LEOTC in a regionally-focused environment

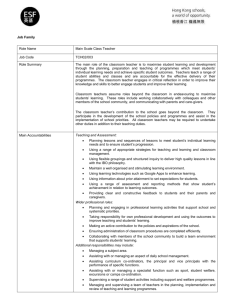

advertisement