DOC - Child and Adolescent Development Lab

advertisement

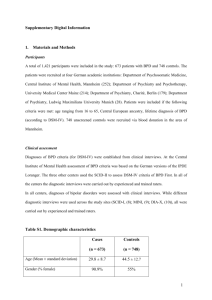

Mothers with Borderline Personality Disorder and their Young Children: Caregiving, Fearful/disoriented Behavior and Role Reversal Jenny Macfie, Chris D. Watkins, Jennifer M. Strimpfel, Christina G. Mena & Amineh Abbas Poster presented at the April 2013 biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Seattle WA Abstract This study assessed how maternal borderline personality disorder (BPD) affects the mother-child interaction in early childhood. A low-SES sample of offspring of women with BPD age 4-7, n = 36, was compared with a normative comparison group, n = 34. We filmed mothers and children solving puzzles and then reliably coded the video tapes. Compared with normative comparisons, and controlling for mood disorders, mothers with BPD were significantly lower on a maternal caregiving composite (sensitivity, autonomy support, hostility reverse-scored), and demonstrated more fearful/disoriented behavior and more role reversal with their children. In addition, self-reported maternal borderline features (affective instability, identity disturbance and negative relationships) were negatively correlated with the maternal caregiving composite and positively correlated with role reversal. Furthermore, maternal identity disturbance was positively correlated with maternal fearful/disoriented behavior, and self-harm was marginally significantly correlated with maternal fearful/disoriented behavior. Introduction Individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) report more intense and frequent emotional pain than do individuals with other personality disorders: anger, fear, and shame (Zanarini et al., 1998). How then might BPD affect a mother’s relationship with her child? This is an important question because the prevalence for BPD is 5.9% in the general population (Grant et al., 2008), and it affects women almost exclusively during their child-bearing years. We know that mothers with BPD are more insensitively intrusive with their infants at 2 and 13 months and that these infants are mostly disorganized in their attachment at 13 months (Crandell, Patrick, & Hobson, 2003; Hobson, Patrick, Crandell, Garcia-Perez, & Lee, 2005). However, there is no research on mother-child interactions for mothers who have BPD beyond infancy. This is a serious omission because of the importance of the development of a goal-corrected partnership between mother and child during early childhood (Bowlby, 1969/1982): maternal BPD may make such a partnership challenging, with serious implications for the negotiation of future stage salient issues such as the development of self-regulation, peer relationships and school functioning (Macfie, 2009). We assessed BPD both as a categorical diagnosis and also along a continuum of self-reported borderline features. Controlling for maternal mood disorders, we hypothesized that in interacting with their young children, (1) mothers with BPD would be lower on an adaptive caregiving composite, higher on fearful/disoriented behavior and higher on role reversal with their children, than would normative comparisons; and that (2) in the sample as a whole, mothers’ self-reported borderline features (affective instability, identity disturbance, negative relationships, and self-harm) would be significantly negatively correlated with their adaptive caregiving, and significantly positively correlated with their frightened/disoriented behavior, and role reversal. Method Participants: The sample included n = 36 low-SES children age 4-7 whose mothers have BPD and n = 34 demographically matched normative comparisons. Measures: Demographics were assessed with the Mt Hope Family Center Demographic Questionnaire (MHFC, 1995). There were no significant differences between groups on demographic variables. See Table 1. Mood disorders Current major depression, bipolar disorder and dysthymia were assessed with the SCID-I clinical interview (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams, 1996); 41% of the BPD mothers and 0% of the comparisons were diagnosed with a current mood disorder. Borderline personality disorder was assessed with the SCID-II clinical interview (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997). Borderline features. Affective instability, identity disturbance, negative relationships, and self-harm were assessed with the selfreport Personality Assessment Inventory Borderline Features Scale (Morey, 1991). Mother-child interaction. A maternal caregiving composite (sensitivity, autonomy support, hostility reverse-scored), fearful/disoriented behavior (e.g., mother looks dazed or projects very alarming content onto the puzzle solving task), and role reversal (e.g. child behaves as if he/she were the parent telling the mother what to do, or the mother behaves as if she was the child’s peer playing and giggling together with no appropriate discipline),were coded reliably from 10-minute videotapes of puzzle-solving interactions using the Qualitative Ratings of Parent/Child Interaction (Cox, February, 1997). Results Hypothesis (1). The overall test of group differences was significant using a MANCOVA, Wilks’s approximate F (3, 63) = 5.83, p < .001, η2 = .22, observed power = .94. There were also significant univariate group differences for maternal caregiving, fearful/disoriented behavior and role reversal. Mothers with BPD demonstrated less adaptive caregiving, more fearful/disoriented behavior, and more role reversal. See Table 2. Hypothesis (2). Maternal affective instability, identity disturbance and negative relationships, were negatively correlated with the maternal caregiving composite and positively correlated with role reversal. Identity disturbance was positively correlated with maternal fearful/disoriented behavior, and self-harm was marginally significantly correlated with