VHS MUN 2012 - Vivek High School

advertisement

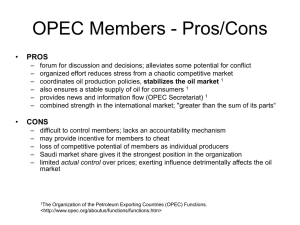

VHS MUN 2012 Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries: (OPEC) Agendas: 1. The Global Energy Scene 2030; 2. The current oil market and development of alternate fuels Letter from the Executive Board Greetings Delegates, Welcome to the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries of VHS MUN 2012 - Our expectations from the committee are very simple and clear, and revolve around an aim of being able to create a situation of an intense and a fruitful debate over the issues to be discussed, which shall in turn serve as an enriching learning experience for each and every member of the committee. The agendas that have been decided upon, bear a dual character of being, plain on the surface of it along with being complex enough to test your research and intellectual competencies. I am sure that this committee would turn out to be a perfect amalgamation of sheer work and substance along with enjoyment and ever lasting memories. Be a part of OPEC, with a motive to contribute in a way to solve the persisting world problems in hand, mainly relating to The Global Energy Scene 2030 which would give each one of us a broad vision to picture and foresee the world in terms of Oil crisis which might take place after a few years and on the contrary would encourage us to plan the development of alternate fuels, keeping in mind the current oil market. We as the Executive Board of this committee would like to wish each one of you all the luck to prepare well, and give your best whilst looking forward to the best MUN'ING experience of your lives. However, we would like to mention that each one of us would appreciate your originality and novelty of ideas and hence would like, if you opt to think out of the box and not refer to the Background Guide, for every issue. And for everything else, please feel free to contact the Executive Board of OPEC, at anytime and under any circumstance. Thanking You Kudrat Dutta Chaudhary Chair Pranav Sahni Director Seerat Brar Rapporteur Organisation of Oil Exporting Countries (OPEC) Overview: The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is a permanent, intergovernmental Organization, created at the Baghdad Conference on September 10–14, 1960, by Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. The five Founding Members were later joined by nine other Members: Qatar (1961); Indonesia (1962) – suspended its membership from January 2009; Libya (1962); United Arab Emirates (1967); Algeria (1969); Nigeria (1971); Ecuador (1973) – suspended its membership from December 1992-October 2007; Angola (2007) and Gabon (1975–1994). OPEC had its headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland, in the first five years of its existence. This was moved to Vienna, Austria, on September 1, 1965. According to the Statutes, OPEC's objective is to co-ordinate and unify petroleum policies among Member Countries, in order to secure fair and stable prices for petroleum producers; an efficient, economic and regular supply of petroleum to consuming nations; and a fair return on capital to those investing in the industry. One of the principal goals is the determination of the best means for safeguarding the organization's interests, individually and collectively. It also pursues ways and means of ensuring the stabilization of prices in international oil markets with a view to eliminating harmful and unnecessary fluctuations; giving due regard at all times to the interests of the producing nations and to the necessity of securing a steady income to the producing countries; an efficient and regular supply of petroleum to consuming nations, and a fair return on their capital to those investing in the petroleum industry. MEMBER COUNTRIES The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was founded in Baghdad, Iraq, with the signing of an agreement in September 1960 by five countries namely Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. They were to become the Founder Members of the Organization. These countries were later joined by Qatar (1961), Indonesia (1962), Libya (1962), the United Arab Emirates (1967), Algeria (1969), Nigeria (1971), Ecuador (1973), Gabon (1975) and Angola (2007). From December 1992 until October 2007, Ecuador suspended its membership. Gabon terminated its membership in 1995. Indonesia suspended its membership effective January 2009. Currently, the Organization has a total of 12 Member Countries. The OPEC Statute distinguishes between the Founder Members and Full Members - those countries whose applications for membership have been accepted by the Conference. The Statute stipulates that “any country with a substantial net export of crude petroleum, which has fundamentally similar interests to those of Member Countries, may become a Full Member of the Organization, if accepted by a majority of three-fourths of Full Members, including the concurring votes of all Founder Members.” The Statute further provides for Associate Members which are those countries that do not qualify for full membership, but are nevertheless admitted under such special conditions as may be prescribed by the Conference. NOTE : Now, according to this the committee OPEC of the VHS MUN’2012 , shall be differentiating between the member countries and the observer countries. The permanent members namely : Algeria, Angola, Ecuador , Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, U.A.E, Venezuela, shall be the ‘only’ countries voting upon the resolution that is deliberated and discussed and collectively decided upon by both the permanent members and observer countries. However, on the other side, the observer nations which are : USA, UK, China, France, Russia, India, Canada, Brazil, Japan, Germany, Egypt, Australia, would be allowed to take part in the normal procedural voting and also would be as much a part of the committee as the permanent members and hence their opinions would be considered in the framing to the Resolution BUT they won’t be allowed to vote, for or against the resolution in order to pass or reject it. We at the MUN shall be following the code and conduct of the actual committee and this rule has been derived from the very same. OPEC STATUTE CHAPTER I Organization and Objectives Article 1 The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), Herein after referred to as “the Organization”, created as a permanent intergovernmental organization in conformity with the Resolutions of the Conference of the Representatives of the Governments of Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela, held in Baghdad from September 10 to 14, 1960, shall carry out its functions in accordance with the provisions set forth hereunder. Article 2 A. The principal aim of the Organization shall be the coordination and unification of the petroleum policies of Member Countries and the determination of the best means for safeguarding their interests, individually and collectively. B. The Organization shall devise ways and means of ensuring the stabilization of prices in international oil markets with a view to eliminating harmful and unnecessary fluctuations. C. Due regard shall be given at all times to the interests of the producing nations and to the necessity of securing a steady income to the producing countries; an efficient, economic and regular supply of petroleum to consuming nations; and a fair return on their capital to those investing in the petroleum industry.2 Article 3 The Organization shall be