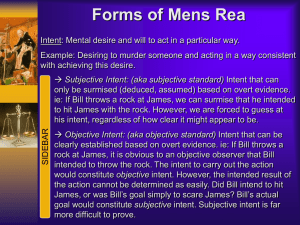

Criminal Law - NYU School of Law

advertisement