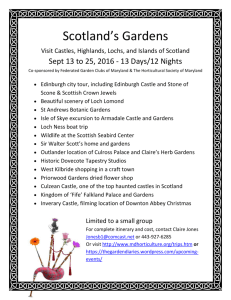

Discursive Representations of Young People in the Beetham Gardens

Discursive Representations of Young People in the Beetham

Gardens:

Marginalization, Discourses and Governmentality

A Research Paper presented by:

Aleisha Holder

Trinidad and Tobago in partial fulfillment of the requirements for obtaining the degree of

MASTERS OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES

Specialization:

Children and Youth Studies

(CYS)

Members of the Examining Committee:

Roy Huijsmans

Kristen Cheney

The Hague, The Netherlands

December 2012

1

2

List of Acronyms

CAO Community Action Officer

CAC Community Action Council

ILO

ISS

LAC

MLI

CSO

CSP

CYS

IDB

PBR

P-O-S

Central Statistical Office

Citizen Security Programme

Community and Youth Specialist

Inter American Development Bank

International Labour Organization

Institute of Social Studies

Latin America and the Caribbean

Making Life Important

Priority Bus Route

Port-Of-Spain

3

Abstract

“At risk” youth has become a buzzword within the international arena for several years.

However, this term has only gained momentum within Trinidad and Tobago since 2008 upon the introduction of the Citizen Security Programme (CSP); a programme partially funded by the

Inter American Development Bank. This programme specifically targets those living in “high needs” communities such as “at risk” youth.

In this paper I argue that that this label, when deconstructed presents an image of young males who are prone to violence, crime and delinquency. This image becomes highly problematic when these young men live in an already marginalized community. The intersection of marginalization because of location together with age and gender can have potential harmful effects such as resulting in increased surveillance of this group.

Relevance to Development Studies

Within the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region and more notably in the Caribbean, development policies and interventions targeting young people are using the terminology of risk. This discourse of youth “at risk” is seldom problematized and continues to be applied to young people and more particularly, to young men, throughout the region. The views of the young people themselves in relation to discourses such as these are also underrepresented.

Thus, I hope to contribute to the global literature on this topic highlighting the experience emerging from the Trinidad and Tobago context. With no attempt to make generalizations for the Caribbean experience, it is hoped nonetheless, that this research will spark further investigation into the dominant youth discourses and constructions within the Caribbean region.

4

Keywords

Discourse; “at risk” youth; marginalization; spatial segregation; citizen security; Inter American

Development Bank; Beetham Gardens; governmentality; Latin America; Caribbean; Citizen

Security Programme.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my family: Irene, Ayanna, Allyson, Andy and Lincoln for their incredible support throughout this process. You have been patient with my late nights, have read numerous drafts of this research paper, taken photographs and kept me sane for the past few months. Thank you for your prayers and love and for taking this journey with me.

I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor who has tirelessly championed my cause, and who determinedly caused me to question every bit of data, my reasoning and thought processes (even until the last moment!). His dedication to ensuring that I was fair and balanced all helped me greatly in getting to this final product. You have been a great help and great guide and ensured that I always did my best.

To my friends in the Hague; Vera, Preeti, Catalina, Thandi and Sandra, my soul sisters, thank you for your undeniable support, for the lovely RP chats, for your useful comments, the pressure groups and for always being great cheerleaders.

A big thank you to all of my research participants without whom this research paper would not have been possible. Thank you for being honest and open and allowing me into your community, workspace and lives. I hope that this research paper will shed some light on the current situation as I understand it.

5

Contents

Relevance to Development Studies

Chapter 1: Locating the research: The Beetham Gardens

The Beetham Gardens: A Marginalized Community.

Chapter 2: Methodology: Researching ‘At Risk Youth’

Positionality: My Role as Researcher

Chapter 3: Discursive Representations of young men in the Beetham Gardens.

Chapter 4: Effects of the “at risk” discourse.

Young People’s relative powerlessness.

List of Figures

Figure 1.0- Research Question and Sub Questions ..................................................................................... 21

List of Photographs

Photograph 1.0 sign depicting Beetham Gardens view from Highway…………………………………………………..10

Photograph 2.0 protest aftermath on PBR in 2006…………………………………………………………………………….....14

Photograph 3.0 showing the view of the wall from the highway…………………………………………………………...16

6

Photograph 4.0 depicting the length of the wall……………………………………………………………………………………17

Photograph 5.0 depicting the length of the wall……………………………………………………………………………………17

List of Tables

Table 1.0 indicating participants for qualitative interview……………………………………………………………..........24

7

Introduction

In this paper I critically interrogate the ‘at risk’ discourse underpinning many development interventions concerning youth. The focus is on Trinidad and Tobago, and more specifically on youth from the Beetham Gardens, an area which can be said to be marginalized due to the intersection of a series of geographical, historical, economic and socio-political relations.

In this paper, I show how the label of “at risk”, groups together young men from this community as particularly prone to crime and delinquency; it identifies deficits within the young men’s character which makes them so proned and which results in the legitimate introduction of preventative policy interventions. As Kelly (2001:24) argues “discourses of youth at risk are framed by the idea that youth should be a transition from normal childhood to normal adulthood”. These interventions are meant to allow these young men to change themselves and their situations, make better choices and to follow the path to normativity once again.

The difficulty of this however is that it totally obscures the fact that these young men come from a context where they already experience processes of marginalization because of where they come from. Furthermore, it conceals wider macro-structural processes which may be affecting these young men’s position in society.

The Beetham Gardens is distinguished from the rest of Trinidad due to its history of labeling, stereotyping and neglect from the state and represents an “other” within the society. Therefore implementing more programmes for “at risk” youth without failing to address these already existing issues will be counter-productive and will only have negative effects on these young men from this community.

This paper doesn’t attempt to dismiss the fact that some young men do participate in criminal activities but rather seeks to problematize the “at risk” discourse, the policy which enforces it and its implications for young men who originate from a context where they may already face challenges.

8

I therefore ask and hopefully answer How do discourses of risk, particularly the label of “at risk” impact upon the lives of young men from a marginalized community, the Beetham

Gardens?

To answer this question I explore the history and emergence of the Beetham Gardens as a community; the constructions of youth both locally and globally, the discursive underpinnings of the “at risk” rhetoric and most importantly how young people in the Beetham Gardens perceive themselves and how they think the wider society perceives them.

Chapter 1 of this paper locates my research within the context of Trinidad and Tobago and more specifically, the Beetham Gardens. This investigation of context reveals the stimulus for doing research within this community and for my research questions. Chapter 2 presents a detailed exploration of my methodology and the ethical challenges faced during research.

In chapters 3 and 4, I focus on the potential pitfalls of this discourse of risk and label of “at risk”.

I begin by deconstructing the label and then turn my attention to how this label results in homogeneity, individualization of risk and increased surveillance of young men. I present a different view of the “at risk” label and how it may not be viewed as dangerous depending on who is looking. I take the discussion further to include the experiences of the young men which are usually lost as a result of the label of “at risk” and I explore notions of power.

In the Caribbean literature on issues surrounding young people there is an underrepresentation of the views of the young people to whom this label is affixed. Therefore a common thread in all of my chapters is the presentation of the views of the young men who live in this community; views which are presented in the local vernacular of the country as I didn’t want to interfere with my participants’ expressions and I wanted to present their views in as an authentic manner as possible.

