Loken, Lommerud and Lundberg - UCSB Economics

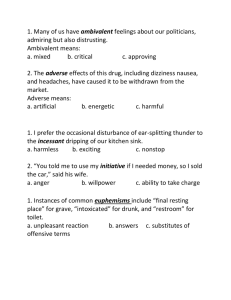

advertisement