Islamic fasting and Multiple Sclerosis

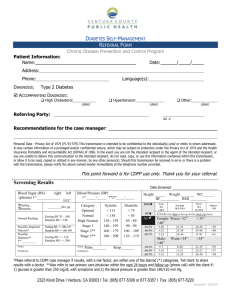

advertisement

Islamic fasting and Multiple Sclerosis Soodeh Razeghi Jahromi1, Mohammad Ali Sahraian1 , Fereshteh Ashtari2, Hormoz Ayramloo3, Massoud Etemadifar2, Majid Ghaffarpour4, Ehsan Mohammadiannejad5, Shahryar Nafissi6, Alireza Nickseresht7, Vahid Shayegannejad8, Mansoreh Togha1 , Hamid Reza Torabi9, Shadi Ziaie10 1. MS Research Center- Neuroscience Institute, Sina Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. 2. Department of Neurology, Azahra Hospital, Esfahan University of Medical Sciences. 3. Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. 4. Iranian Center for Neurological Research, Imam Khomini Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. 5. Department of Neurology, Golestan Hospital, Ahwaz University of Medical Sciences. 6. Department of Neurology, Shariati Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. 7. Department of Neurology, Namazi Hospital, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. 8. Department of Neurology, Kashani Hospital, Esfahan University of Medical Sciences 9. Jam Hospital, Iranian MS Society 10. Department of Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, Shahid Beheshti University of medical Sciences Corresponding author: Mohammad Ali Sahraian, MD MS Research Center, Neuroscience Institute, Sina Hospital, Hasan abad Square, Tehran-Iran Tel: +98 21 66348571 Fax: +98 21 66348570 Email: msahrai@sina.tums.ac.ir 1 Abstract Background: The month-long daytime Ramadan fasting pose a major challenge to multiple sclerosis (MS) patients in Muslim countries. Physician should have practical knowledge on the implications of fasting on MS. In this article, we present a summary of a symposium on Ramadan fasting and MS. In this symposium, we aimed to review the effect of fasting on MS and suggest practical management guides. Discussion: Generally, fasting is possible for most stable patients. Proper amendment of drug regimen, careful monitoring of clinical symptoms, as well as providing patients with available evidences on fasting and MS are important parts of clinical management. Current evidences from experimental studies suggest that calorie restriction prior to disease induction reduces inflammation and subsequent demylination and as a result attenuates disease severity. A recent study examining the effect of fasting on MS showed that fasting had no unfavorable effect on the course of disease in patients with mild disability (disability status scale ≤3). More studies are needed to assess the effects of symptomatic treatment and the duration of fasting on MS. However, a majority of experts believed that during fasting especially in summer, some of MS symptoms including fatigue, fatigue perception, dizziness, spasticity, cognitive problems, weakness, vision, balance, and gait might worsen; but usually return to normal level during feast time. There was also a general consensus that fasting is not safe for patients on high dose of anticonvulsants, antispastics, and corticosteroids, patients with coagulopathy or active disease, during attacks and in patients with disability status scale ≥7. Summary: MS patients should be managed individually. Indeed, fasting in MS patients is a challenge that is directly associated with the patients’ will. Keywords: Ramadan fasting, multiple sclerosis, calorie restriction 2 Introduction Several religions recommend times of fasting. A 2009-demographic study reported that 23% (1.57 billion) of the world’s population are Muslims [1]. This percent is growing by 3% per year. Ramadan fasting is considered as one of the five pillars of Islam and day-time fasting during the holy month of Ramadan is obligatory for all healthy adults. Muslims are forbidden from eating, drinking, smoking, and sexual relationship from husk to down. Travelers, menstruating, pregnant, and lactating women, children, particular sick persons and debilitates are exempt from fasting [2]. However, many Muslims who are eligible for exemption including individuals with mild, moderate, and severe medical conditions choose to fast. More ever, recent evidences revealed that there is no contraindication to Islamic fasting for patients with mild coronary artery disease, valvular problems, stable asthma, many of the type-2 diabetes, asympthomatic peptic ulcer, and intestinal motility disorders. Consequently, the Muslim patients are seeking advice about the safety and feasibility of fasting[3] Multiple sclerosis (MS) is one of these medical conditions. MS is a chronic demyelinating disease with an unclear etiology that affect approximately two-and-a-half million individuals worldwide and identified as the most common debilitating neurological disease in young adults[4]. MS is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease of the central nervous system (CNS) that, in the most severe cases, can lead to irreversible clinical disability[5]. The concern for Muslim MS patients is weather Ramadan fasting might have an unfavorable effect on disease course. This debate became more challenging after the work of Esquifino et al. on the animal model of MS, known as Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis (EAE). In human and animal studies, the effect of fasting on health is commonly studied in three forms: calorie restriction (CR), alternate-day fasting (ADF) and dietary restriction. ADF and CR may induce similar metabolic and physiological changes. Esquifino et al. reported that Calorie Restriction (CR) improves signs of EAE[6]. Hence, we aimed to review the opinions of neurologist involving in management of patients with MS, about the medical impact of Ramadan fasting on this disease, irrespective of their religious believes. For this purpose we firstly reviewed the current evidences about fasting and multiple sclerosis. Secondly, we presented a coincise summary of the points discussed in the mini-symposium on the effect of fasting on MS patients. In the mentioned symposium we asked the neurologists, nutritionists, and clinical pharmacists to present a summary of available evidences, as well as their clinical experiences about fasting and MS. Consequently we aimed to provide 3 practical guidance for MS patients who decided to fast with respect to their general health, disability score, level of activity, sex, weight, symptoms and job. Discussion Information has been sought through the Cochrane and PubMed data bases. All relevant abstracted reports have been considered from the initiation of these data bases to June 2013, combining the term “Ramadan” (476 entries) with terms specific to each of the topics under investigation. Also all relevant abstract about “ketogenic diet” (703 items), as well as about“calorie restriction” or “fasting” combined with the terms “neuroprotection” and” immunity” (38 items) were reviewed. Fasting in animal studies CR with nutritional maintenance has been proposed to extend life span in the following species: fruit fly, nematode, zebra fish, spider, rodent, and rotifer [7]. In addition to slowing the aging process, CR has been demonstrated to delay the onset of several diseases including: atherosclerosis, cardiomyopathies, renal disease, diabetes, cancers, and respiratory disease [7]. Among neurological disease, fasting and more generally CR represents the first effective treatment for epilepsy in medical history [8]. CR results in an increase in serum level of the ketone body, Beta-hydroxybutyrate. This rise in beta-hydroxybutyrate level correlates with a significant reduction in the vulnerability of hippocampal neurons to kainite injection. In 1920s, the ketogenic characteristics of calorie restriction lead to development of high-fat, lowcarbohydrate ketogenic diet [8]. Antiepileptic properties of KD could be explained in part with its ant-apoptotic and anti-oxidative properties. Recent studies suggested that nuclear clusterin, a proapoptotic protein, did not accumulate in the hippocampus of KD-fed mice induced with kainic acid (KA) [9]. KD also reduced the KA-induced cell death in the hippocampus by reducing caspase-3 level and blocking the dissociation of Bad from 14-3-3 proteins [10]. Noh et al. performed an in-vitro study on the effect of acetoacetate (AA) on glutamate cytotoxicity in a rat primary hippocampal neurons and mouse hippocampus cell line (HT22). Pretreatment with AA reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production of HT22 cell line. AA also decreased the appearance of popidium iodine-positive and annexin V-positive HT22 cells which are representative of necrosis and apoptosis [11]. 4 Accumulating data suggested that the beneficial effects of CR were not limited to ketogenic properties. Calorie restriction per se have profound neuroprotective effects in animal models relevant to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders like Huntington's, Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and stroke. Opalach K et al. investigated the effect of 40% life-long calorie restriction on age-related oxidative damages of peripheral nerves. They found that CR ameliorates the age-related accumulation of cross-linked and oxidized substances in the peripheral nerves. CR also attenuated age-related nuclear factor kB (NFkB), phospho-IkB, and tumor necrotizing factor α (TNF-α) increments [12]. Age-related oxidation of myelin polyunsaturated fatty acids results in the formation of hydroxyalkenals and hydroperoxidase, like 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) and malondialdehyde (MDA) which reacts with proteins and change their surface hydrophobicity. CR suppressed age-related increase in MDA-adducted proteins of siatic nerves. CR also reduced HNE-positive area throughout axonal and glial compartments [12]. Several other molecular and cellular mechanisms were also proposed for the neuroprotective action of CR including: decrease mitochondrial production of free radicals [13], the promotion of antioxidant defense [8], induction of bioenergetics [8, 14], elevation of sirtuin activity [15], rise in neurotrophic factors activity [8], increase of protein chaperone activity [8], enhancement of neurogenesis [8], imposing anti-inflammatory properties, [8] , reduction of leptin level [16], and reduction of oligodendrocyte apoptosis [7]. Each of which, make CR beneficial in protecting