In my concluding section, I summarize the main evidential points and arguments as explored in chapters 1-4. Here – I link the processes of marginalization of the Beetham Gardens as a place and how the “at risk” label affects young men from that community.

9

In studying the Beetham Gardens, my research focuses on a deprived and marginalized community with its own history and social problems. However, I believe that the issues explored in the lived experiences of young men in this community may be relevant to the study of other young men from marginalized communities whether it be within the East Port-Of-Spain regions or at a global level.

10

Chapter 1: Locating the research: The Beetham Gardens

Photo 1.0 of the Beetham Gardens (view from the Highway)

1

This chapter identifies the several processes which contribute to the marginalization of the

Beetham Gardens as a community. I do this by briefly highlighting the wider context of Trinidad and Tobago and then identifying the specific history of the Beetham Gardens. In photograph 1.0 the welcome sign identifying the community can be seen from the highway which is placed on the wall running along the community (a process of spatial segregation which will be explored later on in this chapter).

1 Photograph courtesy Lincoln Holder for the purposes of this research.

11

Trinidad and Tobago is a twin Island Republic and is the southernmost Caribbean island, nestled close to Venezuela. The two islands, Trinidad and Tobago became incorporated into a single colony in 1888, however despite being a twin island Republic the focus of my research will be on a specific community within Trinidad and not Tobago. This is for practical reasons, being that although Trinidad and Tobago are one country, discourses of crime and violence vary between them, with more emphasis usually being placed on Trinidad and not Tobago. Further to this

Trinidad is my home and the context of Beetham Gardens is more familiar to me.

The country has a long history of slavery, indentureship, social inequalities based on race, class and colonialism, only achieving its independence from Britain in 1962, some 50 years ago. In

2010 2 the population of Trinidad and Tobago stood at 1,317,714 people, with 261,438 persons between the ages of 15-24 (Central Statistical Office, CSO) and the dominant ethnicities being

Afro-Trinidadian (persons of African descent) and Indo-Trinidadian (persons of Indian descent).

The Beetham Gardens: A Marginalized Community.

“Life on the margins is made it is not natural

(Wyn and White 1997:123)

Marginalization can be defined as processes by which access to means of production is limited or impeded; there is limited or diminished access to decision making, distributional processes and policies, services and benefits due to position in the social structure (my emphasis) and marginalized persons are either excluded from participating in the productive process or their contribution is appropriated (Kuitenbrouwer, 1973:9). Wyn and White take this definition further by indicating that marginalization refers to aspects of life experiences through which inequality is structured (Wyn & White, 1997:121). Wyn and White (1997:121) also make

2 This is the most up to date data from the Central Statistical Office and is based on the 2000 Census.

12

reference to the characteristics of those who are marginalized as including, residing in the poorest housing estates, having limited or meager income, persons being compelled by market forces to sell their labour but are restricted from doing so, due to structural inequalities.

The notions that inclusion or exclusion from full participation within society depends on position within the social structure and that inequalities can be institutionalized within social structures are relevant for our purposes here.

The Beetham Gardens can be considered as existing in the lower echelons of Trinidadian 3 society. This low status has been due to several systematic processes and characteristics which are explored herein and which contribute to their diminished access to services and to the decision making sphere. Further to this, the marginalization of Beetham Gardens has resulted in impediments to fully entering the labour market.

The Beetham Gardens is located in South East Port-Of-Spain (P-O-S), Trinidad, immediately outside of the administrative centre of the city. It is bounded by two major roadways which lead into the capital city; the Beetham Highway (“the Highway”) runs alongside the community and is one of the main points of entry for motorists from East and Central Trinidad into

Northern Trinidad. On the other side of the community is the Priority Bus Route (PBR) which is the main roadway for public transportation into the city. Since thousands of commuters use these roadways to enter into P-O-S on a daily basis, the community of the Beetham Gardens is highly visible to wider society – yet it remains highly marginalized.

Previously known as Beetham Estate and now called the Beetham Gardens, this community was born in the 1970’s as a resettlement community for those who lost their homes in other surrounding areas of the city due to a fire, as well as for those who lived in informal settlements on the outskirts of the capital city (Cambridge, 2003:6). The community was a project of the government to regularize housing at that time and is a relatively ‘young’ one in terms of its existence and is still comprised of persons who initially moved into the housing settlement in the 1970’s.

3 Trinidadian is the term for a person who comes from Trinidad.

13

According to the CSP the area is also considered as comprising of low to middle income families

(CSP website, 2009) thus having lower economic status within the society. This is compounded by the fact that this area has been identified by the CSP as a site for violence and criminal activity. There are certain characteristics of the Beetham Gardens which contribute to its low status and low social position within Trinidad and these are explored below.

The Environment

The Beetham Gardens is plagued with environmental problems since it is situated between an industrial site (on which an alcohol distillery is located) and one of the national landfill sites which fails to dispose of the waste in a sanitary way. Waste is disposed of improperly and results in a foul smell engulfing the entire area, including the highway and the community.

Consequently, the stench, which can be smelled by commuters, is usually attributed to

‘Beetham people’ by the wider public.

Political Action

The community is frequently featured in newspaper and television news stories, and due to its visibility by the wider public it is discussed quite often. The Beetham Gardens is also well known for its political action, which usually manifests in protesting and blocking of the highway with debris. Two protests have already taken place this year on May 24 th 2012 and June 28 th 2012 4 .

Protesting in this manner, has the effect of disrupting the traffic flow into the capital city. A usual scene of the aftermath of protests is depicted in Photograph 2.0 below which was taken at a protest in 2006.

4 Further information about the protests can be found on these links http://www.trinidadexpress.com/news/_Beetham_residents_stage_protest_over_police_raid-124752329.html

and http://www.trinidadexpress.com/news/Beetham_residents_block_highway_in_fiery_protest-153888065.html

.

14

Photograph 2.0- Protest Aftermath on the PBR in 2006

Photo courtesy of The Trinidad Guardian 5 .

The main requests during the protests were for employment for young people; to denounce purported police brutality and oppression as well as indicating dissatisfaction with the state’s treatment of the community. Two of my young participants confirmed taking part in the most recent protest and when asked about this protest action, Rex, a 19 year old male from the community said the following:

“dem (them) fellas block road and […] we get work normal …. When the people fighting for their rights when they block that road nobody can’t pass… they come and ask what allyuh (all of you) want… we does get they attention and get work

… one time, opportunity one time.”

(Quote from Interview 1 on 27/08/2012with Rex 6 )

What Rex is stating here is that one of the ways residents gain improved access to benefits of employment policies is by protesting and blocking the roadways with debris. In this way their demands are almost immediately met by those in the decision making sphere. This can be interpreted as the resident’s inability to access those in power in other more normative ways and this as Kuitenbrouwer (1973:9) has indicated is a feature of marginalization.

5 Link to the online story and photograph can be found here http://legacy.guardian.co.tt/archives/2006-08-11/news6.html.

. I could not locate photographs of the most recent protests.

6 Pseudonyms are used for my young participants.

15

Spatial Segregation

In Trinidad, like in most other countries, where a person lives is one marker of affluence and status within society. The colonial past means that spatial segregation has therefore been part of its history, based on race and colour and more recently on income and class (Mycoo,

2005:135). Numerous oil booms and failure to redistribute wealth in Trinidad during the 1960’s led to increased inequality and resulted in Black Power Riots in the 1970’s. After the riots, the government responded by subsidizing and regularizing housing and other social services

(Mycoo, 2005:136-137). In a study on gated communities within Trinidad, Mycoo notes that the ones that reside in gated communities in the West of Port-of Spain represent the more affluent and upper-middle classes of Trinidad (2005: 138).