maternal fearful/disoriented behavior. See Table 3. Discussion The study finds that maternal BPD exerts a risk for offspring beyond infancy. Mothers with BPD may find that their symptoms affect their moment-by-moment functioning with their child, making consistent and empathic care to support a goal-corrected partnership challenging. Mothers with BPD not only displayed maladaptive caregiving, they also demonstrated fearful/disoriented behavior, and used the child to meet their own needs in a role reversal. Without an adequate goal-corrected partnership, children may not have access to maternal support and guidance as they try to regulate their own emotions and behavior, relate to peers and function in school. Along with the narratives of the childcaregiver relationship which mirror current findings at the level of representation (Macfie & Swan, 2009), the development of psychopathology, including BPD, may be more likely for children whose mothers have BPD. Indeed, maternal hostility in infancy and role reversal at 42 months, both included in the current study with BPD offspring, predicted BPD symptoms at age 28 in a longitudinal study of a sample at risk due to poverty (Carlson, Egeland, & Sroufe, 2009). Furthermore, in the same longitudinal study, disorganized attachment in infancy, found in offspring of women with BPD (Hobson et al., 2005), also predicted BPD symptoms at age 28 (Carlson et al., 2009). Because of the increased risk of developing a full diagnosis of BPD in offspring compared to Carlson et al.’s poverty sample, longitudinal study of offspring of women with BPD may further illuminate pathways to resilience vs. BPD. Longitudinal study should also prove of unique interest to developmental psychopathologists seeking to understand more about how atypical development informs normative development and vice versa. We may then be in a position to design preventive interventions for BPD. References Bowlby, J. (1969/1982). Attachment and loss. Vol. I. Attachment. New York: Basic Books. Carlson, E. A., Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (2009). A prospective investigation of the development of borderline personality symptoms. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 1211-1334. Cox, M. J. (February, 1997). Qualitative ratings of parent/child interaction at 24 months of age. Unpublished manuscript. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Crandell, L. E., Patrick, M., & Hobson, R. P. (2003). 'Still-face' interactions between mothers with borderline personality disorder and their 2month-old infants. British Journal of Psychiatry, 183, 239-247. First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (1996). User's guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I disordersresearch version. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Benjamin, L. S. (1997). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders: SCID-II. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Grant, B. F., Chou, S. P., Goldstein, R. B., Huang, B., Stinson, F. S., Saha, T. D., . . . Ruan, W. J. (2008). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 533-545. Hobson, R. P., Patrick, M., Crandell, L., Garcia-Perez, R., & Lee, A. (2005). Personal relatedness and attachment in infants of mothers with borderline personality disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 17, 329-347. Macfie, J. (2009). Development in children and adolescents whose mothers have borderline personality disorder. Child Development Perspectives, 3, 66-71. Macfie, J., & Swan, S. A. (2009). Representations of the caregiver-child relationship and of the self, and emotion regulation in the narratives of young children whose mothers have borderline personality disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 993-1011. MHFC. (1995). Mt. Hope Demographic Interview. Unpublished manuscript. University of Rochester. Morey, L. C. (1991). Personality Assessment Inventory. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., DeLuca, C. J., Hennen, J., Khera, G. S., & Gunderson, J. G. (1998). The pain of being borderline: Dysphoric states specific to borderline personality disorder. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 6, 201-207. Table 1. Child age, child verbal abilities, and demographic differences between the BPD and normative comparison groups Variable Whole sample BPD Comparisons t N = 70 n = 36 n = 34 M (SD) M (SD) M (SD) Child Age (years) 5.37 (0.90) 5.31 (0.90) 5.42 (0.90) 0.52 Verbal Ability (PPVT) 102.67 (13.65) 100.06 (15.05) 105.29 (11.74) 1.62 Family Yearly Income ($) 31,841 (27,855) 30,018 (19,192) 33,664 (34,633) 0.55 # Adults in Home 1.83 (0.78) 1.83 (0.79) 1.83 (0.79) 0.00 # Children in Home 2.47 (1.16) 2.63 (1.26) 2.31 (1.05) 1.13 λ2 Child Gender (girls) 50% 54% 46% 0.51 Child Minority Ethnic Background 11% 11% 11% 0.00 Mother Graduated High School or GED 89% 83% 94% 2.26 Mother Has Partner 77% 77% 77% 0.00 Table 2. Group differences in mother-child interaction variables: univariate F-tests, effect size and Mother-child interaction Whole BPD Comparisons variable sample N = 70 n = 36 n = 34 M(SD) M(SD) M(SD) Maternal caregiving 5.73 4.08 (3.97) 7.47 (4.34) composite (4.46) Mother-child role reversal 2.41 3.06 (1.45) 1.74 (0.93) (1.39) Maternal 1.29 1.47 (1.23) 1.09 (0.38) fearful/disoriented (0.93) behavior *p < .05; **p < .01; *** p < .001. observed power F(df) η2 Observed power F(1, 65) 9.59** .13 .86 15.41*** .19 .97 4.25* .06 .53 Table 3. Correlations between maternal borderline features and mother-child interaction variables Maternal borderline features Mother-child interaction variable Affective instability Identity disturbance Negative relationships Maternal caregiving composite -.31** -.34** -.40*** Mother-child role reversal .44*** .31** .42*** Maternal fearful/disoriented behavior .19 .29* .10 † p < 10; *p < .05; **p ≤.01; *** p ≤.001. Self-harm -.11 .23† .14