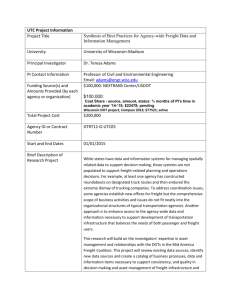

Could the DCFR be an answer to the lack of harmonization in the

advertisement

Could the DCFR be an answer to the lack of harmonization in the field of forwarding law? Part I – Legal qualification Dr. Anastasiya Kozubovskaya Pellé Introduction Who is the carrier in the line of sub-contractors involved in the carriage of goods by sea? Or let’s put it in other words: « who is liable to pay damages when the cargo is lost or damaged?» Will the freight forwarders shipping under its own bills of lading be held liable and in what capacity? This is a major and classic question that faces cargo owner. Although the law of carriage of goods is to a large extent harmonized by several international conventions 1 the attempts to harmonize the law of freight forwarding on international level have failed 2 . Consequently, the freight forwarders (legal qualification and liability) are still governed by national laws and therefore attract forum shopping attitude and uncertainty into the contractual relationship. The Principles, Definitions and Model Rules of European Private Law, Draft Common Frame of Reference (DCFR) and Principles of European Contract Law (PECL) have been elaborated with the aim of providing European internal market with a uniform contract law. Various international and regional organisations, recognising that diverging contract law rules create obstacles to international trade, have been working to reduce such obstacles by providing uniform model rules. Although the DCFR and PECL do not deal with contract of carriage3 and do not refer to the freight forwarding4, it contains some basic general principles, notably on contract interpretation and agency, that could be applied to a certain extent to the freight forwarding activity. However, the carriage of goods is victim of its success, as the existence of several international conventions (Hamburg Rules, Hague Rules, Hague-Visby Rules, Rotterdam Rules) prejudice the benefits of the said harmonization. 2 The UNIDROIT Draft Convention on Contract of Agency for Forwarding Agents relating to International Carriage of Goods was never submitted to a diplomatic conference. 3 The DCFR refer to it only in the light of the contract of sale which involves carriage of the goods and with a sole purpose to specify obligations of the parties to the contract of sale And the article 102 (Book II, Part C) of the Chapter II Rules applying to Service contracts in general clearly specifies that this part does not apply to contracts in so far as they are for transport. 4 What could be easily understood bearing in mind different attempts in the past to harmonise the law governing freight forwarding. Jan Ramberg, "Unification of the Law of International Freight Forwarding", RDU 1998-1, p. 5. 1 From legal qualification of a freight forwarder – intermediary or principal – will depend the liability he will be subject to. Legal qualification of the freight forwarder’s function will usually vacillate between two contracts: agency or carriage of goods, and therefore between two legal qualifications: agent and carrier. Whether the freight forwarder is an agent or a principal contractor depends on the facts of each case and on the law of the jurisdiction the case is brought to. Professor Tetley points out in this respect that « there are no hard rules for determining whether the freight forwarder is acting as agent or as principal contractor. The forwarder’s role will depend on the facts of each case. There are, however, several useful criteria which can assist in making that determination »5. To make it more complex, in a midway between the principle and contractor the French law places commissionaire de transport– agent with a specific legal regime. The freight forwarder may act as: 1) performing carrier - when he executes the carriage of goods; 2) contracting carrier - although he does not execute the carriage of goods he assumes the liability and the legal capacity of the carrier (contractual carrier and transporteur apparent); 3) agent on behalf of the performing carrier. The main difficulties related to the legal qualification of the freight forwarder appear most frequently with regard to the last two situations. We will first analyse the situation when the freight forwarder’s activity is qualified as agency (I. Freight forwarder as an agent), and then examine the possibility of qualifying it as a carrier (II. Freight forwarder as a carrier). When conducting this analysis we will search for the provisions of the DCFR that might be applicable to the respective situations. Part I. Freight forwarder as an agent Originally the freight forwarders were regarded as agents and the terminology used to define them was "freight forwarding agent". The problem occurs because of lack of uniform "agency" law. In the French law, there are two kind of "agents": commissionnaire de transport and mandataire. The main difference for the legal qualification between them is that although both act on behalf of the principal, the CT acts in his own name and the M acts in the name of the principal. The CT, in midway between the principle contractor and agent (mandataire), is unknown in Common law countries. If a parallel to be done, the CT would be closer to the undisclosed agency (the existence of the principal is not revealed by the agent to a third party), although the M would be a kind of disclosed agency (the existence or the name of the principal is revealed to the third party by the 5 Tetely W., Chapter 33, Marine Cargo Claims, 4th ed., 2008. agent). French law CT is sometimes presented by English doctrine comparing him to the English law agent as "indirect agent"6. In the case of disclosed agency, the agent himself is not normally entitled to the benefit of, or be liable on, the contract. In undisclosed agency the agent is also entitled and liable on the contract (ibid). Where under Common law a freight forwarder would be legally qualified as a principal contractor, i.e. a carrier, under French law he could still be qualified either as a carrier or as CT. Although if under Common law freight forwarder is qualified as an agent, under French law the discussion will take place to know if he is a CT or M. The legal qualification of an operator (CT or M) became a classic discussion in the transport hearings in the French courts. The operator's advocate will try to convince the judge that his client was acting merely as a mandataire although the shipper's (or cargo owner's) advocate will make his best to show that the operator acted in capacity of commissionnaire de transport or in capacity of a carrier. To resume, whether the