The “West” in Trinidad, which is actually the Western part of P-O-S is the pinnacle of wealth and status and usually connotes images of socio-economic status and affluence. On the contrary, the East of P-O-S, where the Beetham Gardens is located, conjures images diametrically opposed to those of the “West”. East P-O-S evokes images of lower socioeconomic status, poverty and high levels of crime.

Location therefore becomes an important difference in the Trinidadian context. When asked about the obstacles and barriers that young people in the Beetham Gardens face, Abinta Clarke the Community Action Officer (CAO) with the CSP for the area indicated that their geographic location was one such barrier, just the idea that they [are] in the East Port of Spain area which comprises of

Laventille and which has had a stigma from 1970 all the way back …they live next to a dump. If I live in a community where the environment doesn’t seem friendly at all…. if I have to wake up every morning and there’s a stench...I grow up in that, my children grow up in that, my great grandchildren grow up in that, it says something , it makes them feel like they [are] not moving

(Quote from Interview with Abinta, 29/08/2012)

16

Location therefore becomes a difference which can be identified by those from other communities within Trinidad and even those within the Beetham Gardens. All but one of my young participants indicated a strong desire to leave the Beetham Gardens when they could afford to do so. Joseph, a 21 year old male indicated that once you attained a certain level in life, you have to “get out” 7 . The Beetham Gardens was a place to leave so that he could seek better opportunities and a better life somewhere.

But, further to location being an issue, there has been actual spatial stratification of this community. In 2008, a wall, dubbed as the “wall of shame” (Hassannali, 2008) was constructed by the National Government along the entire community on the side which is bounded by the

Highway (see photographs 4.0 and 5.0 which gives an idea of the length of the wall). Although the wall does not obscure the entire community, trees were planted on mounds in front of the wall which have the effect of obscuring certain parts of the community from the view of those who pass along the highway. Photograph 3.0 shows the view of the wall from the Highway.

Photograph 3.0 showing the view of the wall

and the trees planted on mounds in front of the wall from the highway 8 .

7 Notes taken from interview on 27/08/2012

8 Photos courtesy Lincoln Holder for the purposes of this research.

17

Photograph 4.0 depicting the length of the wall.

Photograph 5.0 depicting the length of the wall.

Photographs 4.0 and 5.0 gave an indication of the length of this wall which runs along the community and the visibility of this community due to its proximity to the highway which could be seen in photographs 3.0 and 5.0.

The wall’s construction began around 2008 and coincided with the Summit of the Americas and the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting which was hosted by the Trinidad and

Tobago government in 2009 and was termed as a beautification drive by government officials.

18

A more obvious interpretation would be that it was perhaps an attempt to hide the galvanized 9 houses which did not represent Trinidad as the economically thriving city it purports to be. This wall led to outrage on a local and international level but still remains.

This wall can be deemed as blatant spatial segregation of the community from the wider society and a clear example of the ‘horrific treatment’ referred to by Link and Phelan

(2001:370) which is legitimized when there exists labeling, stereotyping and differentiation between groups of “them” and “us”. The Beetham Gardens is the ‘other’ in this context of

Trinidadian society.

How urban space is organized is reflective of how different social groups relate to each other; their differentiation and separation (Caldeira 1996:55). Although Caldeira speaks primarily of the fortified enclaves of the rich in Sao Paolo, the underlying rationale is still applicable to the

Beetham Gardens.

The wall is a reflection of the type of interaction between the different factions of society and is a result of the processes of systematic marginalization of the people who live there. According to Mac Donald and Marsh (2005:166) who discuss the ways that inequalities are structured through the local housing market in a UK neighbourhood, these spatial processes serve to

‘widen and harden local social divisions between the included and excluded’. Processes such as that and the actual building of a wall can be viewed as ways through which inequality become clearly visible at the ground level.

Although aware of the implications of the wall, a tension is revealed when the participants were asked about how they view it. One participant, Rex, explains they trying to hide what them (the government) make ...they trying to hide the ghetto community which them have so ….it was them job in the first place to see about it not because of summit or somebody coming they want to make sure it look nice…that is not right

9 Galvanize is a type of material usually used for roofing of homes and can be seen in photographs 3.1 and 3.2.

19

(Quote from Interview 1 on 27/08/2012 with Rex, 19, male)

His neighbour and an interview participant, Joseph (21, male) added however that the wall meant nothing; that those who were upset about the construction of the wall were then hired to complete its construction and so were happy that they were employed 10 .

This tension between satisfying one’s economic needs while further contributing to the active spatial marginalization of your own community reveals some of the complexities of this community. The need for employment and for economic independence resulted in residents effectively reinforcing the marginalization of their own community.

As outlined above, the conclusion can be drawn that the Beetham Gardens as a community is marginalized. The community has a low status within the wider context of Trinidad and Tobago which is contributed to by its environment and its location. There are indications of limited access to services and to decision making on issues which affect young people such as’ youth unemployment’.

Certain processes such as the building of the wall reproduce the marginalization of this community. This reproduction of processes of marginality, are known to my participants and although in some instances they tend to reinforce it (by building the wall) they also try to resist it (political action). However next to such spectacular forms of agency, the marginalization of the Beetham Gardens is reproduced and experienced through a range of everyday experiences which is explored in the following chapters in much more detail.

In the chapter 3, I show how marginalization of the community is reproduced and the marginalization of young men is produced through the CSP and its label of “at risk”. Young men are specifically targeted and attention is drawn to them as “at risk” youth, linking them all to crime and delinquency.

10 Notes from interview with Joseph, 27/08/2012.

20

It is in this context that my research question arises:

How do discourses of risk, particularly the label of “at risk” impact upon the lives of young men from a

marginalized community, the Beetham Gardens?

I ask: who is an “at risk youth”? What does this label imply and why does it matter? How does this label affect young men from this community? What is excluded when we frame young people as “at risk”?

However, before I fully explore the implications of the

CSP and the rhetoric of risk, in chapter 2 I identify the methodology used to answer the research question and sub questions as seen in Figure 1.0.

Research Question: How do discourses of risk, particularly the label of “at risk” impact upon the lives of young men from a marginalized community, the

Beetham Gardens?

Sub questions:

Who is an “at risk” youth ?

What does this label imply? Why does it matter?

How does this label affect young men from this community?

What is excluded when we frame

young men as “at risk” ?

Figure 1.0- Research Question and Sub Questions

21

Chapter 2: Methodology: Researching ‘At Risk Youth’

My two main methodological approaches for this research are ethnography and discourse analysis. As indicated by Huijsmans (2010:53) ethnography can go beyond participant observation and can in fact be used as an overarching guiding framework. I approached my research in this way and used several methods such as qualitative interviewing, focus groups and participant observation to complement each other to gain some insight into the everyday lives of my intended respondents.

This technique of mixing methods is known as “within methods” triangulation whereby several techniques within a specific method, in this case, the qualitative method, are used ‘to collect and to interpret data’ (Jick 1979:602-603). Triangulation can be an essential tool in providing the reader with a thick description of the phenomenon (Jick 1979: 608-609) being studied.