against MS and EAE. Up to the best of our knowledge, there are only three studies on CR in animal model of MS-experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). In two of these, Esquifino et al. found that restricting energy intake by 33% or 66% from 15 days prior to EAE induction, would decrease the severity of disease in rats [17-18]. Rats in the later group were totally protected against EAE. Subjecting to 66% CR led to impaired lymphocyte proliferation, decreased CD4+ cells in lymphoid organs, and suppressed Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) production. In Piccio et al. study, mice were subjected to 40% calorie restriction from five weeks prior to disease induction. They observed comparable beneficial effect on the course of disease[19]. In the mentioned study CR worked through the enhancement of endogenous glucocorticoid production, but not through immune system suppression. In above three mentioned studies, the following mechanisms have been proposed for the beneficial effects of CR: Concept 1: Improving the function of immune system 5 Long-term calorie restriction improves T-cell function and delays immune senescence. According to Squifino et al. study, 66% CR resulted in modification of 24-hour rhytmicity of T-B lymph nodes, T lymphocytes, CD4+-CD8+ and CD4+ cells subsets function, as well as, lymph node mitogenic responses to Concanavalin A and lipopolysaccaride. Furthermore, mean values of Submaximally lymph node Con A response and CD4+ cell number increased. On the other hand, the number of B-cells and the secretion of IFN-γ decreased[20]. In Piccio et al. study, 40% calorie restriction ameliorated EAE signs, without suppression of T-cell proliferation. Long term CR reduced susceptibility to infectious disease by enhancing T-cell function [19]. Collectively, applying calorie restriction prior to disease induction, protect against EAE, by improving T-cell function. Concept 2: CR enhances glucocorticoids production Glucocorticoids have inhibitory effects on inflammatory gene expression [21]. Systemic corticosteroid administration is known as standard treatment in MS exacerbation [22]. In rodent, treatment with exogenous glucocorticoids blocks EAE[23]. In Piccio et al. study, four weeks CR increased corticosterone level[19]. Interestingly, endogenous production of corticosterone would avoid side-effects reported in exogenous administration of steroids[19]. Concept 3: imposing immunomodulatory effect Interleukin 6 (IL-6) can be produced by adipose tissue. Four weeks of CR reduced body fat and consequently, IL-6 level. IL-6 has critical role in EAE induction. EAE cannot be induced IL-6 in mice [19]. IL-6 together with Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), has been reported to inhibit the production of T regulatory cells, results in suppression of T-helper 17 (Th-17) gene expression [19]. Expression of Th-17 known as one of the main features of MS [24]. Fasting in human studies There are limited evidences about fasting, especially Islamic fasting and MS. However, the immunomodulatory and anti-oxidative properties of fasting have recently been the subjects of scientific investigations. Effects of fasting on immune system in human beings 6 Ahmed T et al. performed a study on 6-weeks 30% or 10% CR in 40 healthy overweight men and women. They reported that delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) response, which reflects cell-mediated immunity were increased significantly in both 10 or 30% CR groups. 30% CR also reduced prostaglandine E2 (PGE2)production and the Tcell proliferative response to ant-CD3. More ever the observed that proliferative T-cell response to T-cell receptor antibody and T-cell mitogens were increased in both 10 and 30% CR groups. They concluded that CR can improve T-cell function in human as well [25]. Pali AA et al compared the immune function of 12 obese adolescents with healthy normal weights. They found that IFN- γ/ IL-4 ratio in CD4+ cells was higher in obese individuals. The proposed the idea that the antigen presenting cell-regulatory T-cell-CD4+ lymphocyte axis might be affected by calorie disturbance [26]. In a randomized controlled trial sponsored by National Institute on Aging (U.S.A), effect of CR on human has been studied. The preliminary results showed that 20-25% CR for 6-12 months reduced leptin, T3 and fasting insulin level. CR also reduced DNA damages as a marker of oxidative insult [27]. Fraser D.A. et al performed series of studies on the effect of fasting on rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease which shared immunological features with MS. They reported that 7-day fasting reduced CD4+ lymphocyte activity and induced IL-4 production [28]. Latifynia et al. assessed the effect of Ramadan fasting on innate immunity (neutrophil tetrazolium reaction and phagocytosis opsonization). They conducted that the innate immune response increases after fasting [29]. Fasting and multiple sclerosis Due to the best of our knowledge, there are only two studies on Ramadan fasting in MS patients. El-Dayem and Zyton performed a study on 30 MS patients (15-45 years) with disability status scale (EDSS) <3. After one year, no significant differences were observed in relapsing rate, EDSS score, and gadolinium enhanced lesions on MRI between fasted and not-fasted groups [30]. Saadatnia et al. performed a study on 80 patients (>17 years) with EDSS ≤3. After 6 months, no significant differences in EDSS or frequency of clinical relapses were noted between fasted and not fasted groups. The authors concluded that fasting does not impose unfavorable effect in short term. The authors also stated that, the reduction of food intake especially of fat during Ramadan might enhance antioxidative activity and consequently may protect against relapse after the end of Ramadan. The authors also suggested that the reduction of uric acid level during Ramadan fasting could protect against MS relapse. Uric acid is formed as a metabolite of purine. It also concentrated following dehydration during fasting. Serum uric acid level was lower in 7 MS patients, comparing to healthy individuals [31] . In the followings we presented the concise extract from the points discussed in the mini symposium. Question 1: Is it safe for MS patients to fast? Although the effect of fasting on MS is not clear, Islamic fasting is generally considered to be safe in most MS patients. However, making a general recommendation about the safety of fasting to MS patients is not possible. Decision should be made with respect to individual conditions. According to previous studies, Ramadan fasting does not have negative effect on MS patients with mild disability in short term [30-31]. Patients should be monitored for individual clinical symptoms (e.g. fatigue, energy level …), type of MS, level of disability, systemic disease, medication, and social level. Patients’ education is an important part of management. They should be informed about symptoms of exacerbation. Question 2: does fasting affect MS symptoms? One of the main concerns is whether fasting affects MS symptoms. Although previous studies reported no shortterm unfavorable effect of fasting on course of disease [30-31]; it is believed that during fast time, some of the symptoms of MS might worsen. However, they return to the usual level during feast time. The symptoms include: fatigue, dizziness, spasticity, cognitive problems, weakness, vision, balance, and gait. In Previous studies on healthy adults, fasting induced fatigue and also fatigue perception. In a study performed to assess the effect of Ramadan fasting on muscle power and fatigue in healthy football playerafter 2 and 4 weeks of fasting, muscle power was decreased and fatigue was increased in evening. Moreover, perceived exertion and fatigue is higher during Ramadan [32]. It seems that in MS patients who spiritually believe in fasting, perceived fatigue is less common. However in patients who observe fasting as an obligation, perceived fatigue might be more prevalent. More ever, heavy workers complain about tiredness and dizziness during Ramadan fasting which may be due to dehydration [33]. According to previous studies fasting had no effect on vision in healthy adults. In healthy middle-aged volunteers, fasting does not affect intraocular pressure, refractive error or visual activity values[34]. However, it is believed that, unlike healthy adults, fasting might affect vision in MS patients. 8 In a study on judo athletes, Ramadan fasting had negative effect on the postural control. During Ramadan, the unipodal (on one foot) and bipodal sway velocity was decreased in judo athletes [35]. Studies on the effects of Ramadan fasting on the mood profile stated mixed results. In a study on 8 middle-distance runners, 30 days fast negatively affect mood profile [36]. In contrast, in another study on 20 young football players, mood profile did not show significant differences during and after Ramadan comparing before Ramadan [37]. In another study on healthy athletes, the changes in cognitive functions were studied during Ramadan. Cognition domains include: Psychomotor functions, vigilance, visual learning, verbal learning, memory, and executive function. Comparison of cognitive function in the morning with the afternoon showed significant decline in psychomotor function, visual and verbal learning and memory. The effect size was greater during Ramadan [38]. Question 3: Does fasting affect MS exacerbation? It is also believed that according to current evidences, Ramadan fasting neither protect nor provoke MS attacks. However, more prospective studies are needed to follow clinical conditions after Ramadan. Question 4: Do symptomatic treatments prohibit fasting? One of the other most frequently asked question about fasting in MS patients is whether symptomatic treatments prohibit fasting. It is believed that, for some drugs amending the drug regimen is possible during Ramadan by substituting oral agents with injection, prescribing slow-release or long-acting drugs once or twice at night. However, accurate distribution of drugs which prescribed twice a day or three times per day between suhoor and Iftar is difficult to achieve. When dosing and the time span between the doses are changed, alteration might affect the serum level of drug and