guided by the principle of the sovereign equality of its Member Countries. Member Countries shall fulfil, in good faith, the obligations assumed by them in accordance with this Statute. Article 4 If, as a result of the application of any decision of the Organization, sanctions are employed, directly or indirectly, by any interested company or companies against one or more Member Countries, no other Member shall accept any offer of a beneficial treatment, whether in the form of an increase in oil exports or in an improvement in prices, which may be made to it by such interested company or companies with the intention of discouraging the application of the decision of the Organization. Article 5 The Organization shall have its Headquarters at the place the Conference decides upon. Article 6 English shall be the official language of the Organization.3 CHAPTER II Membership Article 7 A. Founder Members of the Organization are those countries which were represented at the First Conference, held in Baghdad, and which signed the original agreement of the establishment of the Organization. B. Full Members shall be the Founder Members, as well as those countries whose application for membership has been accepted by the Conference. C. Any other country with a substantial net export of crude petroleum, which has fundamentally similar interests to those of Member Countries, may become a Full Member of the Organization, if accepted by a majority of three-fourths of Full Members, including the concurrent vote of all Founder Members. D. A net petroleum-exporting country, which does not qualify for membership under paragraph C above, may nevertheless be admitted as an Associate Member by the Conference under such special conditions as may be prescribed by the Conference, if accepted by a majority of three-fourths, including the concurrent vote of all Founder Members .No country may be admitted to Associate Membership which does not fundamentally have interests and aims similar to those of Member Countries.4 E. Associate Members may be invited by the Conference to attend any Meeting of a Conference, the Board of Governors or Consultative Meetings and to participate in their deliberations without theright to vote. They are, however, fully entitled to benefit from all general facilities of the Secretariat, including its publications and library, as any Full Member. F. Whenever the words “Members” or “Member Countries” occur in this Statute, they mean a Full Member of the Organization, unless the context demonstrates to the contrary. Article 8 A. No Member of the Organization may withdraw from membership without giving notice of its intention to do so to the Conference. Such notice shall take effect at the beginning of the next calendar year after the date of its receipt by the Conference; subject to the Member having at that time fulfilled all financial obligations arising out of its membership. B. In the event of any country having ceased to be a Member of the Organization, its readmission to membership shall be made accordance with Article 7, paragraph C. THE GLOBAL ENERGY SCENE 2030 KEY ASSUMPTIONS The Reference scenario The Reference scenario aims at providing a description of the future world energy system, as if the on-going technical and economic trends and structural changes were to continue. In this respect, it constitutes the appropriate benchmark for the economic assessment of future energy and climate policy options. The Reference scenario was designed with the following philosophy: - The main drivers in the future development of the world energy system will remain the demography and economic growth (Gross Domestic Product). As the on-going trends for these two sets of variables are differentiated across the main world regions, their continuation results in significant changes in the regional structure of population, GDP energy demand and associated emissions. - Technical change has been a continuous phenomenon through history, although this process may be submitted to slowdowns or accelerations. Thus, any projection of the economic system has to take into account the consequences of the continuous improvement in the technologies’ economic and technical performances. As far as energy technologies are concerned, the hypotheses considered in the Reference indeed take into account technological progress, at least along the lines of past improvements (hypotheses of breakthroughs are considered elsewhere in the technology cases). - The availability of energy resources is clearly a potential constraint for the development of fossil fuel use in the long term, or at least it is a factor that can bring tensions on the international energy markets and drive the energy prices up. Coal resources are known to be overabundant, at least for the next century. But huge uncertainties surround any assessment of the recoverable oil and gas resources at the world and regional level. The Reference scenario uses median estimates for resources that are identified at the regional level, with values that are globally well accepted by the experts, in a "business as usual "perspective. - As far as energy and climate policies are concerned, the Reference scenario only includes the consequences of policy measures, which are actually (2000) embodied in "hard decisions" (investment actually made, regulation actually enforced in law and voluntary agreement actually signed). It is even considered by judgement that some measures may not benefit of a full implementation over the projection period. Thus the Reference does not include the compliance to the policy decisions or announcements made by governments, including the European Commission, or industries, such as the Kyoto commitments, the targeted share of renewable, the nuclear phase-out in Germany or Belgium, or the removal of existing economic instruments (eg: subsidies or taxes). This is logical as the cost of these policies, which are being implemented or will be implemented in the near future, can only be assessed by comparison with a reference scenario that is free of such constraints or commitments. As any model, POLES, the model used in this study, is a simplified representation of reality, mostly based on the fundamental economic relations involved in the world energy system .Some important factors, which may have a decisive impact on the future development of the world energy system, are either ignored or at least not explicitly dealt with in the model, because too complex or impossible to quantify. Among these factors: the geopolitical drivers and constraints that have already played a major role on the energy scene, such as the industries’ regulation and organisation schemes, which have changed significantly in the past twenty years. As a consequence, the “business and technical change as usual” energy evolutions depicted by the Reference are mostly driven by changes in economic fundamentals that reflect rational economic behaviours. How these evolutions would modify the geopolitical constraints or foster complementary changes in the industries’ regulation and organisation schemes, and, therefore, which policy response they may induce, is out of the scope of the Reference generated by POLES. PRIMARY FUEL SUPPLY Simulation of Oil and Gas Discovery World Oil Supply The Simulation of Oil and Gas Reserves – More Information World Conventional Oil Resources Opec and Non- Opec Conventional Oil Resources World Oil Production Here are certain conclusions that need to be considered while analysing the futuristic issue in hand : The