My research was rounded off by analysing the discourses of risk, the label of “at risk” and other labels affixed to young men of this community. I also examined the interactions between discursive representations, social practices and power which is what Yates (2004: 233) describes as discourse analysis. To do this I examined:

government speeches;

Inter American Development Bank (IDB) policy documents;

official documents of other international agencies;

newspaper articles and

personal interviews with the CSP staff and the young men.

This last aspect of my discourse analysis was especially important since the CSP staff members are the ones putting the discourse into practice and the young men are the recipients of it. This discourse analysis shed light on my sub questions: who is an “at risk” youth and what does this label (of “at risk”) imply.

22

My approach to ‘youth’ in this paper, falls in line with social constructivism whereby ‘youth’ is viewed as a social construct reflecting the existing ‘sociopolitical’ environment of the society in which young people live (Comaroff & Comaroff 2005:19). Therefore the terms ‘youth’ and “at risk” as it refers to young men must be deconstructed to reveal underlying assumptions and perceptions about young men from the Beetham Gardens which the wider society holds.

Methods: Data Collection

Semi-Structured Interviews

My fieldwork was undertaken between the months of August and October 2012. I conducted a series of semi-structured interviews with six young men from the community between the ages of 14 and 21 years. I chose to interview participants within the age range as provided by the

CSP (7-24) as this demographic cohort defined by them forms part of how ‘youth’ are constructed by this policy.

Semi-structured interviews were chosen as the preferred method to permit my “exploration […] of the subjective understandings of the social world” (Yates 2004: 158) of these young men.

These interviews allowed me to gain insight into the young men’s lived experiences, their perceptions about the CSP and their beliefs about how society viewed them. These interviews explored themes of labeling, discrimination and were especially helpful in answering my sub questions: what is excluded when we frame young people as “at risk”? and how does this

label (of at risk) affect young men from this community.

The interviews with the other 5 participants could be referred to as ‘stakeholder interviews’

(Mac Donald and Marsh, 2005:41) and which comprised of the members of the CSP and members of the Community Action Council (CAC), the community body responsible for implementation of numerous programmes. The stakeholder interviews assisted in answering one of my sub-questions :who is an “at risk” youth?

The interviews usually lasted between 1-2 hours and most were tape recorded. The interviews were then listened to and although the entire interview was not transcribed verbatim, essential

23

elements and key discussions were. However, this meant that sometimes interviews had to be listened to repeatedly when new themes which were not initially identified, subsequently arose resulting sometimes in an ineffective use of time. These interviews occurred in various locations including but not limited to, the participants’ homes, at a community school and on the street corner amongst other places. I preferred as much as possible to go to my participants, wherever they were, including their community since this site formed an important part of my research.

The table below itemizes who my participants were, the number of interviews held, the dates of the interviews and interview type.

Table 1.0 indicating participants for qualitative Interviews.

Research participant

Date of interview No. of formal interviews

Abinta Clarke – CAO 29/08/2012

Ryssa Brathwaite-

Tobias- Community

29/08/2012

1

1

Interview Type

One-on-One

One-on-One and youth specialist

Rick* 13/09/2012 1 One-on-One

Randy*

Juliet

Kane*

Joseph *

Rhino*

Rex*

27/08/2012

28/08/2012

14/09/2012

29/09/2012

22/08/2012

28/08/2012

27/08/2012

28/08/2012

14/09/2012

29/09/2012

27/08/2012

28/08/2012

4

1

3

1

1

2

One-on-One; Joint

One-on-One

Joint

Joint

One-on-One;Joint;One-on-One

Joint

24

Jerome*

Shawn*

28/08/2012

14/09/2012

Shawn* , Kane* , 14/09/2012

Rhino* , Daniel*,

Anthony*

1

1

1

Joint

One-on-One

Informal focus group

*Pseudonyms used

An expanded version of this table can be found in Appendix 1

Some interviews were joint as this appeared to be more feasible time wise. Due to the unstructured attempt at sampling and time constraints, I had to maximize any window of opportunity that was available to me. On three occasions, I began one-on-one interviews which subsequently became joint interviews because the participants were available at that time.

In all cases where joint interviews were held, the participants knew each other, some of whom were neighbours whilst the others participated in the last CSP event together, Shoot to Live. As a result, the interviews flowed well, in some cases with the participants adding to each other’s statements, contesting and agreeing. This technique proved well in exposing a myriad of experiences regarding a specific incident or issue despite my small sampling size. Where there were contradictions or variations of experiences, these were noted and used to highlight the nuances that exist in the everyday realities of these young people.

My key themes, pre-interview, were broadly the “at risk” discourse and processes of marginalization. However my interviews revealed that the theme of labeling as related to the

‘at risk’ discourse and the ways in which it interacted with marginalization also needed attention. Indications of coping with economic pressures of capitalism and my participants’ resilience emerged as new themes and proved useful in my discussions in this paper. The

‘relative openness’ (Mac Donald and Marsh, 2005:43), of qualitative methods encouraged this broadening of my key themes.

25

Focus Groups

In Table 1.0, I also refer to an informal focus group which can be defined as an unplanned focus group meeting in an informal setting with little structure (Morgan, 1996:130), which was the case in my present research. These informal discussions arose at the CSP launch of the photography component of the Shoot to Live intervention and followed the initial set of qualitative interviews. It must be noted however that two new participants Daniel, a 16 year old male and Anthony, a 17 year old male were newly introduced to me at this event but they did form part of this discussion. Furthermore, Joseph who was one of my previous interviewees was absent during the informal focus group. I found that since some of the young men already recognized me from a prior interaction, the discussions flowed well, as there was already a small element of trust due in part to their recognition of me.

I was also able to use some of the information gathered in the initial interviews as starting points for discussion with the wider group and to check some conclusions from a wider pool of persons in a short time (Morgan, 1996:134). I hardly played the role of moderator in this discussion as the role of observer was far more interesting and I did not want to disrupt the organic flow of the conversation which can be a potential pitfall of moderating (Morgan

1996:145). In this way I was able to insert myself into the conversation quite easily. I engaged in conversation with the young men in other topics which they discussed for themselves, which included playful ‘teasing’ of other members of the group (some of this material forms part of analysis in my research); sometimes answering questions directed to me; as well as playing on a playground in a park nearby without much talking.

Participant Observation

Participant observation occurred mostly during my observational walk around the neighbourhood with my guide, which also served the purpose of having people in the neighbourhood see me with a resident; why this was important is discussed in the section regarding my positionality). I also talked informally with some of the young people and the other participants in the sample. Also during my final interview session I spoke with one of the young men on a street corner for about 45 minutes. This session was not recorded as I felt this

26

locale was too sensitive for me to openly and visibly record my participant. As a result I listened and after the interview I made notes. These informal talks proved to be quite valuable for my data collection because the participant and I had by now built some rapport.

Ethical Considerations

My participants were given pseudonyms so as to protect their identity. Although anonymity was not necessarily requested by them, I thought it would be best, in light of the fact that early on in my research, the CSP personnel requested that I submit a draft of my research paper before its submission. Since I was aware that there was a possibility of the CSP staff reading my research paper it would be likely that my participants could be identified and I was unsure how this would affect interpersonal relationships between the participants and the organization.

Thus out of an abundance of caution I decided to anonymise some of my participants, especially the young people who may in the future want to participate in CSP events. The other participants who were not anonymised were the CSP staff I interviewed as well as Juliet Davy who indicated that her identity could be maintained.

