Vertical Leadership Development: Reframing Organizational

advertisement

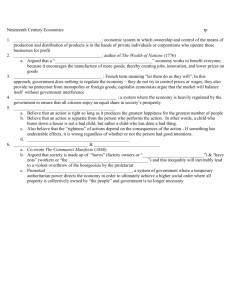

Vertical Leadership Development: Reframing Organizational Change by Reframing Meaning Making Greg Gifford, Ph.D. Federal Executive Institute United States Office of Personnel Management Overview Vertical leadership development challenges the existing notion that leadership development is simply a progression of knowledge and skill development coupled with the application and refinement of those skills. It goes beyond the competency-based or “horizontal” developmental approaches to explore the way in which leaders learn to construct meaning from experiences so that they can apply their competencies more effectively to achieve both individual and organizational change. Background The U.S. Office of Personnel Management specifies 28 leadership competencies. 22 Of these support five Executive Core Qualifications (ECQs) the other six are “fundamental competencies” that basically support all of the ECQs. The arrangement of these competencies appears below: Figure 1: OPM’s ECQs and Leadership Competencies While immensely powerful in describing specific leadership skills and behaviors many theorists within the leadership-development industry have begun questioning the effectiveness of competency-based approaches. George Hollenbeck, writing for the Center for Effective Organizations, has argued, 1 [E]vidence abounds that executive and leadership development has failed to meet expectations. Unless we change our assumptions and think differently about executives and the development process, we will continue to find too few executives to carry out corporate strategies, and the competence of those executives available will be too often open to question. The “competency model” of the executive, proposing as it does a single set of competencies that account for success, must be supplemented with a development model based on leadership challenges rather than executive traits and competencies. Executive performance must focus on ‘what gets done’ rather than on one way of doing it or on what competencies executives have. In turn, executive development must be viewed as meeting performance challenges essential to the business strategy rather than attending development programs, with senior executives making development decisions much as they make business decisions today. This “post-competency” movement is gaining ground in the leadership development and change management field. To understand its proponents’ argument, imagine that the competencies – those specific skills so vital to leadership success – are bricks. One can improve the quality of bricks but doing so does not necessarily result in a superior structure. Great bricks can be used to make beautiful cathedrals or palaces, but they can also be used to build barbeque grills and outhouses. The postcompetency proponents argue that what are most important are not the bricks themselves – although they concede the bricks must be of high quality – but what we do with those bricks. In terms of leadership development and change, it is not the individual skills and abilities but how they are employed to achieve results. To make that transition from skill building to skill-employment, however, one has to think differently. Vertical leadership is an emerging theory designed to do just that: change the way that leaders conceptualize their world. Vertical Leadership Explained In their book, Transforming Your Leadership Culture, John McGruie and Gary Rhodes argued: Organizations have grown skilled at developing individual leader competencies, but have mostly ignored the challenge of transforming their leader’s mindset from one level to the next. Today’s horizontal development within a mindset must give way to the vertical development of bigger minds. Instead of focusing on the development of knowledge, skills and abilities, organizations and agencies may seek to provide developmental opportunities and experiences that challenge leaders with developing their world-view and how they make sense of the world around them (Figure 3). In much the same way that young children are exposed to a variety of situations, people and experiences, leaders also benefit from exposure to such variety. Unlike life experiences of young children, however, vertical leadership development experiences are coupled with reflection and purposeful learning environments to expose these leaders to different ways of constructing meaning and making sense of the experience. By engaging in this process, these leaders expand their minds and views of the world. This is in stark contrast to their simply having their minds filled with new knowledge, skills or abilities. It is the difference between filling a glass with water (horizontal development) versus grasping the myriad ways in which the glass and captured water might be repurposed. It is the difference between providing and refining bricks and the ability to conceptualize how those bricks might be arrayed to build required structures. Constructive Development 2 That leaders are made and not born – that it is “nurture not nature” that creates leaders – suggests the notion that individual development occurs over time. Early researchers argued that by the time human beings reached early adulthood (mid-twenties) the mind was fully developed. Later research debunked this notion and showed that the mind continues to develop throughout adulthood with periods of growth and periods of stability. Robert Kegan, the Associate Director of Harvard's Change Leadership Group and a founding principal of Minds at Work, conceptualized adult constructive developmental theory as the way in which adults “make meaning” of the world around them. Depending on their stage of constructive development, people will construct meaning of situations, persons, events and interactions differently. Perry (1970) stated that over the course