Current Oil Market and development of Alternate Fuels ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS AND OPEC OPEC supports sound environmental policies that are fair and equitable, based on proven needs and designed to address those needs. OPEC is concerned about the environment and we want to ensure that it is clean and healthy for future generations. OPEC also supports sustainable economic development, which requires steady supplies of energy at reasonable prices. Many countries have already introduced heavy taxes on oil products. In some countries, the price that motorists pay for gasoline is three or four times higher than the price of the original crude oil. Taxes account for up to 70 per cent of the final price of oil products in some countries. As a result of these taxes, some of the oil-consuming countries (especially those in Europe where taxation levels are highest) receive much more income from oil than OPEC does. OPEC is concerned that many of the socalled 'green' taxes that are currently levied on oil do not specifically help the environment. Instead, they simply go into government budgets to be spent on other things. Taxes might lead to instability in the oil industry, creating problems for many countries and industries. Industrialised countries are developing policies to limit the use of fossil fuels in order to reduce their emissions of carbon dioxide. Many are already levying heavy taxes, particularly on oil products. Yet studies have shown that OECD members could cut their carbon dioxide emissions by 12 per cent by 2010 and still maintain their tax revenues, if they adopted a pro rata tax system that levies tax on all forms of energy according to their carbon content. OPEC is concerned that some countries may impose environmental and taxation policies that are harmful to those who rely on fossil fuels for a substantial part of their income. Some countries with high oil taxes actually subsidise domestic coal production, yet coal produces more carbon dioxide than oil. Carbon dioxide is one of the greenhouse gases which are believed to contribute to global warming. OPEC is worried about discriminatory oil taxes because we are committed to providing a stable petroleum market. The OPEC feels that there is a need to invest in oil exploration and development in order to have production capacity available as demand rises in the years ahead, but we also need to be sure that there will be enough demand for that oil and that we will get a reasonable price. If there is no investment in expanding oil production capacity before it is needed, the world could face sudden price shocks, leading to serious global economic problems. OPEC is also concerned that many of the environmental policies now being proposed and adopted do not have the full support of the scientific community. There is still considerable debate about the impact of global warming, and how it can best be addressed. OPEC supports further research into these important issues. OPEC is also spending heavily to improve its environmental impact, by locating sources of higher quality oil and gas, by developing cleaner fuels for consumers, and by reducing the impact of its activities through safer, cleaner drilling, transportation and refining processes. OPEC also participates in many international meetings in order to remind governments and others who are debating environmental policies that they must consider the needs of developing countries, especially those that rely on their income from oil TOP OIL PRODUCING NATIONS Source : CIA World Factbook ALTERNATIVE SOURCES TO OIL High oil prices, growing concerns over energy security, and the threat of climate change have all stimulated investment in the development of alternatives to conventional oil. Substitutes for existing petroleum liquids (ethanol,biodiesel, biobutanol, dimethyl ether, coal-to-liquids, tar sands, oil shale),are both from biomass and fossil feedstocks. The technology pathways to these alternatives vary widely, from distillation and gasification to bioreactors of algae and high-tech manufacturing of photonabsorbing silicon panels. Many are considered “green” or “clean,” although some, such as coal-to-liquids and tar sands, are “dirtier” than the petroleum they are replacing. Others, such as biofuels, have concomitant environmental impacts that offset potential carbon savings. Unlike conventional fossil fuels, where nature provided energy over millions of years to convert biomass into energydense solids, liquids, and gases—requiring only extraction and transportation technology for us to mobilize them—alternative energy depends heavily on specially engineered equipment and infrastructure for capture or conversion, essentially making it a high-tech manufacturing process. However, the full supply chain for alternative energy, from raw materials to manufacturing, is still very dependent on fossil-fuel energy for mining, transport, and materials production. Alternative energy faces the challenge of how to supplant a fossil-fuel-based supply chain with one driven by alternative energy forms themselves in order to break their reliance on a fossil-fuel foundation. The public discussion about alternative energy is often reduced to an assessment of its monetary costs versus those of traditional fossil fuels, often in comparison to their carbon footprints. This kind of reductionism to a simple monetary metric obscures the complex issues surrounding the potential viability, scalability, feasibility, and suitability of pursuing specific alternative technology paths. Although money is necessary to develop alternative energy, money is simply a token for mobilizing a range of resources used to produce energy. At the level of physical requirements, assessing the potential for alternative energy development becomes much more complex since it involves issues of end-use energy requirements, resource-use trade-offs (including water and land), and material scarcity. Similarly, it is often assumed that alternative energy will seamlessly substitute for the oil, gas, or coal it is designed to supplant—but this is rarely the case. Integration of alternatives into our current energy system will require enormous investment in both new equipment and new infrastructure—along with the resource consumption required for their manufacture— at a time when capital to make such investments has become harder to secure. This raises the question of the suitability of moving toward an alternative energy future with an assumption that the structure of our current large-scale, centralized energy system should be maintained. Since alternative energy resources vary greatly by location, it may be necessary to consider different forms of energy for different localities. DEMAND OF OIL – PAST PRESENT AND FUTURE OPEC believes that oil demand will continue to grow strongly and oil will remain the world's single most important source of energy for the foreseeable future. The OWEM reference case sees oil's share of the world fuel mix falling slightly from over 41 per cent today to just over 39 per cent in 2020. However, oil will still be the world's single largest source of energy. The reduction in oil's market share is largely due to the stronger growth enjoyed by other forms of energy, particularly natural gas In June 2012, OPEC closed one of their sessions with an assessment of the long-term oil outlook, which underlined that oil will remain the leading fuel type in satisfying the world's growing energy needs for the foreseeable future and that resources are