consequently its tolerance and efficacy [3]. Furthermore, drug-food interactions might result in delayed, reduced or increased bioavailability of a drug. Also, changes in circadian rhythm, sleep disturbances, emotional and physical stress might influence the drug pharmacokinetics. In a study even the change in the timing of a single dose of valproate (800 mg) during Ramadan, increased the frequency of seizure significantly [39]. The problem becomes more notable in patients on polytherapy. Table 1 summarized the circadian variation in pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of mostly prescribed medication in MS, as well as their drug-food interaction 9 It is believed that for patients on high dose of antispastic drugs or antiepileptic drugs and patients who are obliged to take their drugs more than twice a day, fasting is not feasible. Similarly if changing the drug has negative effect on activity of daily living or level of disability, fasting should be avoided. There is also a general consensus that amending the drug regimen should be started before Ramadan. In a study on 114 epileptic patients, amending drug regimen according to timing of Suhoor and Iftar did not prevent from an increase in seizure frequency [40]. Question 5: Does consuming disease modifying drugs (DMD) prohibit fasting? Another important question is whether consuming disease modifying drugs (DMD prohibit fasting. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Interferons and Glatiramer acetate are not affected by food consumption and it seems that plasma drug concentration-time curve of the Interferons and Glatiramer acetate did not affected by prolonged fasting [41-42]. Up to the best of our knowledge no data is available about the effect of fasting on Fingolimod pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. However, according to neurologists view fasting is not recommended for patients who experience severe flu-like symptoms (fever, chills, sweating, muscle aches, fatigue) following injection. Fasting might affect pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of immunosuppressants. Also, drug-food interactions may result in increased, or reduced and delayed systemic availability of immunosuppressants. Table 2 represented the effects of fasting on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of immunosuppressants and manufacturer’s recommendation for their consumption [43]. No pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics reactions between cyclophosphamide and foods were reported. However, as cyclophosphamide is mainly excreted by urine, limited access to liquids during fasting may have negative effect on the drug level [44]. Question 6: Is the level of disability (EDSS score) important when a patient decides to fast? Whether the level of disability (EDSS score) is also important when a patient decide to fast, was also discussed. As mentioned before, considering Saadatnia et al. and El-Dayem result, fasting is known to be safe in patients with mild disability (EDSS≤ 3). Patients with higher levels of disability are less physically active, and consequently are more prone to constipation, upper urinary tract infection, bedsore, and diverticulitis. Dehydration during prolonged fasting might potentially aggravate the mentioned symptoms. It is recommended that patients with EDSS≥7 avoid fasting. Question 7: Does the type of MS interfere with your decision about fasting? 10 It is believed that regardless of type of MS, patients with highly active disease should be prohibited from fasting. Also patients who experienced attacks during or after Ramadan fasting should avoid fasting. During attacks, due to high dose of corticosteroid therapy, fasting is not recommended. Question 8: Is fasting during summer safe for MS patients? The duration of fasting is another concern. The fasting demands at high latitudes during winter is different from those at equatorial region during summer [45]. Increasing the number of fasting hours during summer, may increase the negative impacts of fasting. Individualized monitoring of MS patients who observed fasting during summer and avoiding dehydration is recommended. Question 9: Is it safe for MS patients to fast for a whole month? Also the interval between fasting days should be set according to patient’s individual condition. Appropriate sleep, adequate and proper food and fluid intake during feast hours are recommended. According to Saadatnia et al. results, fasting for 13 hours a day for 28 days has no unfavorable short-term effects [31]. Summary Fasting during the holy month of Ramadan is a respected obligation for the healthy Muslim adults. Fasting in MS patients has recently attracted the physicians’ attention. The experimental studies were focused on protective role of intermittent fasting in MS. Human studies on fasting in MS patients, especially Islamic fasting are very rare. So far there are insufficient evidences to suggest fasting may be effective in protecting against or controlling MS signs. However, according to the current evidence, fasting had no unfavorable effect on course of disease. In current meeting, there is a general consensuses that