of their lifetimes, people derive situational understanding based upon the manner in which they construct meaning and are able to organize and synthesize interpersonal interactions. Constructive development focuses not on what people know, but how they know what they know (Piaget, 1972). Experiences & Meaning-making Competencies: Knowledge, Skills and Abilities Horizontal Leadership Development Figure 3. Vertical Leadership Development versus Horizontal Leadership Development In his book, In Over our Heads, Kegan argued that most adults face challenges and situations that are beyond their developmental understanding—this includes leading organizational change. Most adults have not fully developed the cognitive, moral and social development needed to make sense of an increasingly complex world. In fact, Kegan argued that this is the reason why so many executives fail in their careers and also fail in leading change processes. Most training and development programs are competency-based programs, focused on specific skills. The participant attends a training class and learns how to apply a skill or set of skills to one or more situations. Training programs are essentially programming new software – new applications - into existing computer systems. Change efforts are similar and tend to be more rearrangement than rethinking or reformulation. Adult constructive development theory posits that instead of simply loading new applications, the computing system needs to be upgraded or reimagined. Leader developmental opportunities and organizational change initiatives should focus on how to think and process differently (e.g.—how to construct meaning) to approach 3 situations and challenges from a more complex cognitive, moral and social paradigm rather than simply applying a new skill or tool from the person’s existing paradigm. Kegan conceptualized five stages of development of the mind ranging from Stage 1 which is applicable mostly to young children to Stage 5 which transcends ego, embraces ambiguities, applies to very few adults and it not yet fully understood. Garvey Berger (2006) suggested that Kegan’s stages fit into adult constructive development because the theory outlines how adults both construct reality and then develop to more complex levels over time based upon their individual constructions. It is important to understand the level of cognitive development of leaders who are undertaking change efforts in organizations. By creating this understanding, the impact of the organizational change effort can be more fully understood. A leader at lower levels of cognitive development is likely to have less complex change initiatives than those at the upper levels of development. Each of Kegan’s stages is a progressively more complex way of making meaning than the previous stage. As adults move through the stages of development, what was learned in previous stages is not left behind but informs and contributes to meaning making in subsequent levels. For example, when children learn to run, they do not forget how to walk. When they learn to ride bicycles, they do not forget how to run and walk. Garvey Berger (2006) stated that no level of development is inherently better than a previous level but instead each level is in essence a qualitative description of an individual’s way of making meaning. She continued by stating that “people can be kind or unkind, just or unjust, moral or immoral at any of the [levels] so it is impossible to measure his or her worth by looking at his or her [level] of the mind (p. 3).” Subject & Object. Vital to the understanding of Kegan’s Stages of Adult Development is the movement from subject to object. For Kegan, when people are subject to something (situation, person, moral, value, etc.), that something is a part of them without their awareness of it. People experience the subject without questioning its status, correctness or applicability. Generally, things that people are subject to are taken for granted and considered to be truth. Kegan (1994) described those things that we are subject to as “those elements of our knowing or organizing that we are identified with, tied to, fused with or embedded in (p. 32). By way of example, consider primitive man’s understanding of the world. It was a flat Earth and man understood that the only way to avoid catastrophe was to stay very near shore, avoiding the twin perils of falling off the edge or being consumed by the great sea serpents that thrived in the deep waters near the edge. Mankind understood this as its reality; it was subject to these natural limitations. Those things that are considered to be object are the opposite of subject. Similar to physical objects that we can pick up, analyze, play with and move from space to space, those things that are objects in our mind (e.g.—relationships, traits, beliefs, values, etc.) can be analyzed, applied in different situations, considered for accuracy and truth, and controlled. Kegan (1994) argued that “…those elements of our knowing or organizing that we can reflect on, handle, look at, be responsible for, relate to each other take control of, internalize, assimilate, or otherwise operate on” are those things that are considered object to us (p. 32). Returning to the flat-earth example above, as voyagers ventured further from land they had to reinterpret the boundaries to which they were subject in the past. New understandings removed those barriers making them object – subject to consideration and reinterpretation. Much of scientific discovery throughout mankind’s history has been a similar reimagining from subject to object. Myths and “old wives’ tales” have been replaced by science; former boundaries and frontiers have been reimagined as 4 merely passageways to new lands, new heights, new depths … new worlds. Much as mankind as grown as a species, Kegan argues we grow as individuals. As people progress through the stages of development, those