Early on in my research process, the CSP staff indicated their hope that I would forward to them a draft of my research paper for their review before it was considered final. After the initial mention of this by way of email, this issue was never brought up again. In light of the fact that my drafts kept changing quite substantively until the day before submission, I was unable to acquiesce to this request fully. A copy was however forwarded a few hours prior to submission to the CSP office. This caused to me deal with internal questions as to what extent was I obligated to acquiesce to this request and what control the CSP could have over my analysis.

Although the response to my paper could have formed part of my analysis for my paper, there was insufficient time to deal with it. These questions are therefore left for me to ponder on.

My sample was chosen based on availability and willingness of the participants and the majority was facilitated through my attendance at various CSP events. Most of the young men from my semi structured interviews were older than 18 and so parental consent was not required. Two of them were under 18 and for one, parental consent was sought as his mother was a CAC member to whom I explained my research and she volunteered her son. The other young man

27

was interviewed at a CSP event to which none of his parents attended. As a result an informal interview was conducted but consent was not officially sought from a guardian. For my interviews with the CSP staff, they were asked to sign consent forms, as it was my feeling that a formal document would assist in giving me legitimacy. The forms can be found in Appendix 2 along with other documents submitted to the CSP.

I chose to focus more on the accounts of the young people and the official CSP personnel, due partially to constraints of space and the desire to highlight the nexus and tensions between what a policy intends to do and what it actually does. As a result some of the formal and informal interviews with the Community Action Council (CAC) members were not directly included in this research paper.

Managing My Data

The information gathered was then compared and contrasted to statements from my secondary sources which were the subject of my discourse analysis. In some cases where linkages were made or tensions were revealed, prior to an interview, these issues would be highlighted and brought up for clarification, if not I tried my best to present them here, if they could not be reconciled. As indicated earlier certain choices to include and exclude data were made based on relevance to my selected themes.

Positionality: My Role as Researcher

As Ng (2011:439) suggests, we should not shy away our subjectivities even though they may raise tough questions and dilemmas but which can result in ethically fulfilling ethnographic research.

Methodological biases

Crossa (2012, 110:132) in her article argues that one’s subjectivities and positionality affect methodological and theoretical choices which may frame interaction in the field and the

28

research questions. She suggests that theoretical approaches form part of the research process and can sometimes reveal a researcher’s biases. In my case, I approached my research from a social constructivist perspective as discussed above with a focus on structures of power and inequality. For the most part, I viewed power as something enforced by the state and international organizations on persons who were marginalized. Initially I believed that, power was operationalized as flowing from top to bottom, however my research in the field revealed that power can be exercised by all the different players including those viewed as marginalized.

This issue is explored later in my paper in my discussions on power and agency.

My propensity to lean on this theoretical framework could be as a result of the way I view my own history. As a single black female who also originated from an area which was not affluent and which community experienced several social issues such as domestic violence, drug problems and neglect from the state, even before I entered the field I felt connected and empathetic with my research community.

I sought to balance this potential bias to view my participants as victims of structural inequality by being reflexive about the way I presented myself, my line of questioning and the way I phrased my questions. For example, in the first set of interviews I held, I used the word stigma quite often and my participants would use this term when responding to me. In my case stigma has a very specific meaning and falls in line with my focus on power relations and inequality. I soon realized that I needed to be careful of my use of the term for fear of my participants using this word although they wouldn’t have ordinarily used it or if they wished to convey some other idea. As a result I became aware of my usage of this term, attempting to use it less or not at all.

Age

A researcher must also acknowledge that certain positions and identities do bring with them different levels of power and consequences (Ng 2011:446). Thus whether I was empathetic or not, I entered the field as a researcher which brings its own connotation of power within the research site. Interestingly I found that my age proved to be an equalizing force and which assisted in building rapport between myself and my young participants in much the same way that Ng (2011:448) found her education level assisted in neutralizing her gender in a site where

29

elder men were at the helm. After asking my age the young males even invited me to spend time with them playing on the playground and I was allowed to be an active participant in their world. I believe this contributed to building rapport with my participants.

Although their ages varied and I was older than they were, I was close enough to their ages of

14-21 years, to be able to communicate with them, some also commented on the fact that I looked younger than my age and thought I was their age. The ease of these interactions was not necessarily felt with some of my older respondents who also could not believe that I was actually twenty six years old. Upon reflection I should have prodded my respondents further to enquire why knowing my age was relevant to our discussions.

Gender

My experience in the field demonstrated that at times my gender worked both to my advantage and proved to be a minor distraction when conducting my research. The fact that I was female did mean that, in dealing with young males between the ages of 14-21, several advances were made to me with regards to entering into relationships with some of them. This was not a major drawback since it was never brought up in any serious manner but was the subject of what I deemed to be playful banter between the boys about my presence in the area.

Prior to entering the field however, informal discussions with residents of the area and persons in general all seemed to indicate that being female would mitigate the fact that I was unknown to the residents within the area. I was also advised that entering the community with someone from the area would further reduce the potential for residents to view me with suspicion. This advice was heeded and I entered the field with a resident and member of the CAC.

The presence of a guide would serve to alter my positionality from being viewed as an outsider who would not be welcomed to one who was. This intentional move to alter my position was necessary to gain access to my first five participants who felt comfortable with my guide Randy, who asked them to participate in my research.

30

In her paper, Notermans (2008: 364) indicates that sometimes it is necessary to intentionally alter your position by aligning yourself with an individual from the community with whom the participants could feel comfortable. Notermans (2008:364) writes about positionality with regards to her research about fostering young children and her decision to use a well-respected foster mother of the area with whom the children felt comfortable. This technique helped her to produce results, where otherwise she would not have gotten any data from her research with the young children (Notermans, 2008: 364).

Although the accompaniment of my aide was highly valuable to my research there was an instance during the research process where one of my participants hesitated when asked direct questions about the CSP. I attempted to reduce any discomfort by asking my participant whether he was uncomfortable with my guide’s presence, if he wanted him to leave and in one instance my guide contributed to the conversation to put the participant at ease. This risk of data collection being negatively affected by aides and one’s position can be a real threat to research. Huijsmans (2012:339) in his research indicated that his position as a foreign researcher, a status usually affiliated with an international organization or the government resulted in his data ‘being littered with appropriate responses, evasions and miss- presentations’ to promote certain requests or agendas by the respondents themselves.

Sometimes my participants appeared to evade answering direct questions, hesitating before responding to direct questions about the CSP and gave what appeared to be appropriate responses. This was especially true for one respondent in particular who was interviewed in

Randy’s presence and in the informal focus group at the launch of the CSP Shoot to Live photography component. I felt a bit uncomfortable to ask them direct questions about the CSP as the CSP representatives were in attendance. In terms of my interviews with the CSP staff some responses did appear to betray a sense of political correctness, as one of my interviewees made a comment in one instance “ I don’t want to use a word that’s not suitable” in describing some of the issues she believed that young people from the Beetham Gardens were facing 11 .

11 Notes taken from interview with Ryssa Brathwaite Tobias , 29/08/2012

31

Outsider

My position as an outsider researcher became an issue when I travelled to the community for the third time. On my third visit I was going to attend a CSP meeting at a school in the area, but

I was unable to contact my guide prior to the meeting.

As a result I panicked at the thought of entering the community without a resident at my side.

