Supplemental Information for the manuscript

advertisement

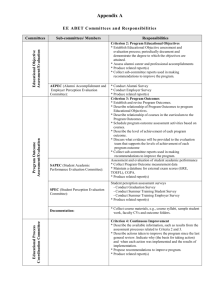

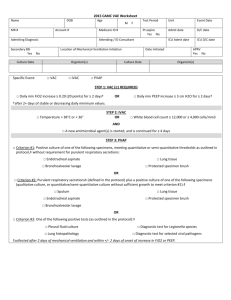

Individual difference in criterion shifting Supplemental Information for the manuscript: Individual differences in shifting decision criterion: A recognition memory study Elissa M. Aminoff, David Clewett, Scott Freeman, Amy Frithsen, Christine Tipper, Arianne Johnson, Scott T. Grafton, & Michael B. Miller Department of Psychology, University of California, Santa Barbara Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies, University of California, Santa Barbara S1 Individual difference in criterion shifting S2 Supplemental Methods: Participants 133 people were designated to participate in this study. 38 of the participants were not used in the final analysis due to the following reasons: 8 did not pass MRI safety screening measures; 4 were claustrophobic; 5 had a technical error in data collection; 20 participants missed more than 40 trials (over 10% of the trials) in either the Words or the Faces test; 1 did not follow task instructions. Procedural Variations The procedure and parameters detailed in the main text was used for a majority of our participants (participants 31-133), however the first 30 participants had a slight variation of the sequence of events and parameters of presentation. Participants 1-17 studied both the faces and the words before going into the MRI. In this case the words were presented for 1 second and the faces for 2 seconds, without an inter-stimulus interval. Participants 18-27 had the same procedure as the first version except an inter-stimulus interval of 500ms was included. Participants 28-30 studied both the faces and words in the MRI, however before both testing sessions. As mentioned in the main text, method variations were always regressed out of the analysis and did not have a direct effect on criterion shifting. Reliance on cue information (RCI) Two raters scored the free response questions with high consistency (Words r: .839; Faces r: .838). The free response ratings between the two raters were then averaged together. The final RCI score was an average of the averaged free response ratings and the ratings given by the participant in the questionnaire (consistency Words r: .646; Faces r: .605). Individual difference in criterion shifting S3 Supplemental Results: Optimal Criterion In the Words test, only two participants reached and exceeded optimal criterion in the High Probability condition, and five participants reached and exceeded optimal criterion in the Low Probability condition. In the Faces task, three participants reached and exceeded optimal criterion in the High Probability condition, and two participants reached and exceeded optimal criterion in the Low Probability condition. No participants reached an optimal criterion shift in both tasks. Criterion Shift Range Criterion shifting ranged from a minimal shift of -.4 for the Words, and -.29 for the Faces to a maximum of 2.81 for the Words, and 2.19 for the Faces. The median criterion shift score was .55 for the Words and .57 for the Faces. There was no relation between the participant’s average criterion across conditions (i.e., their starting response bias) and criterion shifting (Words: r = .006, n.s.; Faces: r = -.161, n.s.). Criterion shifting across the duration of the experiment In the results of this study we analyze criterion shift as a single value across the duration of the whole experiment. However, it is possible that individuals shift criterion more (or less) as the duration of the test increases. In assessing the reliance of cue information, each participant was also explicitly asked whether they relied more or less on the cue as the test progressed. A majority of the participants (45%) said they relied more on the cue as the test went on, mostly due to fatigue and the increase of stimuli interference as the test went on. The remaining participants were relatively split between saying they were consistent throughout the test, and those that said they were less influenced (30%). We suggest these results support the Individual difference in criterion shifting S4 proposal that as task difficulty increases and memory declines, indicated by fatigue and stimuli interference, a greater reliance on the cue information is found. To further examine how criterion shifted across the duration of the experiment, we also analyzed the performance data in sections to compare the first half compared to the second half of the test. Although numerical higher in the second half, there was no significant differences between criterion shifting in the first half compared to the second half of the test (Words: 1 st = .596, 2nd = .661, p = .17; Faces: 1st = .567, 2nd = .652, p = .06). Since each participant performed two sequential memory tests, we also compared the first half of the first test to the second half of the second test. This comparison did not yield significant results either (1st = .571, 2nd = .678, p = .12). Additional reaction time analyses Reaction times for the Faces recognition test were longer compared with the Words recognition test (t(94) = 7.9, p < 10-11). There were no differences between different probability conditions. Reaction time was a variable entered in the categorical regressions, but was not found to have a significant relation to criterion shifting. Reaction time was also compared in the trials in which the probability switched from the previous trial compared with trials in which the probability stayed the same. Participants took significantly longer to respond during the switch trials compared with the same trials (Words: t(94) = 11.10, p < 10-18; Faces t(94) = 9.50, p < 10-14). We compared this difference in reaction time of the switch versus same trials with the amount the participant shifted criterion, or relied on the cue information. Overall, there was no significant relation between difference in RT and criterion shifting or reliance on cue information. However, within the High Shifters there was a significant relation between the amount of criterion shift and difference in reaction time of the switch versus same trials (R2 = .213). Individual difference in criterion shifting Detailed Results from the Categorical Regressions Category Demographic State of Mind Cognitive Style Mental Health Personality Behavioral Variable military rank age gender education handedness scan time arrival time sleep MSW MSF meals caffeine exercise alcohol smoking anxiety physical comfort OSIQ-S OSIQ-O VVQ-W VVQ-P SBCSQ-vis SBCSQ-verb Need for Cognition Paper Folding Card Rotation Vocabulary Working Memory BDI PTSD Concussion (lifetime) Concussion (5yr) PANAS shyness PANAS fatigue PANAS serenity PANAS surprise PANAS positive PANAS negative BIS BAS reward BAS drive BAS fun seeking EPQ-R psychoticism EPQ-R lying Big 5 Conscientiousness Big 5 Agreeableness Big 5 Openess Extraversion Neuroticism RT High Prob. RT Low Prob. Words 0.347 0.028 0.082 0.080 0.034 0.205 -0.445 0.126 0.238 -0.250 -0.115 0.212 0.043 -0.003 -0.148 0.065 0.181 0.043 -0.057 0.077 -0.017 -0.091 -0.092 -0.081 0.360 -0.041 -0.003 -0.027 -0.136 0.300 -0.161 0.235 -0.111 0.137 -0.069 -0.075 0.185 -0.234 -0.027 -0.052 0.063 0.162 0.078 0.028 0.063 -0.132 -0.080 -0.064 -0.008 0.135 -0.208 Faces 0.247 0.251 -0.011 -0.024 0.047 0.088 -0.111 -0.130 -0.085 -0.061 -0.124 0.296 -0.029 -0.266 -0.056 -0.119 0.071 0.068 -0.130 0.278 0.055 -0.215 -0.067 -0.047 0.112 -0.121 -0.108 0.017 0.180 -0.213 0.100 -0.036 0.134 0.017 -0.083 0.089 0.045 -0.321 0.154 -0.176 0.032 0.461 -0.039 -0.055 0.105 -0.175 0.059 -0.057 0.027 -0.172 0.149 Table S1: Standardized Betas yielded from the categorical regressions analyses (bold indicates p < .05). S5 Individual difference in criterion shifting S6 Correlations between variables Table S2: Correlations across the different variables entered in the equation. Bolded values indicate p < .05, uncorrected. Other variables significantly related to criterion shifting, but mostly through shared variance: Sleep had a negative effect on criterion shift (Words Beta: -.235, p < .022), but this effect was largely mediated by correlated variables: procedure variations and rank. Verbal tendencies also consistently positively effected criterion shifting (nearly significant for Faces, Beta: .174, p < .052), although this measure was highly mediated by other characteristics, namely rank. Individual difference in criterion shifting S7 Military Rank and Criterion Shifting Because the regressions included non-military participants entered as 0 for military rank, we also ran a regression with only the military participants and included other military variables besides rank (e.g., time in army, length of deployment, months since last deployment, and combat experience). This regression was run with the procedural, memory, and RCI variables entered first, as in the categorical regressions run in step one. The purpose of this regression was to investigate whether the relation between rank and criterion shift held up with only military participants, and to try to reveal what aspects of military experience was the driving factor in the original relation found between rank and criterion shifting. In these regressions, rank still had a similar effect on criterion shifting, and the strongest effect compared to all other military variables, however it was only significant in the Words dataset (Beta: .349, p < .013) (see Table S3). None of the other military variables were significantly related to criterion shifting. This suggests that there is something inherent about the leadership role and advancement in rank that relates to criterion shifting for Words that is independent from other military experience. For the Faces dataset, rank still had a strong effect (Beta: .228), but was mediated by other factors such as time in army. Table S3: Standardized Beta values yielded from the military regression. N = 68. Bold indicates p < .05.