assignment. She described the impact of the ice breakers, particularly an activity they did called “crossing the line” where Yates would read things like “who has thought about suicide?” and students would step forward if they wanted to say yes. She described the courage it took for her to step forward. “Taking a deep breath and making the leap to say something about myself which was true.” When I asked her, she acknowledged that learning about some of the things others had gone through surprised her, that people she would not have suspected had suffered so much. Students spend the semester doing projects like devising an anti-bullying curriculum to present at one of the middle schools, because, as Yates told me, “if they can teach it, they have to learn it themselves.” They created final projects that were poignant tributes to how they kept on going despite all of the difficulties in their lives. When I spoke with the Human Relations classes, they talked about the effect of knowing so much about each other-- seeing each other as individuals, and how it broke down the stereotypes and judgments which would have otherwise been present in the group. I was also aware, however, of how fragile this connection they have forged is and how their group identities linger beneath the surface. I noticed this fragile peace starting to fray at the edges when Yates asked them about the tracking system. They began to invoke stereotypes such as how foundations kids are lazy or honors kids are smarter, until Yates called their attention to it. Yates herself notes that she struggles to have them bring what they have learned in her class to the lunchroom or the hallways. Her first block class told me, even after a semester of this work, that human relations class was different and “things are never going to change in the school as a whole.” Yates asked the students how it might work if they were to do these kinds of ice-breaking exercises in other classes. One group didn’t seem to think it would work, but the other was more optimistic. One particular student was very vocal about this, saying he thought it would be a good idea and would change the school. There was some agreement on this in the group. José suggested that they do these kinds of activities in all of classes, at least at the beginning. I asked Angela what advice she would give to future teachers, and she said, ”Don’t assume that Spanish students know less. Don’t make that assumption ‘cause you’ll be surprised.” The students in Lisa Yates’s human relations class advised teachers to get to know their students and what was going on in their lives so they could understand why they did the things they did. Epiphanies and Final Thoughts The situation for Latino students in New Hampshire’s urban high schools is exacting an incredible human cost right now. I would be so bold as to say that there is no equity in these schools, and students’ lives are being affected every day. One thing I realized after my first few minutes of speaking with Lisa Yates’s human relations class was that any possible solution has to involve all of the students in a school. I originally planned to speak only to Dominican students, but I would not have had anywhere near as full a picture without speaking to all of the students in Yates’s class. It would be a mistake to assume that only students of color were being harmed by the current situation in these urban schools. All students are absorbing a hidden curriculum that teaches them that some lives are more valuable than others. This work is not easy. The first step towards beginning to work towards equity in these urban schools would be to see the inequity that exists here and now. Teachers need to have the courage to admit their own ignorance. All of us, no matter what our backgrounds, have to acknowledge that we have things to learn from each other. A middle school science teacher from Manchester described this feeling: “I feel ignorant sometimes. I do, I do, I really do. I feel like I am, and um, you know ignorance can be a nice place to be sometimes, but also I don’t want to be an ignorant person, I want to keep learning and I think [racism] is a really powerful topic. Obviously I think most of us have been stumped here with our discussion.” Another Manchester middle school teacher, who had been shocked to learn about racism in her own school system, reflected, “I think I always tend to wonder how I can be better at what I do. That’s part of who I am … I think my perceptions might be skewed by my background and so this learning is good for me because it will help me to be better able to recognize the subtle racism that does occur and make some positive changes … in myself, although I don’t like to think of myself as being racist.” For those of us who grew up in white middle class families, especially in New Hampshire, it would be astounding if we had not absorbed some of the racism of our society, which Beverly Tatum likens to “smog” that we all breathe in. Even students with a strong foundation in