Floods, storms, natural disasters and how they shaped cities in the

advertisement

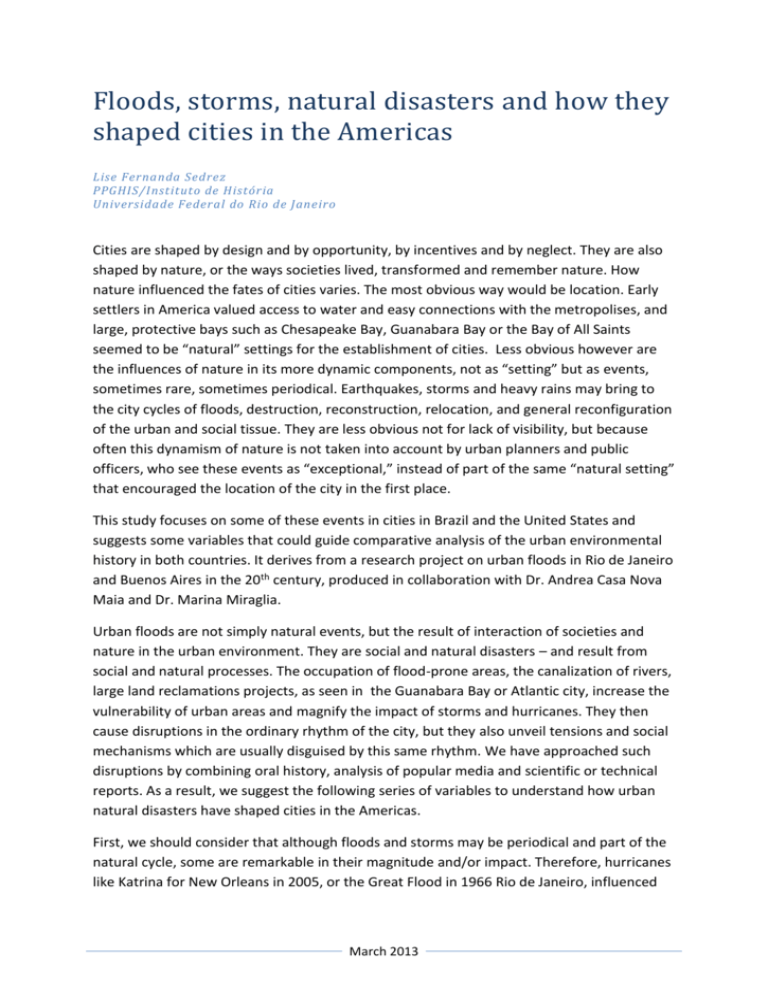

Floods, storms, natural disasters and how they shaped cities in the Americas Lise Fernanda Sedrez PPGHIS/Instituto de História Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Cities are shaped by design and by opportunity, by incentives and by neglect. They are also shaped by nature, or the ways societies lived, transformed and remember nature. How nature influenced the fates of cities varies. The most obvious way would be location. Early settlers in America valued access to water and easy connections with the metropolises, and large, protective bays such as Chesapeake Bay, Guanabara Bay or the Bay of All Saints seemed to be “natural” settings for the establishment of cities. Less obvious however are the influences of nature in its more dynamic components, not as “setting” but as events, sometimes rare, sometimes periodical. Earthquakes, storms and heavy rains may bring to the city cycles of floods, destruction, reconstruction, relocation, and general reconfiguration of the urban and social tissue. They are less obvious not for lack of visibility, but because often this dynamism of nature is not taken into account by urban planners and public officers, who see these events as “exceptional,” instead of part of the same “natural setting” that encouraged the location of the city in the first place. This study focuses on some of these events in cities in Brazil and the United States and suggests some variables that could guide comparative analysis of the urban environmental history in both countries. It derives from a research project on urban floods in Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires in the 20th century, produced in collaboration with Dr. Andrea Casa Nova Maia and Dr. Marina Miraglia. Urban floods are not simply natural events, but the result of interaction of societies and nature in the urban environment. They are social and natural disasters – and result from social and natural processes. The occupation of flood-prone areas, the canalization of rivers, large land reclamations projects, as seen in the Guanabara Bay or Atlantic city, increase the vulnerability of urban areas and magnify the impact of storms and hurricanes. They then cause disruptions in the ordinary rhythm of the city, but they also unveil tensions and social mechanisms which are usually disguised by this same rhythm. We have approached such disruptions by combining oral history, analysis of popular media and scientific or technical reports. As a result, we suggest the following series of variables to understand how urban natural disasters have shaped cities in the Americas. First, we should consider that although floods and storms may be periodical and part of the natural cycle, some are remarkable in their magnitude and/or impact. Therefore, hurricanes like Katrina for New Orleans in 2005, or the Great Flood in 1966 Rio de Janeiro, influenced March 2013 the history of their cities not only due to the number of victims or the degree of destruction, but also due to the way the city will remember them, how they will shape the city’s identity and expectations of their residents. Second, the city is not affected evenly in all its areas. Some areas are more dramatically disrupted than others, and they are fixed in the memory of the residents as symbols of the disaster, as for instance, the Superdome in New Orleans or the Praça da Bandeira in Rio de Janeiro. They are, in some ways, places of environmental memory. These iconic places are defined in many different ways: because of their centrality to transportation, because of their dramatic image in the moment of disaster, because of the number of victims, or because of what they represented to the city in more ordinary circumstances. Third, disasters bring to attention the role of the state - whether it is at local or national level depends on the magnitude of the disaster. We here consider not only what governments did (or neglected doing) in planning the cities and preparing for disasters, but also what are the expectations of the population regarding the role of the state. It is also important to take into account the action of non-state institutional actors, such as churches and newspapers, in mobilizing local residents and challenging or complementing the action of the state. Fourth, concepts of class, race and gender contribute to understand how society reacts to the disasters, makes decisions (such as whether to evacuate or not, or the establishment of solidarity networks, and even the level of public alarm regarding future events). Fifth, the aftermath of a natural disaster is a critical moment of restructuration of the city and of society itself. It may also be a moment of some empowerment for vulnerable communities and individuals, which define strategies of survival and mobility, seizing the uncommon attention they obtain. What happens to these communities, where they are placed, or how they relocate, may define the future development of the city, as it was the case with Cidade de Deus in Rio de Janeiro, and it reveals much about how the urban growth changes surrounding green areas. These variables are by no means exhaustive, and they draw heavily on the carioca experience. They are based on the premise that natural urban disasters are not exceptions, but part of the urban historical narrative. It is in this sense that they offer a challenging, although tentative, framework to understand the dynamic relation of city and nature, in both countries. March 2013