This meeting was set to take place in the evening which meant that I would most likely be there late into the night, much unlike my other interview sessions which took place during broad daylight. This element of the time of entry into the community was verbalized by a friend who I met on my way to the meeting and who expressed concern over the fact that I was going into the Beetham at such a late hour reminding me that it would soon become dark. This served to heighten my sense of fear and anxiety and was almost enough for me to abandon my research.

Despite having gone into the community two times before, I was still quite afraid, bringing to my attention my still very deep–rooted conceptions about the area being unsafe and rife with violence and the fact that I was a female entering the community alone (a subjectivity which was initially seen as positive). Had I not made contact with my guide eventually, there was a real possibility that I would not have attended the meeting that day. This situation shed some light on my own personal experience of the effects of stigma on the wider society’s perception of security and crime in the area. I realized I also had contradictory feelings about this community; from a distance I empathized but when it was time for me to enter the field on my own, it was revealed that I too accepted on some level that this area was a bad neighbourhood.

This seemed similar to what Narayan (1997: 678) described as an ‘inverse process’ whereby our pre-existing experience absorbs ‘analytic categories that rename and reframe what is already known’ when a researcher studies his own society. I would add that this inverse process also includes not only putting names to our experience but causes the researcher to be reflexive when reframing such experience. Reflexivity has been described as an ‘internal dialogue’ (Ng

32

2011:441) which serves to raise one’s consciousness (2011:443) and is essential to creating thick descriptions about one’s research.

It is important to note that my time in the field revealed numerous subjectivities which assisted me during my research namely my age and my gender. I learned that sometimes it is necessary to alter your positionality as well, which in my case was done by entering the field with a guide.

However, before I entered the field, my own experiences affected my choice of theories and my approaches to my research shedding some light on inherent biases. In situations such as these it is necessary to be reflexive and constantly challenge my own perceptions and approaches to my research participants and to the data.

My methods assisted me in answering my research question and sub questions and my primary source of data collection was semi structured interviews. This however was complemented by participant observation, focus groups and discourse analysis of text and of interviews.

In the following chapter I delve into my analysis on the constructions of ‘youth’ and the “at risk label as it is proposed under the CSP.

33

Chapter 3: Discursive Representations of young men in the Beetham

Gardens.

The Beetham Gardens has a history of pejorative discursive representations of young people. In this chapter, I explore these labels by first examining ‘youth’ as a social construct within global literature. Then I turn my attention to labeling at a micro level with a focus on the “at risk” label. I argue that these labels are intimately related to the discourses of risk and serve to further entrench the already existing marginalization of the Beetham Gardens and the young men who live there.

Youth as a social construct

As already explained in chapter 2, I approach the question of ‘youth’ as a social construction reflecting the social context in which it is developed. ‘Youth’ are perceived in various ways oftentimes representing a duality even within the same country. Jones (2009:2) shows that

‘youth’ have been seen as persons to be celebrated and deplored; heroes and villains and such duality results in ‘youth’ having an intrinsic bipolarity according to Comaroff &Comaroff

(2005:23-24). Bessant who was cited in ‘Rethinking Youth’ (1997:18), discussed the popular dual representations of young people both as a threat and the utopian ideal of hope although vulnerable and Comaroff and Comaroff (2005:24) argue that for the most part the everyday lived perception is that ‘youth’ are unruly and constantly challenge the status quo in negative ways.

Here-what is important is the interaction between the constructions of ‘youth’ and policy interventions. It is trite to say that the way ‘youth’ are seen will impact directly with the ways the state or society at large tend to interact with young people. Thus, if ‘youth’ is synonymous with criminality and delinquency, policy interventions will tend to be repressive, invasive or as in our case preventative. To counteract this, Durham (2000:116) contends that young people should be seen as ‘social shifters’ who move between these dual constructions in their lived

34

realities exposing power relations, social structures and the spurious demarcations of who

‘youth’ are. Policy analysis and design however usually fails to appreciate the nuances of young people’s lives in such a way.

Additionally, policy can itself demarcate young people in various ways and may not only be responses to social constructions but can also produce discourses around young people. Jones

(2009:3) notes “it is policy legislation above all else which defines life stages mainly by age and designs provisions accordingly, because age is amenable to measurement”. For example, in the

National Census of Trinidad and Tobago, the National Government (CSO, 2000-2010) adopts the

UN definition of youth. However according to the CSP ‘youth’ are persons between the ages 7-

24, (CSP website, 2009) an even wider group than that adopted by the National Government.

It can be argued that the widening of the age category of youth is a clever tool to legitimize intervention on the part of the government into the lives of young people at an even earlier stage than before. But not only does policy define life stages but it attaches characteristics to those within that age group and labels them as explained below.

A manifestation therefore of these discourses about ‘youth’ is labeling. Thus when labels are affixed to the young men of Beetham Gardens it says a lot about how society perceives this group. The situation becomes tenuous when the young men have already experienced labeling in some regard due to the low status of their community. This ‘double labeling’ as I call it, will only serve to reinforce existing processes of marginalization and result in the inclusion of young men into society in very unequal ways.

History of Labeling and Stereotyping

During my interviews, all of my research participants including members and non-members of the community all commented on the ways in which the Beetham is described by persons of the wider society with whom they have had contact. When asked about his personal encounters with regards to the perception of people of his area, Randy, a 32 year old male resident of the Beetham Gardens says the wider society looks at Beetham “as one of the worst

35

…the most dreadest place. If you go there (Beetham) you go dead...the most baddest, weirdest

most disrespectful set of things people have to say” 12 .

(Interview 1 on 27/08/2012 with Randy 32, male)

Randy recalls Beetham residents being referred to as pests, as criminals and as persons who should be killed, with such statements being made by his work colleagues, persons calling into radio stations and commuters with whom he shared public transportation 13 .

Rhino, a 17 year old male resident, recounts

“ people think all Beetham people are bad, dangerous, criminals.”

(Interview 1 on 28/08/2012 with Rhino, 17 , male)

“Not everybody on the Beetham bad ...it have people who could change their life.

Everybody done thinking everybody on the Beetham is a criminal.”

(Interview 2 on 29/09/2012with Rhino 14 , 17, male)

When pushed further another participant who lives in the community, Jerome, a 19 year old male resident, states that if I were to come and live in the community for a week that I too would become ‘bad’ 15 .

Rex adds

“When I was in primary school …other children would say ‘o god is Beetham rats’…everything you could be eating is from the la basse 16 ”

(Interview 1 on 27/09/2012with Rex, 19, male)

12 Quote from Interview 1 with Randy,27/08/2012.

13 Notes taken from interview 1 with Randy,27/08/2012.

14 Rhino chose his own pseudonym as this issue was brought up on the last meeting with my participants and

Rhino was one of two persons who showed up for the meeting.

15 Notes taken from interview with Jerome,28/08/2012.

16 The La Basse is a Patois word which connotes lowness and is a colloquial term for the dump.

36

This sentiment was a common thread throughout all of the interviews I conducted. Some of the adjectives used to describe the persons living within this community was ‘bad’ and ‘criminal’ recurring the most and insinuations of dirtiness. This correlation of Beetham residents to negative characteristics is well known throughout the wider society and is inextricably linked to the fact that the community is located between the National Dumpsite and an industrial estate.