things that they are subject to become object to them. That is, things that have people – that people are subject to, such as values, traits and ideals, can move from a blind acceptance to an understanding that people have these things and can emphasize, orchestrate, organize or even change them to fit their individual contexts. At this level of realization, subjects become objects; objects that can be analyzed, tweaked, applied differently and considered for truth and accuracy. Further, as these subjects become objects, people begin to construct meaning in different and, sometimes, profound ways. This shift from subject to object is the nucleus of the development underpinning Kegan’s Stages of Adult Development and is a vital component in both individual and organizational change. Kegan’s Stages of Adult Development. In his work on the subject, Kegan delineates transformation in meaning making into five, distinct stages. These stages represent the development and growth of the mind from early childhood through late adulthood. Kegan suggests that most adults will not progress through all of the fives stages but will stop at a specific level of advancement; an assertion born out in subsequent research. Nevertheless, understanding the five stages can be valuable in establishing the kinds of developmental opportunities executives need in ensuring their agencies have adequate numbers of new leaders emerging within their workforces. Kegan’s five stages of development are as follows: the Impulsive Mind, the Instrumental Mind, the Socialized Mind, the Self-Authoring Mind and the SelfTransforming Mind. The Impulsive Mind. Children between newborns and seven years of age are typically categorized as being in the impulsive mind level of development. The impulses are subject to these individuals because they do not understand their impulses and therefore cannot control them. For example, if a child is given a cookie and asked them not to eat it until later, when they are especially hungry, most children will feel the hunger impulse immediately and devour the cookie without hesitation – often only to be hungry later! At this level of development, where impulses control behavior, the individual requires regular – if not constant supervision. The Instrumental Mind. Children between the ages of 7 to 10 years old, some adolescents and some adults are categorized as being at this level of development. Beliefs and meanings become object to individuals in this stage as they realize that they have beliefs and feelings that remain constant over time. Individuals at this stage are also aware that others have beliefs and feelings; however, the instrumentalminded individual is not empathetic to these differentiated beliefs or feelings. Because the person at this stage is typically self-centered, the beliefs and feelings of others become simply aids or hindrances to the individual’s accomplishment of self-interest actions. The Socialized Mind. In this category we find children aged 10 and older as well as most adults. In this stage, individual desires and impulses (which were subject in the Instrumental Stage) have now become object. Individuals at this stage develop an ability to subjugate their own impulses and desires to the desires of others. Subject to individuals at this stage are the feelings and emotions of others, particularly those guided by institutions that are most important to the individual (i.e., school, religion, political party affiliation, community groups, etc.). Individuals at this stage are able to reflect on their own actions and the actions of others and have put aside selfish impulses for the good of valued 5 institutions. Individuals at this stage, however, cannot distinguish their own wants and desires from those institutions that have shaped their wants and desires. Esteem at this stage is not self-esteem but is instead reliant on the judgment of others. Because of this, individuals at this stage will struggle when there is a conflict between two or more important others. When conflict occurs between competing interests, the individual will feel “torn in two” and will be unable to come to a decision easily – if at all. Subject to the person at this stage is that the definition of self is created in relation to the people and institutions that the person values. The Self-Authoring Mind. This stage includes some of the adult population but exact estimates vary. At this stage, the influences of people and institutions become object to individuals. A person in this stage has developed a value system that is truly their own. It can be defined outside of existing relationships and institutions. A person in this stage of development can examine and analyze rules, systems, opinions and thoughts of others, compare those things to their own self-authored value system and then determine the worth of the input they receive from others. Individuals no longer feel torn between conflicting inputs because they have developed their own internal governing system to understand conflicts and reach decisions. Individuals at this stage are self-motivated and self-directed. They “author their own life stories” as they go. They can belong to institutions or groups without being defined by or engulfed into those groups. Despite this seemingly advanced level of development, however, individuals at this stage may struggle contrasting situations that are right and right decisions. Further, individuals at this stage often encounter limitations because their self-authored guidance systems are subject to their individual and it becomes difficult to appreciate the self-authored or institutionally guided system of others. The Self-Transforming Mind. Less than 1% of the adult population has reached this level of development and, because there are fewer people at this level, much less is known about it. Kegan (1994) argued that individuals at this stage develop their own process for making