clearly sufficient. Moreover, OPEC is investing in accordance with perceived demand for its crude. Nevertheless, great uncertainties remain, including the path of the global economic recovery; policy announcements that offer confusing signals to investors; industry costs; technology; and human resources. OPEC underscored the final conclusions of a study on technological advances in the road transportation sector. The study covers conventional technologies, alternative technologies and fuels, possible bottlenecks, potential drivers (such as legislative requirements and consumer preferences) and expectations for alternatives penetrating both the light and heavy duty vehicle markets. The report also looked at how the impacts of these technology advances could translate into changes in oil demand, as well as the potential differences between the big economic blocks/regions. OPEC believes that oil demand will continue to grow strongly and oil will remain the world's single most important source of energy for the foreseeable future. OPEC’s World Oil Outlook reference case sees oil’s share of the world’s primary energy mix falling slightly from 34.5 per cent in 2010 to just over 32 per cent in 2020 and to 28.4 per cent in 2035. However, oil will still be the world's single largest source of energy. The reduction in oil's market share is largely due to the stronger growth enjoyed by other forms of energy, particularly coal and natural gas. Oil is a limited resource, so it may eventually run out (although not for many years to come). At the rate of production in 2010, OPEC's oil reserves are sufficient to last for more than 113 years, while non-OPEC oil producers’ reserves might last less than 18 years. The worldwide demand for oil is rising and OPEC is expected to be an increasingly important source of that oil. If we manage our resources well, use oil efficiently and develop new fields, then our oil reserves should last for generations to come. Source : WOO 2011 OPEC LONG TERM STRATEGY: The OPEC Ministerial Conference adopted a comprehensive new Long- Term Strategy (LTS) in Vienna on 14 October 2010. This coincided with the celebration of OPEC’s 50th Anniversary. The LTS, which has been prepared over the past year, incorporates extensive research and analysis, and provides a clear and consistent framework for the Organization’s future. It defines three overall objectives, identifies the key challenges that the Organization faces now and in the future, explores a number of scenarios that depict plausible, consistent and contrasting futures of the energy scene, and formulates the elements of strategy to successfully attain its objectives and adequately address the identified challenges. The projections show that future demand levels are well below what was expected at the time of the previous LTS (released in 2005), a consequence of the impacts of the global economic recession and the introduction of new policies that have reduced expectations for oil demand growth. However, growing supply needs in emerging markets will continue to fuel development, especially as the axis of the global economy increasingly shifts towards developing Asia. World oil demand in the three scenarios The substantial decline in crude oil demand — as a result of the global economic downturn, coupled with the wave of new refining capacity that has come on stream in the past few years — has significantly impacted refining sector fundamentals. In the medium-term, low utilization rates and depressed profitability are likely, especially in the Atlantic basin. Consequently, there is in- creasing potential for refinery closures in the US, Europe and Japan. In the longer term, the proportion of crude oil that needs to be refined per barrel of incremental product declines further as the percentage share of biofuels, gasto-liquids, coal-to-liquids, NGLs and other non- crudes in total supply continues to rise. Combined with projected developments on the demand side, this will limit future requirements for additional distillation capacity. From a regional perspective, new capacity — driven by a further shift towards middle distillates and light products — will be needed primarily in the AsiaPacific and Middle East regions. This underscores the emerging contrast between the Atlantic and Asia-Pacific basins. The former of these, dominated by Europe and the US, is the centre of the refining surplus. Conversely, the Asia-Pacific basin is the hub of capacity growth. Therefore, the prospect is for a substantial reshaping of the oil downstream and a regional shift toward Asia. OPEC National Oil Companies should further enhance technology- based cooperation among themselves, as well as with other international institutions. For example, research and development collaboration among Member Countries should be encouraged to rapidly develop a portfolio of projects in such areas as oil-use efficiency, as well as in advancing research into the production of cleaner crude oil-based transportation fuels. In climate change-related multilateral for a, OPEC Member Countries will continue to play an active role. In this regard it is essential that the international community ensures the full and sustained implementation of the principles and provisions included in the United Nations (UN) Framework Convention on Climate Change, such as the principles of ‘equity’ and ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’. Equally important is its ongoing commitment to minimize the ad- verse impacts of policies and measures on developing countries, whose economies are heavily dependent on the production and export of fossil fuels; the use of flexible mechanisms and sinks such as forests; the provision of additional, sustained and adequate financial resources for adaptation; and the transfer of technology. The active engagement of OPEC in global trade negotiations is also important. In this respect, it is crucial to constantly adhere to the principle of the permanent sovereignty of nations over their natural resources, and the use of the comparative advantage provided by this resource. Non OECD Demand: China’s oil demand experienced its weakest quarterly growth in the third quarter of 2011 since the first quarter of 2009. Many factors led to this weak performance, such as the slowdown in economic activity, high retail prices and the government’s energy-savings programme. However, the fourth quarter’s oilusage rose by 5.5 per cent, so that the year ended with 5.1 per cent growth. Despite the substantial weakening in the months after the summer and the expiry of sales incentives in the form of tax-breaks for small-engined vehicles, Chinese auto sales rose, adding 18 million units, or 2.5 per cent, during the year. As one would expect, the Japanese earthquake had a negative effect on the auto industry in China (and the USA). Indian oil consumption in the transportation (which had a boom in new car registrations) and industrial sectors displayed solid growth during the year, but was offset slightly by fuel substitution to gas in the petrochemical and power plant industries. Furthermore, shortages in electricity supply led to a push for independent diesel-operated generators, and this resulted in more diesel consumption during the year. As a result of India’s oil demand, ‘Other Asia’s’ oil demand grew by 0.3 mb/d for the year. The Indian auto market experienced negative growth in December. But, for the whole of 2011, Indians bought three million more cars, due to the government’s new car sales incentives. Energy-intensive