observing Ramadan fasting is possible for many of the MS patients. Careful monitoring of general and clinical condition, as well as precise management of drug regimen, diet, and sleep pattern would help to reduce possible negative effects of fasting. However, in the following situations fasting is not recommended: 1. During attacks 2. Patients on high dose of antispastic and anticonvulsant drugs 3. Patients with coagulopathy 11 4. Patients with EDSS≥7 5. Patients with active disease Fasting especially during summer might negatively affect fatigue, weakness, vision, balance, and gait. Individualized recommendation should be made with respect to energy level and general well being of the patient. It seems that MS patients who spiritually believed in fasting as a sacred obligation, report fewer negative impact of fasting on MS signs. For example, perceived fatigue is increased during fasting. Spiritual belief might reduce fatigue perception. This hypothesis might be expandable to other symptoms of the disease. On the other hand, in patients who find themselves obliged to fast, the perception of negative impacts of fasting might be higher. Patients should be provided with scientific evidence about the effects of fasting on health issues before Ramadan to decide about fasting themselves. More researches are needed to prepare a detailed guideline for MS patients. Our meeting is an attempt to help physicians for better management of MS patients who decide to fast, as well as to pave the ground for more researches in this field. List of abbreviations AA: acetoacetate ADF: Alternate-day fasting CNS: Central nervous system CR: Calorie restriction DMD: Disease modifying drugs EAE: Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis EDSS: Expanded disability status scale HNE: 4-hydroxynonenal KD: ketogenic diet 12 IFN-γ: Interferon gamma IL-6: Interleukin 6 MDA: malondialdehyde MS: Multiple sclerosis NFkB: nuclear factor kB Th-17: T-helper 17 TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta TNF-α: tumor necrotizing factor α Competing interests None of the authors had any financial or personal conflicts of interests. Authors’ contribution Since it was an expert meeting, all authors contributed to the article equally and their names are presented in alphabetic order. SRJ: wrote the primary draft MAS: Proposed the idea, revised the primary draft Acknowledgements The meeting and accommodations was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from CinnaGen Company. The authors would like to thank the sponsor for the logistic support during the meeting and also thank the “Research Development Center” of Sina hospital in for language editing of the manuscript 13 References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. Al-Arouj M, Assaad-Khalil S, Buse J, Fahdil I, Fahmy M, Hafez S, Hassanein M, Ibrahim MA, Kendall D, Kishawi S: Recommendations for management of diabetes during Ramadan update 2010. Diabetes Care 2010, 33:1895-1902. Azizi F: Islamic fasting and health. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 2010, 56:273-282. Beshyah SA, Fathalla W, Saleh A, Al-Kaddour A, Noshi M, Al Hatheethi H, Al-Saadawi N, Elsiesi H, Amir N, Almarzouqi M: Ramadan Fasting and The Medical Patient: An Overview for Clinicians. Ibnosina Journal of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences 2010, 2:240-257. MS? NmssAMWg: http://wwwnationalmssocietyorg/about-multiple-sclerosis/what-we-knowabout-ms/who-gets-ms/indexaspx 2011. Wingerchuk DM, Lucchinetti CF, Noseworthy JH: Multiple sclerosis: current pathophysiological concepts. Lab Invest 2001, 81:263-281. Esquifino AI, Cano P, Jimenez V, Cutrera RA, Cardinali DP: Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in male Lewis rats subjected to calorie restriction. J Physiol Biochem 2004, 60:245-252. Maalouf M, Rho JM, Mattson MP: The neuroprotective properties of calorie restriction, the ketogenic diet, and ketone bodies. Brain research reviews 2009, 59:293-315. Maalouf M, Rho JM, Mattson MP: The neuroprotective properties of calorie restriction, the ketogenic diet, and ketone bodies. Brain research reviews 2009, 59:293-315. Noh HS, Kim DW, Kang SS, Cho GJ, Choi WS: Ketogenic diet prevents clusterin accumulation induced by kainic acid in the hippocampus of male ICR mice. Brain research 2005, 1042:114118. Noh HS, Kim YS, Kim YH, Han JY, Park CH, Kang AK, Shin HS, Kang SS, Cho GJ, Choi WS: Ketogenic diet protects the hippocampus from kainic acid toxicity by inhibiting the dissociation of bad from 14‐3‐3. Journal of neuroscience research 2006, 84:1829-1836. Noh HS, Hah YS, Nilufar R, Han J, Bong JH, Kang SS, Cho GJ, Choi WS: Acetoacetate protects neuronal cells from oxidative glutamate toxicity. Journal of neuroscience research 2006, 83:702-709. Opalach K, Rangaraju S, Madorsky I, Leeuwenburgh C, Notterpek L: Lifelong calorie restriction alleviates age-related oxidative damage in peripheral nerves. Rejuvenation research 2010, 13:65-74. Cheng CM, Hicks K, Wang J, Eagles DA, Bondy CA: Caloric restriction augments brain glutamic acid decarboxylase‐65 and‐67 expression. Journal of neuroscience research 2004, 77:270-276. Swerdlow RH: Treating neurodegeneration by modifying mitochondria: potential solutions to a “complex” problem. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2007, 9:1591-1604. Guarente L: Calorie restriction and sirtuins revisited. Genes & development 2013, 27:20722085. Rogozina OP, Bonorden MJ, Seppanen CN, Grande JP, Cleary MP: Effect of chronic and intermittent calorie restriction on serum adiponectin and leptin and mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Prevention Research 2011, 4:568-581. Esquifino A, Cano P, Jimenez V, Cutrera R, Cardinali D: Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in male Lewis rats subjected to calorie restriction. Journal of physiology and biochemistry 2004, 60:245-252. 14 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. Esquifino AI, Cano P, Jimenez-Ortega V, Fernández-Mateos MP, Cardinali DP: Immune response after experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in rats subjected to calorie restriction. J Neuroinflammation 2007, 4:6. Piccio L, Stark JL, Cross AH: Chronic calorie restriction attenuates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Leukoc Biol 2008, 84:940-948. Esquifino AI, Cano P, Jimenez-Ortega V, Fernandez-Mateos MP, Cardinali DP: Immune response after experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in rats subjected to calorie restriction. J Neuroinflammation 2007, 4:6. Adcock IM, Caramori G: Cross-talk between pro-inflammatory transcription factors and glucocorticoids. Immunology and Cell Biology 2001, 79:376-384. Myhr K, Mellgren S: Corticosteroids in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Acta neurologica Scandinavica 2009, 120:73-80. Bolton C, O’Neill J, Allen S, Baker D: Regulation of chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by endogenous and exogenous glucocorticoids. International archives of allergy and immunology 1997, 114:74-80. Du C, Liu C, Kang J, Zhao G, Ye Z, Huang S, Li Z, Wu Z, Pei G: MicroRNA miR-326 regulates TH-17 differentiation and is associated with the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Nature immunology 2009, 10:1252-1259. Ahmed T, Das SK, Golden JK, Saltzman E, Roberts SB, Meydani SN: Calorie Restriction Enhances T-Cell–Mediated Immune Response in Adult Overweight Men and Women. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 2009, 64:1107-1113. Pali A, Paszthy B: Changes of the immune functions in patients with eating disorders]. Ideggyógyászati szemle 2008, 61:381. Fontana L, Coleman R, Holloszy J, Weindruch R: Calorie restriction in non-human and human primates. HANDBOOK OF THE BIOLOGY OF AGING 2010. Fraser D, Thoen J, Reseland J, Førre Ø, Kjeldsen-Kragh J: Decreased CD4+ lymphocyte activation and increased interleukin-4 production in peripheral blood of rheumatoid arthritis patients after acute starvation. Clinical rheumatology 1999, 18:394-401. Latifynia A, Vojgani M, Gharagozlou M, Sharifian R: Neutrophil function (innate immunity) during Ramadan. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad: JAMC 2008, 21:111-115. Abd El-Dayem SM, Zyton HAH: The Effect of Ramadan Fasting on Multiple Sclerosis. Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry & Neurosurgery 2012, 49. Saadatnia M, Etemadifar M, Fatehi F, Ashtari F, Shaygannejad V, Chitsaz A, Maghzi AH: Shortterm effects of prolonged fasting on multiple sclerosis. European neurology 2009, 61:230-232. Chtourou H, Hammouda O, Chaouachi A, Chamari K, Souissi N: The effect of time-of-day and Ramadan fasting on anaerobic performances. International journal of sports medicine 2012, 33:142. Schmahl F, Metzler B: The health risks of occupational stress in islamic industrial workers during the Ramadan fasting period. Polish journal of occupational medicine and environmental health 1991, 4:219. Assadi M, Akrami A, Beikzadeh F, Seyedabadi M, Nabipour I, Larijani B, Afarid M, Seidali E: Impact of Ramadan fasting on intraocular pressure, visual acuity and refractive errors. Singapore medical journal 2011, 52:263-266. Souissi N, Chtourou H, Zouita A, Dziri C, Souissi N: Effects of Ramadan intermittent fasting on postural control in judo athletes. Biological Rhythm Research 2013, 44:237-244. Chennaoui M, Desgorces F, Drogou C, Boudjemaa B, Tomaszewski A, Depiesse F, Burnat P, Chalabi H, Gomez-Merino D: Effects of Ramadan fasting on physical performance and 15 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. metabolic, hormonal, and inflammatory parameters in middle-distance runners. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 2009, 34:587-594. Chtourou H, Hammouda O, Souissi H, Chamari K, Chaouachi A, Souissi N: The effect of Ramadan fasting on physical performances, mood state and perceived exertion in young footballers. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine 2011, 2. Tian H-H, Aziz A-R, Png W, Wahid M, Yeo D, Png A-L: Effects of fasting during Ramadan month on cognitive function in Muslim athletes. Asian Journal of Sports Medicine 2011, 2. Aadil N, Fassi-Fihri A, Houti I, Benaji B, Ouhakki M, Kotbi S, Diquet B, Hakkou F: Influence of Ramadan on the pharmacokinetics of a single oral dose of valproic acid administered at two different times. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 2000, 22:109-114. Gomceli YB, Kutlu G, Cavdar L, Inan LE: Does the seizure frequency increase in Ramadan? Seizure 2008, 17:671-676. Sturzebecher S, Maibauer R, Heuner A, Beckmann K, Aufdembrinke B: Pharmacodynamic Comparison of Single Doses of IFN-beta 1a and IFN-beta 1b in Healthy Volunteers. Journal of interferon & cytokine research 1999, 19:1257-1264. Messina S, Patti F: The pharmacokinetics of glatiramer acetate for multiple sclerosis treatment. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology 2013, 9:1349-1359. Singh BN, Malhotra BK: Effects of food on the clinical pharmacokinetics of anticancer agents. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2004, 43:1127-1156. De Jonge ME, Huitema AD, Rodenhuis S, Beijnen JH: Clinical pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide. Clinical pharmacokinetics 2005, 44:1135-1164. Maughan RJ, Zerguini Y, Chalabi H, Dvorak J: Achieving optimum sports performance during Ramadan: Some practical recommendations. Journal of Sports Sciences 2012, 30:S109-S117. Singh BN: Effects of food on clinical pharmacokinetics. Clinical pharmacokinetics 1999, 37:213255. Charman WN, Porter CJ, Mithani S, Dressman JB: Physicochemical and physiological mechanisms for the effects of food on drug absorption: the role of lipids and pH. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 1997, 86:269-282. Berry D, Millington C: Analysis of pregabalin at therapeutic concentrations in human plasma/serum by reversed-phase HPLC. Therapeutic drug monitoring 2005, 27:451-456. Shah J, Wesnes KA, Kovelesky RA, Henney III HR: Effects of food on the single-dose pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of tizanidine capsules and tablets in healthy volunteers. Clinical therapeutics 2006, 28:1308-1317. Gidal BE, Maly MM, Kowalski JW, Rutecki PA, Pitterle ME, Cook DE: Gabapentin absorption: effect of mixing with foods of varying macronutrient composition. The Annals of pharmacotherapy 1998, 32:405-409. 16 Table 1: Circadian variation in pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, as well as, drug-food interaction of most commonly prescribed MS drugs Drug Food-drug interaction Baclofen No effect [46] Dantrolene No effect [47] Pregabalin Consuming with food decreased the Recommendation cmax by 25-30% and delay tmax by about 3h [48] Tizanidine Simultaneous food intake with Extent of absorption is increased up to 20% relative capsule reduced the cmax and the to administration of the capsule under fasted AUC o-t by less than 20% and conditions. extends tmax from 0.75 h to 1.5 h. In contrast Simultaneous food The tablet and capsule dosage forms are not consumption with tablet increased bioequivalent when administered with food. cmax and the AUC o-t by 22.6% and Food increases both the time to peak concentration 45.2% respectively [49] and the extent of absorption for both the tablet and capsule. However, maximal concentrations of tizanidine achieved when administered with food were increased by 30% for the tablet, but decreased by 20% for the capsule. Under fed conditions, the capsule is approximately 80% bioavailable relative to the tablet. Using tizaniidine together with caffeine is generally not recommended. Combining these medications may significantly increase the blood levels and effects of tizanidine. 17 Gabapentin High protein food increased AUC Take extended release tablet with evening meal. and cmax by 26% and 32% Swallow whole; do not chew, crush, or split. respectively [50] No significant effect on rate or extent of absorption of immediate release tablet Increases rate and extent of absorption of extended release tablet Carbamazepi Carbamazepine serum levels may be Extended release tablets should be administered with ne increased if taken with food and/or meals; swallow whole, do not crush or chew. grapefruit juice. SSRIs Paroxetine: Peak concentration is increased, but bioavailability is not significantly altered by food Sertraline: Average peak serum levels may be increased if taken with food. AUC o-t , area under curve from administration (0) to last observed concentration at (t), cmax, maximum concentration, tmax, the time after administration of a drug when the maximum plasma concentration is reached 18 Table 2: Effect of fasting on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of immunosuppressants and manufacturer’s recommendation for their consumption Drug circadian variation in manufacturer’s recommendation pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics Azathioprine Taking after meals or in divided doses for decreasing stomach upset Cyclophosphamide On an empty stomach with a glass of water or juice or with food Tablets are not scored and should not be cut or crushed. To minimize the risk of bladder irritation, do not administer tablets at bedtime. Methotrexate Methotrexate peak serum On empty stomach with plenty of water levels may be decreased if limit or avoid caffeine intake if you are taking taken with food. methotrexate. Avoid drinks, foods, or diet pills that Milk-rich foods may decrease contain caffeine, such as coffee, tea, cola, and methotrexate absorption. chocolate. 19