In 2011 the current Government of Trinidad and Tobago implemented a nationwide State of

Emergency to curb crime 17 . However, the curfews were implemented in most of the communities which were also identified as “high needs” and with rising levels of crime. During this time, persons of these communities who were found violating the state of emergency were detained and imprisoned. A resident of the area highlighted how young men from the Beetham

Gardens are constructed by the state in a newspaper article. The resident noted:

If this state of emergency continues another three months, there might be nobody in Beetham because every day, police holding people. Every male under

30, they label gang member...God, not everybody bad here!

(Quote taken from newspaper article, Alexander, 2011).

In this quote this resident reveals the way in which young men from Beetham Gardens are perceived as bad and perpetrators of crime by the state.

In 2008, a new label was introduced to refer to this group of people. The Government of

Trinidad and Tobago, joined several other countries in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region when it introduced the “at risk” discourse into the national arena via the implementation of the Inter American Development Bank (IDB) programme called the Citizen

Security Programme (CSP). This programme promotes discourse of risk and labels young people as “at risk”.

17 Further information on why the State of Emergency was implemented can be found here http://www.news.gov.tt/index.php?news=9020

37

This label has become increasingly synonymous with young men. Surprisingly however, during my interviews with my young participants, when asked about the term “at risk” none of them recognized it or understood what it was supposed to mean in relation to them. They did identify with the labels of ‘criminal’ or ‘bad’ as discussed earlier. Although this appeared peculiar at first, I argue that failure to identify with this term does not negate the fact that this label effectively reinforces their marginalization. Whether aware of it or not the labels of the

CSP was productive. The effects of the term “at risk” on the public and the consequences it has for these young men’s full participation in society warrants its deconstruction. This label legitimizes increased surveillance of these young men whether they identify with the label or not and presents them as one homogenous group sharing certain negative characteristics.

Who is an “ at risk” youth’?

In an interview with the Ryssa Brathwaite Tobias, the Community and Youth Specialist for the

CSP, an “at risk youth” was defined as follows:-

An at-risk young person from our experience would be one who may or may not have completed school, someone who may or may not have both parents, someone whose household conditions may be deplorable or unacceptable including unsanitary; someone who has been or [is] in contact with the law or whose parents may have been in contact with the law; someone who has witnessed or has been a victim of a crime; any form of victimization; has lost a relative or observed the death of a relative through violence and that’s generally it…and exposure to drugs

(Interview with Ryssa Brathwaite Tobias,

Community and Youth Specialist, CSP, 29/08/2012)

When pushed further about whether the CSP required a convergence of those risk factors to determine if a person was in fact “at risk”, the response was no. Ryssa responded that the CSP looked at:

38

the presence of these risks in the community at general as making you at risk.

The presence of limited access to resources, social services, no state presence, plus those other things. The crime data tells us that its at risk but we don’t set about to measure the level of risk at an individual level because generally you would find that our work is not as yet or as much as we would like it to be at that level of individual level outcomes, more at a community level or at a family level.

We don’t even measure per family risk at this time.

(Quote from interview with Ryssa Brathwaite Tobias, 29/08/2012)

I pushed further with Ryssa, to determine then whether all young people who lived in the communities identified by the CSP were deemed to be “at risk” and the response given was less than clear. She indicated that the CSP did not seek to paint the community with one broad brush and therefore the role of the CAO was important in identifying those who were most “at risk”.

The issue of targeting here remains unclear. On the one hand this definition is clearly quite broad and vague and could essentially include a vast cross section of the population of young people in Trinidad and Tobago. An examination of the actual practices surrounding targeting would suggest otherwise however. The CSP through various methods have concluded that there are 22 high needs communities which contain “at risk” youth. Here we see a tension between programs, their targeting mechanisms and practices.

One possible interpretation of Ryssa’s responses could be that it is a case of political correctness attempting not to explicitly say that these young men are in fact “at risk”. But what this does is then homogenize a large group of people based on their location in a ‘high needs’ community. The issue of spatial dynamics arises here again. Risk only becomes problematic when it is located in a community defined by the CSP as ‘high needs’.

Randy, a 32 year old male resident was asked what he thought about the label of “at risk” to which he responded that he couldn’t understand its significance because the youths “at risk”

39

were everywhere.

18 This tension of who really is “at risk”; its apparent applicability to a wide cross section of people yet only actually applying to some young people leads us to our discussion on the dangers of this label as it poses several difficulties including but not limited to: individualization, the linking of “at risk” youth to crime and delinquency as well as homogenization and gender stratification. Our deconstruction becomes even more complex when a positive aspect is highlighted during one of my interviews and will be explored in the next chapter.

Individualization and the Deficit Model

Although it appears that ‘at risk youth’ as defined by the CYS officer could apply to a broad cross section of young people within the Trinidadian context and not necessarily limited to those in the so called ‘high needs’ communities, such as the Beetham gardens, the fact remains that only certain sites are the recipients of this label despite this very broad categorization.

Te Riele (2006:138) in her work on young people at risk of failing within the school system makes the following statement:-

The very act of identifying some subgroups of students may be interpreted as locating the problem in those students themselves and thus ‘blaming the victim’ (Natriello et al., 1990, p. 3). Taylor (2002, p. 512) suggests that labelling a young person as ‘at risk’ implies ‘a flawed moral biography’.

Identification may lead to lowered expectations, decreased self esteem, and de-motivation, all with possible detrimental effects on students’ educational achievement...

What Te Riele is describing is known as the deficit model, whereby young people who are labeled as “at risk” are perceived as lacking some essential qualities and risk is seen as an individual attribute (Te Riele, 2006:136) or even a group attribute.

18 Quote from interview on 27/08/2012 with Randy.

40

What this label of “at risk” does therefore in the present context is identify the young men in

Beetham Gardens as being flawed, blaming them because they have a propensity to participate in criminal activity from which they must be deterred.

Te Riele suggests that more complex interpretations which consider macro structural processes for example income inequality or labour market biases, of risk are rare (2006:136). In a speech given by the Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago at the launch of another government intervention in the Beetham Gardens, the Making Life Important Initiative (MLI) she listed such factors which contribute to crime as:

Poverty and inequitable distribution of wealth and opportunities; High levels of unemployment; The collapse of supportive family structures and social

relationships; Inadequate schooling; The proliferation of street gangs which offer nurturing, protection, friendship, emotional support, and other distractions

for unattended, unchaperoned resident youth; Lack of positive role models for

the youth to emulate, in particular “father-figures”; and Physical environments and spaces which have negative impacts on human behaviour – the “Broken

Window” Syndrome which suggests that broken windows and smashed cars are visible signs of people not caring about their community and which may give out

crime-promoting signals.

This acknowledgement of external and structural factors was juxtaposed against a previous statement in that same speech:

Earlier this year, there was the launch of the National Youth Mentorship programme, another flagship initiative under the Ministry of National Security I recall saying that “we will never be able to turn around our crime situation unless at-risk youths are given the opportunity to change the stigma that is attached to them( my emphasis)

(Excerpt from Speech at launch of MLI Initiative, Bissessar,2011).

41

What this effectively does is, simultaneously label young people as “at risk” then tell them that they are the ones responsible for changing that label.

Another example of this individualization was seen at the launch of the CSP, where the CSP was described as: an interactive pro social intervention, which seeks to identify at risk-youths, and provide them with positive alternatives, so as to change their negative behaviours

towards society (my emphasis) and stop this cycle of spiraling violence and crime.

(Excerpt from speech at launch of CSP given by

Minister of National Security, 2008).

