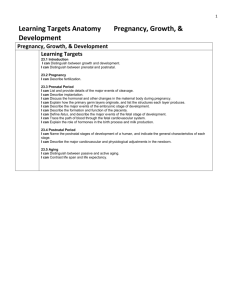

Pregnancy Labelling Evaluation

advertisement