freight forwarder is acting as an agent (CT or M) or as a principal contractor (carrier) depends on the facts of each case and on the law of particular jurisdiction in question7. A proliferation of forum shopping attitude in the shipping claims is a consequence of this situation. Regarding agency, the DCFR contains two chapters devoted to Representation (Book II, Part C, Chapter II) and Mandate contracts (Book IV, Part D). According to the article IV. D. – 1:101 of the DCFR, the provisions related to the mandate apply "where the agent undertakes to act on behalf of, and in accordance with the instructions of the principal". They apply to contracts and other juridical acts under which a person, the agent, is authorised and instructed (mandated) by another person, the principal: (a) to conclude a contract between the principal and a third party or otherwise directly affect the legal position of the principal in relation to a third party; (b) to conclude a contract with a third party, or do another juridical act in relation to a third party, on behalf of the principal but in such a way that the agent and not the principal is a party to the contract or other juridical act. To make a parallel with French "agency" law, the first situation (described in (a)) would correspond to the French mandate contract, although the second one (described in (b)) would correspond to CT contract. The DCFR go further and explicitly lay down provisions with regard to the direct and indirect representation. According to the article IV. D. – 1:102 of the DCFR, Chuan J., "Law of International Trade", 3rd Edition, London, 2005, p. 51-75. « Agent : a person appointed by another (the principal) to act on his behalf, often to negotiate a contract between the principl and third party », Dictionnary of Law, 6th Edition, 2006, by E. A. Martin, J. Law, Oxford, P.23. 7 Tetely W., Chapter 33, Marine Cargo Claims, 4th ed., 2008. 6 (d) a mandate for direct representation is a mandate under which the agent is to act in the name of the principal, or otherwise in such a way as to indicate an intention to affect the principal’s legal position; (e) a mandate for indirect representation is a mandate under which the agent is to act in the agent’s own name or otherwise in such a way as not to indicate an intention to affect the principal’s legal position. The mandate rules laid down by the DCFR could be applicable in the shipping. They would apply only to the relationship between the principal (carrier) and the agent (freight forwarder), i.e. mandate relationship, and would not apply to the relationship between the principal (carrier) and the third party (shipper) or the relationship (if any) between the agent (freight forwarder) and the third party (shipper). As they clearly lay down the obligations of each party, they will contribute in the European internal market to an uniform interpretation of the contractual relationship between these two parties. As the DCFR clearly define direct and indirect representation, these rules will contribute avoiding divergent interpretation by different jurisdictions with regard to the parties to the prospective contract (principal or agent). As we have already mentioned before the denial of the existence of indirect representation (and therefore denial of being personally liable to the third party by virtue of the contract concluded on behalf of the principal) is frequent defence of the freight forwarders (CT) in the French courts. …. Part II. Freight forwarder as a carrier The freight forwarder will be qualified as a carrier when: 1) he performs the carriage (performing carrier); 2) even though he does not execute the carriage of goods, he assumes the liability and the legal capacity of the carrier. We will call him "contractual carrier" in contrast to performing carrier. Here we will distinguish two different situations: 2.1. when a freight forwarder expressly agreed to act as principal, thus subjecting him to carrier liability (express contractual intent) 2.2. when there was only an implied agreement following from the freight forwarder’s statements or conduct. In the French courts it is not unusual to see the freight forwarder being held liable as a carrier - transporteur apparent – for the reason that he appeared in the eyes of the shipper as a carrier because of his conduct and the documents issued. American law provides an example of freight forwarder in the capacity of contractual carrier: the Non-Vessel-Operating Common Carriers (NVOCC). "The NVOCC acts in dual capacity: as a common carrier in relation to its shipper, and as a shipper (agent of the cargo owner) in relation to the underlying carriers". The NVOCC is described by the Ninth Circuit as "intermediary between the shipper of goods and the operator of the vessel that will carry the goods"8. Under the French law the freight forwarder acting as NVOCC is most likely to be qualified as CT. In certain cases, he could be qualified as transporteur apparent if the documents he issued and the way he behaved himself made the shipper in good faith believing that he was dealing with a carrier and not with an intermediary9. ….. Conclusion Although the DCFR do not apply to the transport contract, neither directly to the freight forwarding activity, the latter is concerned in so far the provisions addressing representation and mandate contracts could be applicable to freight forwarder and the principle. Moreover, the DCFR general provisions on formation, validity, interpretation of the contracts, performance of obligations and on the remedies for the non-performance could be applicable to a certain extent to this relationship. "The DCFR may furnish the notion of a European private law with a new foundation which increases mutual understanding and promotes collective deliberation on private law in Europe"10. The DCFR could be also a possible source of inspiration in the harmonization and modernisation process of national legislations. "The PECL, which the DCFR incorporates in a partly revised form, received the attention of many higher courts in Europe and numerous official bodies charged with preparing the modernisation of the relevant national law of contract. [...] If the content of the DCFR is convincing, it may contribute to a harmonious and informal Europeanisation of private law"11. … Tetley W., Chapter 33, Marine Cargo Claims, 4th Edition. Kozubovskaya Pellé A., "De la qualité juridique de transporteur maritime de marchandises: notion et identification", PUAM 2011, p.160; Morinière J.-M., "....". 10 Comments to the DCFR, January 2009, Christian von Bar, Hugh Beale, Eric Clive, Hans Schulte-Nolke, § 7. 11 Ibid, § 8. 8 9