projects in the Middle East, especially Saudi Arabia, saw a hike in the region’s oil demand of 2.4 per cent in 2011. The region’s demand has been growing steadily in the past few years. The product that was consumed the most in 2011 was diesel, which was used by both the transport and industrial sectors. Due to the weak- ness in Iranian demand, growth in the region’s consumption lagged behind that of Latin America. The non-OECD region’s demand accounted for all the global demand growth in 2011, totaling 1.2 mb/d y-o-y. The strongest growth was seen in China, followed by Other Asia, Latin America and, finally, the Middle East. Shale Oil: Following on from what have some have termed the ‘US shale gas revolution’, which is also now having some impact globally, questions are being asked as to whether shale oil will have a similar effect, particularly in the US. Shale deposits rich in organic matter and movable oil are very common and exist in almost all known oil fields, but to date there has been very little exploitation of this resource. Is this about to change? It is important to stress that there has been much interchangeable use of the terms ‘shale oil’, ‘oil shale’ and kerogen. The focus of this box is on the production of crude oil from shale deposits, not the conversion of kerogen from shale into crude oil. Here, the term ‘shale oil’ (sometimes described as ‘tight oil’) will be used to refer to crude oil produced by the hydraulic fracturing of shale. Despite widespread shale deposits, it is not yet clear whether the availability of economically viable shale oil is as great as that for shale gas. It is already evident that some deposits will not be sufficiently mature to contain liquids, and some will be over-mature. The geographical, geological and operational challenges and associated costs across countries and regions will be diverse. Nevertheless, given the size of known shale oil deposits, even if only a fraction of them contain viable liquids, it translates into a significant resource. Known shale oil resources cover several basins in the US (Bakken, Eagle Ford, Niobrara, Utica, Leonard Avalon, Woodford and Monterey), but also in other parts of the world (Beetaloo in Australia, Exshaw and Macasty in Canada, Paris in France and Vaca Muerta in Argentina). Due to the lack of data, estimates of oil in place and recoverable volumes from these formations are still the subject of huge uncertainties. To date, only the Bakken oil shale formation in North Dakota and Eagle Ford in Texas have been exploited for a sufficient period of time to have a clear understanding of actual resources and reserves. A number of other deposits are being targeted, but given that many are in their infancy, data on the resources in place and the estimated recoverable reserves is generally limited, and beset with uncertainties. As a result, a wide variety of claims – both conservative and optimistic – have been made, but so far it remains difficult to ascertain the longterm prospects for shale oil. At the global level, a very conservative estimate of global shale oil ‘proved’ reserves, based on a 3% recovery factor, is less than 100 billion barrels. In this case, shale oil will only add incremental amounts to the medium-term global oil supply. A more optimistic estimate of global shale oil ‘proved’ reserves, again with a 3% recovery factor, is projected to be more than 300 billion barrels. In this case, shale oil might prove to be a significant long-term contributor to global oil supply. In terms of development and production, what makes shale oil unusual is that it does not involve a new technology or a newly-discovered resource. The hydraulic fracturing technology has been used for many years – especially in the US – and the resource, although not exploited, exists in most known fields. As in the case of shale gas, this can be expected to speed-up the rate at which exploitation occurs and implies that the time it will take to spread will be faster than if these were completely new fields. On the other hand, supply is very dependent on the drilling effort and, thus, is more price elastic. Significant constraints over the next ten years include: the need for geological analysis of other shales; trained people to perform hydraulic fracturing; and acquiring the horizontal drilling and fracturing equipment. In the US already, costs have accelerated sharply as the demand for fracing equipment cannot be met. Thus, delays in initiating fracturing jobs are common. In some areas, such as northern Europe, environmentally-driven political opposition can also be expected to slow or possibly prevent development. Outside of the US and Canada, there are at present only three basins that have been analyzed sufficiently to be viewed as having potential for near-term production. These are the Vaca Muerta in Argentina, the Beetaloo in Australia, and the Paris basin in France. The last, however, faces strong political opposition and develop- ment will likely be delayed for years. Elsewhere, China is moving aggressively to study and exploit its shale oil resources and production there is likely to start growing following a few years of evaluation and human resource training. And if other countries such as Brazil, as well as those with shale oil deposits in North Africa, encourage operations, then after around five years, perhaps small increments may also be observed from these areas. Regions such as central Africa and Siberia will not be developed soon, because of their lack of infrastructure, and regions such as the Middle East have no need at present to develop a higher-cost, unconventional resource. Development costs for shale oil appear to be roughly in the $30–$80/b range, excluding taxes and royalties. However, as the industry develops and moves further along the learning curve, costs can be expected to come down, perhaps sharply over the medium-term, before flattening out. Depletion will not be a significant factor, due to the size of the resource, but in the short-term, pressure on the limited amount of crews and equipment could drive costs up. Looking ahead, it is evident that output from new shale oil deposits will not grow at a similar rate of 60,000 b/d per year as the Bakken basin is presently, but capacity will expand for years to come as more and more rigs and fracing equipment are brought in. Within a decade, it is quite possible that shale oil production could rise at relatively significant levels year-on-year, assuming prices remain well above $60/b, and regions such as Argentina, Australia and Canada do not significantly restrict operations. At present, however, shale oil should not be viewed as anything more than a source of marginal additions. Biofuels: The pattern of biofuels supply follows three distinct phases. Over the mediumterm, there is an initial supply surge, with first generation technologies used to supply the vast bulk of this. In the medium-term, biofuels rise from 1.8 mb/d in 2010, to 2.7 mb/d in 2015 (Table 3.6). This increase is focused mainly on the US, Europe and Brazil. Increasingly, however, in the second of these phases, sustainability issues place a limitation on how much first generation biofuels can be produced. Indeed, recently, some countries have revised their policy push in favour of biofuels by relaxing their blending mandates, for example, in Germany, or by developing sustain- ability criteria, as seen in the EU as a whole. Higher sugar prices have also led to a downward revision of ethanol mandated blending in Brazil. Moreover, the