meaning but simultaneously realize that their own process is flawed. They see limits in their values systems and are therefore open to ambiguities. They view the world in “shades of gray” with far more similarities than differences and much more connectedness than disparity. While at level four, the self-authored system is subject to the individual, at level five, the system is object and thus can be explored, manipulated, reset and applied differently in different situations. As individuals progress through the stages of development, worldviews move from simple to complex and unfold in increasingly dynamics ways. Self-centeredness takes a backseat to concern for others and institutions which are, in turn subordinated to a greater world-centric connectedness. While individuals move consecutively through the stages (stages are not skipped), most adults will spend some time transitioning from one phase to the next. Thus, analysis of people’s levels of development is likely to show elements of more than one of the levels at any given point in their lives. While none of the stages are considered to be better than the others, the important challenge is to determine if the level of development is appropriate to contextual requirements particularly during times when organizations may be invoking change. Development of the mind is an interchange between both individuals and the environment in individuals live and work. Managing the Change Process 6 While horizontal development is often learned by imparting knowledge to an individual from an expert, vertical development is a combination of skill use and self-learned development (Petrie, 2009). Moving from one level to the next level often occurs when an individual finds limitations or faults with their current way of making meaning - dissatisfaction with their current stage of development (Garvey Berger, 2006). Kegan and Lahey (2009) suggested that in order for people to move from one stage to the next, they must be able to move assumptions from subject to object and then to test the validity of their assumptions. Facilitators may be able to assist in this learning process but only if people are open to such learning. Kegan (2009) argued that there are four reasons that cause individuals to move from one stage to the next: The person feels consistently frustrated by a situation, dilemma or challenge in life This situation, dilemma or challenge causes a person to feel the limits of their current way of thinking The situation, dilemma or challenge occurs in an area of life about which the person cares deeply There is sufficient support available as the person progresses through anxiety or conflict. Once individuals are ready to move to the next level, steps must be taken to surface those things that are subject in one level and object in the next level. This is critical to consider when organizations engage in large scale change processes. McGuire and Rhodes (2009) described this process in three steps: awaken, unlearn and discern, and advance. Awaken: the person becomes aware that there is a different way of making sense of the world (or situation) and that doing things in a new way, based on the new meaning, is possible. Unlearn and Discern: The old assumptions are analyzed and challenged. New assumptions are tested and experimented with as new possibilities for making meaning. Advance: Advancing fully to the next level of development occurs with both practice and effort. The new way of making meaning dominates previous ways of making meaning and this new meaning makes more sense and is more applicable than previous thinking Executives and organizations must be purposeful with their desire to employ vertical leadership development by providing experiences and opportunities, along with support and mentoring that allow leaders to examine the assumptions and views they hold – to move understandings from subject to object. Kegan and Lahey suggest that this purposeful vertical development process could be widespread in organizations. In fact, they suggest that in organizations where vertical development is widespread and apparent any person in the organization could tell you 1) the one thing they are working on that will require their personal growth to accomplish it, 2) how they are working on it, 3) who else knows and cares about it, and 4) why it matters to them. Vertical leadership development combined with horizontal leadership development leads to powerful succession planning for agencies and organizations. Conclusion 7 Kegan and Lahey argued that organizational change must begin with individual change. Executives and organizations must be purposeful with their desire to employ vertical leadership development by providing experiences and opportunities, along with support and mentoring that allow leaders to examine the assumptions and views they hold – to move understandings from subject to object. Allowing and sometimes forcing leaders and others in an organization to move their perspectives from subject to object creates an opportunity to invoke both individual and ultimately organizational change. While leaders often think strategically about change, it is important to consider that organizational changes must include individual change. Kegan and Lahey suggest that this purposeful vertical development process could be widespread in organizations to assist in contributing to change efforts. In fact, they suggest that in organizations where vertical development is widespread and apparent any person in the organization could tell you 1) the one thing they are working on that will require their personal growth (change) to accomplish it, 2) how they are working on it, 3) who else knows and cares about it, and 4) why it matters to them and aligns with organizational change strategy. Vertical leadership development combined with horizontal leadership development leads to powerful change for agencies and organizations. 8