Q - Year9Hist

advertisement

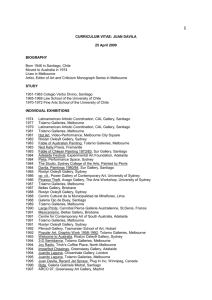

Living and working conditions in Australia at the turn of the twentieth century The urban experience The influx of immigrants due to the gold rushes of the 1850s led to the rapid development of cities such as Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. By 1888, Melbourne had grown to become the largest city in Australia and the second largest in the entire British Empire. Housing booms in Sydney and Melbourne in the 1880s led to the creation of new outer suburbs connected by road, rail and tramway. At the close of the nineteenth century, almost two-thirds of Australia's 3.76 million people lived in urban centres. New opportunities The long boom that lasted from the 1850s to the 1890s saw Australian workers become among the best paid and least overworked in the world. A labour shortage throughout Australia, however, meant that employers were forced to offer high wages and better working conditions to attract skilled workers. These were essential for the creation of new public buildings, roads, railways, ports and housing. The growth of the wool, mining and manufacturing industries also meant that thousands of additional workers were required. The labour shortage meant that workers had the luxury of choosing the employer that paid the highest wages. Australian male workers had an average life expectancy of 47 years—this was four years longer than male workers in Britain. It was during this period that Australia earned a reputation as a working man's paradise. Leisure and entertainment After the introduction of the eight-hour day in 1856 and its gradual extension to most workers across Australia, more and more workers gradually found themselves with time on their hands. People made the most of this by attending public carnivals and celebrations, picnics and sporting events. With the working day over by 1 p.m. on Saturday, spectator sports such as football, cricket and horseracing became even more popular. In 1888, over 100 000 people watched the running of the Melbourne Cup. Nowhere in my travels have I encountered a festival of the people that has such a magnetic appeal to a whole nation. The (Melbourne) Cup astonishes me! Source 6.1 American author Mark Twain after his attendance at the 1888 Melbourne Cup Living conditions Poverty was a daily reality for many unskilled workers. Inner-city areas within walking distance of the factory or workplace were overcrowded and unhygienic. High rents often forced several families to cram together inside hastily built slums. These conditions provided a breeding ground for carriers of disease such as rats and fleas. Industries such as tanning, which produced animal wastes, were kept well away from the more affluent outer suburbs. Densely populated working districts by the water were therefore often characterised by offensive smells and piles of rotting garbage. Toilets were usually nothing more than a tin bucket located in the backyard 'dunny' or shed. Behind each backyard ran an alleyway just large enough for the nightman's horse and cart. It was the nightman's job to collect the sewage from each house and dispose of it in the nearest waterway. Public health problems In 1900, Sydney experienced an outbreak of bubonic plague. This had been caused by a serious rat problem throughout the city. Sufferers of the plague developed a high fever and pus-filled buboes in their armpits. In response, health authorities ordered the houses of sufferers to be fumigated and disinfected. Squads of rat-catchers were employed to trap, kill and burn as many rats as possible. By the turn of the century, better knowledge about infectious diseases led to the improvement of isolation facilities such as the Quarantine Station on Sydney's North Head. Here patients could be treated while being kept away from the rest of the population. Overall, it is estimated that around 500 people throughout Australia died of the bubonic plague at the beginning of the twentieth century. Inner-city crime By 1890, the populations of Sydney and Melbourne had more than quadrupled in thirty years. Such unplanned growth led to overcrowding, particularly in inner-city areas close to factories. These areas tended to attract lots of young working-class men, many of whom had come from the country in search of work during good economic times. Called larrikins, these young men were known for their antisocial behaviour, which offended the members of the wealthier middle class. Groups of larrikins could typically be found on street corners where they would drink, swear, play gambling games such as 'two-up' and occasionally brawl. Chinese people were often the targets of their insults and violence. Although far fewer in number, young women who associated with larrikins were called 'larrikinesses'. While larrikins were generally more of a nuisance than a genuine threat to most citizens, some formed their own criminal gangs. These gangs were called pushes and took on names such as the 'Rocks Push', the 'Forty Thieves' (from Surry Hills, Sydney), the 'Little Lonsdale Street Push' (from Melbourne) and the 'West Adelaide Push'. Pushes controlled their own patch of