economic crisis and the resulting pursuit of fiscal consolidation in many countries will likely make it more difficult to justify and sustain expensive support programmes that favour biofuels. This means that, after the medium-term period, the Reference Case sees a slowdown in the rate of increase. This will be particularly apparent in the US and Europe, which in turn may mean that some ambitious targets may not be met. In the longer term, the third phase, it is assumed that second generation technologies – and third generation biofuels technology, such as algae-based fuels – be- come increasingly economic, leading to a resurgence in biofuels supply growth. The Reference Case sees biofuels supply rising by more than 5 mb/d from 2010, to reach 7.1 mb/d by 2035 (Table 3.7). The growing importance of second and third generation biofuels over the longer term introduces considerable uncertainty to the outlook. Increases could feasibly be considerably higher, once these technologies become a commercial reality and should costs decline substantially. The development of these technologies is also likely to be sensitive to how oil prices evolve. The considerable uncertainty in the biofuel outlook will be addressed through continuous monitoring of its main drivers; mainly government mandates and policies that provide the required incentives to increase biofuel production. These mandates, although varying considerably from country-to-country, will continue to be the most important factor in the biofuel equation. So far, and regardless of all the fiscal challenges (increased feedstock costs, the food versus fuel debate and the argument that biofuels are not as environmentally-friendly as was previously believed), new man- dates continue to be introduced in support of biofuel programmes. For example, in the US, the reinstatement of the biodiesel blender tax credit at the end of 2010 is the main reason behind its production increase in 2011. OPEC upstream investment activity In 2010, OPEC’s spare capacity stood at more than 5 mb/d. While this capacity fell to about 4 mb/d during the second and third quarter of 2011 as a result of the disruption in Libya’s production, it is expected to stabilize at about 8 mb/d over the medium- term. Given the industry’s long-lead times and high upfront costs, it is indeed an extremely challenging task to strike the right balance for investment in new capacity. The ever-evolving dynamics of supply and demand, as well as other market uncertain- ties, adds further to the budgeting and planning complexity. Of utmost importance, in respect to investments, is a stable and realistic oil price; one that is high enough for producers to continue to invest and develop resources and low enough to not hinder global economic growth. It is important not to forget the renewed sense of caution that the financial crisis of 2008 planted in investors’ minds. The oil and gas industry, which has typically been slow to increase investment when the oil price goes higher, will likely continue to respond faster to low oil prices. Nonetheless, this does not mean that costs will respond in the same way, as even during the financial crisis the high cost environment persisted. Costs did fall a little towards the end of 2009, but they are now back to the same high levels of 2008. Regardless of all the challenges and uncertainties, OPEC Member Countries continue to invest in additional capacities. On top of the huge capacity maintenance costs that Member Countries are faced with, they continue to invest in new projects and reinforce their commitment to the oil and gas market and as well as to the security of supply for all consumers. Needless to say, this is only a reflection of OPEC’s well- known policy that is clearly stated in its Long-Term Strategy and its Statute. Based on the latest upstream project list provided by Member Countries, the OPEC Secretariat’s database comprises 132 projects for the five-year period 2011– 2015. This could translate into an investment figure of close to $300 billion should all projects be realized. This shows how large OPEC’s project portfolio is. Investment decisions are influenced by many factors, such as the price of oil and the perceived need for OPEC oil. Under the Reference Case conditions, and taking into account all OPEC liquids, including crude, NGLs and GTLs, as well as the natural decline in producing fields and current circumstances, the net increase in OPEC’s liquids capacity by 2015 is estimated to be close to 7 mb/d above 2011 levels, with more thereafter, leading to comfortable levels of spare capacity. SUPPLY OF OIL OPEC has a policy of maintaining stability in the oil market, and its Member Countries have often done this by increasing or decreasing the amount of oil they produce. Only OPEC nations have a significant spare oil production capacity, and this enables them to increase production at relatively short notice. However, because OPEC is not the only source of oil in the market, it cannot guarantee the movement of oil prices, or the availability of supplies to all consumers at all times. OPEC has around 81 per cent of the world's oil reserves, and this will enable us to expand oil production to meet the growth in demand. But in order to expand our output, we need to be sure that the oil industry will continue to be profitable. Oil producers invest billions of dollars in exploration and infrastructure (drilling and pumping, pipelines, docks, storage, refining, staff housing, etc) and a new oil field can take 3-10 years to locate and develop. If oil producers do not invest enough money and do it far enough in advance, then the world could face a shortage of oil supplies in future. Therefore, OPEC is concerned about issues that undermine the prosperity of the oil industry and thus threaten the security of world oil supplies. One such issue is oil taxation in the consuming countries. Although OPEC does try to maintain stability and invest in a timely manner, our efforts to guarantee the security of oil supplies can be undermined - or supported - by the actions of oil consumers. Yes, oil consumers need steady supplies of oil, and oil producers rely on steady demand. If demand changed suddenly it would have a major impact on the profitability of oil producers and the economies of many countries around the world. Oil production is a long-term affair: the oil industry works 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, excluding maintenance or bad weather and other disruptions. Oil facilities require many millions of dollars of investment, and the investors try to earn a reasonable return on their capital. A downturn in oil demand could force oil production to slow down or stop. This could physically damage the oil fields, reducing the amount of oil that can be recovered in future. The oil installations could also be damaged. Some facilities, such as those operating in the oceans, are very difficult and expensive to shut down. When production slows down, oil producers might be forced to lay off staff. Downstream operators, such as gasoline retailers, refiners and transport companies, could also be forced to shed staff. If oil producers receive lower incomes they must spend less money and import fewer goods from oil consumers. If investors are unsure about the risks and the likely returns from petroleum investments they may not make those investments. If we do not invest enough money, or do it far enough in advance, then the world could face a shortage of oil supplies and a downward spiral in the global