social justice teaching, as Laura had, find that their own backgrounds leave them unprepared, even when opportunities arise within the established curriculum. In another of her student teaching reflections, Laura writes: “This week I was talking about the Feudal System during the Middle Ages for a unit on The Canterbury Tales, and I was explaining how being a peasant during the Middle Ages was really difficult and harsh. I don’t recall how exactly how the conversation went down, but I said something like, “if you were born a peasant, there wasn’t much room for you to improve your situation.” My more outspoken students immediately started saying how they wouldn’t let that happen and how they would have challenged the system. So I responded that people didn’t really think about revolting (until the later Middle Ages), because they accepted that that was how things were, and how peasants were purposely kept downtrodden and had no means of defense if they challenged their liege lords. We talked more about this for a while, and then I said it wasn’t like today where we have this ideology where we believed that if someone worked hard enough they could accomplish anything. I knew that they had read The Great Gatsby last year, and I was honestly thinking about the American Dream (because even though everyone knows it’s a false idea, we still believe in it on some level). But then I heard one of my students kind of jokingly/skeptically say to the girl next to her[we know] how well that works out like that in real life. It took me about two seconds after she said that to realize that this would be an awesome time to pull out some sweet Social Justice, English-y discussion stuff because the student who had expressed skepticism was Hispanic (and I also have a diverse group of students in my class anyway). Then it took me half a second after that to realize that I was totally unprepared to change gears from my lesson at a moment’s notice. Then I realized that even if I could shift gears on-the-spot, I felt really unqualified to talk about those issues. Because, truthfully, I have never experienced any kind of hardship of that nature. There was never any question about me not going to college, my parents have been super supportive of me, and I haven’t really ever wanted for anything. I also realized that I take things for granted that I should be thankful for.” The way this student teacher skillfully related the curriculum to the issues students face was rare and wonderful. Yet even though she was highly skilled at integrating these issues into the curriculum, and even though she had talked about these issues in her teacher preparation program, she felt ill-equipped to manage the discussion because of her background. She continues in her student teaching to marvel at such opportunities, and she is getting a bit better at seizing them. She tells me, “I’m long-term subbing for a few weeks in a history class, and I’ve been teaching Reconstruction after the Civil War. We just did the Jim Crow Laws and segregation, and most of the students (I have three classes with 30 students in each of them, one extension level and two honors) seemed surprised when I told them about de facto segregation.” In this instance, Laura was able to appreciate the irony and share it with her classes. Part of seeing our students as individuals, and being able to seize these opportunities in the classroom is being comfortable with our own identities and comfortable learning from our students. Another part is knowing something about our students’ lives and the way they see themselves. Yates had clearly created an interracial, inter-level community with a mix of socio-economic levels in her Human Relations class. She subverts the tracking system by asking all of her students to take the class for honors credit. She explains, “Honors runs concurrently with the non-leveled class. I encourage all students to sign up for honors but unfortunately it does not help with their weighted GPA since this is not a “core” class (core classes are English, math, science and history).” But despite all of her efforts and her impressive successes, this community she creates, even by the end of the semester, is fragile. She lamented that students don’t transfer the lessons learned in her class outside of school: “One point of interest to me [in our discussion] was when white students (two females) noted that they had Hispanic friends in classes, but would not hang out or stand with them in the halls in between classes. (This kills me because I so hope that the lessons that they practice in my class do not seem to transfer into the milieu of the hall, life...)” Laura also notes that sometimes “there are a few Hispanic kids in my foundations class that I say hi to when I see them, and if I’m subbing they'll stop by between classes before the bell rings to talk to me, but they never come in when I’m in an honors class, and I’ve met their eyes as they walk by [but they don’t acknowledge me].” It should be noted that Lisa Yates creates her