The underlying assumption is that the problem lies with the young people themselves. Laying blame within the individual makes it easy for young people to become the ‘criminal other’.

Swadener and Lubeck (1995:69) in their discussion of mothers “at risk” state that the blaming of individuals “provides an easy, relatively powerless target for public scorn of (“Them”) and allows (“Us”) who are neither poor, unmarried, divorced, minority, nor working in a job that provides little flexibility to be self-congratulatory”. This distinction she adds makes it clear who has the right to speak and who is to be spoken of and relieves ‘us’ of any obligation to listen to

‘them’ (Swadener and Lubeck, 1995: 69). Laying the blame on the individual can in itself exclude groups of people who are seen as incapable of making the right prescribed choices.

Linking Young People to Crime and Delinquency

According to the Community and Youth Specialist (CYS) of the CSP, these categorizations of

“high needs” and “at risk” are based, inter alia upon statistical crime data which have indicated that the targeted communities experience high levels of crime 19 .

19 Notes taken from Interview with Ryssa Brathwaite, 29/08/2012.

42

The CSP was designed to “create a culture of peace and lawfulness” (CSP Trinidad and Tobago website) and is focused on deterring young people from lives of crime; crime being the purported major risk that young people face within the Beetham Gardens.

Peetz (2011:1465) argues that:

When we categorize an act as juvenile delinquency or youth violence, we pick one of the many aspects of a given deed and define it as the distinctive one. Apart from the fact that the act is considered criminal or violent, the age of its perpetrator becomes the crucial characteristic by which to classify it.

According to Buvinic et al (2005:4) in their report ‘Emphasizing Prevention Citizen Security: The

Inter American Development Bank’s Contribution to Reducing Violence in Latin America and the

Caribbean’ :

The most compelling data at the macro or societal level links the high levels of violence in the region, first, with the demographic transition that has boosted the segment of the population that is most prone to aggression (youths). Second, there is a significant relationship between violence and the region’s historically high and still growing income inequality.

Buvinic et al add further that (2005: 15) “a large percentage of youth in Latin America and the

Caribbean are at high risk of engaging in dangerous behaviors such as association with gangs or other high-risk peer groups, alcohol and substance abuse, and violent behavior”.

Under this discourse young people are seen as threats to the security of others as they are perceived as “prone to aggression” (Buvinic 2005:4) and highly vulnerable to participate in criminal activity.

Homogenization and Gender Stratification

Labeling young people in the Beetham Gardens as “at risk”, bad or criminals homogenizes all young people in this area as deviants. According to Jones (2009:3-4) it is a clear manipulation to refer to young people as one social unit, a homogenous group which fails to acknowledge the

43

heterogeneity and diversity amongst young people and their experiences. It fails to consider the structural inequalities, agency and marginalizing effects of labels.

Swadener and Lubeck (1995: 76) present this as a ‘shaved or partial image of those who are defined as at risk’. Framing therefore highlights one aspect of a reality while leaving out other, equally important aspects; giving the effect of a skewed reality to wider society (what is being left out of this at risk discourse is explored below). According to Te Riele (2006:140) the label of

“youth at risk” can result in further marginalization of young people and takes emphasis away from policy responding to the real needs of the target group.

Furthermore, the nexus between crime and youth is not the only one being made but in fact the link is made between young men and participation in criminal activity. According to the

Caribbean Human Development Report 2012 (2012:47) in which they surveyed the entire LAC region, they found that: youth violence has a gender dimension. Across the region, the majority of aggressors and victims are young men who use violence for protection against threats—real or perceived—or who have been socialized into a male-dominated tradition of conflict resolution through violence. At the same time, young women are victims of verbal and physical violence, particularly in the interpersonal and domestic spheres. Relative to men, almost twice the proportion of women reported being threatened by spouses, partners, or ex-partners (14 percent of young women compared with 7.5 percent of young men).

Young males increasingly come to be known as perpetrators of violence and crime becomes synonymous with juvenile offending by young males; whilst women are the victims.

According to the Children and Youth Specialist, gender mainstreaming is not the intention of the CSP however and there was an attempt to engage in programmes which both males and females could participate in 20 . However when asked whether the programmes tended to attract more males than females, the Children and Youth Specialist stated that:

20 Notes taken from interview with Ryssa Brathwaite Tobias on 29/08/2012.

44

[…] part of it is coincidental , because some of the most effective ways of mobilizing communities are kind of male oriented such as football …deejaying… lets say steelpan 21 and this tends to appeal to a male audience so I think part of this is coincidental, part of it is deliberate based on who’s holding the guns…

(Quote taken from interview with Ryssa Brathwaite- Tobias, CYS , 29/08/2012)

Although the gender mainstreaming may not be intentional, the CSP may be gender blind in its approach and this can be viewed as one of the unintentional effects of policies that Li (2007) talks about in her article on governmentality. One view may be that it is erroneous to think that girls do not participate in activities which are viewed as male centric such a sports or that the implementation of such programmes succeeds in excluding young females from participating on a larger scale 22 . Further research on young women’s participation is clearly needed in this area.

Either way, the acknowledgement that some gender disparity does exist gives credence to the

Caribbean Human Development Report’s finding that ‘youth violence’ is gendered and should be subjected to further research.

Whilst the data may indicate that violence is gendered, it does not negate the fact that labeling an entire group of young men as “at risk” is grossly homogenizing and discriminatory against young men from this community. If all young men are perceived as deviants then this affects how society, international organizations and the state (including the police and the judiciary) interact with these young men and this leads to our discussion in the next section about technologies of governance.

Risk discourses and labels individualize young men and pathologizes them into following criminal careers. These labels however compound previous labels of ‘criminals’ and as ‘bad’.

21 The steelpan is a musical instrument created in Trinidad and Tobago.

22 A request was made for a list of programmes for the year 2012 and the gender of their participants from the CSP and although the CSP indicated their willingness to provide same no data was received at the time my paper was finalized.

45

This double labeling can only serve to reinforce these previous labels which reflect some of the processes of marginalization of young men.

Garnering Interest, Creating Linkages and Partnerships – the positives of the label

But the label may not be all bad depending on where the subject who is discussing the label is situated. According to the Children and Youth Specialist, this label can be beneficial:

Question: - Does society’s view of the Beetham impede the CSP’s work?

Answer:- The positive that comes is that everybody has a desire to demonstrate that they can work in Beetham. We get a lot of opportunities to partner and bring stakeholders in…you must be the 3 rd or 4 th student with an interest in working in Beetham that we have encountered. The rotary club, the lions club there are a lot of external agencies who want to work in the Beetham and some of them just don’t have a point of entry and so it makes it easy for us because there are some things we can’t do and there are other agencies able to do it and willing to do … I would say that it doesn’t impede it in that sense. How it might impede it might be where sometimes we have situations where, like an employment situation…for a lot of them the presented issue is one of bread and butter, so ...employment partners, people interested in employing people might say …because you are a legitimate organization, we are willing to hire these young people to get them to do something else and then they might realize where the young people are coming from and it may affect some of the opportunities that would be facilitated for the community…but from where I sit it appears that there are a lot of partners and a lot of opportunities for the community based on it being Beetham Gardens and everybody is willing to conquer it

Question: - In a sense the at-risk discourse actually helps?

Answer: - it makes it attractive it makes it a sexy community to work in.

46

(Excerpt from interview with Ryssa Brathwaite Tobias,

Community and Youth Specialist CSP, 29/08/2012)