economy. However, if oil producers continue to receive reasonable prices and stable demand, they will maintain their production and invest far enough in advance to meet the growth of demand. Thus the security of oil supplies relies upon the security of oil demand. Oil producers - and oil consumers - need to work together to ensure that the security of oil supply and demand is preserved. OIL TAXES Oil taxes reduce the incomes of oil producers, and limit the funds they have available for maintenance, exploration and production activities. Oil taxes also limit the growth in oil demand and raise costs for other industries. As a result, oil producers and other investors are unsure of the future development of oil prices and profits, and they might hesitate from making the necessary investments This graph illustrates the inter-country variations in the price of one litre of oil across the G7 countries during 2010. The price variations, however, are not due to differences in crude oil prices but rather to the widely varying levels of oil taxes (shown in red) in those major oil consuming nations. These can range from relatively modest levels - in the USA and Canada - to very high levels in Europe. In the UK, for example, the government earned US $1.15 (or around 65%) from the US $1.78 retail price of a litre of pump fuel in 2010, while oil producing countries (including OPEC) earned only US $0.51 (or around 29%) of this total pump fuel price. EVALUATION OF OIL PRICES- THE MECHANISM OPEC does not control the oil market. OPEC Member Countries produce about 42 per cent of the world's crude oil and 18 per cent of its natural gas. However, OPEC's crude oil exports represent about 60 per cent of the crude oil traded internationally. Therefore, OPEC can have a strong influence on the oil market, especially if it decides to reduce or increase its level of production. OPEC seeks stability in the oil market and endeavours to deliver steady supplies of oil to consumers at fair and reasonable prices. The Organization has achieved this in a number of ways: sometimes by voluntarily producing less oil, sometimes by producing more when there is a shortfall in supplies (such as during the Gulf Crisis in 1990, when several million barrels of oil per day were suddenly removed from the market). One of the most common misconceptions about OPEC is that the Organization is responsible for setting crude oil prices. Although OPEC did in fact set crude oil prices from the early 1970s to the mid-1980s, this is no longer the case. It is true that OPEC's Member Countries do voluntary restrain their crude oil production in order to stabilize the oil market and avoid harmful and unnecessary price fluctuations, but this is not the same thing as setting prices. In today's complex global markets, the price of crude oil is set by movements on the three major international petroleum exchanges, all of which have their own Web sites featuring information about oil prices. They are the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX, http://www.nymex.com), the International Petroleum Exchange in London (IPE, http://www.ipe.uk.com) and the Singapore International Monetary Exchange (SIMEX, http://www.simex.com.sg). The Web sites of the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA, http://www.iea.org) and the US Energy Information Administration (EIA, http://www.eia.doe.gov), also have extensive historical information on oil prices. The Oil and Energy Ministers of the OPEC Member Countries meet at least twice a year to co-ordinate their oil production policies in light of the market fundamentals, ie, the likely future balance between supply and demand. The Member Countries, represented by their respective Heads of Delegation, may or may not alter production levels during the Meetings of the OPEC Conference. Given that OPEC Countries produce about 42 per cent of the world's crude oil and about 60 per cent of the crude oil traded internationally, any decisions to increase or reduce production may lower or raise the price of crude oil. The impact of OPEC output decisions on crude oil prices should be considered separately from the issue of changes in the final prices of oil products, such as gasoline or heating oil. There are many factors that influence the prices paid by end consumers for oil products. In some countries taxes comprise over 60 per cent of the final gasoline price paid by consumers, so even a major change in the price of crude oil might have only a minor impact on consumer prices. Alternate Energy Sources: Nuclear Energy: As countries seek to find the right balance in the energy trilemma we have seen that many governments have reviewed their plans for the utilisation of nuclear in the energy mix. A perspectives report by the World Energy Council titled “Nuclear Energy One Year After Fukushima” shows that 50 countries are still building, operating or and that 60 reactors are currently under construction, 20 in China alone, with the majority being in emerging countries. This can mean two things : a) Climate change is considered as a real threat and that countries envisage nuclear energy as an efficient means to contributing and curbing climate change. b) These nations believe in the concept of nuclear energy and are willing to strengthen nuclear safety through reinvigorated international governance. Coal: The Global Coal industry has experienced an incredible decade, with demand growth for this one fuel alone nearly matching the aggregate growth seen across gas, oil, nuclear and all forms of renewable energy sources.The importance of coal in the global energy mix is now the highest since 1971. It remains the backbone of electricity generation and has been the fuel underpinning the rapid industrialisation of emerging economies, helping to lift hundreds of millions of people out of energy poverty.Maintaining current policies would see coal use rise by a further 65 per cent by 2035, overtaking oil as the largest fuel in the global energy mix. So it is clear that energy and environmental policy will play a decisive role in future coal use. In some countries, its use may be deliberately encouraged for economic, social or energy security reasons. For instance, if action were taken to provide electricity access by 2030 to the 1.3 billion people in the world without it today, coal would be expected to account for more than half of the fuel required to provide additional on-grid connections. In other countries, policies may be designed to encourage switching away from coal to more environmentally benign or lower carbon sources, such as through air quality regulations or carbon penalties. While a global agreement on carbon pricing has been elusive, a growing number of countries are taking steps to put a price on carbon emissions. In the longer term, the deployment of carbon capture is another potential “game-changer” for coal. If widely deployed, CCS technology could potentially reconcile the continued widespread use of coal with the need to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. While the technology exists to capture, transport and permanently store these emissions in geological formations, it has yet to be demonstrated on a large scale in the power and industrial sectors and so costs remain uncertain. The current picture is still one in which many legal, regulatory and economic issues need to be resolved. The experience yet to be gained from the operation hence, the prospects for widespread deployment of CCS. In the longer term, the deployment of carbon capture