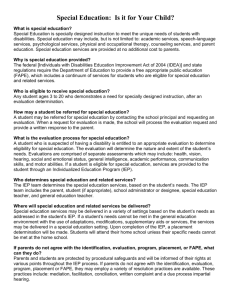

Handout #4 - Region 4 | Parent Technical Assistance

advertisement