impressive community without also having to teach The Canterbury Tales or differential equations, and clearly these students, all of them, need strong academic preparation in core subjects as well. Yet I question how they will get that kind of preparation if these urban schools don’t address these underlying tensions and issues. Maybe we could all use a course in human relations. Implications: Obviously, this is a very preliminary study based on a small amount of data, but the consistency in these findings from disparate sources suggests that we can tentatively think about implications. Classes like Human Relations, while enormously valuable, can only accomplish so much. Working with the students alone will not be sufficient. We need teacher preparation that addresses these issues, and frankly, some of those of us who prepare teachers don’t have that preparation. Stand apart classes like human relations are not enough to address a problem of this magnitude. Teachers need to be helped by skilled facilitators not to be afraid of talking about these issues, or pretending they will go away if they don’t acknowledge them. Teachers need to learn ways to integrate social justice teaching with their curriculum, but also ways to initiate dialogue about these issues in their classes. When they begin to feel more comfortable with these issues, they can begin to realize the tremendous benefits of discussing literature or history, or even differential equations with a diverse group of students who bring vastly different histories and perspectives to the task. None of this will be effective if we don’t eliminate the tracking system as it currently exists. We need to look at ways to provide the supports students need to succeed without labeling them or making assumptions about their effort, motivation or future aspirations based on these classifications. The task is massive and overwhelming, but possible. I was energized by talking with Lisa Yates’s two classes of human relations students, even though some of the things they told me were difficult and painful. I was more impressed with the fact that they could talk about them, and that they could talk about them with me, a stranger, and that they could talk so honestly about them with each other. After viewing the video that her students had uploaded to YouTube for their final project, as both of us were wiping away tears, Lisa Yates remarked, “See what I get to come and do every day?” Later she thanked me for witnessing her students and called them “amazing human beings.” I want every teacher to feel that way about all of his or her classes, because I want that kind of teacher, who delights in all students at least some of the time, for all of our children. Works Cited "Attendance and Enrollment Reports." NH State Department of Education. NH State Department of Education, 2012. Web. 27 Feb. 2013. Becerra, David. "Perceptions of Educational Barriers Affecting the Academic Achievement of Latino K-12 Students." Children and Schools 34.3 (2012): 167-77. Print. Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. Racism without Racists: Color-blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003. Print. Brindley, Michael. "Proposal Would Delay Leveling for Nashua Sixth Graders." The Nashua Telegraph 21 Sept. 2011: n. pag. Print. Bucholtz, Mary, and Kira Hall. "Finding Identity: Theory and Data." Multilingua - Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication 27.1-2 (2008): 151-63. Print. Camayd-Freixas, Yoel, Gerald Karush, and Nelly Lejter. "Latinos in New Hampshire: Enclaves, Diasporas, and an Emerging Middle Class." Latinos in New England. By Andrés Torres. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2006. 1-17. Print. Conti, Katheleen. "Residents Drawn by Affordable Housing, Jobs." Latinos Migrate to Nashua NH. The Boston Globe, 9 Nov. 2003. Web. 08 Jan. 2013. Delgado-Gaitan, Concha. "Culture Literacy and Power in Family Community School Relationships." Theory Into Practice 51.4 (2012): 305-11. Print. Evans-Brown, Sam. "Trials for Latinos at Nashua High School." New Hampshire Public Radio. NHPR, 16 Nov. 2011. Web. 08 Jan. 2013. "Latino College Completion: New Hampshire." EdExcelencia.org. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 Jan. 2013. Lichter, Daniel T., and Kenneth M. Johnson. "Immigrant Gateways and Hispanic Migration to New Destinations." International Migration Review 43.3 (2009): 496-518. Print. "New Hampshire." USHLI Almanac. United States Hispanic Leadership Institute, 2012. Web. 08 Jan. 2013. Petersen, Meg J. Vivencias: Writing as a Way into a New Language and Culture,. Diss. University of New Hampshire, 1991. N.p.: Unpublished, n.d. Print. Tatum, Beverly Daniel. "Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?" and Other Conversations about Race. New York: Basic, 1997. Print. Trivilino, Peggy L. "Words Do Matter in Leveling Debate." The Nashua Telegraph 23 Sept. 2011:. Vasquez, Daniel W. "Latinos in New Hampshire." Site. Gaston Institute Publications, n.d. Web. 08 Jan. 2013.