and storage technology is another potential “game-changer” for coal. If widely deployed, CCS technology could potentially reconcile the continued widespread use of coal with the need to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. While the technology exists to capture, transport and permanently store these emissions in geological formations, it has yet to be demonstrated on a large scale in the power and industrial sectors and so costs remain uncertain. The current picture is still one in which many legal, regulatory and economic issues need to be resolved. The experience yet to be gained from the operation hence, the prospects for widespread deployment of CCS. Taken together the widspread adoption of coal power plants and of CCS would help secure the position of coal in our future energy mix and make an important contribution to tackling climate change. But without these technologies, the world will need to move gradually away from coal towards low-carbon technologies, seeing global coal demand and coal’s share of the energy mix decline in the process. Energy situation by continent: Africa In Africa, energy poverty is more prominent than in any other regions due to the high level of social poverty and the low access to modern energy. About 70 per cent of Sub-Saharan Africa’s (SSA) population (and 58 per cent of Africa’s population) lack access to electricity, while some 80 per cent of SSA’s population without access to electricity live in rural areas. Among all the regions Africa shows the highest interest in the energy-water nexus. There is an expressed concern that if dry cooling is not implemented at power plants, then there will not be enough water to sustain the current population plus cooling for the region’s power plant. Conversely, large-scale hydro is seen as an important asset for Africa and holds great potential for development, but its further development and exploitation requires huge amount of investment, suitable social and environmental framework, political stability and bold economic reforms. It could take time to address all these challenges and to make development happen in a sustainable way. Solar is also viewed with great interest as the prices of photovoltaics continue to fall. Asia Asian countries, especially emerging economies, have experienced increasing demand for electricity as a result of rapid economic growth. To meet the increasing demand, Asian economies are relying heavily upon coal and nuclear as their main energy sources. Understandably, the impact of the events in Japan following the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, while having affected the world, are probably more directly felt in Asia. The fact that Japan has seen the equivalent of a 72 per cent decrease in nuclear power generation, taking into account installed nuclear capacity, has led to other issues. To replace this supply, Japan has estimated US$6bn on increased additional gas imports in 2011. LNG imports to Japan were up 28.2 per cent year on year in January 2012 and, according to the Institute of Energy Economics of Japan and the Japanese Ministry of Finance, Japanese LNG imports in 2011 were 12 per cent higher than in 2010. This understandably brings the issue of energy security to the front for Asia. Europe In Europe, climate framework is clearly an important issue, but it has also become clear that Europe is globally in a other regions to follow a similar climate agenda. Weaker economic activity has led to dramatically lower greenhouse gas emissions, driving down carbon prices for emissions trading, and our survey suggests that carbon prices will continue to decrease. Indeed, new EU data suggests that emissions fell 2.6 per cent last year, prompting carbon prices to fall to a record low of just over €6 a tonne, in line with our analysis. Energy infrastructure, including regional interconnection, is an important agenda for Europe. However, progress in areas such as large-scale, high-voltage transmission projects have been delayed by a lack of regulatory coherence. Transmission bottleneck issues could become more serious in future. The lack of an effective carbon market and a stagnating economy raise uncertainty regarding the future of technologies. In order to reach higher shares of green electricity there is a need for proper integration of renewables. So this strong need for new infrastructure is up against an economic situation that is currently a stress to investment. Latin America and the Caribbean Transforming energy wealth into social development and reducing energy poverty is key to the region. Energy subsidies for demand side in particular are important for developing countries as they are seen to help guarantee access of energy for low-income people. Energy price concerns grow bigger as they could slow down economic development, since we expect energy demand to increase on the other. This region is the only region that has little doubt about the future of biofuels. North America Energy issues are becoming extremely challenged in the North American region. We see that nuclear is both a source of high uncertainty and high impact. With 104 reactors operating in the United States, accounting for 20 per cent of America’s electricity output, and two new reactors having been given Middle East dynamics are an important issue to the North American region as we now see coming to the fore with the impact of oil price on the United States’ political landscape. Unconventional's are critical to the agenda in terms of their abundance and impact on energy prices. Shale gas, oil sands, fracking and tight oil have transformed North America’s energy outlook. Shale gas plays an important role in the global energy market as its global production will increase to 30 per cent by 2030, and 70 per cent of this will come from the US and Canada. As for oil sands, their environmental acceptability, including pipeline construction, will be the key element for their timely development and even the creation of a new market. However, without agreement the Canadian government will look to new, emerging markets such as China. With the anticipated penetration of photovoltaic and wind energy into the grid and the much anticipated advent of the smart grid, the impact of electric storage may grow even bigger for the region. QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER Is the current development of alternative sources of energy affecting economies of OPEC countries? What can the OPEC do to maintain a steady oil market to sustain their economies? Will the demand for oil increase or decrease in the future? If demand decreases due to various factors, what can be the possible solutions to the scenario? Are current prices of oil affecting demand? Will they affect demand in the future? Should OPEC countries solely rely on oil to sustain their economies? Should they diversify to new and alternative sources of energy? IMPORTANT RESEARCH LINKS 1. http://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/pub lications/OPECLTS.pdf 2. http://www.postcarbon.org/Reader/PCReader-Fridley-Alternatives.pdf 3. http://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/pub lications/AR_2011.pdf 4. http://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/pub lications/WOO_2011.pdf 5. http://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/pub lications/Solemn_Declaration_I-III.pdf 6. http://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/pub lications/MOMR_June_2012.pdf 7. http://europeecologie.eu/IMG/pdf/shale-gas-pe-464-425-final.pdf