territory, which was usually a particular street or block. These areas often became unsafe areas for more respectable families. Gang members would use their tools of trade, such as hammers, knives and iron bars, as weapons. Australia's first ethnic gang was the 'Tipperary Boys', a group of Irish Catholics from Melbourne who terrorised Protestant politicians and threatened to burn Melbourne down when their preferred candidate was defeated in local elections. He generally follows his calling between the ages of 11 and 19. He is vulgar, mean, rude, abusive, cruel, sneaking, dishonest, cunning and an abject coward … When assembled together larrikins insult, ill-treat and abuse all those who are weaker in number or in physical strength than themselves … Surely a good sound flogging [is needed on] such a very offensive animal. Source 6.5 Editorial about the larrikin problem in the Adelaide Advertiser,1 March 1876 Life for the wealthy Those from the richest families in the colonies inherited their wealth and didn't have to work at all. Most members of the upper middle class were able to obtain a university education. Males typically entered the professions as doctors, lawyers and engineers, while the few women who wanted to work trained as teachers and nurses. A medical specialist in 1900 could earn over £10 000 a year, while a family doctor could earn up to £1000 a year. The lower middle classes were white-collar workers—clerical and office workers—which required skills in accounting, administration and business. Such skills ensured that they received a much higher income than unskilled labourers. As a result, they could afford bigger houses on the outer fringes of the city, where life was quieter and conditions better. Greater wealth meant that the middle class could afford to go to the theatre or opera. Working conditions By the end of the century, Australia had earned a reputation as an egalitarian society free from the class distinctions of the Old World. Reforms such as the eight-hour day, however, were available only to skilled workers belonging to trade unions. For those able to obtain trade union membership—typically men of Anglo-Celtic background—Australia was a working man's paradise. They worked fewer hours, received more pay and enjoyed more rights than workers anywhere else in the world. Nevertheless, conditions in factories were very poor by today's standards. These were often poorly ventilated and stifling in the heat of a summer. Unskilled workers could work for up to 48 hours a week for wages as low as £1 a week, with no extra pay for overtime. Qualified tradesmen earned up to £3 a week. The Australian workman has substantial reason for glorying in the fact that while working fewer hours per week than is the rule in the old world, he nevertheless has more money at his disposal, and is able to secure for himself and those belonging to him a larger share of the good things in life. Source 6.7 Adelaide Advertiser, 1902 Q Identify three reasons why Australian workers were said to be better off than workers in the 'Old World'? For the majority of non-union workers, Australia was far from a paradise. Women, children, nonEuropean immigrants and Aboriginal People continued to work long hours and were paid at rates well below the trade union award, or minimum industry rate. Many such workers did not have the protection of a union and were forced onto individual contracts that strongly favoured the employer. Unskilled workers tended to be paid by piece-rate. This also advantaged the employer since it meant that a worker went unpaid when demand was low. Unskilled workers had to look for other employment at such times, making rent payments almost impossible to meet. From boom to bust The good times brought about by the gold rushes could not last forever and by 1891, the onset of an economic depression brought the 'boom years' to an abrupt end. Widespread business closures meant that work was suddenly much harder to find. As wages decreased and shortages led to price increases, many workers decided to escape the poverty of the city by 'going bush' in search of work. … if Australia at present presents the Working Man's Paradise, I should hardly care for a glimpse even of the Working Man's Hades [hell]. Source 6.8 From Workingmen's Homes, by Matilda Emilie Bertha McNamara, who ran a homeless shelter in Sydney, 1894 Q 1 What is Bertha McNamara's view of Australian working conditions? 2 How might her experience have helped form this view? Women's experience In a male-dominated society in which women tended to remain in the private sphere, sexist attitudes were widely accepted. Most women were considered dependants—that is, earning no income of their own—of their fathers or husbands. The few women who worked tended to be young and single, as married women were expected to raise children and take care of the family. The main form of work for a young woman was domestic service, which meant being a housemaid, a cook or a nanny for wealthier families. Educated middle-class women usually became teachers or nurses. Q 1 What do you suppose the approximate age of this girl is? 2 What were her alternatives to working as a domestic servant?